Eye Candy Is Dandy

Rashaad Newsome, King of Arms Procession, 2013, performance documentation

Share:

You might know Rashaad Newsome as the artist who introduced voguing to the Whitney Biennial, rap to Performa 11, and A$AP Mob to fine art. He’s that artist who proclaimed himself “King of Arms” during a midnight ceremony overseen by monks in hoodies and featuring a haunting musical score that blurred hip-hop with religious ritual. You might have encountered Newsome conducting an assembly of Black women making “ghetto gestures” in choral harmony (Shade Compositions, 2009) or, as of late, cruising in the collage-bombed Lambo he premiered during his solo show at the New Orleans Museum of Art. The majestic synthesis of high and low culture and the meaningful intersection of art, fashion, and music that coheres in his video, collage, and sculpture have established Rashaad Newsome as one of today’s most prominent visionary artists. Through the lens of Monica L. Miller’s ontology of the Black dandy, we can assess how Newsome’s work is destabilizing the heteronormative, unchecked male authority we associated with hip-hop and explore the artist’s use of style, posturing, staged rap battles, mixtapes, and dance as the next wave of embodied protest.

Miller describes the Black dandy as an “embodied, animated sign system that deconstructs given and normative categories of identity (elite, white, masculine, heterosexual, patriotic).”1) Rashaad Newsome’s “meta-status symbols” of “pedigree and power”2—regal antiquity meets hip-hop glitterati—articulate clothing and dress as self-conscious manipulation of authority. Newsome’s robust symbols also signify on colonial legacies in which the first dandified Blacks, so called “prestige slaves” of 18th-century Europe, were dressed in velvet and furs, worshipped for their beauty, showered with gifts, and padlocked around the neck.3

Rashaad Newsome, P31:10, 2013, collage in custom frame, 64-inch radius x 8-inch depth

Rashaad Newsome, #1 Stone of Vigilance, 2013, collage in custom frame, 64.75 x 54.75 x 6 inches [images courtesy of the artist]

James Scott termed Black dandyism a fashionable “weapon of the weak.”4 Black males in fancy dress expose the historically spiritual dimensions of the sartorial (slaves were allowed to dress up one day a week, on Sunday)5 and constitute a sexual threat and class critique.6 The Black dandy unveils the performativity of race and class. Embedded in a glittering collage or projected ceremoniously as a video, Newsome’s Black dandy betrays how White privilege and authority rely on arbitrary mannerisms we call class but exchange freely for race. Hip-hop’s embrace of glitz and gold, even chains, and elevation of working-class swag to sovereign status serve to subvert loaded historical signifiers. Fusing western European coats of arms with gilded elements of the Renaissance heraldry tradition and serious hip-hop swagger, Newsome’s work communicates the complex truths characterizing our times and “send[s] a message about power and status.”7

Newsome is certainly not the first artist to use bling and expressive dance to articulate the sociopolitics of swag. As early as 1999, Sanford Biggers designed a floor resembling a mandala (a Buddhist pictogram used for rituals and worship) that became the site of a breakdance competition during the 2002 Battle of the Boroughs. Biggers later melted down bling and made Japanese singing bowls for a bell-choir performance at a Soto Zen Temple in Ibaraki, Japan. Whereas Biggers’ bling piece, titled Hip-Hop Ni Sasagu (In Fond Memory of Hip-Hop), expresses a sort of reverent longing for the golden age of hip-hop, Newsome’s work touches on the aftermath of the rise of commercial rap, quoting hip-hop as the epitome of luxury.

Consider Newsome’s much publicized “rap joust” organized for Performa 11, the festival’s first-ever rap battle, which drew the interest of MTV. Newsome told The New York Times, “Pageantry, battling, and remixing have always been part of heraldic tradition.”8 His work follows a discursive trajectory in which Blacks explore race as necessarily performative, a hybrid space of transcultural dialogue where reciprocity between Self/Other is given. Riding the explosive global stain of hip-hop culture, Newsome’s work exposes what is most visible and unseen. What’s going on in the trap glitters no less than what occurred in the courts and secret societies of old.

Much like Rashaad’s work, which blends the trappings of “White” European sovereignty with the based “God in Me” stance of hip-hop, early modernists used the dandy body to show the way in which the new Black male was a cosmopolitan blend of English and African origins. Writes Miller, the Black dandy was “a figure who expresses with his performative body and dress the fact that modern identity, in both black and white, is necessarily syncretic, or mulatto.”9 Eventually, a more subversive Black dandyism became a “Modernist sign” and “goal”10 for African Americans situated in Harlem. Swag became a bid for power, and by the late 1920s, events such as the annual Hamilton Lodge “Fairy” Ball created a climate in which “drag queens appeared regularly in Harlem’s streets and clubs.”11 In Newsome’s work, androgyny is king. Whether rapping, voguing, or something in between, the gender-neutral body occupies a position of authority.

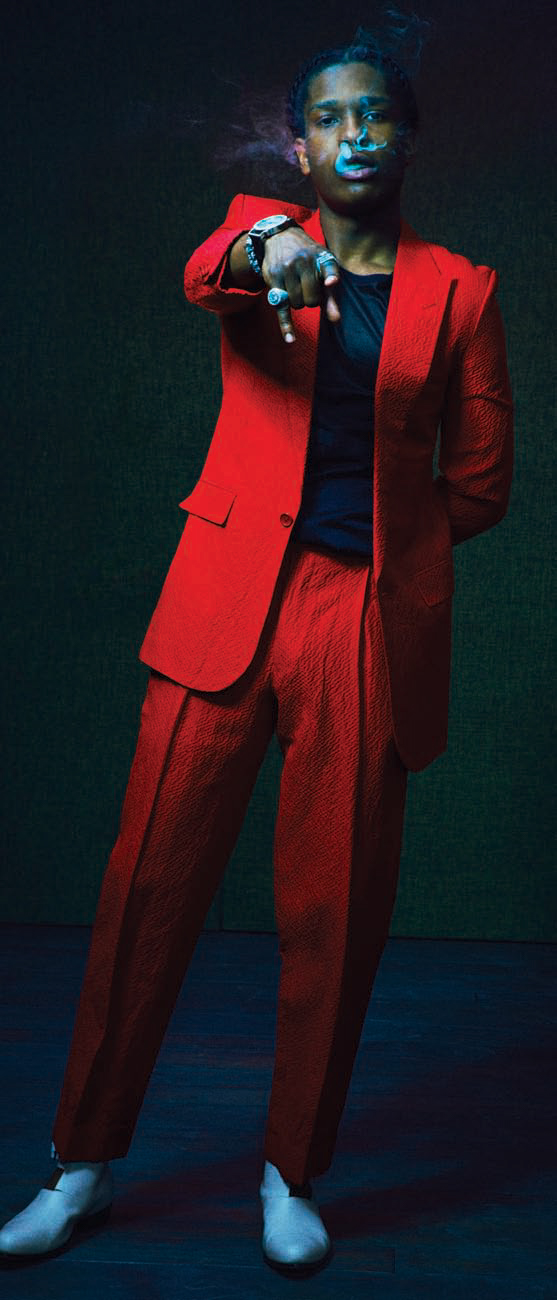

Today we see next-wave artists such as A$AP Rocky of A$AP Mob and the GHE20GOTH1K movement maintaining Harlem and the melting-pot Manhattan metropolis as an ongoing locus of politicized gender play. Rap’s self-proclaimed “pretty motherfucker,”12 A$AP Rocky, personifies the new Black dandy. Outfitted in cornrows and grill, his look is ghetto gorgeous and his voice Texas trill. He’s jiggy in Paris, suiting up for the cover of L’Uomo Vogue and still married to the mob. Much like Newsome, A$AP Rocky is the quintessential postmodern dandy riding high (and dirty!) through the sludge of our racist past. Although his lyrics often leave much to be desired, Rocky’s image and affect queer the dialogue of hip-hop so much that OG folks such as Uncle Murda feel the threat. “A$AP Rocky hotter than both y’all, yeah it’s niggas like that that’s fucking up the culture y’all,” rapped Murda in his recent Kendrick Lamar dis track “Control Response.” Cult legend MC Cunt Mafia, who threw the Brooklyn “Whorehouse” raves where an unheard-of Rocky used to perform, called Rocky’s look “quintessential gay male New York.”13

Rashaad Newsome, still from Five (Art Hong Kong), 2011, video [images courtesy of the artist]

Newsome is coincidentally hailed as the man who introduced the “art world” to Rocky’s crew, A$AP Mob. At a W magazine party celebrating the publication of several new works by Newsome, the pristine SoHo gallery space was allegedly “thickly clouded” by marijuana smoke preceding a surprise performance by mobsters A$AP NY-Nast and A$AP Ferg. Lacking the appropriate terminology to describe what happened, given the cultural impulse to disassociate hip-hop from “Art,” writer Ramya Velury called the event “a discotheque and not an art exhibit.”14 A$AP Ferg told the press, “We’re doing this here for Rashaad.”15

Rocky uttered a similar explanation as to why he appeared as a runway model at the launch of gay designer Shayne Oliver’s “apocalyptic streetwear” collection Hood By Air. “I just wanted to support … what Shayne is doing,” Rocky said, no matter that he couldn’t tell whether many of the models were “guy or … girl.”16 Characterized by a dramatic fusion of street wear and goth, from Kanye-esque kilts to steezy high-end hoodies with bold clean lettering, Oliver’s brand, largely through Rocky’s endorsement, has quickly begun to define the style of a generation of youth who are very comfortable with the flamboyant. Some would even call it a type of (r)evolution.

Rashaad Newsome, still from Untitled, 2008, silent single-channel video with sound, 8:07 minutes

The GHE20GOTH1K (pronounced “Ghetto Gothic”) movement, headed by Shayne Oliver and DJ Venus X, is a multiracial, queer, pansexual underground space integrating fashion forefronters, ghetto kids, feminists, hip-hoppers, goths, and (Afro)punks. On Halloween 2013 I encountered Oliver, dressed as Nicki Minaj, at one of the GHE20GOTH1K raves where he softly mentioned that the clothing line was now “full time.”17

At GHE20GOTH1K raves today’s youth run ratchet with yesterday’s epithets and commit once-suicidal fashion maneuvers. These are spaces where voguing, hip-hop, and breakdancing collide in the wake of influential icons, including Newsome, who have made cultural bricolage a brave new order. If only cultural mash-up happened on a level playing field. GHE20GOTH1K no longer admits photographers because of the rapid speed with which corporations scoop up underground styles and harness big budgets to market them as their own overnight.18

In many ways Newsome’s work heightens the stakes of a culture in which the historic spectacularization of the Black body often serves to hoodwink foul economic inequalities.19 Hip-hop in many ways still buttresses a White male corporate power structure, as does art, often at the expense of marginalized virtuosos who become the show ponies of the 1%. For the majority of Black males, making even a modest income from one’s creative labor is a fairy tale measured against the threat of the prison industrial complex (PIC). A for-profit business herding Black and Latino youth out of high schools and behind bars, PIC’s enforced gender segregation largely determines the aesthetic queering of gender boundaries (cornrows and saggy pants) we associate with hip-hop’s subversive style.

Which is very much why Newsome’s fierce visions of queer Black power and prestige sound a tender high note within the quotidian art milieu. Trading marginality for majesty, Newsome fuses ghetto glam and noble chic, lowercase vogue and uppercase Vogue. His work dissolves the standards by which we judge social position, terms that are always deeply seeped with racial, sexual, and class connotations.

A$AP Rocky from L’Uomo Vogue fashion shoot [photo: Francesco Carrozzini;o courtesy of Francesco Carrozzini / Trunk Archive]

This feature originally appeared in ART PAPERS January/February 2014, guest-edited by Fahamu Pecou.

References

| ↑1 | Monica L. Miller, Slaves to Fashion: Black Dandyism and the styling of Black Diasporic Identity (Durham, NC: Duke UP, 2009), 10. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Rashaad Newsome quoted in Rozalia Jovanovic, “Rashaad Newsome’s Hip Hop Heraldry,” Flavorwire, May 6, 2011, http:/flavorwire.com/176992/Rashaad-newsomes-hip-hop-heraldry |

| ↑3 | Miller, 1. |

| ↑4 | James Scott quoted in Miller, 15. |

| ↑5 | Miller, 3. |

| ↑6 | Miller, 99. |

| ↑7 | Priscilla Frank, Rashaad Newsome’s King Of Arms’ Comes to New Orleans Museum Of Art,” The Huffington Post, June 20, 2013, www.huffington.com/2013/06/20/rashaad-newsome-king-of-arms-new-orleans_n_3461114/html |

| ↑8 | Melena Ryzik, “Blending Hip-Hop and Heraldry,” The New York Times, October 20, 2011, wwwnytimes.com/2011/10/23/arts/design/Rashaad-newsome-blending-hip-hop-and-heraldry.html |

| ↑9 | Miller, 178. |

| ↑10 | Miller, 22. |

| ↑11 | “On Seventh Avenue,” Baltimore Afro-American, December 27,1930, quoted in George Chauncey, Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Making of the Gay male World, 1890-1940 (New York: Basic Books, 1994), 244. |

| ↑12 | A$AP Rocky, “Wassup,” Live, love A$AP, 2011. |

| ↑13 | Cunt Mafia interview by Katie Cercone, July 31,2013, Brooklyn, NY. |

| ↑14 | Ramya Velury, “Marlborough Chelsea Celebrates Rashaad Newsome Debut in W Magazine,” June 6,2012, guestofaguest.com/new-york/events/Marlborough-chelsa-celbrates-rashaad-newsome-debut-in-w-magazine |

| ↑15 | Michael H. Miller, “Rashaad Newsome Introduces the art World to A$A4 Mob, June 6, 2012, www.galleristny.com/2012/06/rashaad-newsome-introduces-the-art-world-too-app-mob |

| ↑16 | A$AP Rocky quoted in Nate Erickson, “Celeb Spotting: A$AP Rocky Closes Hood by Air Fall 2013,” GQ, February 10,2013, www.gq.com/fashion-shows/blogs/fashion-week/2013/02/celeb-spotting-aap-rocky-closes-hood-by-air-fall-2014.html |

| ↑17 | Shayne Oliver, conversation with author, GHE20GOTH1K rave in Bushwick, Brooklyn, October 31, 2011. |

| ↑18 | Misty White Sidell, “GHE20GOTH1K Party Initiates New Fashion Trend,” The Daily Beast, April1, 2013, www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2013/04/11/ghe20-goth1k-party-initiates-new-fashion-trend.html |

| ↑19 | Miller, 48. |