Essex Hemphill: Take Care of Your Blessings

Isaac Julien, Pas de Deux No. 2 (Looking for Langston Vintage Series), 1989/2016, Ilford classic silver gelatin fine art paper, mounted on aluminum, 22 7/8 x 29 3/8 inches [courtesy of the artist, Jessica Silverman Gallery and The Beth and Richard Marcus Collection]

Share:

Scale is often used as a metric of significance. For viewers eager to be emersed in proclamations of artistic genius, an exhibition’s square footage can be read as a greater investment of funds, labor, or time. An exhibition’s significance could be ill determined by the intricacies of its design, the flash of graphics, the heft of a printed catalogue, all of which signal a cultural institution’s level of investment in an artist or artists, in a period or movement, in cultures or civilizations. Poet, performer, and activist Essex Hemphill (1957–1995) graced this earth for only a short time, but in that time, he became one of the most influential Black and queer voices of his generation, and arguably of the 20th century. Essex Hemphill: Take Care of Your Blessings, at the Phillips Collection, was curated by associate curator Camille Brown. This summer exhibition did not rely upon scale to emphasize Hemphill’s importance. Instead, it made that argument with a simple and effective display of Hemphill’s “living impact” by placing his words and image amid the works of a focused, multigenerational group of visual artists whom he inspired.

Hemphill was primarily an autobiographical poet. He wrote and performed poetry at the intersections of his identities, publishing and performing words about exclusion, fetish, heartbreak, sex, and love. The exhibition’s title harks back to his advice to his readers to nourish their gifts, their innate talents, as God given. These words resonate as a gentle call to action from Hemphill and the Phillips, particularly in this political climate, when artists and scholars are pressured by an increasingly fascist government to censor themselves and their work. Take Care was installed in two small galleries on the third floor of the museum. People familiar with the Phillips Collection may recall the upper-level annex that connects the original 1897 Phillips to its 2006 expansion. Regardless of the factors that led to the selection of these particular galleries, the conceptual vision was strengthened by the seemingly modest location. The galleries can be entered from either building—bridging the old and new—disrupting the potential for singular narrative experience. The artworks were not installed in any legible order and were interspersed with cases of printed ephemera. Viewers were empowered to navigate the space and engage works of interest from either direction, much like the way that Hemphill and his collaborators would perform verses—top to bottom, bottom to top.

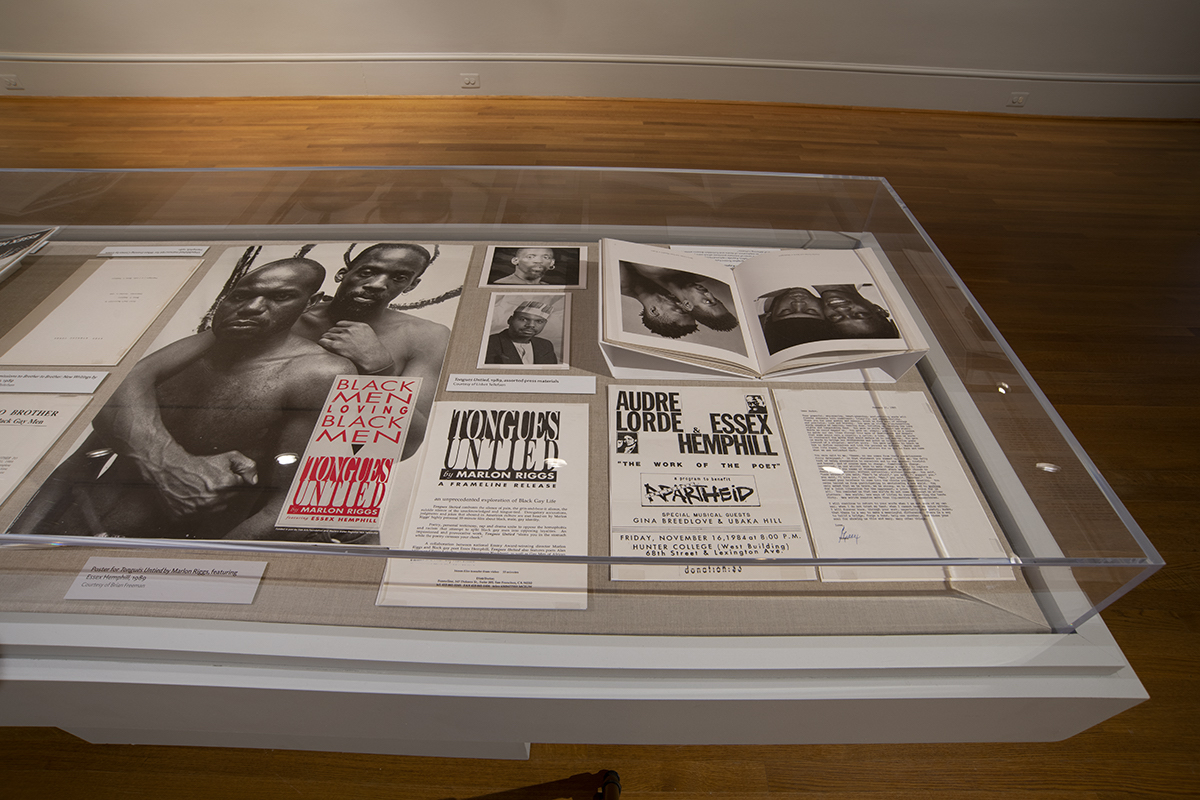

Essex Hemphill: Take Care of Your Blessings, installation view, 2025 [photo: Lee Stalworth; courtesy of the artist and the Phillips Collection, Washington D.C.]

Take Care offered no biographical narrative of Hemphill’s life, an approach that can often narrow the life of a gay person who died of AIDS-related complications merely to their battle with the virus. Instead, the exhibition presented a slice of his community and career in Washington, DC, where he was most active and vibrant. At one entrance, a large projection plays footage from a panel at CLAGS’ Black Nations/Queer Nation? conference, which was held at the CUNY Graduate Center in 1995, the year Hemphill died. He sits beside author Samuel R. Delany and interdisciplinary scholar Coco Fusco, igniting the room with his poetic prose and proclamation that “racism doesn’t go better with a big dick, or a hot pussy, or a royal lineage.” Viewers entering this space were immersed in the seductive sound of Hemphill’s voice as it resounded throughout the galleries—at times quick with humor, at others heavy with mourning. His words washed over the visual art and ephemera and intermingled with them. Where his image was included in the exhibition, he almost always appeared amid his communities—collaborators, lovers, interlocutors, friends. Only one framed portrait of Hemphill by lens-based-artist Lyle Ashton Haris presented the poet seemingly alone, although the purse of his lips and the unashed cigarette between his fingers suggest a loved one behind the camera, dishing the buzz.

Lyle Ashton Harris, Essex Hemphill, LA Contemporary Exhibitions, Los Angeles, 1992, chromogenic print, printed 2025, 15 x 20 15/16 inches [© Lyle Ashton Harris; courtesy of the artist and the Phillips Collection, Washington D.C]

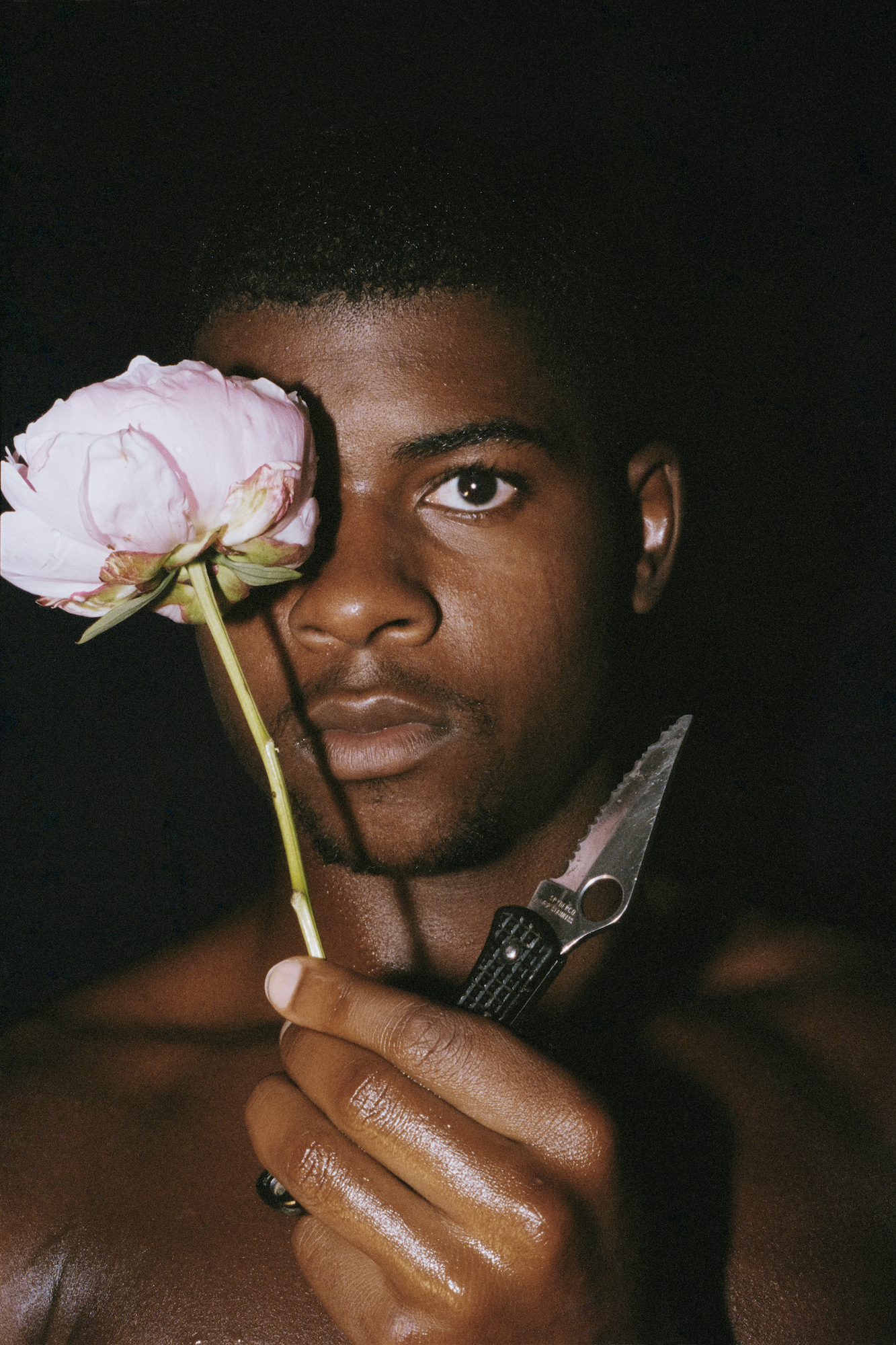

The included artists’ magnitude was downplayed in the exhibition, and it may even have been lost on those viewers less versed in contemporary art. Established and canonized artists, such as Lyle Ashton Harris, Glenn Ligon, and Isaac Julien—Hemphill’s contemporaries—were placed in a nonhierarchical visual dialogue with such critically acclaimed artists as Tiona Nekkia McClodden, Clifford Prince King, and Diedrick Brackens, who represent a rising generation of Black queer artists. The exhibition could easily have relied upon the individual fame of each featured artist, or could have included other well-known Black queer artists, such as Kehinde Wiley, Mickalene Thomas, or Julie Mehretu to further emphasize Hemphill’s relevance—and thereby bolster the exhibition’s profile. Each of the included artworks—made at various points in the artists’ careers—directly evoked or alluded to Hemphill’s practice by taking titles from his poems, influence from his activism, or, in the case of Julien’s 1989 film Portrait in Blue: Essex Hemphill, documentary footage of the poet himself shot in Super8 black and white. This curatorial gesture exemplified Hemphill’s “living impact” across several generations.

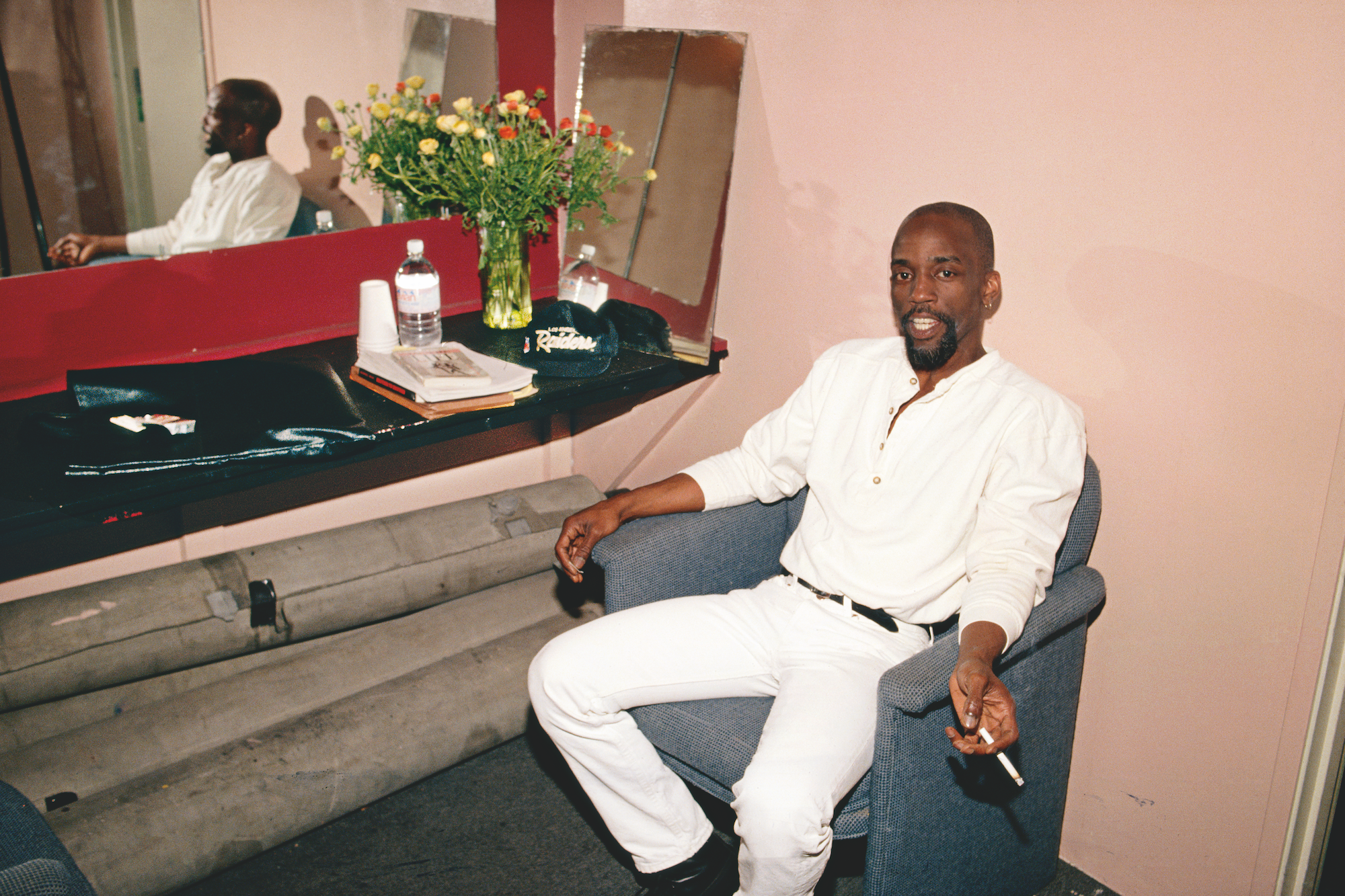

Clifford Prince King, Conditions, 2018, chromogenic print, 24 x 16 inches [courtesy of the artist, Gordon Robichaux, NY and STARS, Los Angeles]

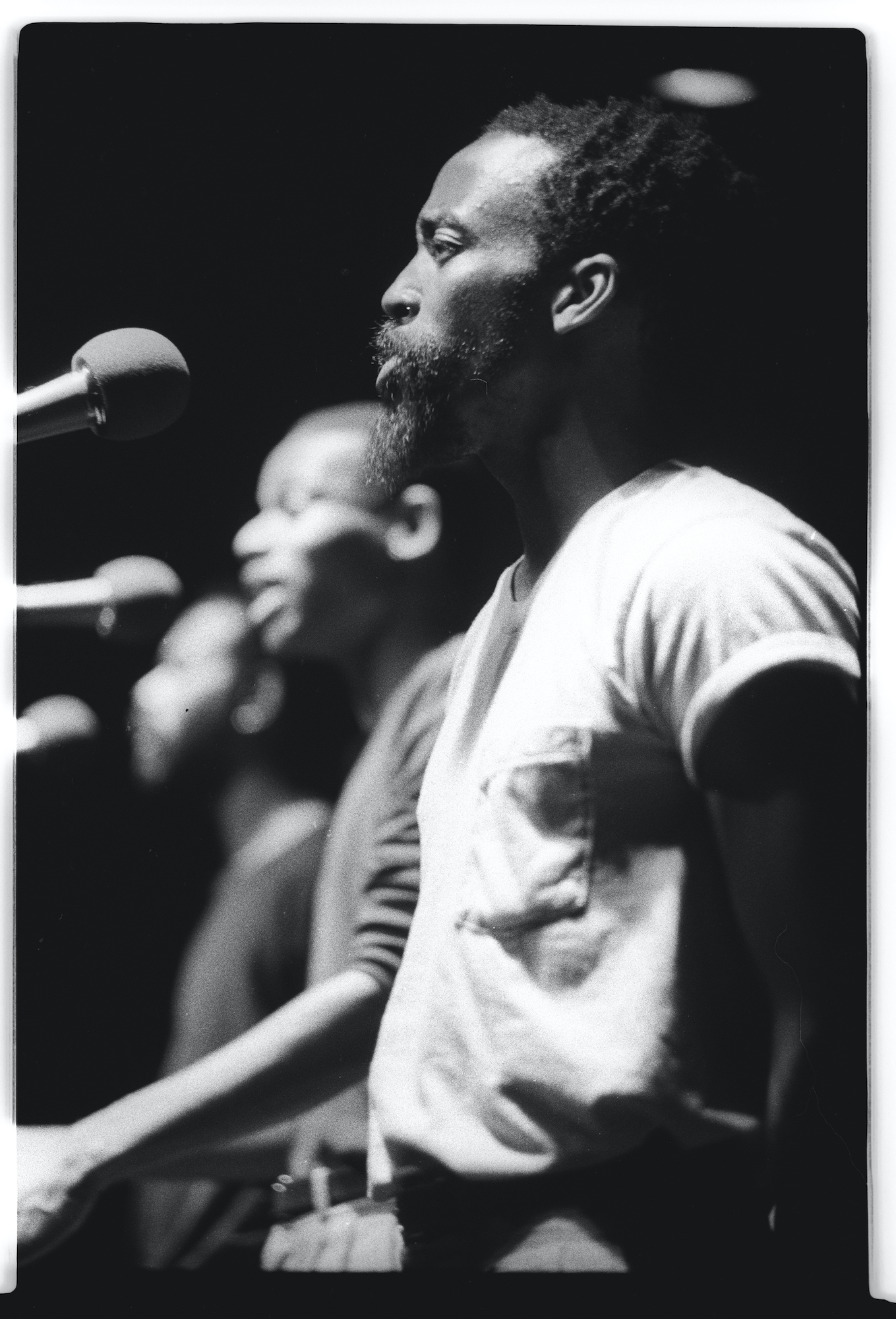

Wayson Jones, left, Chris Prince, and Essex Hemphill do performance poetry in Saturday, May 31, 1986 at D.C. Space in Washington [photo: Sharon Farmer/sfphotoworks]

The inclusion of Richard Bruce Nugent’s watercolor Smoke Lillis and Jade (c. 1925) brilliantly positions Hemphill at the center of a much older and more historicized lineage of Black queer cultural production. Nugent (1906–1987) was an openly gay writer and artist known for bridging queer narratives of the Harlem Renaissance era with the Black gay movement of the 1980s, to which Hemphill belonged. Viewers versed in the histories of queer creatives could trace multigenerational connections and influences across the galleries. Langston Hughes’ “The Weary Blues” comes to life in filmmaker Isaac Julien’s biographical explorations. In Julien’s 1989 film Looking for Langston, in which Hemphill and Nugent’s words are featured, you can see Julien’s influence on the visual poetics of Shikeith’s photographs. Hemphill’s bold and poetic approach to relating his personal experience of living with a fatal illness was represented through collaborations with such contemporaries as Audre Lorde, and that influence can be seen in the contemporary visual storytelling of Clifford Prince King’s photographs and installations. As a bridge between generations, Hemphill carries queer Black narratives to the present generation of poets including Jericho Brown, Danez Smith, and such visual artists as Rotimi Fani-Kayode, Jonathan Lyndon Chase, Paul Mpagi Sepuya, and countless others.

Isaac Julien, Pas de Deux No. 2 (Looking for Langston Vintage Series), 1989/2016, Ilford classic silver gelatin fine art paper, mounted on aluminum, 22 7/8 x 29 3/8 inches [courtesy of the artist, Jessica Silverman Gallery and The Beth and Richard Marcus Collection]

The subtle power of Take Care of Your Blessings was in how it revealed the potential of the museum exhibition as a tool to explore and honor our Black queer ancestors. Unlike other recent biographical exhibitions, such as Edges of Ailey at the Whitney or Alice Coltrane, Monument Eternal at the Hammer, both of which relied upon magnitude and elaborate design to make “icons” of Coltrane and Ailey, Take Care presents Hemphill as a radically vulnerable human being, a powerful poet and performer, and as a member of intricate communities of artists and activists. Hemphill was not presented as a genius or as a singular progenitor of any movement. Instead, he was presented as a conduit, as a culture bearer, and as an unyielding source of inspiration. As writer and curator Hilton Als has demonstrated, again and again, with his exhibition series highlighting the artistic contributions of such figures as Toni Morrison, James Baldwin, and Joan Didion, for an exhibition to resonate true, it must center the person, not as an icon but as the human being behind the words.

I refer to the influence of Essex Hemphill as “living” because it continues to grow stronger as time goes on despite various systemic attempts to erase or commodify radical Black queer voices. Hemphill’s 1992 collection, Ceremonies: Prose and Poetry had a limited print and no subsequent editions. Despite being his largest and most celebrated book, the remaining copies are now considered rare and precious. In the decades since his death in 1995, his publications have been primarily accessible in archives, through the reverential works of other multimedia artists, or through fugitive digital networks. As a spoken word poet and performer for live audiences, his digital footprint was also limited, making his appearances in documentaries such as Rodney Evans’ 1994 Black is… Black Ain’t a significant representation of how he collaborated with other creatives across platforms. The 2025 publication of Love Is a Dangerous Word: The Selected Poems of Essex Hemphill and the exhibition’s catalogue present new opportunities for his work to continue influencing new generations.

In essence, Hemphill is our blessing. His legacy is ours to tend. His work carries the voices of a lost generation into the present for us to reckon with. He shouted at us to love, fuck, and protect one another. The phrase “you can’t see the forest for the trees” describes someone who is so singularly focused that they fail to recognize the bigger picture. Hemphill demonstrates how the queer artist, within a community, does not simply die. They are our mother logs, the fallen trees that, through decay, help nurture the ecosystem of a new forest. He laid bare the truths of a brief life and made fertile ground from which an incalculable number of artists and writers would grow.

Diedrick Brackens, the night is my shepherd, 2022, cotton and acrylic yarn, 84 x 82 inches [courtesy of the artist, the Rubell Collection, Miami and Washington, DC]

TK Smith is a curator, writer, and cultural historian. His interdisciplinary research engages materiality to analyze art, identity, and culture. As a public scholar, he serves as a conduit between artists, ideas, and communities to produce thoughtful exhibitions, publications, and programs. He currently works as curator, Arts of Africa and the African Diaspora, at the Michael C. Carlos Museum at Emory University. Smith’s writing has been published in exhibition catalogues, academic journals, and periodicals, including ART PAPERS, where he is a contributing editor. In 2022, he was awarded an Andy Warhol Writers Grant, and in 2024 he won a Leo and Dorothea Rabkin Prize. He has been a visiting lecturer at numerous academic and cultural institutions, including Cornell University, where he taught undergraduate courses on cultural criticism. Smith is a doctoral candidate in the History of American Civilization program at the University of Delaware, where he is completing his dissertation, Granite, Power, and Piss: The Transformation of a Confederate Symbol.