Frederick Douglass: Embers of Freedom

Raphaël Barontini and the Savannah High School marching band, “Parade Opera: A Living Tribute to Frederick Douglass,” 2019, opening performance, “The Golden March,” [courtesy of SCAD, Savannah]

Share:

Frederick Douglass (1818–1895) was an American social reformer, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman who was born into slavery. Douglass’ life has been retold through various biographies and through his own words in three autobiographies: Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave (1845), My Bondage and My Freedom (1855), and Life and Times of Frederick Douglass (1881).

Frederick Douglass: Embers of Freedom is the collaborative effort of SCAD Museum of Art and the collection of Walter and Linda Evans. Curated by Humberto Moro, Ben Tollefson, Ariella Wolens, Storm Janse van Rensburg, and Celeste-Marie Bernier, the exhibition takes up multiple perspectives to explore the life and legacy of a multifaceted man. The exhibition is an experiment in interdisciplinary curation that incorporates artworks, technology, and archival materials to explore the prevailing legacies of Douglass’ life. This approach works to place Douglass in a domestic and international framework and to bring his narrative to contemporary art audiences. The exhibition is built around the Frederick Douglass Family Archive, which is in the private collection of Walter and Linda Evans. The Evans’ collection includes Douglass’ family manuscripts, letters, newspaper clippings, and photographs. Selections of these historical objects are here made available to the public for the first time, grounding the exhibition in the ephemera of Douglass’ life.

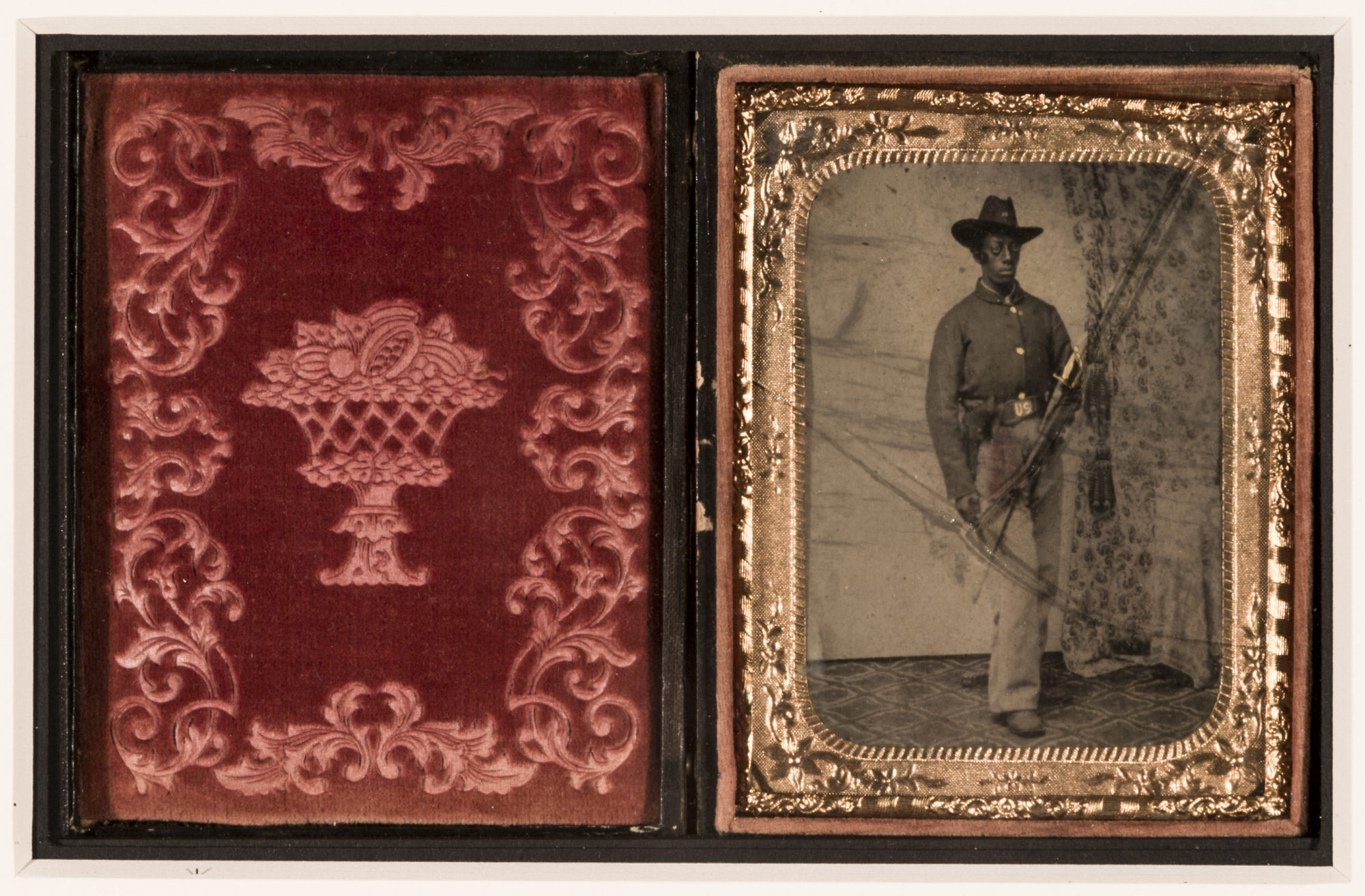

Archival materials appear under glass in large vitrines at the entrance and at the center of the gallery. Included are daguerreotypes of Douglass’ sons in Union uniform, oration pamphlets from Douglass’ various speaking engagements, and somewhat more personal artifacts such as letters written to Douglass from his grandchildren. The most exceptional/remarkable materials presented are a series of family scrapbooks created by Douglass and his sons Lewis Henry, Charles Redmond, and Frederick Jr. The large weathered books include newspaper clippings from 19th-century black newspapers, several of which are not known to have not been preserved elsewhere. The clippings follow Douglass’ years of travel, speaking, and advocacy, and they reveal the commentary and scrutiny the Douglass family faced. The pages include obituaries, letters, and handwritten notes from family members. The books have also been digitized and made accessible through a touchscreen apparatus that allows viewers to scroll through, zoom in, and explore the details of the information.

Photographer Unknown, “Charles Remond Douglass in Military Uniform,” ca. 1863, photograph, 4.8 x 7.7 x 0.3 inches [courtesy of Dr. Walter O. Evans and Linda Evans’ collection, Savannah]

The exhibition addresses the urgency of building and maintaining legacy. By centering the archival material, questions of ownership, preservation, and selective memory are raised. How did these personal artifacts find their way out of the Douglass family’s possession and into a private collection? Who should have access to this material, and how should it be used more than a century later to expand contemporary understanding of Douglass’ life and work? This particular exhibition appears less concerned with painting an ideal image of Douglass and instead uses the archival material to ground the conversation in his complex interpersonal and professional relationships. In leaning away from more mythic depictions of the revolutionary icon, room is left for his humanity. His roles as husband, father, grandfather, and mentor are presented as critical to understanding his greater impact on the world. The archival materials are supplemented by contemporary artworks intended to expand upon the themes expressed through the selected documents. This juxtaposition creates a dialogue between the past and present that spans more than a century. Douglass is presented as both the head of a large family and of a series of social and political thoughts and actions. He was the ember that ignited many of the flames of social justice today.

The contemporary art in the exhibition represents the work of artists of various nationalities, races, and ethnicities. This choice echoes Douglass’ far-reaching influence. Photography, sculpture, prints, paintings, assemblage, and video appear together to illustrate the continuation of a deep-rooted social discourse. The inclusion of many of the artworks can be interpreted through the framework of Douglass as an abolitionist. Some can be read via Douglass’ role as a supporter of women’s rights, others through his oratory or statesmanship. The many thematic threads encourage dialogue across intersecting topics, but they also create some disconnect when taking in the exhibition at large. Works by American artists Betye Saar, TR Ericsson, and Titus Kaphar stand so strongly in their own particular narratives that they distract from the overall conversation. Kaphar’s practice is engaged with shifting historical narratives by reframing how we consume art and art history. The Jerome Project (2014) is a series of portraits of incarcerated men with the same name as Kaphar’s father. The small gold leaf portraits are marred by a tar-like material that obscures the men’s faces, blurring their identities. Kaphar is specifically commenting on the mass incarceration of black men in the United States and how it works to dehumanize a large part of the country’s population. Although the work is powerful, its connection to Douglass in the context of this exhibition is tenuous.

Omar Victor Diop, “Frederick Douglass (1818-1895),” 2014, from the series “Project Diaspora,” pigment inkjet print on Harman Hahnemuhle paper, 35.4 x 35.4 inches [original portrait by Samuel J. Miller; courtesy of the artist and Arnika Dawkins Gallery, Atlanta]

Several of the included artworks make direct and explicit connections to Douglass in concept and visual depictions. Senegalese photographer Omar Diop’s 2014 self-portrait—from his Project Diaspora series—Frederick Douglass (1818–1895) references Douglass on multiple levels. Douglass had a mission to control and reproduce his own image to combat the onslaught of defaming and racist imagery popular in American culture, secure his own legacy, and spread his various messages. Diop’s practice involves his use of his own image to retell and preserve historical narratives. Through this interpretation, Diop honors the legacy of Douglass’ mission and celebrates his achievement of being the most photographed American of the 19th century. The vibrant green paisley pattern used as the backdrop of the photograph repeats in Diop’s vest, catching the eye and outlining Diop’s figure. Meanwhile, the gold whistle clasped in Diop’s fingers competes for the viewers’ attention, pulling their gaze away from the intensity of his eyes.

This effect emphasizes Diop’s silhouette, blurring his individual identity and enhancing the evocation of Douglass’ iconic outline. The illusion is accentuated by the placement of Diop’s portrait alongside untitled portraits of some of Douglass’ children by American painter Charles Edward Williams and a drawn portrait of Douglass by American artist Charles White.

Nigerian artist and archivist Onyedika Chuke’s sculptural installations are part of an ongoing project called The Forever Museum Archive (2011–present), in which he creates and presents objects, images, and texts to critically interrogate space and social structures. In this installation, Chuke comments on valuations of the human body that date back to the transatlantic trade of enslaved black people. He brings Douglass’ international abolitionist efforts to the present moment and places them in conversation with discourses upon environmental terrorism, sexual slavery, and the organ trade—wherein most of the victims are women and children of color. His work includes large sculpted hearts, lungs, and rust-colored feet placed haphazardly in the open space of the gallery, making them difficult to ignore. The objects are anchored by a large chain-wrapped flagpole supporting two draped flags, one of which displays the co-opted slogan “DON’T TREAD ON ME.” The objects confront the viewer and take up space so that it is impossible to not contend with them and, ideally, the larger social ills they embody. Chuke’s installation, along with a mixed media collage titled Obsessão II (2017) by American artist Lyle Ashton Harris, and 2018 Off the Shelf prints by American artist Martha Rosler expand on Douglass’ work through themes of personal archiving and legacy building.

Isaac Julien, “Frederick Douglass: Lessons of the Hour,” installation view, 2019, [courtesy of SCAD, Savannah]

French artist Raphaël Barontini’s The Golden March was commissioned to fill SCADMOA’s four exterior galleries known as the Jewel Boxes. The artist paints and prints on fiber to create flags, sails, and banners, objects used to proclaim and confront. The various works on display feature Douglass’ image on metallic fabrics and in bright colors that command attention and communicate urgency. The Jewel Boxes are visible from the street and sidewalk along Turner Boulevard, allowing visitors of the museum and the wider public to see Barontini’s work. The work in each box builds on that of its neighbor to provide a brief narrative of Douglass’ life, from enslavement to revolutionary iconhood. Barontini’s works were officially unveiled in a performance titled Parade Opera: A Living Tribute to Frederick Douglass. The “opera” was a collaboration between the artist and the Savannah High School marching band. A small audience of museum visitors and members of the Savannah community watched the performance, with band members carrying banners in a street procession and performing “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” a song also called the black national anthem. Barontini’s living tribute brought a predominantly black group of high school students into the museum and expanded the museum onto the street.

Art, technology, and archive intersect brilliantly in English filmmaker Isaac Julien’s film Lessons of the Hour—Frederick Douglass (2019), on view in the experimental gallery. Adapted from the film’s original 10-channel installation, it appears here in conversation with the Embers of Freedom exhibition and Barontini’s The Golden March. Lessons of the Hour uses the medium of cinema to create a portrait of Douglass that floats between reality and fantasy, much in the way of contemporary icons. Through emotive acting, monotony, and meticulous mise-en-scène, Julien creates a rich image of the past that is so vivid and lush it appears tactile. The episodic film characterizes Douglass through performance of his most famous speeches, but in contrast it also humanizes him through moments of solitary travel and exchanges of touch with his first wife, Anna Murray-Douglass. Time is obscured through subtle shifts in setting, ingeniously implying the enduring relevance of Douglass’ words in the present. Barontini’s performance and Julien’s film so thoroughly expand upon the content of the archival materials—and respond to it—that the distinctions among the three separate exhibitions weakens the overall impact of the works and the archival material.

The suite of exhibitions on Frederick Douglass works as a measure of progress. The contemporary art acts as a response to a pervading question, how far have we come since Douglass’ death in 1895? Still living with the open wounds of chattel slavery, artists continue responding to the same social, cultural, and political issues of Douglass’ time. For some viewers Frederick Douglass: Embers of Freedom may be a critical reflection on the past, but for others it is a call to persevere in the present.

“Frederick Douglass: Embers of Freedom” is on view at SCAD Museum of Art from October 3, 2019 — January 5, 2020.

TK Smith is a writer, researcher, and aspiring curator of American art. His interests lie at the intersections of art, material, and race.