Heritage Algorithms and Other Letters to the Future

Stephanie Comilang & Simon Speiser, Piña, Why is the Sky Blue?, 2021, video/virtual-reality installation, color, sound, video still. [courtesy of the artists and Julia Stoschek Foundation, Berlin

Share:

Over twenty years ago, the exhibition The Quilts of Gee’s Bend opened at the Whitney Museum of American Art. The quilts from the “women of the Bend” presented complex improvisational patterns and a mixture of found fabric and textures. In his New York Times review, Michael Kimmerman delivers this robust description of the material and techniques used:

The women of the Bend have passed down an indigenous style of quilting geometric patterns out of old britches, cornmeal sacks, Sears corduroy swatches and hand-me-down leisure suits—whatever happened to be around, which was never much. Quilts made of worn dungarees sometimes became the only mementos of a dead husband who had nothing else to leave behind. They provided comfort and warmth, piled on top of corn shuck mattresses or layered six or seven deep for the cold nights.1.

Many of the quilters used a railroad stitch, a pattern in which interlocked threads create“tracks” and embedded in these tracks is the evidence of life—stories and songs, memories and secrets.

The Quilts Of Gee’s Bend, installation view, 2002, [ photo: Jerry L. Thompson; courtesy of Whitney Museum of American Art, New York]

The passage of time since the exhibition encompasses two decades rife with global polarization, fascist dictatorship, and a pandemic that has exposed the racial violence rampant in public health industries. Crucial to this time is the advancement of the internet as resource and world builder. In 2002 an analogue lifestyle was still imaginable; a digital multiverse remained optional. Today, seeing a doctor requires a digital footprint, an advancement that disenfranchises many, and coincides with a time when the internet serves as a refuge for the margins, a third space.2 The quilt, endowed with intricate patterns, is meant to nurture loved ones and kin, and it poses a similar duality as does the internet, where immediate connection and convenience are traced by an algorithm. To align the quilt to the algorithm recognizes the Gee’s Bend quilters’ investment in our collective future.

The Quilts Of Gee’s Bend, installation view, 2002, [ photo: Jerry L. Thompson; courtesy of Whitney Museum of American Art, New York]

Twenty years later, new media artist and director of NEW INC. Salome Asega joined Legacy Russell—executive director and chief curator at The Kitchen, and curator of The New Bend—to present an exhibition inspired by the Gee’s Bend quilters’ vision and in service of their praxis. Russell asserts, “There is a different kind of listening that is required to both view the works and to hear them.” Seeded in the groundwork laid by the Gee’s Bend quilters, The New Bend aims to elevate a pathway for such “listening” in a multidisciplinary overview including such artists as Genesis Jerez, Diedrick Brackens, and Eric Mack. Russell’s imperative implies a sensorial experience rarely introduced to frameworks for engagement in the art world. The typical system of values often relies upon formal standards of inquiry and canonical reference rooted in Eurocentrism—to say nothing of personal intuition. The materiality on display in The New Bend, without focusing too long upon the works’ aesthetic value, is often referred to by Russell and Asega as “data,” which suggests a computational dimension to the work. To consider these quilts as harbingers of data insists on their encryption, or the story of the thread, as a critical means for making and looking. More recently, in 2018, the New York Times created a documentary featuring interviews with some of the Gee’s Bend quilters. It includes a brief clip showing a few small squares of notebook paper, arranged in a quilter’s lap. She appears to use those square paper swatches to organize the composition of the quilt in progress. According to design scholar and professor Audrey G. Bennett, this method demonstrates to students of color that “computational thinking or the thinking behind the creation of computer algorithms [shows] how these concepts can appear in Black youth’s everyday lives.”3 Bennett, who co-wrote “On Cultural Cyborgs” with professor and design scholar Ron Eglash, describes these methods as “heritage algorithms,” which commemorates strategic design while also elevating its usage. Bennett considers heritage algorithms to be “computing concepts inherent to indigenous practices.”4 This naming grants authority to legacies of Black and Indigenous quilting and basket-weaving practices, and it amplifies future relationality, both interpersonally and between generations. Here, materiality constitutes the promise of a future, beyond the looming threat of white supremacist or misogynist encroachment or violence. These techniques presents computational strategies to be built upon or, as Russell noted in her conversation with Asega, “letters to the future.”5

“The New Bend”, Installation View, 2023, [Photo: Ken Adlard; courtesy of the artists and Hauser and Wirth, New York]

When I first noted the title of Kimmerman’s New York Times review—“Jazzy Geometry, Cool Quilters”—I found use of the word cool off-putting, mainly for its nonspecific and somewhat limiting scope. The word geometry, however, lands with more clarity. Kimmerman seems to have been searching for an embedded sense, a code—perhaps a word that would indicate composition. Another word that aligns with this concept is felt. I situate my conceptualization of felt within its initial meaning—the past tense of feeling. Felt, the densely matted material; and felt, an emotion stored, a previousness, touch upon the second part of Russell’s endeavor to hear differently. In her foundational text Therapeutic Nations: Healing in the Age of Indigenous Human Rights, indigenous feminist scholar Dian Million encourages hearing as a form of matrilineal witnessing. Million describes this approach as “felt theory,” a concept within the longstanding feminist legacy of first-person narratives by women. Million states, “Indian and Métis women participated in creating new language for communities to address the real multilayered facets of their histories and concerns by insisting on the inclusion of our lived experience, rich with emotional knowledge, of what pain and grief and hope meant or mean now in our pasts and futures.” Meant or mean now. Use of the word felt in “felt theory” delivers the multivalent meaning purposefully. The repeated reinforcement engenders storied vision as if through a textual language, much like the quilt. Million clarifies this feminist praxis by arguing for “felt experience as community knowledge.” One such example occurs in The Spruce Root Basket (2016)—by Jennie Wheeler (Tlingit), from Yukutat, AK—calls for the requirements of “felt experience and community knowledge” to source the materials, patience for their adequate preparation, and wisdom to retain the intricate weaving process. “The weaver treats the materials with care and invests harmonious creative energy in them. Weavers often note the importance of coming to weaving with a positive mind, as this energy is thought to transfer into a completed work.”6

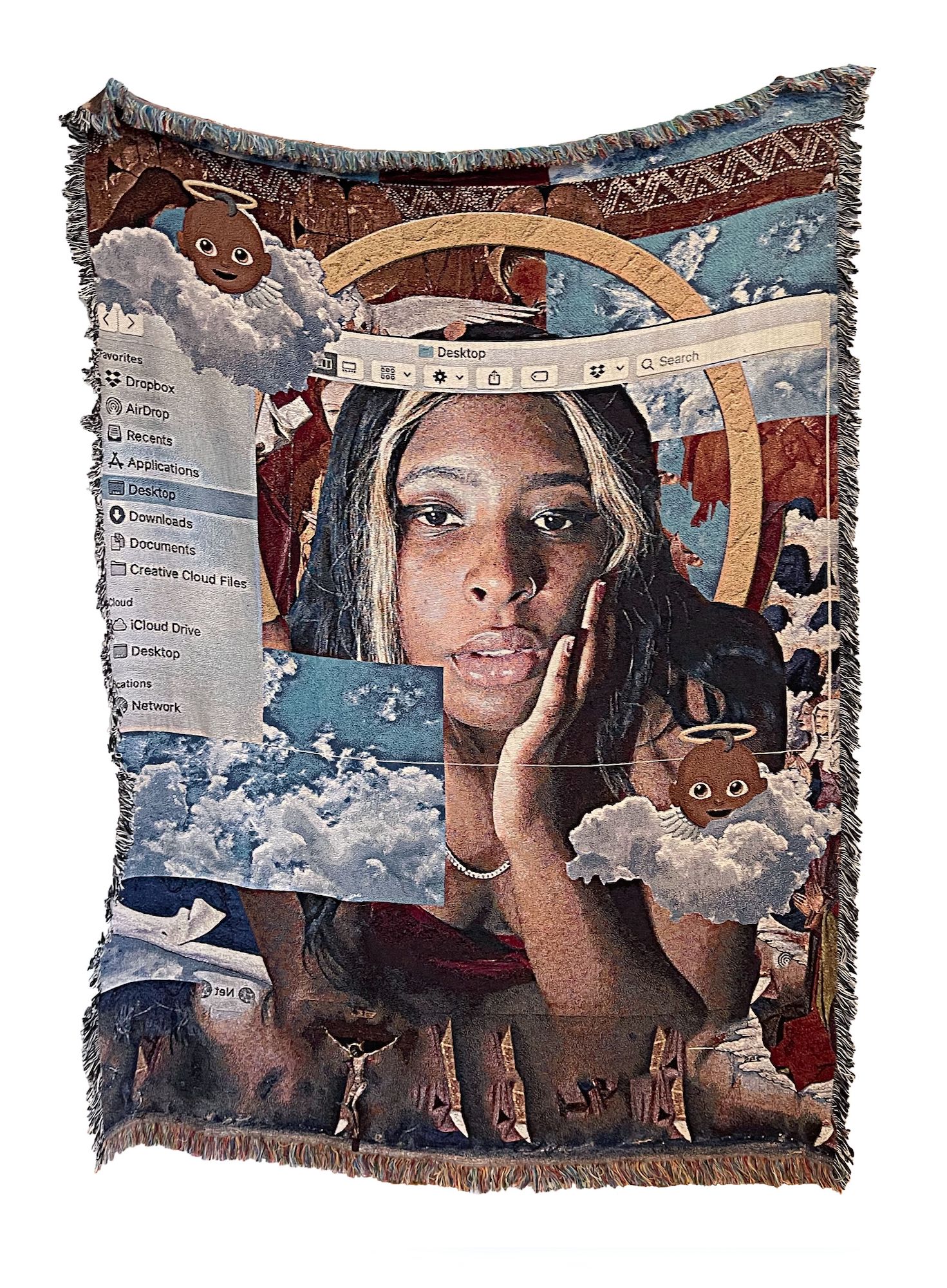

Qualeasha Wood, Ctrl+Alt+Del, 2021, Cotton Jacquard weave, glass beads, 84 x 62 x ½ inches [photo: Qualeasha Wood; courtesy of the artist and Gallery Kendra Jayne Patrick, New York]

Indigenous intersectional feminist scholarship aligns with Black feminist tradition. The Combahee River Collective, for example, considered emotional wellness to be a categorical and intersectional framework. Collective members write, in a statement, “We have spent a great deal of energy delving into the cultural and experiential nature of our oppression out of necessity because none of these matters has ever been looked at before. No one before has ever examined the multilayered texture of Black women’s lives.”7 One of the Gee’s Bend quilters described the process of making as “a way to occupy my hands.” It is within this steadfast tradition of resiliency that the knowledge shared between women across kitchen tables or at quilting circles pulses through the threads—felted, matted, composed. The thread, or the story of the thread, might never be contained inside the museum. It is through the embodiment, the ways we have come to show our work, display our findings and their origins, that we invite legacy. The multidisciplinary exploration of fastidious heritage algorithms found within Gee’s Bend quilts in Hauser and Wirth’s 2022 exhibition The New Bend explores this lineage on the basis of function. Many reviews of the exhibition express confusion regarding the mélange of visual art, collage, and textiles, rather than quilts alone. Decolonizing one’s point of view requires much more than representational or aesthetic reframing. Russell’s curatorial approach further illustrates the generative—as opposed to extractive—essence of heritage algorithms as life-giving approaches to making, looking, listening. The New Bend celebrates relationality and reciprocity, emphasizing Bennett and Eglash central tenets—“not reducing culture to code but expanding coding to embrace culture.”8

Ctrl+Alt+Del (2021), a work by Quaeleasha Wood, thrillingly displays this dynamic with a digital pattern against a jacquard weaving of a selfie, adorned with emojis and a computer drop down menu. Here, the selfie takes on the rubric of portraiture with the distressed expression of the figure, archiving a contemporary image through a historical process. Another artist who works with quilting is Basil Kincaid, whose Four Eyes One Vision (2021) combines Ghanaian wax block fabrics, lace, and hand-woven Ashanti kente. Diedrick Brackens makes one of the most dazzling and moving contributions to yarn and weaving practices in recent years with survival is a shrine, not a small space near the limit of life (2021). Against rich cobalt, a figure crouches with arms lifted in exaltation—the silhouette’s edges soft, threads dangling and reachable. In Forward walking boy on the edge where the sand meets the shore (from DES HOMMES ET DES DIEUX) (2018)—a banner-like work that use organza and cotton handkerchiefs—Eric Mack presents something more playful and atmospheric.

Jubilee (2021) by Anthony Akinbola delivers this theme of critical context as canon at every point. Akinbola’s clever, luminous layers of Durags invoke works by Senga Nengudi, who used hosiery to expand on dimensionality (or, similarly, Mark Bradford’s use of end papers), an association that is aided by the viewer’s perspective—gazing upward reveals a subtle change of shape and tone in the work. Mixed media painters Genesis Jerez and Sojourner Truth Parsons work in parallel lanes through the textured domestic scene in Jerez’s Blue Ballerina (2021) and Parsons’ neon acrylic on canvas and linen, red goes away (2021). The works in The New Bend all touch upon diasporic longing—a nostalgia for an unexperienced past that is potentially in conflict with the formulation of a self that is positioned in the future.

“The New Bend”, Installation View, 2023, [Photo: Ken Adlard; courtesy of the artists and Hauser and Wirth, New York]

Diasporic longing as critical context is profoundly interrogated in the 2022 exhibition—a collaboration between Stephanie Comilang and Simon Speiser—Piña, Why is the Sky Blue?. The exhibition centers upon Piña, an oracle and omniscient presence from the future, who receives and sends transmissions in the forms of questions and images. The film opens to a lush meadow on a sun filled day with a pineapple-shaped tower in the distance. Piña communicates with three different communities, or domains, and viewers experience Piña’s transmissions through a film accessed by using virtual reality technology. Piña’s poetic dispatches flow in as the camera pulls the pineapple tower more into focus:

I have been made again.

I am here for you.

Made out of all of you.

Made out of your lost world.9

Interspliced are scenes of what appear to be abandoned buildings, one which bears the signage “BIBLIOTECA VIRTUAL.” We find ourselves in a future domain, whence Piña communicates with the past and the future. Eventually the point of view lingers on a single sprout from a small pond, surrounded by rocks, and Piña describes her origin story:

I was swallowed, I think.

Swallowed by the thing

That swallowed everything.

And then I just floated for a while

Floated up and down what felt like

The calmest ocean

And in this ocean

I was collecting the debris of all that remained,

and all that could get to me

It wasn’t much but

the things that were transmitted were important.

It was life.

It gave me life.10

Dispatches are received by Kankwana Canelos and Rupay Gualinga, who are a part of an Indigenous activist collective, Ciber Amazonas, which transmits radio broadcasts with resources and stories, and which resists patriarchal land acquisitions through radio broadcasts intent upon reaching women in the Puyo, Ecuador community. Janet Dolera is a Babaylan in Pulawan, Philippines, who connects with her community through healing care work called hilot. Ecuadorian elder Alba Pavon shares her knowledge of the land with her community through oration and song, as in griot tradition. As Piña continues to send messages, they begin to physically appear in the landscape, floating in the water, leaning on the rocks. Communicating within these networks has kept the oracle alive. The exhibition debuted at Gallery TWP, an artist-run center in Toronto in fall 2022. The exhibition’s curator Heather Canlas Riggs states, “Through Piña, Comilang and Speiser envision a future where accessing and safeguarding such embodied pre-colonial knowledge is facilitated by connecting with an empathetic technologic spiritual entity.”11 Piña, Why Is the Sky Blue? uses VR to explore communication between ancestors and future selves.

Stephanie Comilang & Simon Speiser, Piña, Why is the Sky Blue?, installation view, 2021 [photo: Alwin Lay; courtesy of the artists and Julia Stoschek Foundation, Berlin]

The internet has reshaped our definitions of convenience, comprehension, and knowledge sharing. Wisdom often feels scarce, or even unsatisfactory, given the limited range for our yearning, let alone our fleeting attention spans. Despite this sense of diminishment, wisdom will never be obsolete, especially when we can recognize the embodied modes of knowledge sharing and genre building yet to unfold. Materiality carries ancestral wisdom that reaches far beyond the capacity of emerging technologies.

Piña, Why is the Sky Blue? presents viewers with a contemporary fiction to address the essence of heritage algorithms—“computational concepts inherent to indigenous practices.” The Ciber Amazonas use analogue technologies as education portals to sustain community resources. The oracle represents the quilt, an embodiment of the algorithms sending transmissions as signs of life and continuation beyond. “I am still here” is a momentous call, gently initiating a vigilance that spans previous and future generations of care. The instinct to create refuge on the internet—be it via Tumblr or, more recently, TikTok and other communities of our own making—has always had computational history. Much like heritage algorithms, other frameworks of technological engagement must prioritize to whom these origins can be traced.

Stephanie Comilang & Simon Speiser, Piña, Why is the Sky Blue?, 2021, video/virtual-reality installation, color, sound, video still. [courtesy of the artists and Julia Stoschek Foundation, Berlin

Just two years before The Quilts of Gee’s Bend at the Whitney in 2002, I moved to New York to begin my undergraduate degree. In addition to extra notebooks, tubes of toothpaste, and packages of ramen noodles, my mother gave me a quilt. It was not a quilt she made, or even one that she’d had made for me. And there wasn’t much of story to accompany the quilt. When she gave it to me, she didn’t wrap it in a package or enclose it as a gift. Instead, she unfolded it and spread it across the small twin bed in my dorm room. She smoothed the edges and tucked the corners. This quilt marked a threshold, a passageway into a different realm of personhood—an independence nurtured by tradition and sanctuary. With this gesture, my mother endowed my future self, one she would never witness as a physical body, only as spirit. When I wrap the quilt around me now, I feel warm knowing the comfort my mother felt in bringing ease to my future.

Erica N. Cardwell is a writer and educator currently based in Toronto. She is the recipient of a 2021 Andy Warhol Foundation Arts Writers Grant in support of her first book, Wrong is Not My Name: Notes on (Black) Art. Her writing has appeared in ARTS.BLACK, Artsy, Art in America, frieze, BOMB, The Believer, The Brooklyn Rail, C Magazine, Studio Magazine, and other publications. Most recently, her writing is included in the anthology Track Changes: A Handbook for Art Criticism. Wrong is Not My Name: Notes on (Black) Art will be published by The Feminist Press in March 2024.

References

| ↑1 | Michael Kimmerman, “Jazz Geometry, Cool Quilters,” review ofThe Quilts of Gee’s Bend, at Whitney Museum, New York Times, November 29, 2002. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Licona, Andrea. “(B)orderlands’ Rhetorics and Representations: The Transformative Potential of Feminist Third Space and Zines” |

| ↑3, ↑4 | “Audrey Bennet on facilitating understanding of and diversity within STEM as cultural expression.” University of Michigan, Stamps School of Art and Design, YouTube. |

| ↑5 | In Conversation: Legacy Russell and Salome Asega, YouTube. |

| ↑6 | “Art as a Container for Culture.” Jackinsky-Sethi, Nadia. Hearts of Our People: Native Women Artists |

| ↑7 | The Combahee River Collective Statement |

| ↑8 | Heritage Algorithms Talk – Ron Eglash |

| ↑9 | Video, Piña: Why is the Sky Blue? Comiliang, Stephanie, Spieser, Stephen. |

| ↑10 | Canlas Riggs, Heather. Piña: Why is the Sky Blue? exhibition booklet, Gallery TPW |

| ↑11 | Canlas Riggs, Heather. Piña: Why is the Sky Blue? exhibition booklet, Gallery TPW |