monument (n.)

Sharon Hayes, If They Should Ask, Rittenhouse Square, Philadelphia, Monument Lab, 2017 [Steve Weinik/Mural Arts Philadelphia]

Share:

An acrostic for MONUMENT:

Movement. Demands for profound changes to our systems of law enforcement have shifted the monument landscape—a landscape dotted with symbols that carry the burdensome weight of settler-colonial logics, shaped by the aesthetics of oppressive whiteness.

To move toward justice is also to move back in time in an act of recovery. Liberation requires the retrieval and un-silencing of histories, archives, and memories that powerholders have violently repressed.

These movements emerge from us—but who are we?

Outsider. We are a coalition of Outsiders, “forged in the crucibles of difference,” who embody racial, gender, sexual, and class identities that are perceived as incompatible with the norms of White patriarchal capitalism.1The margins are a space of survival, resistance, and catalytic change.

Through the tools and knowledge systems we create, we reclaim our public spaces to reflect the experiences of the Outsider. Collective rage is our intervention and our most precious monument.

Neutrality is a lie. Public space is not neutral, and monuments are deeply intertwined with systems of power. The production of space (like history, facts, data, and so on) is a mode of consolidating and exerting power.2

Historically, public spaces undergird normative power dynamics by reflecting specific narratives of progress, triumph, or permanence, and by simultaneously under-protecting and over-surveilling Outsiders.

Although monuments are often sites of conflict, they also have the potential to provide spaces for meaningful confrontation and repair.

Undoing the system. Toppling statues and removing racist monuments are only the first steps toward justice. Undoing a system requires collaborative visions for building a new one.

The production and maintenance of a system depend heavily upon history, cultural memory, and art. Artists and activists, together with local communities, must collectively rewrite a process for building monuments, one that elevates historically marginalized stories and re-imagines the ways that history lives with and in us.

Matter. Monuments are not inert or static; they are vibrant matter.3 With their vital agency, they work on and with us.

In the decade prior to 2018, at least 40 million taxpayer dollars went toward the maintenance of Confederate monuments, even as construction of the monstrous US–Mexico border wall has destroyed rare plants, animals, and the sacred ancestral grounds of the Tohono O’odham Nation, thus eradicating and erasing parts of Arizona’s Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument.4

Whose histories and memories are worthy of monuments? Which monuments are deserving of care, maintenance, and sustenance? Whose lives matter?

Embodiments. Monuments—both figural and nonfigural—embody collective identities, as they articulate a set of ideas, values, and truths. Sara Ahmed instructs us that “power works as a mode of directionality,” and that things “orient” our bodies toward certain futures.5 In this way, the corporeal substance of the monument throws into relief the stakes of public space in subject- and world-making.

Narratives. Given the material vitality and corporeality of monuments, the stories we tell in the public sphere must expansively include the perspectives and dynamic modes of knowledge-building that emerge from people whose lives are historically undervalued, or from the Outsider.

New narratives are the tools with which we can confront the deeply rooted myths of heroic Whiteness, the specters of colonialism, and the apathy of our neighbors.

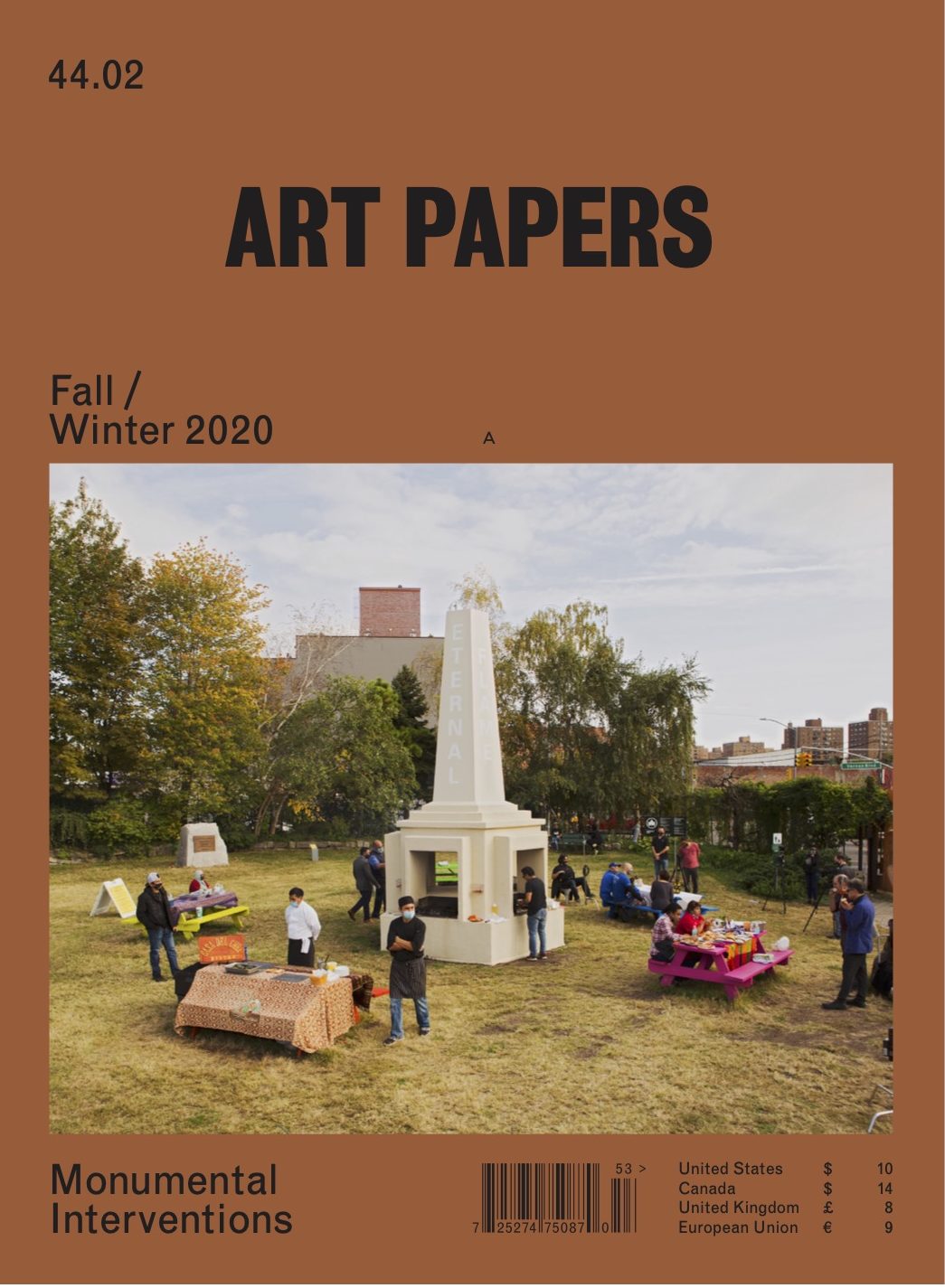

Transformation. Changes to the monument landscape do not necessarily promise the sweeping reforms that are desperately needed across all sectors, including education, health, housing, law enforcement, immigration, and environmental policy. Nevertheless, these changes are valuable because they spark conversations, connect people, and, most importantly, they tell the truth. Monumental interventions reveal in spectacular fashion the willingness of people to tell the truth about our histories and ourselves—the first of many steps toward transforming the worlds we have inherited.

***

This feature originally appeared in print in ART PAPERS Fall/Winter 2020 // Monumental Interventions.

Patricia Eunji Kim PhD is an art historian, curator, and educator based in New York City. She is assistant professor/faculty fellow at New York University’s Gallatin School of Individualized Study, associate director of public programs at Monument Lab, and editor of the Monument Lab Bulletin. She is writing the first book on the art and archaeology of royal women from the Hellenistic world, and is co-editor of Timescales: Thinking Across Ecological Temporalities (University of Minnesota Press, 2021) and Shaping the Past (Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung, under contract).

References

| ↑1 | Audre Lorde, Sister Outsider (Trumansburg, NY: Crossing Press, 1984), 112. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Michel-Rolph Trouillot, Silencing the Past: Power and Production of History (Boston: Beacon Press, 1995). |

| ↑3 | I borrow this phrase from Jane Bennett’s work on the force of nonhuman things, and their entanglements with and ability to affect humans. Jane Bennett, Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2010). |

| ↑4 | Brian Palmer and Seth Freed Wessler, “The Costs of the Confederacy,” Smithsonian Magazine, December 2018, online. Monument Lab Podcast, episode 23, “Bearing Witness in the U.S.–Mexico Borderlands with Conservationist Laiken Jordahl,” online. |

| ↑5 | Sara Ahmed, Living a Feminist Life (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2017). |