Erasing Pronouns: Beatriz Santiago Muñoz’s Ottilia

Beatriz Santiago Muñoz, Oriana, 2023, multichannel video installation, 16mm film and 4K video, 5.1 sound, 27’00’’ [photo: by Aurélien Mole; courtesy of the artist and CRAC Alsace]

Share:

The women say that of her song nothing is to be heard but a continuous O. That is why this song evokes for them, like everything that recalls the O, the zero or the circle, the vulval ring.

– Monique Wittig, Les Guérillères

Beatriz Santiago Muñoz brings us to Year Zero at CRAC Alsace, with all the violence, cleansing, and rebirth implied. Set in the rainforests of Puerto Rico—the artist’s home—a lush series of films shows a band of women warriors as they worship, tell stories, mourn, and heal. This narrative is not foreign to Muñoz’ practice, but these balmy narratives in particular have their origin in Alsace. For more than five years, curator Elfi Turpin has actively disseminated the texts of the radical lesbian writer Monique Wittig, who was born in 1935, not far from the CRAC Alsace, in Dannemarie. As Turpin puts it Wittig “is part of the art center’s political and affective territory.” At Turpin’s instigation, local artists, teachers, and students read Wittig’s work—including her 1969 novel Les Guérillères, which is a utopian yet apocalyptic story about the overthrow of patriarchy, and the resulting sexless society. Muñoz chose to dramatize Les Guérillères in her multi-part, multi-channel film Oriana (2023), in which fellow artists and activists appear as performers. She then expanded upon Turpin’s local educational project in the films Oenanthe and Conversation (both 2023) with Alsatian women as participants. During both stages of the project, Les Guérillères was used as the guide—or, to use Wittig’s term, the Feminary—that the artist and performers employed as a source of reflection, action, and dialogue. As one proceeds through the eight screening rooms of the art center, this complicated network of relationships between texts, locales, and populations is not obvious. What does emerge, with immense power, is the story of a sexless world—though not necessarily a feminine one, which is noteworthy, as no men appear in the films—and the unity of women in an unpredictable and dangerous environment.

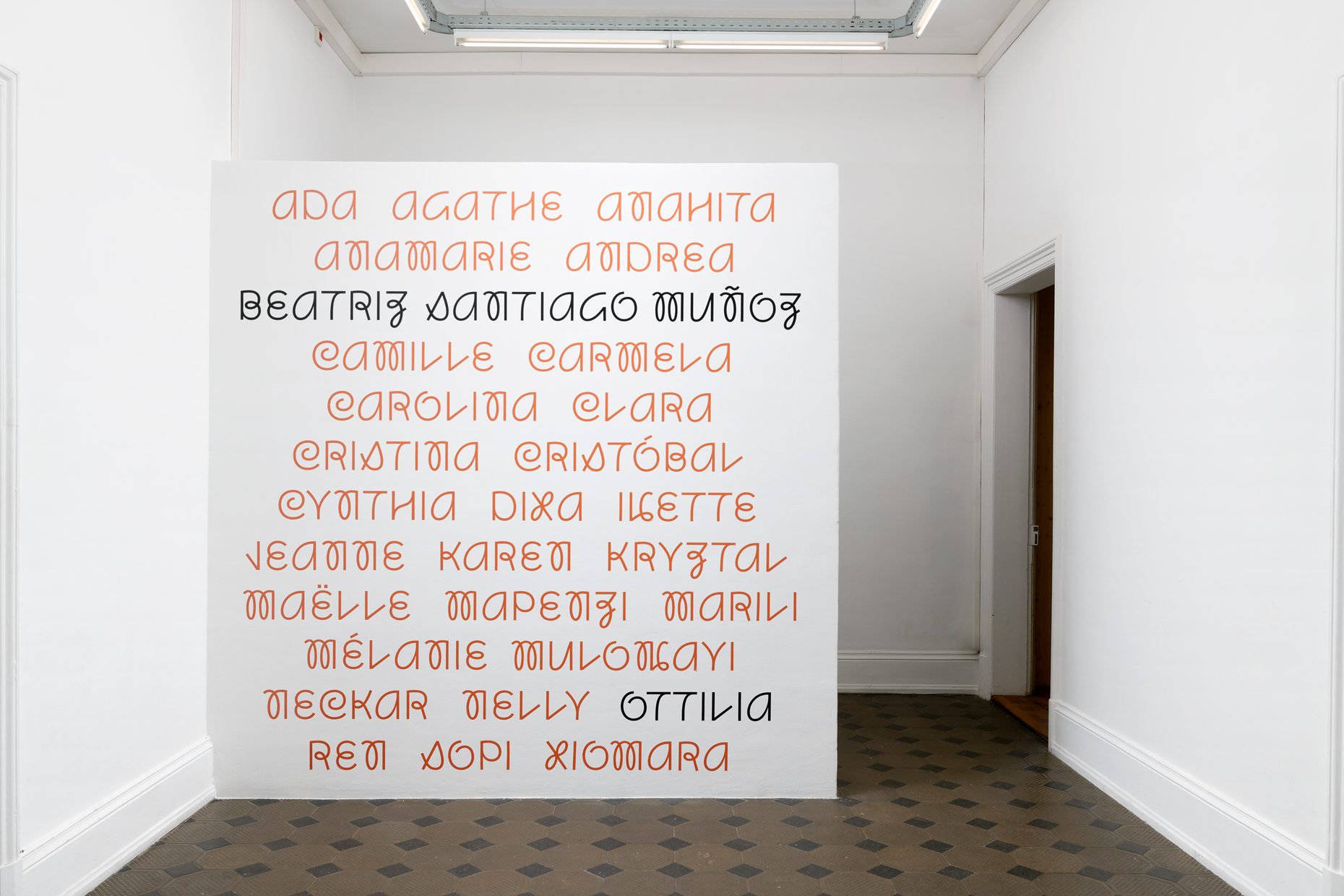

Beatriz Santiago Muñoz, OTTILIA, installation view, 2023 [photo: Aurélien Mole; courtesy of the artist and CRAC Alsace]

Witting erases sex in Les Guérillères by starting at the foundations of text, with pronouns, and Muñoz realizes the ingenuity of this strategy. Because text, according to Wittig, is an invention of patriarchy, then it must be deconstructed from the bottom up: women using text are already engaging in a structure weighted toward the patriarchal. A partial solution comes through names’—women’s names, but also those of flora and fauna—genderless specificity. Muñoz accomplishes this feat in the dialogue of Oriana by simply reproducing the long lists of plant names that appear in spells and healing potions in Les Guérillères, as well as the recitation of mythologies centering women protagonists. Visually, the artist overwhelms us with fecund detail and close-up shots of berries, hands, machetes, faces, and flowers, many of which are simultaneously named as we watch. This process engenders a blanket equality—there are no primary characters or protagonists. Different scenes of Oriana and Oenanthe play out in various rooms of the CRAC Alsace. In Oriana, scenes are focused on activities: women wash and relax, tell stories around a bonfire, chop thick bamboo stems, prepare a flower-bedecked woman for death, and perform a ritual in a cave. As in Les Guérillères, the action never rests on the shoulders of an individual but on those of the group. The tools they use betray some temporal relation to the present, but the action seems to be out of any specific time frame (like in Wittig’s novel—ominously in the future is all one can conclude). Oenanthe is similarly broken into two rooms, but like Conversation, it takes place in the present, in Alsace, and references real places and histories.

Beatriz Santiago Muñoz, Figure on hammock,, 2023, Overalls, palm bark fiber mask, glazed ceramic leg [photo: by Aurélien Mole; courtesy of the artist and CRAC Alsace]

Charles Mazé & Coline Sunier, Flags at CRAC Entrance, 2023 [photo: Aurélien Mole; courtesy of the Beatriz Santiago Muñoz and CRAC Alsace]

Thus, the notion of the circle—the O—makes sense. The nine rooms of Crac Alsace and its entry hall are activated not only by films projected on screens, but also by various objects that unite all sides of the story. Muñoz interweaves the humid and threatening rainforests of Finca la Perla in Puerto Rico, the deciduous greenery of Alsace, the shore of the lake of Dannemarie, and the spaces of the art center itself. The rainforests are as alive with life as they are with death, as is the demesne of Muñoz/Wittig’s band of women warriors, all evoking a timeless, wet state of nature. One iteration of Oenanthe documents young women in CRAC Alsace’s printing studio, looking at books and producing prints, but also discussing the history of women’s labor in the region; another scene documents young women singing and exchanging riddles on the lakeshore. In between the two screening rooms, visitors pass through a room with textile, bark, and ceramic masks, forcing them to recalibrate their sensitivity back to the realm of Oriana—and so the circle closes. On the ground floor, a similar sleight-of-hand is employed. Through a peephole in the wall, one can see into a room where one scene from Oriana plays—a scene in which warriors handle instruments of ritual or magic: magnifying glasses, eggs, a knife.

In the adjacent room, the film Conversation presents a group of contemporary Alsatian women who discuss Mittika Ingrimm zur Unruhe ou Blanche Colère du dechaînment ou (date unknown), a work of art by Lena Vandrey that hangs in the gallery. Vandrey (1941–2018) was a friend and contemporary of Wittig’s and created a series of imaginary portraits drawn from Les Guérillères.

Entrance wall designed by Charles Mazé & Coline Sunier, 2023 [photo: Aurélien Mole; courtesy of the Beatriz Santiago Muñoz and CRAC Alsace]

Inside the entry hall of CRAC Alsace, Muñoz highlights the names of the performers in the films with size and gravity equal to her own (with the exception that their names appear in black, hers in red). Placing the artist on an equal playing field with her subject would likely have pleased Wittig. Throughout Les Guérillères, a list of women’s names disrupts the text, emphasizing the importance of the group above the action of the story. Only one other name appears, like the artist’s, in black and that is St. Ottilia, whom the artist presents as a historical counterweight to Wittig. Ottilia, or Odile, is the patron saint of the blind and visually impaired—and of Alsace. As a saint and healer, she completes the circle between filmmaker and writer, Alsace and Puerto Rico, and Wittig’s idea of an atextual equality that can be heard and felt, but not read.

Will Corwin is a sculptor and journalist from New York. He has exhibited at Clocktower, La MaMa Galleria, and Geary gallery in New York, as well as in London, Hamburg, Beijing, and Taipei. He writes regularly for ART PAPERS, The Brooklyn Rail, BOMB, artcritical, and Canvas—and formerly for Frieze.