Editors’ Dialogue: A Chorus of Positions With a Kinship of Aims

Share:

To reflect the collaborative nature of this issue, the usual editor’s letter takes the form of a colloquy.

Sarah Higgins: So here we are, after many Zoom conversations over the past few months, ready to have a more formal one about this issue, which we co-edited. The original idea for the theme was “enacting politics,” a phrase I brought to you as a starting point. What I thought was most productive about that prompt was that it made you think of several case studies that we could discuss.

Stephanie Bailey: Right. The idea was to think about practices that use the art world as a functional tool for actual intervention and rerouting; for example, as a network through which capital can be redistributed, whether attention capital or economic capital. We thought about artists like Theaster Gates, Lauren Halsey, Zanele Muholi, Teresa Margolles—even Christoph Büchel’s Barca Nostra, Banksy’s Dismaland, or Renzo Martens’ White Cube.

We were thinking: What practices transcend, break, or breach that line of representing politics in an art world that so often enables the representation of politics but doesn’t necessarily seek to take those politics further? From that initial brainstorm came the idea of “gaming the system,” which, in the context of the arts, recognizes its systems and networks as a space of utility.

SH: We found that we were both interested in a particular type of intervention, one that could take place from within a power dynamic in which disempowered groups or individuals could take advantage of various methods: hijacking, hacking, or inhabiting, for example. I think that that’s where gaming emerged as a method of subversion that we wanted to explore. When we arrived at that one, we were both, like, “Yes! That’s it!” The goal with “gaming” was to approach the idea in a way that refuses to be reductive, but that remains intentionally approachable. I think we have all, at one time or another, gamed a system. It’s such a relatable way of addressing power: to game the structure that you are being put beneath.

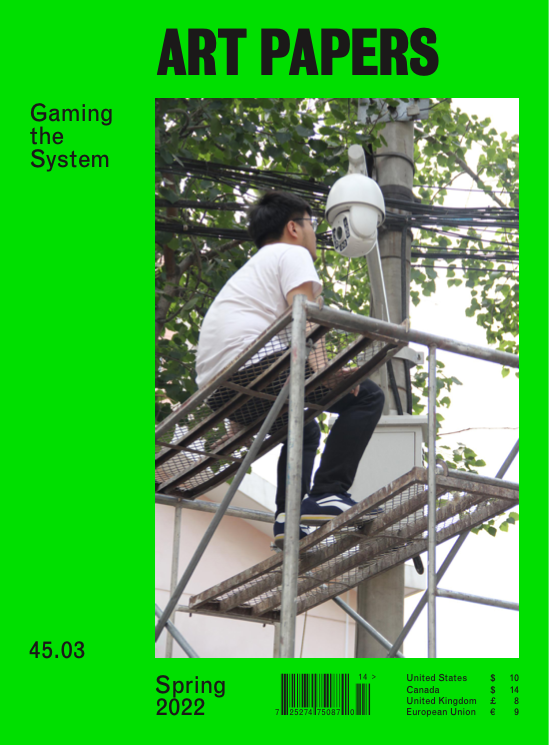

SB: Yes, it’s a way of breaking through that critical cul-de-sac that can so often be found in the arts, when attempts at subversion are shot down, purely because of the context in which the subversion is staged. In the issue, one example comes from Chinese artist Ge Yulu, who talks about effectively playing with China’s political conditions in Cutting In: Dances with the State and the Collective. Another comes from Khaled Malas, who talks about his work with Sigil, a collective that actively used the art world to fund projects which would have a direct impact on communities in Syria amid the devastation of the war. Gaming a system often means playing with the rules that define it, and then seeing how far you can push the line or reroute it to further your own cause.

This idea of rerouting also defines transdisciplinary alliances that have used the art world’s infrastructures to extend and network activist movements, such as Jonas Staal and Radha D’Souza’s Court for Intergenerational Climate Crimes, which they discuss in Indicting the Poisonous Imaginary; and War Inna Babylon, an exhibition-slash-indictment staged at London’s ICA, which is introduced here through a roundtable with Tottenham Rights co-founder Stafford Scott, Kamara Scott, Abi Wright, and Forensic Architecture’s Eyal Weizman. Both conversations show how art can and does have a use function when it goes outside of its echo chamber—all while recognizing the issues and contradictions therein.

SH: It’s important to point out how the conversation format became a central part of this issue, one that we hoped would respond to a type of position fatigue that we both have felt, and that often feels counterproductive. We wanted to sideline the presumption that one must begin by taking a position. It’s not that we don’t have a position, but we wanted to instead hold space for many positions in order to articulate a perspective that can be enacted from a variety of angles, from a variety of relations to the institutions of art.

There’s a spectrum in these positions, one that ranges from how to make a broken system more productive, to working around the system, to creating alternative systems. Lauren Tate Baeza’s conversation with Vitshois Mwilambwe Bondo addresses the question of what to do with a broken arts system that doesn’t serve its community—in this context, that of Kinshasa, where institutions tend to participate in spaces of power and prestige that many of the city’s artists have chosen not to engage. Rather than being stalemated by limited alternatives in the institutional landscape, they’ve created support structures, spaces, and modes of collective funding that work.

Then there is Jemma Desai’s essay “What do we want from each other after we have told our stories,” which whispers abolition and points to the question: What if we say no?

SB: Right. The format of this issue convenes around that question, too, as a gathering of people finding ways to say no, to act otherwise, and to share their experiences in practice. This idea of learning about ways of working through these pages brought to mind the Whole Earth Catalog as a kind of information-sharing platform.

SH: Yes, I brought it up, predictably, because the Whole Earth Catalog, as a toolkit, has always been influential for me when thinking about what print can do. I often seek to emulate that model with ART PAPERS, to create a chorus of positions with a kinship of aims—maybe not the same aims, but aims that are co-supportive of one another.

SB: “A chorus of positions with a kinship of aims” feels like the real title of this issue, which comes back to the decentering of positionality that recognizes the complex conditions in which people are working, and to which we’re both aligned and nonaligned. That’s why it was important to invite Rosanna Raymond to produce an artist project, and Shivanjani Lal to write this issue’s glossary.

Rosanna’s artist project, In.Vā.Tā.tion, introduces the Pacific Samoan concept of Vā, which Rosanna says is difficult to define because it is everything all at once. It’s such a potent word, because it describes a hyper-relational space that encapsulates all that is, was, and has ever been, right here and now. Shivanjani’s glossary introduces the Pacific term talanoa, which offers a beautiful way to navigate Vā: through mindful, curious, and open communication nurtured by a shared agreement to hold ground for expressions that might not align, but share a sense of commonality insofar as we are on this earth, together. As a Fijian–born woman of South Asian descent, Shivanjani’s glossary reveals a dialogue she is having with the term in a home that has welcomed her to feel it as her own, a place that her ancestors left behind, and a world she is moving in now—including the worlds she is extending her story to in these very pages, through talanoa.

SH: To me, Vā and talanoa also speak to the journey of co-editing this issue with you, and to something else that is important to the work we do at ART PAPERS: the emphasis of and rather than or. The embrace of hybridity, not as a debate intended to create a hierarchy of best practices, but as a gathering of many practices that reveals a multiplicity of perspectives, which themselves contain multiplicities. What emerges, ideally, is an idea that is complex and nuanced, familiar and foreign, accessible and challenging. Something that feels like the world.

Of course, we also have our reviews section, which I believe has a particularly close relationship to the theme in this issue. And, as always, we’ll expand and continue the conversation on ARTPAPERS.org.