Disappearing Into Motherhood

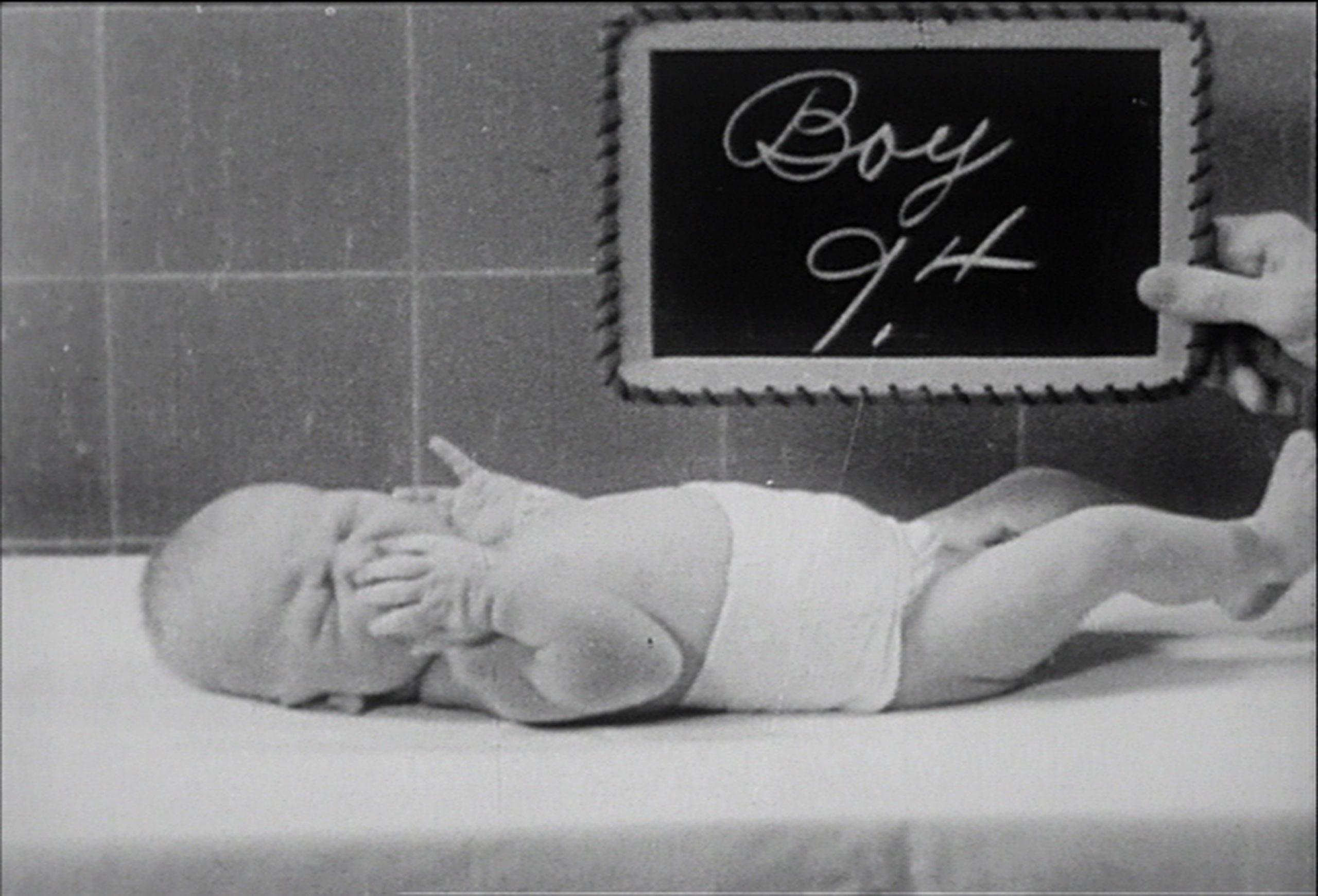

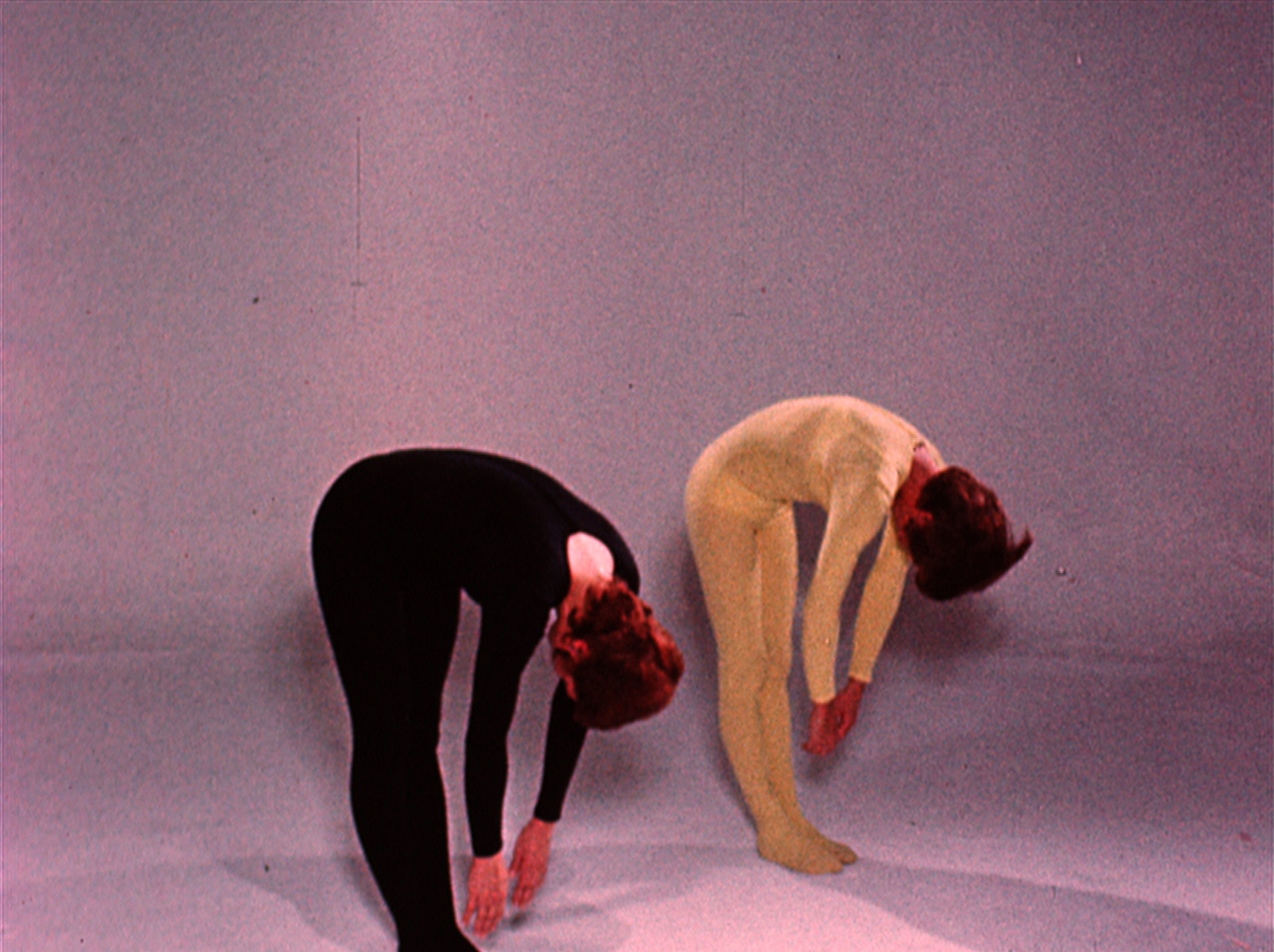

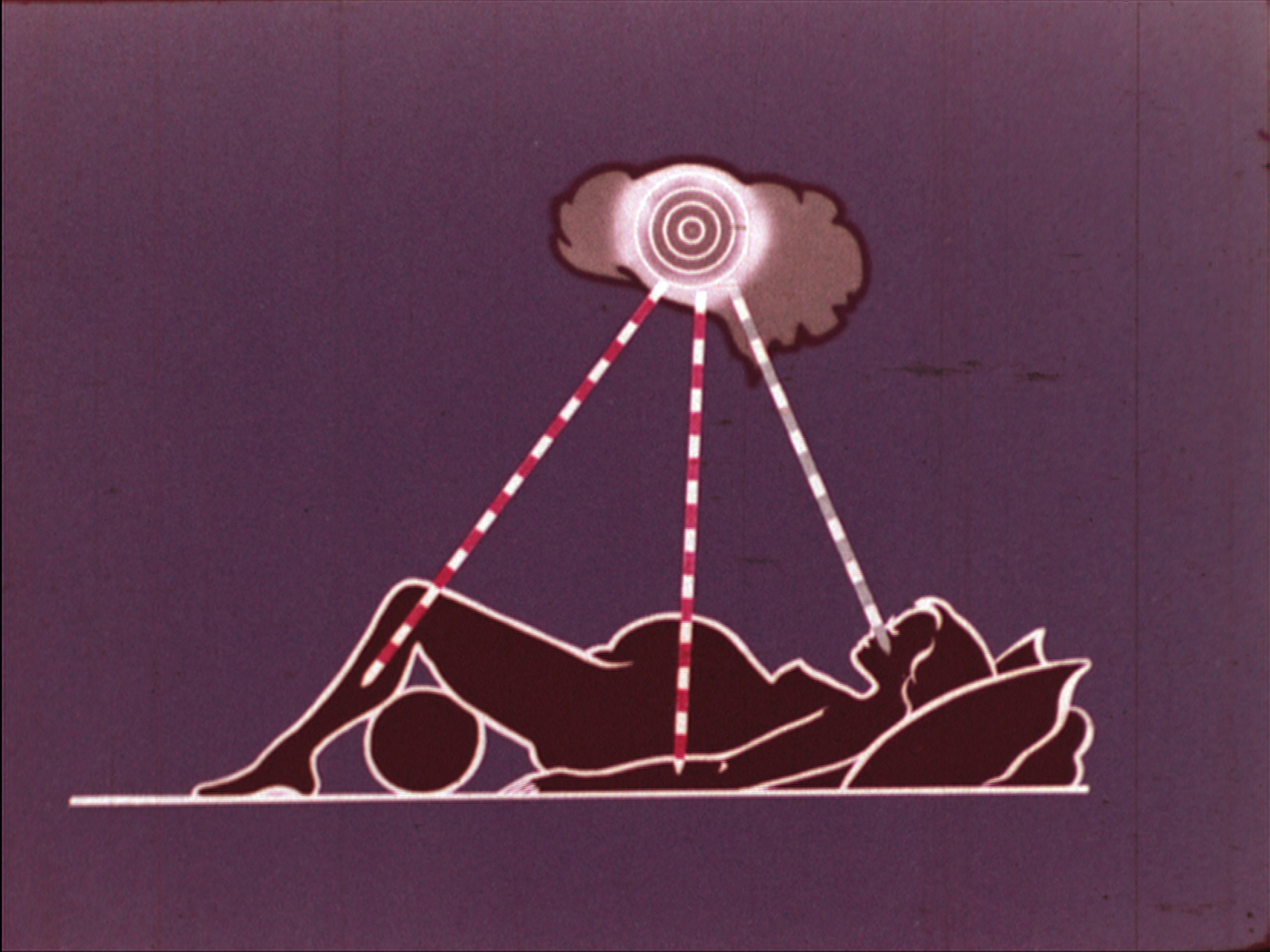

Irene Lusztig, “The Motherhood Archive,” (still), 91 minutes, 16 mm film, HD Video, and archival materials [courtesy of the artist]

Share:

I seldom talk about my private life with the various gallery dealers I know because I have sensed the subtle but pervasive stigma of motherhood among the old guard in the art world.

—Lenore Malen, “Forum: On Motherhood, Art, and Apple Pie”

In 1992, New York–based artists Susan Bee and Mira Schor published “Forum: On Motherhood, Art, and Apple Pie” in the journal M/E/A/N/I/N/G: Contemporary Art Issues.1 It consisted of written responses from 30 New York–based women artists, who not only disclosed the difficulties they faced as mothers in the art world but also shared the inspiring intersections between motherhood and artistic creation.

Bee, who was pregnant with her second child at that time, thought motherhood would be an interesting theme to explore as she observed that there was no space for mothers in the art world. She and her co-editor, Schor, had been producing the magazine since 1986, and they published a number of forums, wherein they invited artists, poets, curators, and critics to share their reflections on a specific issue. These various forums encompassed racism, feminism, resistance, artmaking and aesthetics, collaboration, privacy, trauma, and artists-as-activists, and were driven by an inclusive and political agenda to make visible under-represented perspectives on art.2

As Bee and Schor noted in their introduction, the process for this topic differed from those of other forums. Motherhood was so private—if not hidden—that the production process involved “an unusual bit of social detective work, in a pre-social networking era,” Schor recalls.3 Indeed, the editors, who navigated a pre-Internet social art world in New York, had to research whether the artists, who could fit the ethos of the magazine but didn’t belong to their immediate circle, happened to be mothers. Many women whom they eventually sent a questionnaire to responded with a lot of passion. Some expressed gratitude; some answered with vehemence and asked how the editors discovered they had a child. To Schor, this reaction “already indicated that among many women artists of that time who were mothers, motherhood was often kept fairly private or secret, for career reasons.” In many ways, Bee and Schor’s project revealed the taboo surrounding the topic of motherhood in the arts.

Irene Lusztig, “The Motherhood Archive,” (still), 91 minutes, 16 mm film, HD Video, and archival materials [courtesy of the artist]

People seem to take interest in the fact that I have an art career, jobs, and a family. They are interested in the nitty-gritty: When do I go grocery shopping? When do I go into the darkroom? In the same breath I am asked if I use cloth or disposable diapers and whether I prefer Kodak or Ilford photographic papers. When I teach, these types of questions surprisingly crop up often in the classroom. I am happy that young women ponder such issues because I see it as a sign of questioning the validity of those barriers that continue to confine women.

—Betty Lee, “Forum: On Motherhood, Art, and Apple Pie”

Forums have always played a crucial role in the Western history of women. These discourses served as tools and weapons to raise feminist consciousness among women in the 1970s.4 Bee and Schor’s 1992 version, the “Motherhood, Art, and Apple Pie” forum, had an impact in recognizing mothers’ marginalized and invisible position in the arts, and in building up a collective discourse from personal experiences, including Bee’s. As she recalled in a June 2020 interview, “Since I was, at that time, a young mother, having my first solo show of paintings at age 40 at the Virginia Lust Gallery in Soho, and with two small children, I was happy to know that other women had survived the experience and thrived. In retrospect, it was great that we were able to include Emma Amos, Nancy Spero, and Miriam Schapiro, and other artists who have since passed on.”

In that interview, Bee wrote to me, “Now the document we created seems of historic interest, and I know it has inspired other people to carry on this project.” Nowadays there exist various forms of forums and compilations available in print and on the Internet that contribute to making the subject of motherhood less fraught in the public,5 even though, as Schor suggested it to me, this visibility makes mothering neither less demanding nor less risky for artists’ careers. Bee added, “As a teacher, I have in the years since we did our forum, been approached by many women graduate students and asked, sotto voce, what my thoughts were about their having children. I think there is still a fear it might affect their ability to work and to have careers. To succeed in doing both still takes some financial means, a lot of help, and a very strong determination.” In the 1990s, women artists—as mothers or mothers-to-be—were in search of role models; they were looking for answers, and continuing interest in the M/E/A/N/I/N/G forum proved that they still are.

Irene Lusztig, “The Motherhood Archive,” (still), 91 minutes, 16 mm film, HD Video, and archival materials [courtesy of the artist]

Role models were nonexistent as far as I was concerned. Motherhood, the institution, the description of life in the language of patriarchs carried an ancient body of information—invisible—but deeply encoded in me and how tragic it was, that at that time I had no language for my dilemma. Centuries of prohibitions lay behind me and were mobilized against my wish to be both a mother and an artist at the same time.

—Miriam Schapiro, “Forum: On Motherhood, Art, and Apple Pie”

“Forum: On Motherhood, Art, and Apple Pie” set a precedent for how to present and understand motherhood in creative fields. When Moyra Davey included an excerpt from the forum in her iconic 2001 Mother Reader,6 she was captivated by the brevity and sharpness but also the “rueful humor and unexpected ironies” of the testimonials.7 By giving a platform to mother-artists and creating a dialogue about their conflicted positions and practices, Bee and Schor contributed a critical alternative framework for addressing parenting in the arts.

In 2021, Bee and Schor’s investigation into motherhood’s impact on artmaking feels more relevant and necessary as we grapple with the effects of the #MeToo movement and the Covid-19 pandemic, the latter of which exposed and reinforced the gender divide in domestic spaces.8 Their forum carved out a space for mothers, one where women could openly channel the ambivalence of parenting in contemporary Western societies,9 and particularly in the arts. The artists’ frank, direct, ironic—sometimes frustrated, angry, or totally distanced—testimonials don’t build a glamorous image of motherhood. Instead, the role remains ambiguous, messy, embedded in domestic and janitorial tasks, and it intersects many other demands: economic, social, cultural, and emotional. Building up role models for artist-mothers is to show what living and working looks like, what creating through multiple waves of pressure entails.

Irene Lusztig, “The Motherhood Archive,” (still), 91 minutes, 16 mm film, HD Video, and archival materials [courtesy of the artist]

I don’t know if being a mother changed my work, but it definitely has changed how my work is perceived and how it is made.

—Erika Rothenberg, “Forum: On Motherhood, Art, and Apple Pie”

Most importantly perhaps, the forum “Motherhood, Art, and Apple Pie” proves that parenting is not a dead end for artists. It is relevant here to highlight that Schor has, today, a slightly different story of how the forum came into being than Bee does. She remembers upsetting her co-editor, colleague, and friend by “expressing a fear that, with two children, Bee would ‘disappear’ into motherhood.” Schor did not have children, but like many of us who are parents or friends of parents, she could not ignore that mothering is, as Jessica Friedmann has suggested, a “fucking raw deal”10 that affects the practices of women, including artists, in expected and unexpected ways.

Starting from Schor’s anguished comment to pregnant Bee that she would “disappear into Motherhood,” the forum “Motherhood, Art, and Apple Pie” ended up demonstrating the creative outcomes of caregiving. The women shared ways that motherhood affected, transformed, and conditioned how they had been making and envisioning their art without stopping their making of art. Bee and Schor’s project can be reconsidered today in dialogue with Kellie Jones’ search for alternative paradigms in art history. In her recent talk “Dreamwork,” the professor and author describes the aesthetic choices that the artists Elizabeth Catlett and Elizabeth Murray made during their early years of motherhood, in the everyday mess and labor of raising young children.11 Jones advocates for an art history that takes motherhood into account as a “problem-solving space” for artists. She suggests that art narratives have to change as we bring more women into the canon.12

I propose we take Jones’ thinking further and consider mothers’ “way to make [themselves] smaller, or to disappear”13 as a critical lens. Let’s look at Bee and Schor’s forum in relation to recent mother-artists’ endeavors, and particularly three compilation-based projects: Irene Lusztig’s film The Motherhood Archives (2013), Carmen Winant’s installation and book My Birth (2018), and the exhibition Art Mutters (Alone and United) (2020) curated by Annesofie Sandal. Here, too, more than it does a personal experience or a subject per se, motherhood becomes a space through which the art process can be addressed and revisited.

Irene Lusztig, “The Motherhood Archive,” (still), 91 minutes, 16 mm film, HD Video, and archival materials [courtesy of the artist]

Irene Lusztig, “The Motherhood Archive,” (still), 91 minutes, 16 mm film, HD Video, and archival materials [courtesy of the artist]

After my son was born, my time was chopped up, but I used it better …. My paintings became smaller, more detailed, more intense, and more expressive. I ceased to worry about whether people called them feminine or decorative, as these adjectives took on a positive meaning for me …. We saw the juggling and struggling as inevitable in a society that does not provide childcare, rather than the results of a personal failing. And I discovered other women artists who had experienced a rebirth in their art after having a child. This very interesting phenomenon has not been publicly explored, to my knowledge—and should be.

—Joyce Kozloff, “Forum: On Motherhood, Art, and Apple Pie”

In 2006, more than 13 years after the publication of the forum, and during the first week of her first-ever artist residency, filmmaker Lusztig learned she was pregnant. She was so overcome with nausea that she had to go home early. “The fact that my pregnancy literally coincided with the beginning and end of my artist residency career definitely made me panic about how I would be able to maintain my creative life as a new mom, and I think I’ve been reckoning and negotiating with those constraints ever since,” she confessed.14

For Lusztig the experience of matrescence was a brutal awakening, and just the beginning of a never-ending struggle to find room for herself and her creative practice. And, like many other parents, Lusztig made this constraint a space for artmaking on its own. During her pregnancy and early years of motherhood, she developed a “creative survival strategy.”15 It involved making work about motherhood from within motherhood, based upon repetitive, durational, and process-focused activities. One such project was the 2013 film The Motherhood Archives, which took her six years to finalize. This experimental documentary revisits the cultural history of birthing through a collage of more than 100 educational, industrial, and medical-training films.

When discussing the starting point of this film, Lusztig often refers to her immediate suspicion upon entering the realm of pregnancy and early motherhood in the late 2000s. Given her deep knowledge about visual cultures of propaganda—her two previous films, Reconstruction (2001) and The Samantha Smith Project (2005), meditate upon propagandist languages produced in the Cold War era—discourses regarding childbirth and pregnant women’s bodies felt fraught and ideological. In The Motherhood Archives, Lusztig created a complex filmic language to untangle naturalized ideologies about infants and mothers. Her chosen form for the film—collage of pre-existing materials—was totally “born out of the rigorous constraint of early motherhood, when it felt not possible to travel or plan ambitious shoots,” she told me in a 2020 interview.

As Bee did with the forum, Luzstig made a film to answer very personal questions. The challenges she endured as a young parent became a creative force that made her dig into marginalized questions and interrogations. With The Motherhood Archives, which exists as the prenatal documentary she critically wished for, the filmmaker asserts that motherhood is a subject worthy of attention. She fights against the “widespread perception that work about motherhood is sentimental, indulgent, narrow, narcissistic, domestic and boring, that it’s not an experience worth considering or thinking about, and that it therefore could only possibly be interesting to other new mothers.”16 This critical project marked a new path in her artistic practice, centered today on the exploration of feminist issues, and on the creation of alternative models for distributing and accessing works about women’s history and experience.17

Irene Lusztig, “The Motherhood Archive,” (still), 91 minutes, 16 mm film, HD Video, and archival materials [courtesy of the artist]

With the exception of Alice Neel and several other women artists, how often is an experienced view of pregnancy and motherhood a subject of art? Not that this has to be the exclusive imagery for women artists who are mothers, but I think it is significant that it is so neglected.

—Bailey Doogan, “Forum: On Motherhood, Art, and Apple Pie”

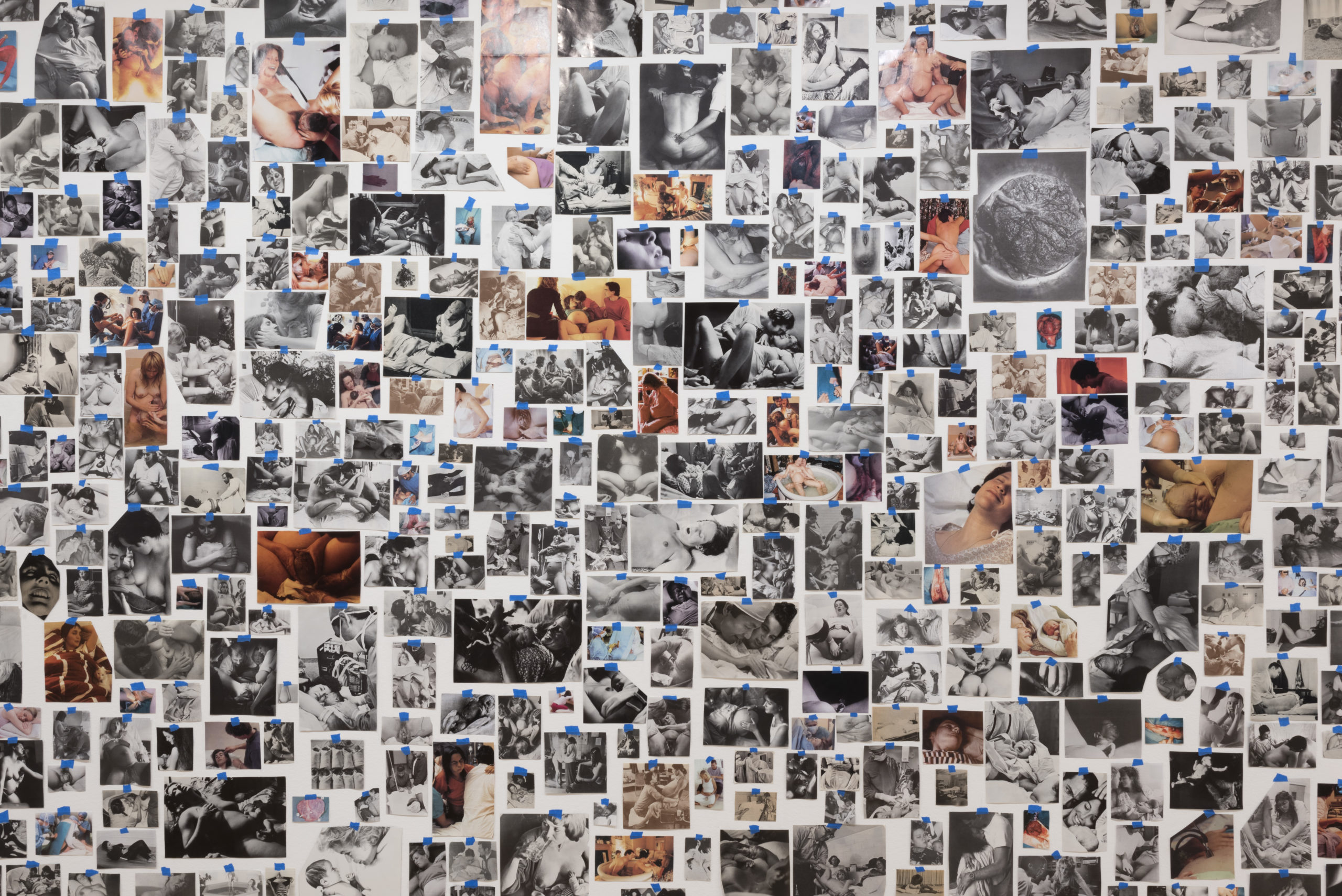

In 2016, a couple of weeks after giving birth for the first time, photographer Carmen Winant read an interview with artist Mierle Laderman Ukeles, who spoke about how, after she gave birth in 1968, no one asked her about it. Winant was profoundly touched by this testimonial, because she realized that her experience of childbirth was also surrounded by the same silence. She was eager to talk about it—she even felt it necessary—but as with Ukeles in the late 1960s, “There was no language. No one asked her questions.”18 To Winant, this void felt like an immensely cloistered experience.19

This mutism, this lack of publicness—of publicity—for what is the most universal and shared event of all, motivated Winant to experiment and search for a language, one both visual and textual, that could represent the unspoken. The photographer then produced two indexical works—a book and an in situ installation, each titled My Birth and consisting of a series of pre-existing amateur photographs of women in various stages of labor and childbirth (mostly from the 1970s, when feminists produced many health-related materials). The artifacts the artist used came from a range of books, magazines, and pamphlets that she scouted in estate sales, bookstores, personal cabinets, and garage sales.20 By amassing and collaging individual pictures together, the artist made the representation of childbirth—so intimate, unambiguous, and unapologetic an experience—look fragmentary and static. Each image becomes one short-lived and limited snapshot of a violent, Dionysian moment of a mother’s life. Winant affirms vividly and graphically that, indeed, the subject is “too big for images, too inscrutable for dialogue.”21 She suggests that this difficulty of depiction is worth our attention and time. She also asks us about the social and political meaning of this uneasiness,22 with which we look at and approach birthing: What is the role of patriarchy in this absence of language?23 By confronting childbirth pictorially, outside any sentimental cliché, fleshly parody, or sexual voyeurism, Winant entered an uncharted—and transgressive—territory. This gesture of compelling the viewer to look critically at, and contemplate, accouchement makes My Birth a radical art gesture.

Carmen Winant, My Birth, 2018, found images, tape; installation view of Being: New Photography 2018 at The Museum of Modern Art, New York, March 18, 2018–August 19, 2018. © 2018 The Museum of Modern Art [photo: Kurt Heumiller; courtesy of the artist]

The book and the installation, which share a title as two parts of one unique work, were developed concurrently until Winant gave birth to her second child. The artwork was a monumental and laborious enterprise that included the spreading and collaging of more than 20,000 images on corridor walls of the museum’s third floor. The publication was conceived as an intimate and slow-moving narrative, which follows page after page of women in labor, including Winant’s mother (some of the pictures come from Winant’s family album) and Winant herself (who narrates her own experience in the text). The artist intermingles impressions from her first child’s birth with visuals from her own birth, showing the act of giving life as a cross-generational experience that collapses chronological time. She expands this mother/child filiation by bringing strangers into the two projects: new mothers-to-be and the people who accompany them in their laborious and private journey (partners, friends, parents, medical staff). With this chorus of image and text fragments, Winant asks: “Whose birth is this?” She plays with the blurry line between I and we, between now and then. There, she presents motherhood as a moment of dispossession of oneself, wherein the split and pouring body,24 in crushing pain, is in deep relation with others. Winant investigates labor from within, from the perspectives of her body, her mother’s body, and anonymous women’s bodies.25 She claims that this shared experience binds bodies outside the regime of speech, forming a powerful but silent community. Beyond the critique of the patriarchal gaze, My Birth is therefore an artistic attempt to capture embodied knowledge within the medium of photograph. By keeping sensation within materiality,26 Winant turns the impossibility of transmitting motherhood verbally into a fertile ground for artmaking.

Carmen Winant, My Birth, 2018, found images, tape; installation view of Being: New Photography 2018 at The Museum of Modern Art, New York, March 18, 2018–August 19, 2018. © 2018 The Museum of Modern Art [photo: Kurt Heumiller; courtesy of the artist]

Carmen Winant, My Birth, 2018, found images, tape; installation view of Being: New Photography 2018 at The Museum of Modern Art, New York, March 18, 2018–August 19, 2018. © 2018 The Museum of Modern Art [photo: Kurt Heumiller; courtesy of the artist]

[The] multiplicity of roles is most often and most extremely experienced by women and is very visible … it is one more convenient rationale for a dismissive attitude towards women’s work. To my mind multiplicity is not a negative, but broadens, deepens, enriches the context for interesting and relevant work.

—Hermine Ford, “Forum: On Motherhood, Art, and Apple Pie”

In spring 2017, a few months after giving birth, Annesofie Sandal immediately went back to work and attended a fellowship program at the Bronx Museum of the Arts. For her, being a mother has been a struggle and constant juggling act, but never an obstacle in her artistic career.27 Caregiving has also been a great source of inspiration: While pregnant, she presented a solo show at Gallery Factory, in South Korea, that included a new series of objects and sculptures made from recycled and repurposed cardboard boxes. Here she drew upon the ancient Greeks’ dual conceptions of time, chronos (sequential and chronological) and kairos (conjectural and opportunistic), to consider the superposition of time in the present.28 By calling the exhibition A Pregnant Moment, she pointed out that motherhood is also a multilayered reality, wherein the body is visibly traversed by conflicting imperatives and times. Like a cardboard box, her pregnant body has become a carrier, one she also exposed in her exhibition by inserting herself into a box, with her pregnant belly popping through a large oval hole. The female body protects and connects worlds across generations and geographies.

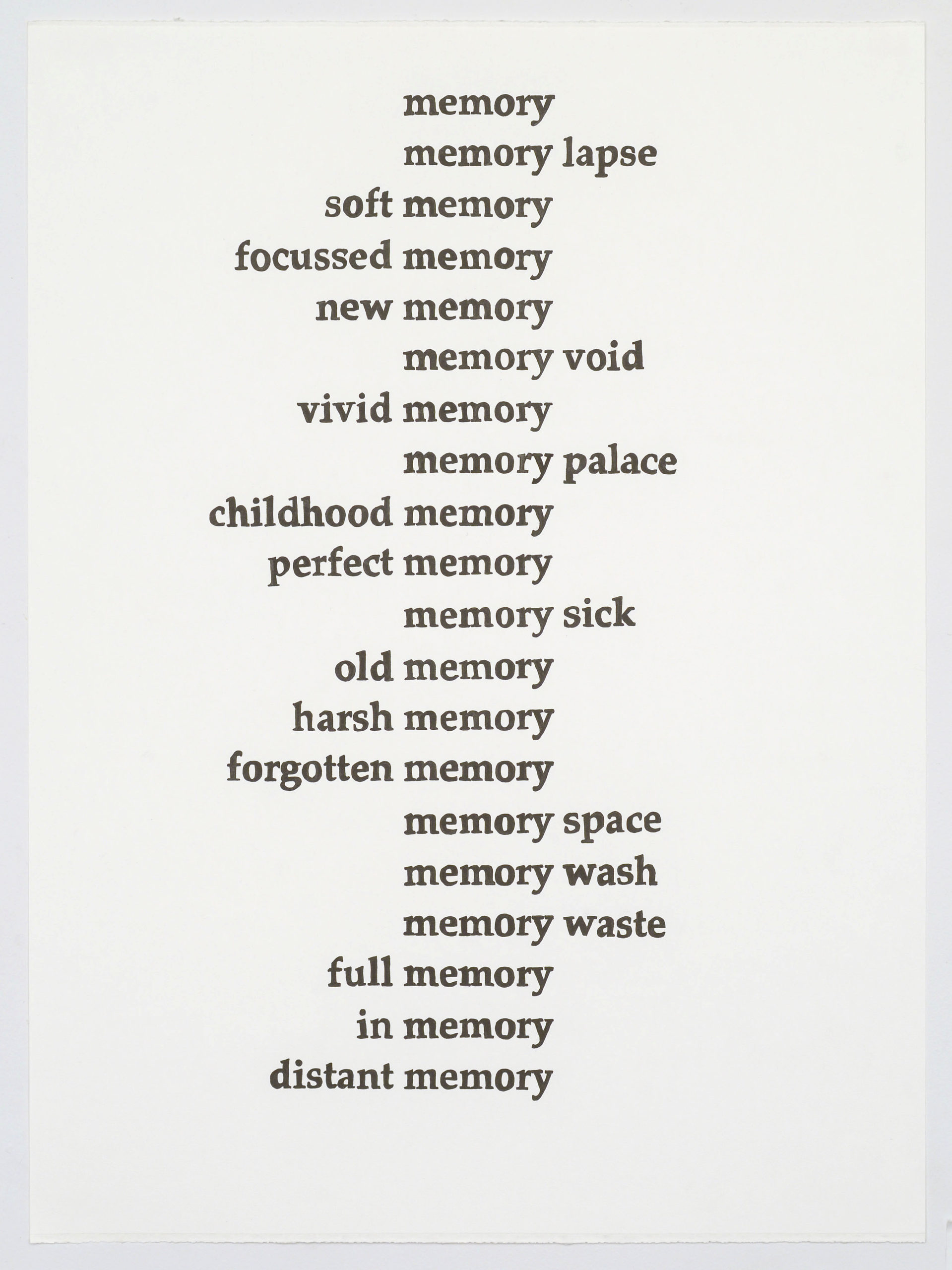

Art Mutters (Alone and United), installation view, group exhibition curated by Annesofie Sandal, at Triangle Arts Association, Brooklyn, January 21–February 28, 2020 [courtesy of Annesofie Sandal]

Sandal further continued her reflection upon the mother’s body in 2019, when she was a resident at Triangle Arts Association in Brooklyn. In that space, she curated the group exhibition Art Mutters (Alone and United), in which she included only artist-mothers. In her selection, she offered a distanced—both humorous and melancholic—view of parenthood. She evoked the physicality of the nursing body with the presence of Sophie Grant’s nippled ceramic surface , Nub (2017) and Edina Tokodi’s charcoal drawing of a turfy shelter, hut (2018). Also, with the inclusion of Freya Powell’s playful visual poem on memory, After Perec (2015–ongoing), and Sepideh Salehi’s palimpsestic paper collage of a majestic mountain, The wind sings of our nostalgia (2018), she meditated on the thickness of mothering time, which, in its collision of immediate calling and deep memory, closely ties the metaphysical to the mundane.

Annesofie Sandal, Belly Box, 2016, found cardboard and body. Installation view at Gallery FACTORY, Seoul, October 21–November 20, 2016 [courtesy of the artist]

Sophie Grant, Nub, 2016, Hand-built ceramic on cloth, 12 x 10 inches [courtesy of Annesofie Sandal]

Sandal’s exhibition was not about motherhood per se—most of the artists invited don’t consider it a theme in their practice29—but it generated a community of artists who acknowledge publicly, without taboo or reservation, that they make art while parenting. Sandal presented motherhood as a state of mind, a mode of relation and of being with others that underlies these artists’ practices without determinism. Motherhood became a possible angle for discussing, critiquing, and countering the image of the solitary artist. In this safe community, Sandal made mothers’ voices resonate, even if they are soft and low. For her, such caregiving activities are used as “an easy and superficial scapegoat to explain why [women artists] are so poorly represented in art history.”30 Sandal suggests that it is not motherhood that is in conflict with artmaking but rather the conventional narratives framing womanhood.

Sepideh Salehi, The wind sings of our nostalgia,” 2018, Inkjet print, transfer, blue carbon, acrylic medium, pencil on Japanese paper, 76.5 x 55 inches [courtesy of Annesofie Sandal]

Freya Powell, After Perec, (Memory), 2016, Ink on paper, 30 x 22 inches [photo: Cary Whittier; courtesy of Annesofie Sandal]

It’s not motherhood that triggers discrimination in the art world; it’s being a woman.

—Joan Snyder, “Forum: On Motherhood, Art, and Apple Pie”

When I visited Sandal’s exhibition and studio at Triangle Arts in early 2020, I immediately spotted a copy of Davey’s Mother Reader on her bookshelf. This book, which is also on my bookshelf, is where I read Bee and Schor’s forum for the first time. A reference book, this compilation makes visible a lineage of authors writing critically about motherhood that existed in the last 60 years but had never been assembled in one volume. Through its circulation since 2001, Davey has fed and enriched an invisible community of writers, readers, and artists interested in exploring the ambivalent place of motherhood in contemporary society, particularly in the arts.

Like the artists in Sandal’s exhibition, Davey’s art is not centered on motherhood— “except in a handful of tangential ways, when the subject crept in unannounced.”31 This experience had an impact on her practice nonetheless by making reading during childbearing—and the early years of childcare—more than a leisure: a necessity, her “lifeline.”32 In an interview, the artist admitted that editing Motherhood Readers “solidified [her] relationship to literature and it made writing —which hadn’t been central to [her] work before—more central to what [she does].’33 Even if this anthology was a side project, an activity that sustained Davey during a moment of crisis, it marked a turning point, where reading and writing became an integral part of her creative process.

Bee and Schor’s detective search for other artist-mothers, Lusztig’s obsessive compilation of educational childbearing films, Winant’s voracious acquisition of birth albums, and Sandal’s energetic gathering of artworks by mothers share this urgency—which is both a passing fad and a survival strategy—one born of isolation, frustration, and stupefaction. These women engaged themselves in an activity of collecting and editing that was both laborious and generous. They gave shape to choral forms in which their personal experience of motherhood could be unpacked aesthetically and collectively, wherein womanhood and artisthood could collide in productive ways. Each of these forums was opened from a place of confinement, from a movement of disappearance and withdrawal. And, perhaps it is there—in the limited space for expression and reflection, at the margins of public visibility and audibility— that the call for more inclusivity in the art, a demand for remodeling the paradigm of artmaking, finds its best resonance.

Mathilde Walker-Billaud is a curator and cultural producer based in New York City. She held positions as assistant editor at the Centre National de la Danse, program director at the Cultural Services of the French embassy in New York, program officer at Villa Gillet NYC festival “Walls and Bridges,” workshop programmer at UnionDocs, and creative manager at company nora chipaumire. A recent MA graduate from the Center for Curatorial Studies at Bard College, she organized and hosted lectures, screenings, and performances at various institutions, including CCS Bard, Colgate University, UnionDocs, Triangle Arts Association, Anthology Film Archives, and the Metrograph. Her more recent project is the BKH Curator Award 2020 exhibition The World Is Gone, I Must Carry You at Bonniers Konsthall, Stockholm. Her writing has appeared in BOMB Magazine, ART PAPERS, and the 2020 Isola Cinema International Film Festival. She can be heard in the podcast Benjamen Walker’s Theory of Everything.

References

| ↑1 | Susan Bee and Mira Schor, eds., M/E/A/N/I/N/G #12, November 1992, online. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Mira Schor and Susan Bee, “Mira Schor and Susan Bee Discuss the Many Meanings of Art Writing,” Hyperallergic (April 5, 2018), online. |

| ↑3, ↑30 | Interview with the artist, June 2020. |

| ↑4 | Trying to Make the Personal Political: Feminism and Consciousness-Raising, a reprint of Consciousness-Raising Guidelines (Chicago: Half Letter Press, 1975); Johanna Burton, “The New Honesty: The Life-Work and Work-Life of Lee Lozano,” in Solitaire: Lee Lozano, Sylvia Plimack Mangold, Joan Semmel (Columbus: Wexner Center for the Arts, 2008), 19. |

| ↑5 | I came across several forum or compilation projects exploring motherhood in the arts, including Dani Daeun Kim (ed.), SELFHOOD, ARTISTHOOD, MOTHERHOOD (n.p.: FACTORY, 2019); Myrel Chernick and Jennie Klein (eds.), The M Word: Real Mothers in Contemporary Art (Toronto: Demeter Press, 2011); Deirdre M. Donoghue (eds.), The m/other voices (online research project, 2013–ongoing); Natalie Loveless (cur.), New Maternalisms (curatorial project, 2010–2016); Christa Donner (eds.), Cultural ReProducers (creative platform, web resource and community-based project, 2012–ongoing); Csilla Klenyanszki, Mothers in Arts (community and residency project, 2016–2017). Worth adding to this list are the memoirs of Maggie Nelson (The Argonauts, 2015) and Sheila Heti (Motherhood, 2018), wherein the authors ask in what ways motherhood affects critical thinking and creative writing. |

| ↑6 | Moyra Davey, ed., Mother Reader: Essential Writings on Motherhood (Seven Stories Press, 2001). |

| ↑7 | Moyra Davey, “Introduction,” in Moyra Davey, ed., Mother Reader: Essential Writings on Motherhood (Seven Stories Press, 2001), xvii. |

| ↑8 | Lucia Graves, “Women’s domestic burden just got heavier with the coronavirus,” The Guardian (March 16, 2020); Claire Cain Miller, interviewed by Terry Gross, “How the Pandemic Hurts Working Moms,” Fresh Air, NPR (February 18, 2021). |

| ↑9 | Michelle Millar Fisher and Amber Winick, “A Fucking Raw Deal: Designing Motherhood the All American Way,” Vestoj, online. |

| ↑10, ↑13 | Jessica Friedmann, “Motherhood Is a Political Category,” in Human Parts, Medium.com, online. |

| ↑11, ↑12 | Kellie Jones, “Women and the Dreamwork,” conference on March 6, 2019, at CCS Bard College. Another version of this talk (on October 14, 2019, at the Wexner Center for the Arts) was documented and is now accessible online. |

| ↑14, ↑15, ↑16 | How to Do Everything: a conversation between filmmakers Kristy Guevara-Flanagan and Irene Lusztig. In Corinn Columpar and So Mayer (eds.), Mothers of Invention: Film, Media and Caregiving Labor (Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press, forthcoming). |

| ↑17 | Here I refer particularly to Lusztig’s feature film Yours in Sisterhood (2018) and her film program Mothering Every Day (curated with filmmaker Kristy Guevara-Flanagan), which I presented at UnionDocs in 2018. |

| ↑18, ↑19 | Laura Regensdorf, “Artist Carmen Winant on Why 2,000 Images of Childbirth Belong at MoMA,” in Vogue, online. |

| ↑20 | Philip Gefter, “An Artist’s Vast Collection of Images of Women (and Her Own Mother) Giving Birth,” New Yorker (March 27, 2018), online. |

| ↑21, ↑23, ↑24 | Carmen Winant, My Birth (Ithaca, NY: Image Text Ithaca/SPBH, 2018). |

| ↑22 | Laura Regensdorf, “Artist Carmen Winant on Why 2,000 Images of Childbirth Belong at MoMA”, Vogue (March 19, 2018). |

| ↑25 | Sophie Bew, “Labour and Lesbian Lands: An Interview With Feminist Artist Carmen Winant,” AnOther Magazine (November 30, 2018). |

| ↑26 | Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, Qu’est-ce que la philosophie (Paris: Edition de Minuit, 1991): 166. |

| ↑27 | Hyunju Kim (ed.), SELFHOOD, ARTISTHOOD, MOTHERHOOD (n.p.: FACTORY, 2019): 207 |

| ↑28 | Iben Elmstrom, “A Pregnant Moment,” text written in conjunction with Annesofie Sandal’s eponymous exhibition at Gallery FACTORY, Seoul, October 21–November 20, 2016, online. |

| ↑29 | Annesofie Sandal (cur.), Art Mutters (Alone and United), group exhibition at Triangle Arts Association, Brooklyn, January 21–February 28, 2020. |

| ↑31 | Email to the author, July 2020. |

| ↑32 | Moyra Davey, “Introduction,” in Moyra Davey, ed., Mother Reader: Essential Writings on Motherhood (NY: Seven Stories Press, 2001), xiii. |

| ↑33 | Leah Sandals, “Moyra Davey Discusses Her Mother Reader, 15 Years On,” Canadian Art (April 27, 2016). |