Didier William

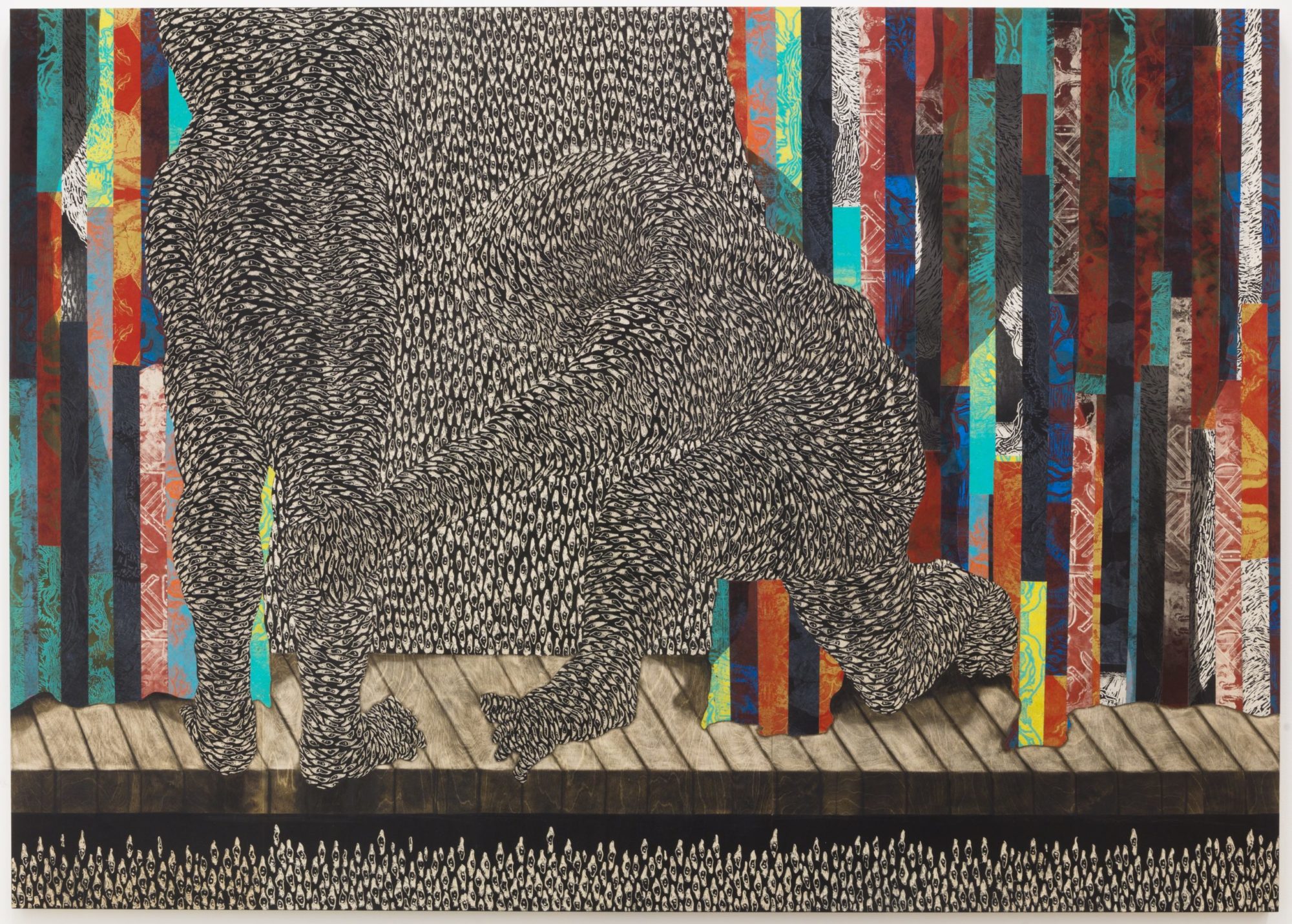

Didier William, Broken Skies: Ouve pot la pou yo, 2019, Acrylic, wood carving, and collage on panel, 65 x 102 inches [courtesy of the artist and James Fuentes Gallery, New York]

Share:

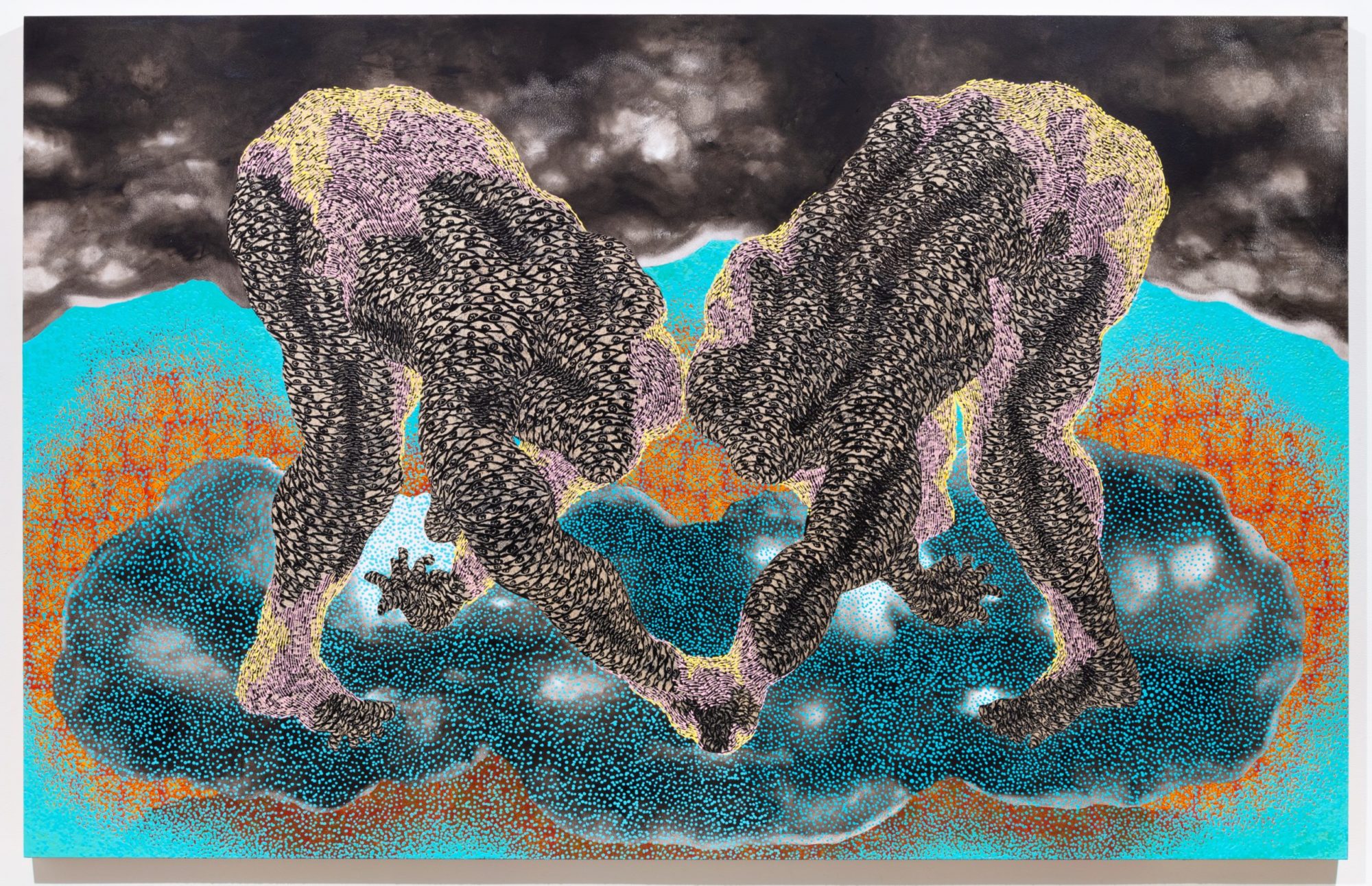

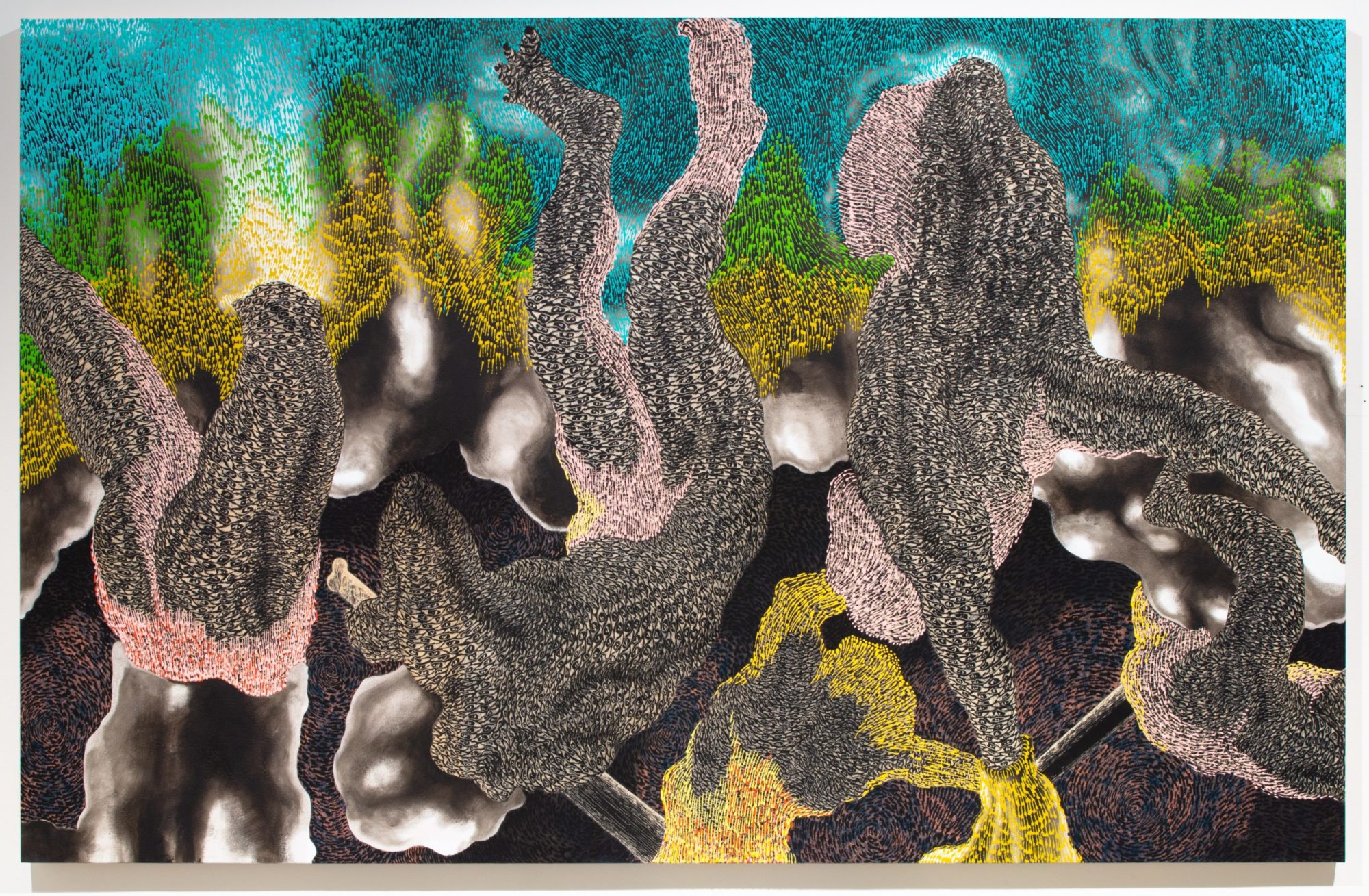

In his painting practice, Didier William seeks to diffuse and complicate the idea of the gaze. Western art history is riddled with rather nonplussed reclining nudes. The idea of the gaze can imply that there are fixed positions: those who are looking and those who are being looked at. William’s work seeks to move beyond duality, into a space of multiplicity that dismantles the gaze’s power to inscribe gender and racialize bodies. To achieve this desire he cloaks the surface of his figures in a tightly repeating pattern of eyes. The intricacy of these surfaces creates “a vibrating matrix that pulses in and out,” shifting the dynamic between the subject and viewer, figure and ground.1 This gesture slows the viewer’s ability to read the composition by requiring close, intentional looking. Not quite addressing or rejecting the fixed stare of the onlooker, the patterned eyes in William’s works become participants in viewing. They explode the closed-circuit relationship between observer and subject.

Didier William, Ou ap tonbe, men m ap kenbe ou, 2018, ink, wood carving and collage on panel, 64 × 90 × 2 inches [courtesy of the artists and James Fuentes Gallery, New York]

Regarding his approach to color, composition, and the pictorial plane, William cites the strong impact of his Haitian American upbringing in South Florida. He often uses color in nontraditional ways, applying large swaths of bright blue paint as the ground, and rich browns for the sky. His titles carry strong historic significance that underscores the theme of liberation brought forth by the patterned surfaces. Broken Skies: Vertières, for example, points to ruptures caused by colonialism, and the famous battle of 1803 in which Haiti finally won independence from France.2 Titles are often in Kreyòl, the language spoken in his parents’ home. For William, the choice to use Kreyòl not only gives his family and other Haitians agency to engage with the often too-coded space of painting, but also functions as an act of refusal against conventional Eurocentric legibility.

Didier William, Broken Skies: Te a mi, 2019, Acrylic, wood carving, and collage on panel, 65 x 102 inches [courtesy of the artist and James Fuentes Gallery, New York]

Didier William, Broken Skies: Nou Poko Fini, 2019, Acrylic, wood carving, and collage on panel, 65 x 102 inches [courtesy of the artist and James Fuentes Gallery, New York]

Allison M. Glenn is associate curator of contemporary art at Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, where she shapes the way outdoor sculpture activates and engages the museum’s 120-acre campus. She was a member of the curatorial team for State of the Art 2020, a quinquennial exhibition that opened simultaneously at the Momentary and Crystal Bridges. Previously, Glenn was manager of publications and curatorial associate for Prospect New Orleans’ international art triennial Prospect.4: The Lotus in Spite of the Swamp. Her writing has been featured in catalogues and arts publications produced by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, The Studio Museum in Harlem, Hyperallergic, and Art21 Magazine, among others.