Flipper, 1963 [courtesy of Wikimedia Commons]

Flipper, Cousteau, and Homo aquaticus

Share:

The broadcast of Flipper and Jacques Cousteau’s documentaries introduced audiences to a seemingly alien world. But these popular shows sought to convince the viewer that the ocean was only temporarily unlivable to humans. Through technology and evolution, humanity would eventually colonize the last wilderness on the planet. What can this era of television tell us about how humans were taught to view the ocean and how these imperial and colonial visions have come to shape the submarine realm in the Anthropocene?

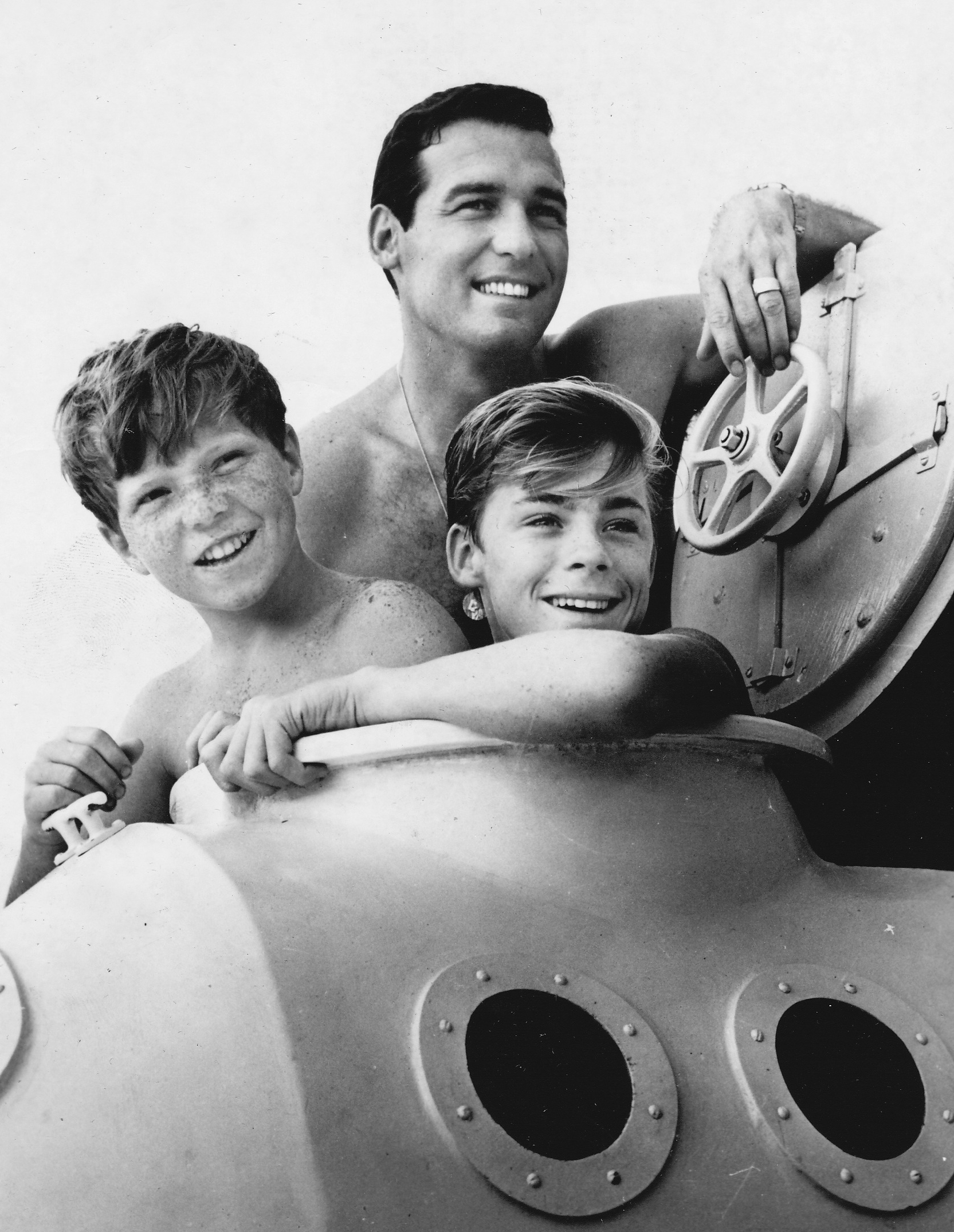

In 1964, NBC introduced TV audiences to Flipper. The show, loosely based upon a 1963 movie of the same name, centers a father and his two sons navigating life in the Florida Keys with the help of a dolphin companion. Flipper is a semi-domesticated dolphin who lives off the coast of the fictional Coral Key Park and Marine Preserve. As in several animal-centered shows of the era—including Lassie and Mister Ed—Flipper can communicate with (some) humans and often helps solve human problems. Despite those similarities, the marine setting forced the writers to think creatively about how to make the submarine environment approachable and understandable to viewers. To do so, the writers relied heavily upon imagining a world in which humans are capable of a semi-aquatic lifestyle.

During the 1960s, Jacques Cousteau believed that semi-aquatic humans, capable of living underwater and communicating with other species, were the next step in human evolution. Cousteau and Emile Gagnan designed the first successful open-circuit SCUBA equipment, called the Aqua-Lung, in 1942. By the time Flipper was on screen, more than 6 million Americans were using the technology. Cousteau believed that humans would soon colonize the ocean, with major underwater settlements. And eventually, he believed humans would evolve the ability to live underwater without technological assistance. Cousteau’s vision of Homo aquaticus was reinforced by his films. In The Silent World (1956) humans are shown interacting with the ocean through use of high-tech submersibles and diving equipment.

This aquatic future was integral to Flipper. The show used several devices to intimate the development of Homo aquaticus. Humans switched seamlessly from land to water by using technology. SCUBA equipment is shown in every episode, and whereas adults sometimes show fear or difficulty in its use, the two youngsters spend hours diving underwater. But the children also are shown free-diving with Flipper. Technology and evolution collaborate toward Cousteau’s imagined future.

Flipper, 1964 [courtesy of Wikimedia Commons]

In addition, the show introduced the personal submersible. First appearing in season one, the fictitious sub was used by characters to spend long periods of time underwater. This craft gave the driver the ability to blend into these environments and to have extensive interactions with Flipper. This technology was not available at the time, but it is one that shows what many thought would be the next step in human/marine interactions.

The show also explores the idea of how humans have changed that space to suit them. In one episode, we see an artificial reef built from old automobiles. In another, action takes place in a sunken ship. In most of these spaces, human architecture becomes naturalized over time, after having been underwater long enough to be covered in algae and coral, and to be inhabited by fish and crabs. Flipper and humans live together in the ocean created by and for them both.

Flipper, 1963 [courtesy of Wikimedia Commons]

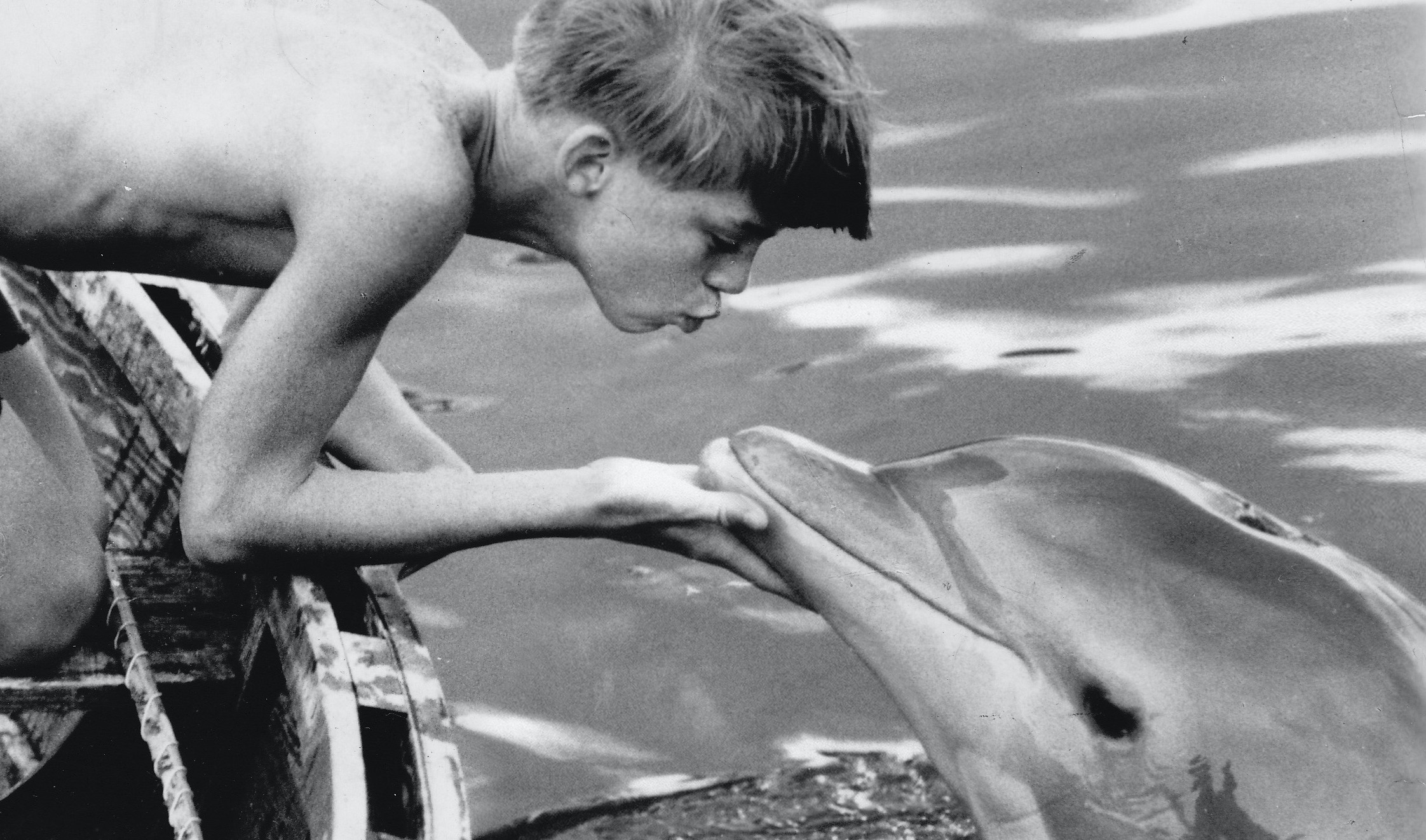

Whereas the mixture of human and animal worlds was shown via technology and architecture, the most prominent future narrative in the show is that of human communication with dolphins. The Miami Seaquarium, home to the dolphins used in filming, was one of the first places in the world where audiences could watch captive dolphin shows. Seaquarium trained dolphins to perform a variety of tricks, including jumping, “speaking,” and fetching objects on command. The dolphins’ training suggested to the audience that these animals were intelligent and enjoyed interacting with humans. Many of these tricks were featured on Flipper.

Flipper, 1969 [photo: Miami Seaquarium; courtesy of Wikimedia Commons]

The most remarkable technology in the show is one that never truly existed. In the show, humans call Flipper to them by using a tool that looks like a bullhorn. They place it underwater, and it emits a sound that emulates a series of dolphin-produced squeaks and clicks. This technology did not exist, and still doesn’t. But it works to convince the show’s audience that humans know and understand dolphins.

Flipper and Cousteau’s films offered a vision of the ocean that centered humans, not as we were, but as we could evolve to become: Homo aquaticus. This aquatic vision made the ocean knowable. But in knowing it, the audience was urged to shape it to suit their own needs. We see the impact of this way of knowing in the current ocean of the Anthropocene, filled with human artifacts, encroached upon by the terrestrial realm.

Sam Muka is an assistant professor in the Science and Technology Studies Program at the Stevens Institute of Technology in Hoboken, NJ. Her work focuses upon the history and sociology of marine science, with special attention to the way that representations of the ocean affect the cultural and scientific perceptions of that space and its inhabitants. Her first book, Oceans under Glass: Tank Craft and the Sciences of the Seas (University of Chicago Press, 2022), examines the history of aquariums and their impact upon the way we see and think about the ocean today.