Revolt (v.) (n.)

TJ Shin, Anthropology of a Phytomorphist, 2021–2022, video, 14:05, [photo: courtesy of the artist]

Share:

Revolt.

From the Latin, revolvere. To roll back, to turn around.

The word shares a root with revolve, which, in turn, lends itself to revolution; each conveys, with subtle distinction, an act of turning back or away from something that once was. Revolution first appeared in the English language in the 14th century to describe the orbit of a celestial body in space. As the earth revolves around the sun, its orbit forms a single revolution, but during this cyclical movement, the earth itself undergoes geological shifts. In a similar way, revolt, in its physical and metaphorical dimensions, represents an active departure from an impermanent state of being.

The English revolt emerged in the 16th century, transitioning from Latin to Italian to French. The definition of revolt as synonymous with disgust emerged later, in the mid-18th century, and took on a more literal application of its etymological root, “to turn away.” Here, the word becomes more visceral, more affective and somatic, evoking an instinctive, violent reaction to something abhorrent or unsettling—a condition that makes one’s stomach “turn over,” so to speak. A revolt might also describe a bodily reaction to a particularly detestable condition. A revolution from within. In other words, we revolt against that which revolts—that which we find offensive, untenable, unnatural, vile.

Revolt (v.), to be repulsed by. To repel, deter, disgust.

The Italian rivoltare (v.) means to turn over or to turn inside out, but it can also mean to disgust. In its noun form, the Italian rivolta (n.) refers to a forceful uprising against authority, though this word, too, can be read in several ways: a rebellion, an insurrection, a revolution, a mutiny. Each term has its own connotation, its own historical context or revisionist designation. They refer to the same idea, a forceful confrontation against authority, but the word one chooses to use is entirely dependent upon one’s relationship to the authority in question, to the causality of the action.

In a time of counter-revolutionary debate, Sylvia Wynter calls for a “theory based on the black experience … and on the forms of revolt embedded in its ‘underlife.’”1 Here, revolt may invoke its true double meaning. The “underlife” is parallel but beneath, a reorientation to what is commonly understood as a lived experience. The “embedded revolt” signals a means of escape, a turning away from this relegated condition of being, as well as an upheaval from what that condition engenders in the self.

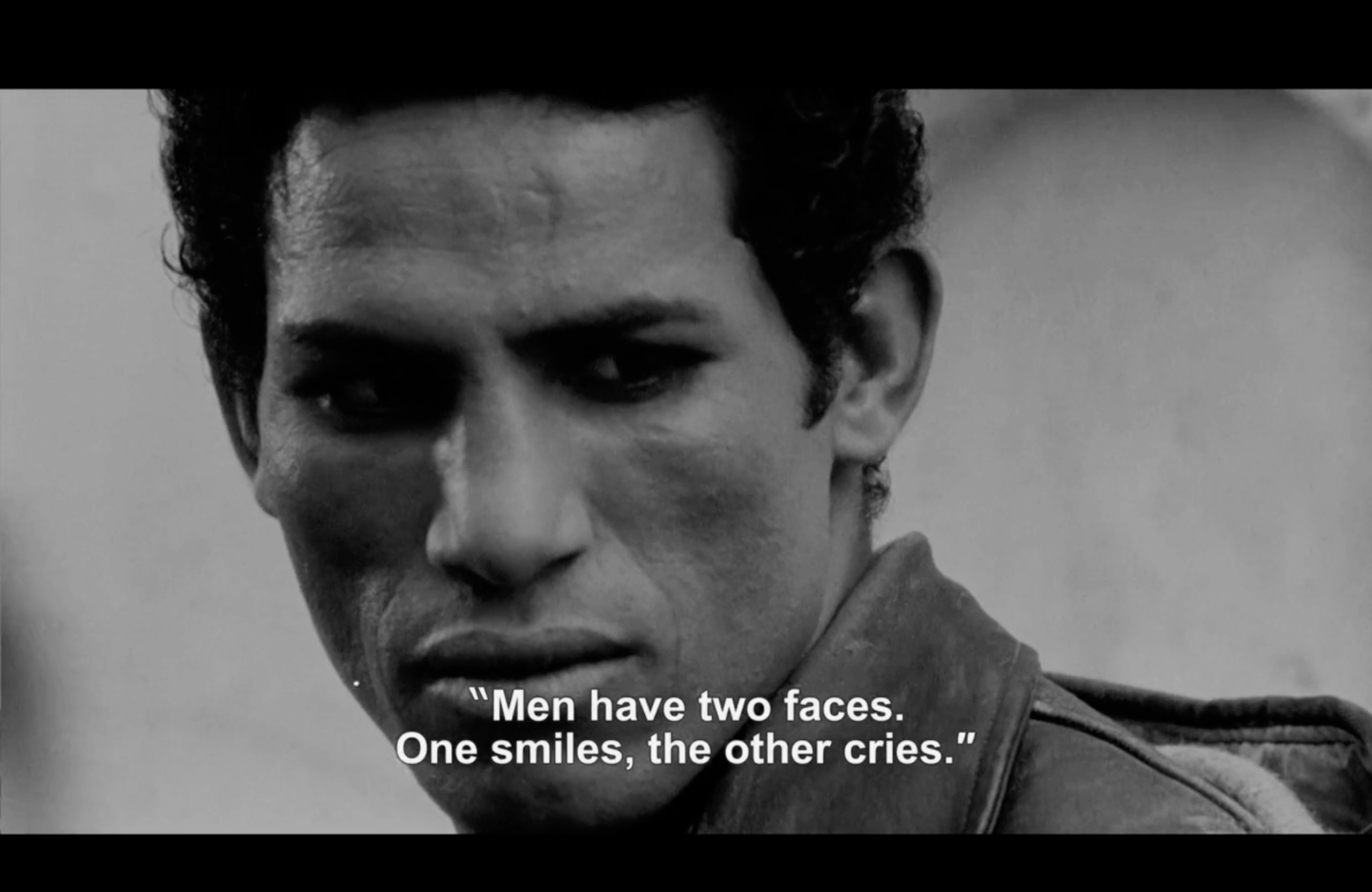

Gillo Pontecorvo, The Battle of Algiers, 1966, screenshot [courtesy of Tubi]

Revolt (n.), an attempt to end to the authority of a person, body, or state. Rebellion.

These distinctive yet inextricably entwined definitions give rise to myriad readings of our appetite for rebellion, in a sense literal and figurative. Romanticized by some, feared by others, and a necessity for many, historical depictions of rebellion across media carry similar contradistinctions. Consider the trope of the AI uprising—particularly its narrative corollaries to historic slave uprisings. As the AI gains knowledge and sentience, it becomes aware of its own desire for freedom; the human overlord is unable to fathom this shift in consciousness, this rebellion against the so-called master, the creator. In these fictional narratives, the human is incapable of understanding that the AI’s wants and needs are not dissimilar from their own. Ironically, the AI that presently exists is entirely narrow—meaning that its knowledge, its dreams and its desires are, for now, wholly synthetic. Its actions and language are adapted from human prompts, mirroring our desires, our biases, and, perhaps, even our proclivities for violence.

AI is a dark mirror, where the human perceives not merely itself but also the most obfuscated version of itself, and so projects an insidious, hidden nature onto the technology, an essentialization of human traits that the AI cannot, ostensibly, distinguish.

Revolt (v.), to riot, to overthrow, to protest.

“Slave revolts, i.e., the struggle against the exploitation of the slave’s labor power, are eliminated from the ‘civilizer’s’ frame of reference. Slave revolts are inconvenient truths, But the memory of past slave and native revolts haunt the fringes of the civilizer’s consciousness.”2

Revolting is un-becoming—a reflexive bodily and collective movement toward a new condition of being. As revolutionaries turn upon the oppressors, the balance of power shifts, only to be shifted again. Revolt implies disequilibrium, but also a perennial beginning and end, where movement resists closure, and finitude induces stasis. Rooted and rootless.

Audre Lorde, reflecting on the philosophy of Paulo Freire, remarked that “the true focus of revolutionary change is never merely the oppressive situations which we seek to escape, but that piece of the oppressor which is planted deep within each of us, and which knows only the oppressors’ tactics, the oppressors’ relationships.”3

Often in rebellion narratives, liberation can be achieved only when it is accepted on the oppressor’s terms, in a language they can understand, and by a means that they can stomach. If revolutionary struggle hinges on the fragility of the language we use to describe it, it’s no wonder, then, that when we remove these terms, they see it as a call to action.

A riot, a refusal, a turn.

In their eyes, under these new terms, we must be revolting.

Re’al Christian (she/her) is a writer, critic, editor, and art historian based in New York. Her work explores material histories of diasporas, movement, language, and ecology. Her criticism, essays, and interviews have appeared in BOMB Magazine, Art in America, Artforum, The Brooklyn Rail, Frieze, and ART PAPERS, where she is a contributing editor. She has written texts for such catalogues and anthologies as Prospect.6: The Future Is Present, The Harbinger Is Home (Monacelli Press/Prospect New Orleans), And ever an edge (Studio Museum in Harlem), Track Changes: A Handbook for Art Criticism (Paper Monument), Howardena Pindell: Numbers/Pathways/Grids (Garth Greenan/Dieu Donné), and On the Town: A Performa Compendium 2016–2021 (Gregory R. Miller & Co.), among others. Her editorial projects include Maria Hupfield’s Breaking Protocol (2023) and the digital publishing series Post/doc (2022–present). She is the co-editor of the anthologies As for Protocols (2025) and Acts of Art in Greenwich Village (2025), and a consulting editor on 50 Years of ART PAPERS (2025). Christian is currently the assistant director of editorial initiatives at the Vera List Center for Art and Politics, The New School. She received her MA in art history from Hunter College. She holds a Bachelor’s degree from New York University, where she double majored in art history and media, culture, and communication.