daddy

Share:

Every week, after the Friday prayer, my dad would drag me along with him to the main fish market in Kuwait—where I lived until I was seventeen—to buy our seafood, raw and wriggling. Fridays were the day to go because that’s when fishermen, fluorescent blurs in their rubber, shin-high boots, would pour basketfuls of slimy fish, shimmering with life, straight from the Persian Gulf, onto the market’s tiled floor for people to bid on.

I hated it.

It was so loud, it fucking reeked; all these cis-presenting men, constant yelling. But worst of all was the tiled floor, which was always wet from the melting ice. There was nothing I despised more than that ice-cold muck-brew splashing on my shoes or my jeans. I would tiptoe behind my dad, a ballerina in disgust, trying to keep up with him as he went from stall to stall; sniffing, touching, poking everything with his fingers and the tip of his nose.. Thinking back, it was probably his embarrassment of my tiptoeing behind him like that which made him not mind so much when I began asking if I could wait in the car till he was done.

He’d come back stinking of a week at sea. I’d be listening to the radio, 99.7 Radio Kuwait FM. He would be so proud of the deals he’d made. I would nod and hum at appropriate intervals, as if I was actually listening to a word he was saying. We’d get home, and he’d go straight to the kitchen to butcher and portion the fish into various cuts, stinking up the whole apartment, calling me in to “Come look at all this roe!” I’d reluctantly heed his call and watch as he carefully pulled out veiny, glistening sacs from the butterflied body of a fish. His face: A mad gambler collecting his winnings. My face: Utter repulsion. Embarrassed to be related to this man but amused by what was so amusing to him. This man, belly hanging out from under his tank top, which was by that point stained with congealed fish blood. This man, whose fish-mongering antics resulted in annoyingly delicious meals.

I was taught that Friday prayers are more of an obligation for men than for women. I was taught that the prayer had to be performed in the mosque to count as a Friday prayer—as opposed to the regular noon prayer which is performed at the same time every other day of the week. Women could technically go and follow along through the speakers in their separate quarters. But they didn’t really have to do all that. They could just pray at home (when patriarchy has a silver lining). The Friday prayer sermon is a prerequisite to the service, and my dad hated imams that took longer than twenty minutes to get to the actual prayer portion of the program. He avoided mosques whose imams got too emotional, or those who shouted their sermons. But, most of all, he hated imams who had that special showmanship combo of shouting out their sermons so emotionally that their voice would break in cringey devotion. Those kinds of deliveries made us both wince.

I haven’t been to a mosque in Kuwait for Friday prayer with my dad in fourteen years, and I’m not mad about that. Sometimes—more often these days—I get the urge to stray from our typical, “Hello, I’m still alive” weekly WhatsApp script. I daydream about asking him how they’ve been recording the Friday prayer sermons, now that boomboxes are obsolete. But every time I’ve ventured something more substantial than just doing the least to keep in touch, it’s backfired. He takes it as permission to start asking me uninvited questions about my life, questions I would prefer not to answer, for his own good, and my own sanity.

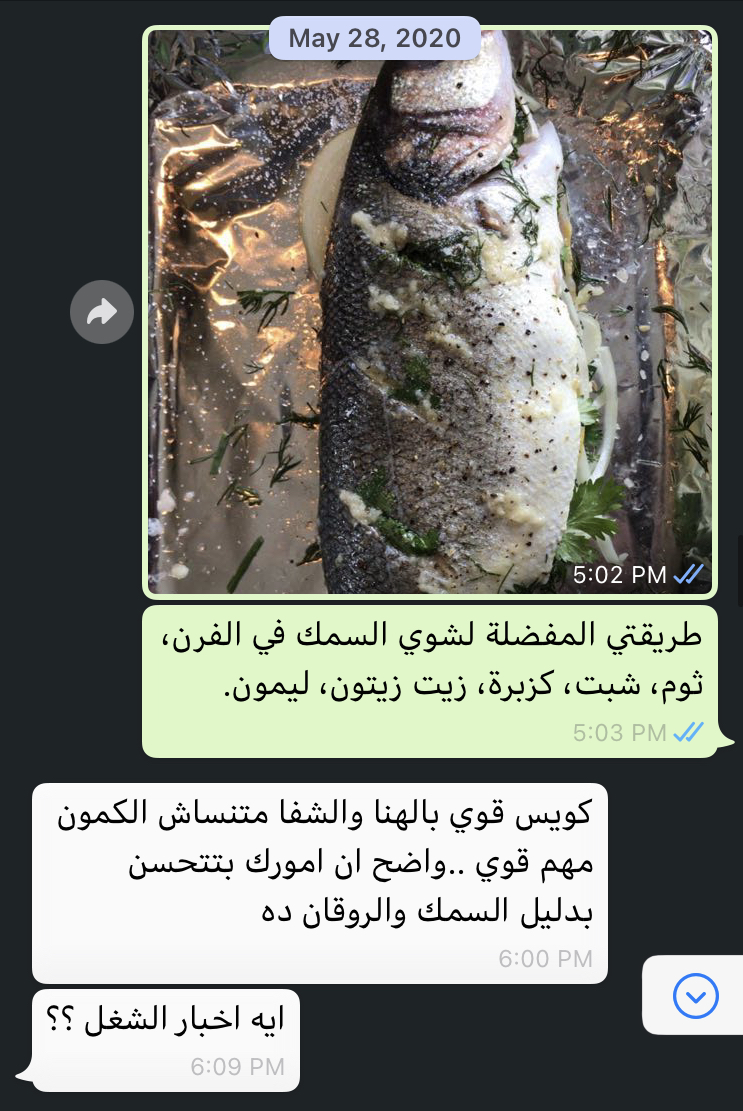

When I’m feeling cute, and this happens only very sporadically, I will allow myself to message him asking for the recipe to his cilantro, tail-on shrimp, or his tomatoey, oven-baked fish, and he will gladly oblige. I don’t think I’ll eat a meal cooked by my dad or attend a Friday service with him again. Even if I wanted to, I wouldn’t pass in either gender’s prayer room, which I’m definitely not mad about. After running away for so long to be with myself, I don’t think I could ever masquerade as anything other than myself again. Not for his pleasure, or my safety. So, I collect his recipes and integrate them into my notebooks for the seafood market/restaurant I will one day open. And I cuss myself out, laughingly, in my head, for how much I now enjoy the experience of buying and preparing fresh seafood.

Shehab Awad is an independent curator and writer from Cairo, Egypt, currently based in New York City. He/she is founding director of Executive Care, an all-encompassing agency at the service of artists.