Gina Adams: Its Honor Is Hereby Pledged

Gina Adams, Broken Treaty Quilts, 2013-ongoing, hand-cut calico fabric letters with cotton thread on antique quilt, approx. 68 x 92 inches [photo: Jeff Wells; courtesy of Gina Adams and Accola Griefen Fine Art, New York, CU Art Museum, Boulder, CO]

Share:

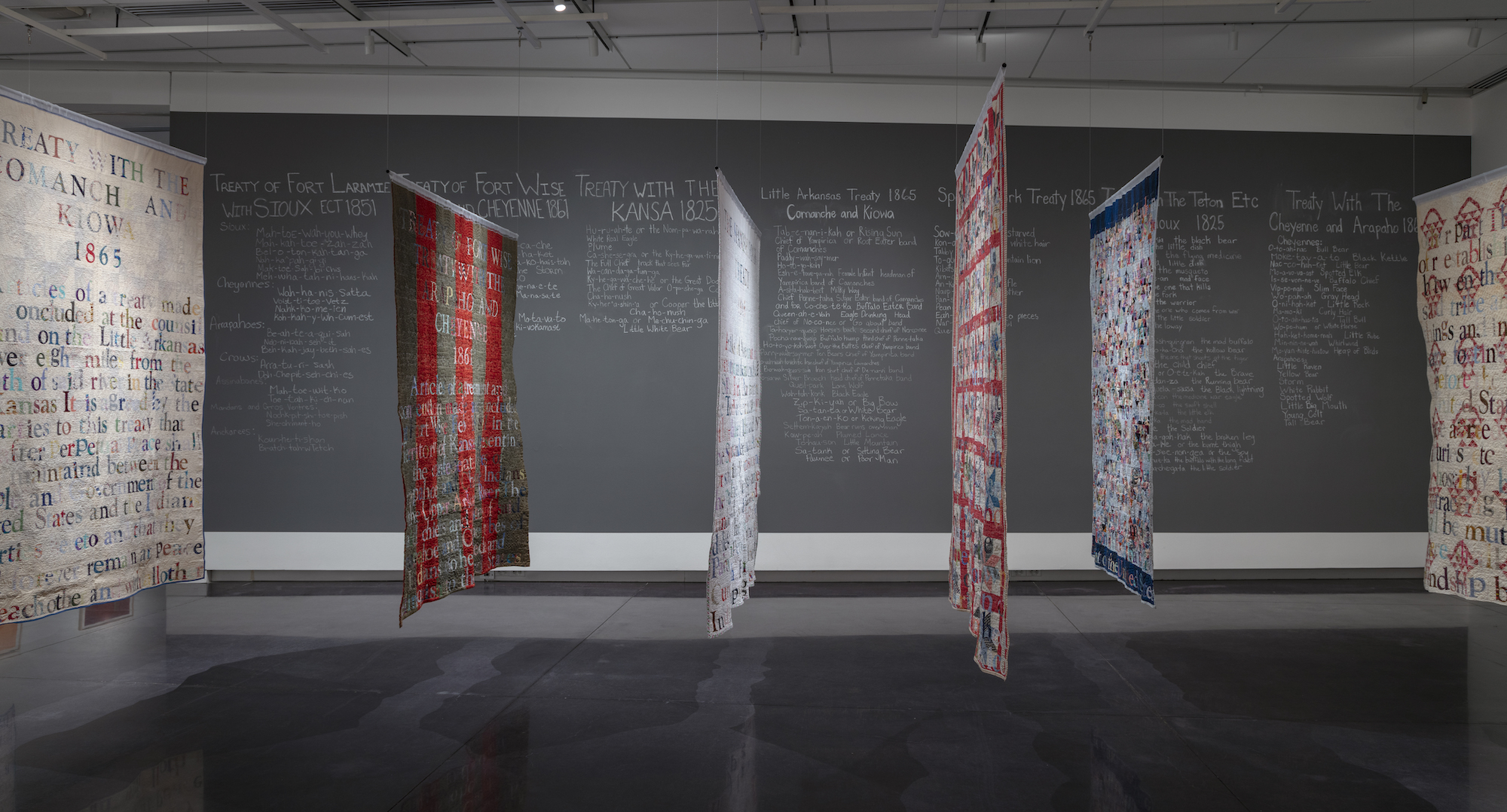

American pioneers would spend up to a year preparing for a trip west. In addition to provisions, prepared settlers packed several blankets per family member, which provided privacy, shelter from the dusty wind, and protection for fragile treasures on the rocky route. Fabric patterns and family names sleep between the seams of early American quilts, providing historians a material record of a young country. Ten such specimens from 1850 to the early 20th century were suspended from the ceiling of the University of Colorado Art Museum. Adorned with stars of Bethlehem and Dutch baskets, these quilts seemed to float; generously spaced to encourage passage among them, the bedcovers quivered and bowed to any nearby movement. The freshly stitched texts of old US land treaties played hide and seek among the aesthetics of settler culture. In the exhibition Its Honor Is Hereby Pledged, Gina Adams reframed these old promises—and the chiefs who signed them—to argue that the most devastating weapons non-Natives laid upon indigenous people have been assimilation and bureaucracy.

Treaties defined and documented the relationship between the US and Native nations. Their impacts ripple through Indian country today despite the fact that most were amended, nullified, or broken. Adams mediates the legibility of land rights by threading treaty language in calico letters onto the busy surface of each quilt. The visual noise quiets only when the text runs over and around the edges onto the rarely exposed plain fabric on the backside of each blanket.

In the series Broken Treaty Quilts (2013–ongoing), the rainbow lettering of Adams’ Dawes Act 1887 beckons from its pillowy support. Despite the enormous impact of Dawes, this treaty is overshadowed by the violent events that preceded its legislation. President Andrew Jackson refused to enforce the Supreme Court ruling in Worchester v. Georgia (1832), which held that state law did not apply to sovereign Native American land. He then signed the 1830 Indian Removal Act into law. Cherokee, Seminole, Choctaw, Chickasaw, and Muskogee (Creek) peoples—including the aged, the sick, and infants—were rounded up at gunpoint and marched thousands of miles. Jackson promised the land that is now Oklahoma would be Indian country “as long as grass grows or water runs,” but what followed was the Dawes Act. It divided established reservations into predetermined plots distributed to indigenous individuals and families, rather than to tribes, a practice known as allotment. The parcels for a landowner were often separated by hundreds of miles, which enabled land-grabbing by white squatters.

Gina Adams, Broken Treaty Quilts, 2013-ongoing, hand-cut calico fabric letters with cotton thread on antique quilt, approx. 68 x 92 inches [photo: Jeff Wells; courtesy of Gina Adams and Accola Griefen Fine Art, New York, CU Art Museum, Boulder, CO]

The objective of Dawes was to split up Indian land, argues Rebecca Nagle, citizen of the Cherokee Nation and host of the podcast This Land. Allotment in Oklahoma also meant that if the land was sold or fell out of the hands of the original family, it was no longer reservation land. According to Nagle, more than 100 reservations in the US went through allotment, and tribes lost two thirds of their land base without a shot being fired. Today, only 2% of American soil is Indian country—about 55 million acres.

Gina Adams’ investigations are timely. This year the US Supreme Court heard arguments in a case that could reaffirm the original reservation borders of the Muscogee (Creek) nation, which makes up almost half of Oklahoma. The case Sharp v. Murphy (ongoing) started with a murder confession by one Muscogee (Creek) Nation citizen of another. It was discovered that the crime occurred on land lost to allotment, but land in which a Muscogee (Creek) family retained the mineral rights. If the land were a quilt, the analogy would be that they sold the fabric but kept the stuffing. In questioning the state’s authority to prosecute the case, the defense proposed that allotment never dissolved the reservation’s borders, as outlined by a treaty. The court scheduled the case for reargument in the next session, a rare action notably taken in cases such as Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka (1954) and Roe v. Wade (1973).

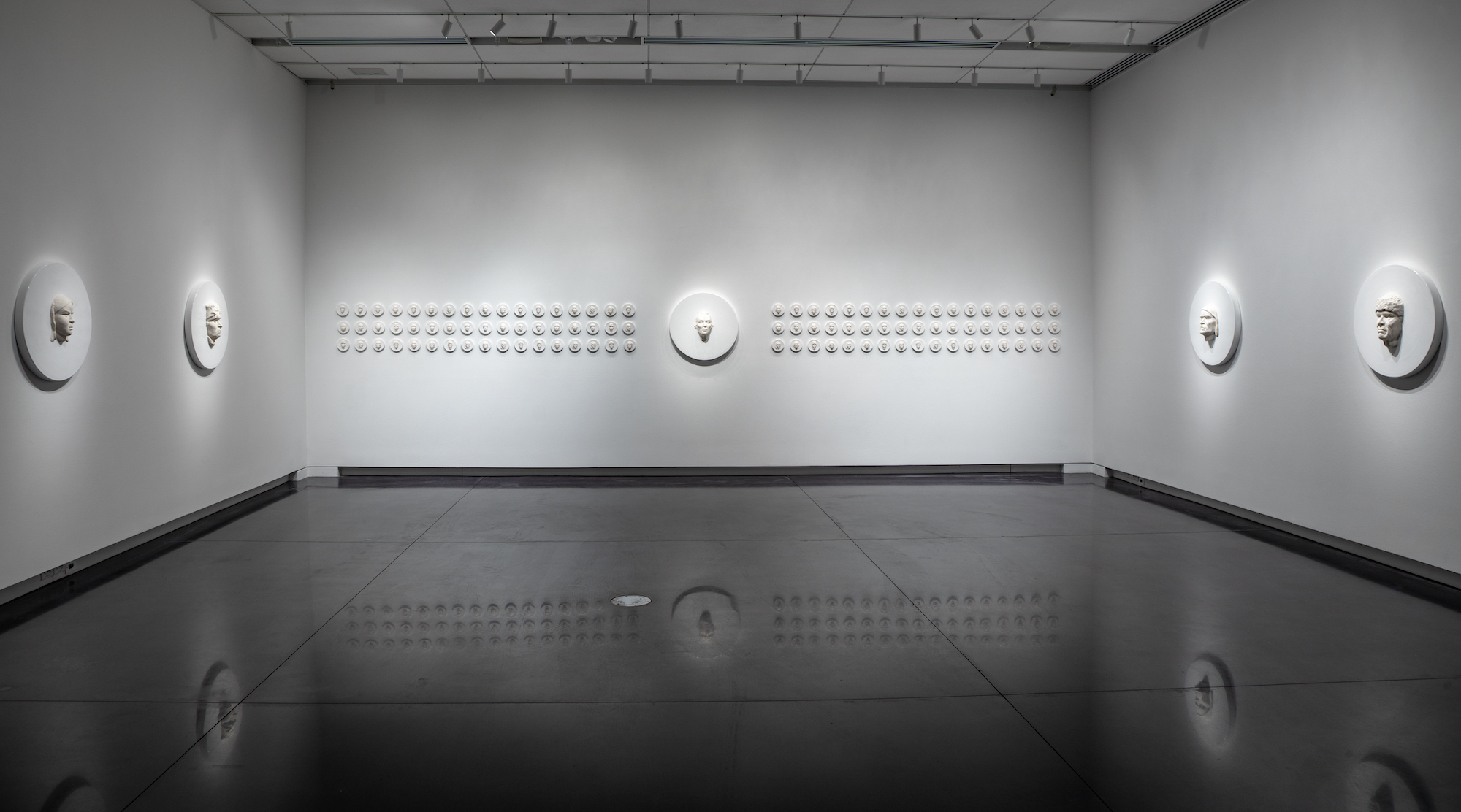

In my correspondence with the artist, Adams stated: “My grandfather’s people were forced onto the White Earth Reservation in Minnesota, but the entire family and Ojibwa band of people are originally from the Saint Lawrence River, the Great Lakes region and the Mississippi River.” Adams’ kin stare out from mock presidential peace medals in Ancestor Medallions (2019) resembling ones awarded to chiefs who signed treaties. The originals were made of silver, but they would glow white in photographs, like Adams’s contemporary versions produced in porcelain. The artist replaced the profiles of sitting presidents with reliefs of her elders. The unglazed faces acknowledge the material’s earthen origins while the glazed luster of the surrounding surface marks the medallion as a symbolic rupture with the soil.

Gina Adams, Ancestor Medallions, 2019, 102 porcelain with slip and white glaze, 4 ¼ diameter x 1 ½ inches, Cast by Mudshark Studios, Portland, OR [photo: Jeff Wells; courtesy of Gina Adams and Accola Griefen Fine Art, New York, CU Art Museum, Boulder, CO]

The names signed to the quilted treaties were listed below each treaty name on a long chalkboard across the room from Adams’ watchful ancestors. Titled Signers Wall (2019), the unceremonious medium hosted the phonetic spellings and translated names typical of treaties, requiring only an X-mark by male tribal members or leaders. A wall label claimed that Adams honors signatories by inscribing their name on a chalkboard—a medium of Euro-American education—but there is something amiss with that assertion. Throughout the exhibition Adams replaced the authority of history’s narrators in unexpected ways. The names and faces of US presidents were not in the room, and the named chiefs who agreed to sell land, either by force or for personal interest, were chalk dust by the show’s conclusion. Who are the heroes in these stories? Were these chiefs viewed as traitors by their communities? Nagle notes that a large majority of Cherokee protested the Treaty of New Echota, which ceded their land. John Ridge, a tribal leader who signed it, was later killed by fellow Cherokee. The people who safeguarded language, families, and traditions never reach the schoolhouse history books.

It felt as if something was missing in the exhibition because Adams tells a story of erasure through the language of the colonizer. Utilitarian textiles, trophies, and schoolhouse blackboards shed their benign contexts in Adams’ interventions and loudly announce the stories absent from historical or contemporary discourse. The events or testimonials around the quilted treaties were not available to viewers in the room. The artist’s choices surprisingly pull at us to consider why. If the Dawes Act took land, and the Curtis Act stole language and children, dismantling tribal governance for settler assimilation was a form of genocide. American history, as taught in schools and repeated in popular culture, is not an epic victory or grand experiment. It is a selectively incomplete story, which is another way of saying a lie.

And lies always have holes.

Kealey Boyd is a writer and art critic. She is a regular contributor to Hyperallergic, and published with College Art Association (CAA Reviews), Artillery Magazine and others. She is the art consultant to the national literary journal, Copper Nickel, and a lecturer in Art History and Theory at Metropolitan State University of Denver. Her research interests include methodologies for interpreting painting and other visual forms as an integral element of political and cultural discourses.