Great Force

Alexandra Bell, Charlottesville, installation view [photo: Pomona College; courtesy of the artist and Pomona College, California]

Share:

The press preview was wrapping up. Journalists, community organizers, and artists were assembled at the Institute for Contemporary Art (ICA) at Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond, VA. Assistant Curator Amber Esseiva had just completed a tour of Great Force, her first solo-curated exhibition, and the final question from the gaggle of media came from another artist: “What do you think will make this show a success?” Esseiva responded quickly and with confidence, “I think it’ll be a success if it provokes conversation.”

Conversation is the heart of Great Force. The show features 24 contemporary artists exploring black-white inequality in the United States. The exhibition engages the audience in a variety of conversations between past and present, seen and unseen, personal and universal, expectation and reality.

Yet, unlike the familiar conversations about race in Richmond, former capital of the Confederacy, the dialogue created by Great Force is subtle, nuanced, and carried out in hushed tones and through thoughtful reflections.

Its purposeful curation unfolds in quiet phases. The conversations begin between the viewer and American writer and thinker James Baldwin, from whose words the exhibition draws its title: “The great force of history comes from the fact that we carry it within us, are unconsciously controlled by it in many ways, and history is literally present in all that we do.”

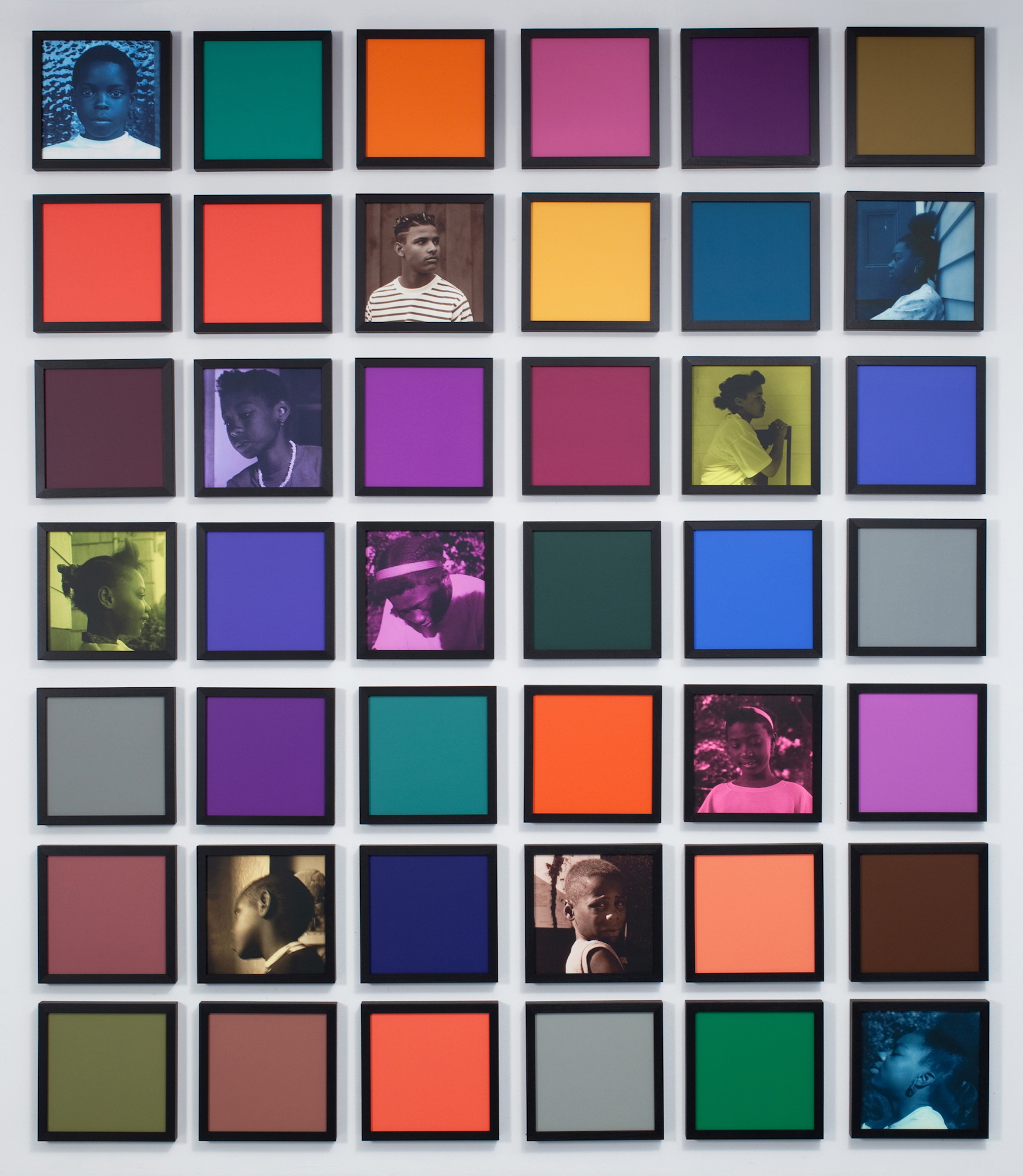

Carrie Mae Weems, Untitled, 2009-10, 42 inkjet prints, 90.25 x 77 inches [courtesy of the artist and Rodney M. Miller Collection]

History is a major theme, particularly for an exhibition at a contemporary art institute. The contradiction is intentional. “The concerns of the show have always been part of the American experience but are timely in new ways,” says ICA Executive Director Dominic Willsdon. Great Force opened in the 400th anniversary year of the first recorded enslaved Africans’ forced arrival onto North American shores. Although slavery sits comfortably in a space of “historical” importance, race remains a contemporary conversation, affecting the lives of all Americans, directly and indirectly.

As you enter the first gallery, a haunting voice—Marian Anderson’s—beckons. Sampled from a 1939 performance at the Lincoln Memorial, her ghostly voice is central to a work by Paul Stephen Benjamin, Let Freedom Ring (2017). This large installation displays several looped video fragments of the performance. The work refers to the singer’s triumph over a refusal to host her at Washington’s Constitution Hall. Anderson was barred by the Daughters of the American Revolution because she was black, but later she performed at the Lincoln Memorial before an audience of more than 75,000. Although Benjamin’s work is positioned farthest from the gallery’s entrance, it is the first you truly experience.

Anderson’s voice is in conversation with the entirety of the space, calling to you, from beyond your line of sight as you enter the gallery. Before you can discover the fullness of Benjamin’s work, you must pass beneath a sculptural arch just beyond the door of the exhibition space. That abstract architecture of giant octagons is, in fact, made of welded metal tables from prison visitation rooms. The work, swear it closed, closes it (2018), by Sable Elyse Smith, creates a welcoming construction fashioned from the furniture of imprisonment—a reference to the US prison system, which disproportionally imprisons more African Americans than it does any other race.

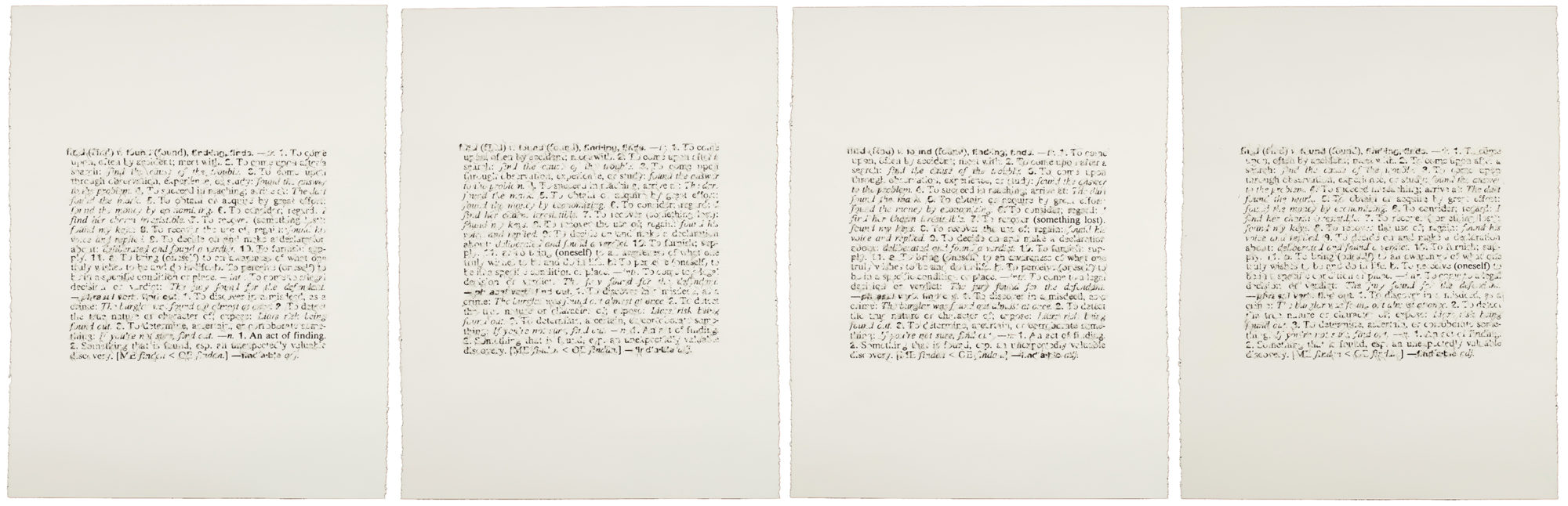

Bethany Collins, Find, 1982, 2016-17, American Masters paper, Black Magic erasers, dimensions variable [photo: James Prinz; courtesy of the artist and PATRON, Chicago]

Through this first abstract form begins the next major conversation, one that takes place between our expectations and the reality of this race-based exhibition. As you absorb the entirety of the gallery, you see no lynched bodies. You’re not assaulted by the sight of a Ku Klux Klan robe or a body in chains. Instead, you see works that merely hint at their relation to race—such as Slab III and Emerging Block (Building) by Kevin Beasley (2018). These structures of cotton, clothing, and resin stand seven feet tall. Warm and haunting, the works reference materials once harvested by enslaved hands, yet they never state that institution’s name explicitly.

As Anderson’s voice continues to pulse throughout the gallery, you are drawn to another work, this one by Xaviera Simmons. It consists of a multi-hour video showing the artist potting flowers; that video is flanked by two additional ones: on the left, a series of abstract white blocks piles up against a black background; on the right, facts about slavery loop on a screen. Simmons’ work is titled Capture (Say a butterfly had to die for you to get a gift—there must be some kind of prayer in that—I want to know how you feel about capture).

It is clear that, in her curatorial debut, Amber Esseiva asks us to consider race beyond the oversimplified battle between oppressed victim and hateful overseer. She asks us, instead, to work for the value contained in this out-of-date invention of black and white. As with any good conversation, we are required to participate. We must read the labels. We must reflect. We must consider how each work talks with its neighbor. And only then does the exhibition begin to unfold for us.

Kevin Beasley, Emerging Block (Building), 2018, polyurethane resin, raw Virginia cotton, housedresses, kaftas, t-shirts, altered housedresses, altered kaftans, altered t-shirts, 72 x 19.5 x 24 inches [photo: Jason Wyche; courtesy of the artist and Casey Kaplan, New York]

The second-floor galleries continue the conversation. There, we see a dialogue between themes of black liberation and personalized reflection. This exchange is best exemplified by a monumental Shani Peters work. It is a floor-to-ceiling photographic installation featuring images of the 1992 LA riots, the Million Man March, and others. The work, 17,195 Sunrises (2019), references the number of days between Stokely Carmichael’s public use of the phrase “Black Power” and the creation of the Black Lives Matter movement. The images are distorted with colorful digital filters, rendering them nearly unrecognizable. Across the lower half of the installation are four panels with short, abstract phrases carved into each. The reference to black struggle is evident, but it requires dutiful engagement to understand the artist’s poetic meaning.

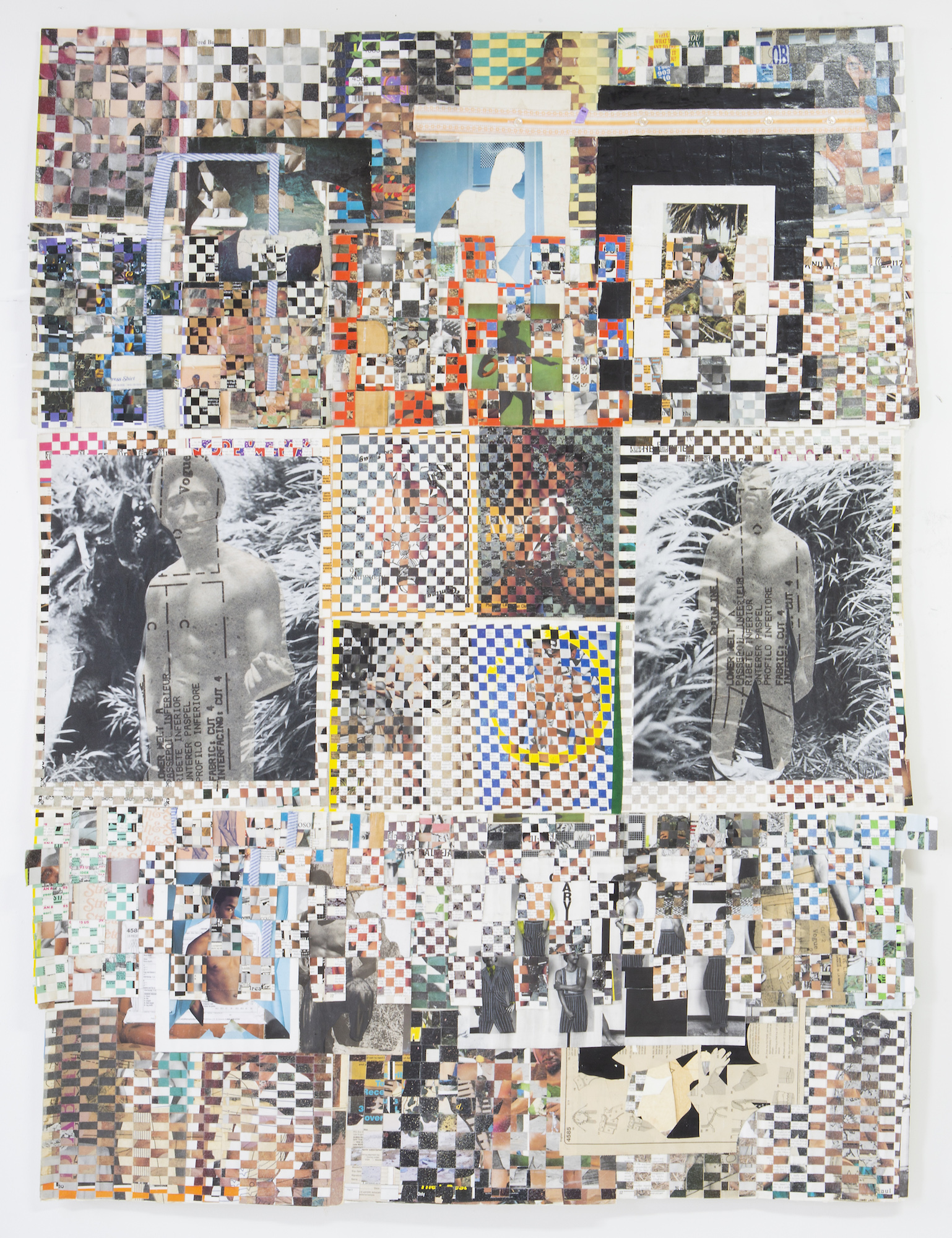

Building on the conversation between intimate experiences and broader realities, two works by Troy Michie explore civil rights narratives through personal reflections. Cuentas Claras, Amistades Largas and This street long. It real long. (2018) are works of collage. Combinations of paper weaving, photographs, acrylic, and other materials, they reference black lives interrupted by the concept of whiteness.

The exhibition concludes with an interactive space where books relating to the multiple narratives of race explored in the show are made available. Audience members are invited to sit, read, absorb, and reflect. Great Force contributes to an evolving conversation about race in America—one that works against the dehumanizing constructs of racism—not with a loud voice and raised fist, but via the work of artists whose humanity is expressed through subtle emotion, simmering realization, and necessary reflection.

If you’re looking for a show to punch you in the gut, you may be hard-pressed to find it here. Great Force takes the long way to the heart. It is in the accumulation of these artworks, and the consideration of their deep meaning, that you may arrive at an emotional crescendo demanding of your attention … and, ideally, your conversation.

This review originally appeared in ART PAPERS Winter 2019/2020 “Global(isms).”

Josh Epperson is a writer and thinker living in Richmond, VA. When he’s not putting words together, he’s insatiably exploring museums, forests, and libraries to uncover new ideas.