All My …/All My— Designing Motherhood and the Labyrinth of Reproductive Health

Bernardo de Niz, Zapatista mothers breastfeeding, 2006 [courtesy of the artist]

Share:

Picture an agitated landscape—busy, fraught, and polemical. Look more and you see that it is, in fact, a maze with tortuous paths making unexpected, confusing turns. Traverse them with your gaze and you arrive back where you started, unable to make any progress. In some places, the path is blocked; elsewhere, routes converge, as in a labyrinth, toward the center. At that center is the Shrine of the Unborn Person. It’s impossible to say exactly what is enshrined there, because the Unborn Person transmogrifies. Is it a sperm and an ovum, a cell, a zygote? Is it a fetus, something glowing and mystic, like the Star Child in Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey? Is it a baby? The idol worshipped here mutates and changes, as with any elusive god, imaged differently depending upon who tends the shrine, who sweeps its altars and lights its candles.

This unstable image is how I have come to think of the post-Roe, post-Dobbs panorama. It is, in some sense, not imaginary. The political maze and the apotheosis of fetal personhood at its center now drive conversations about reproductive health and reproductive justice in the United States. No situation—within the broad context of related issues concerning individuals’ wellbeing within their communities—eludes the outsized specter of the abortion rights question. The damage done by the Supreme Court’s decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization to revoke any established constitutional right to abortion is vast and immensely complex. Michelle Millar Fisher and Amber Winick, curators and authors of the multi-platform project Designing Motherhood: Things That Make and Break Our Births, tend to call such conditions “knotty” problems.

Winick and Millar Fisher’s almost encyclopedic project makes clear that knowledge of the history, biology, and material culture of motherhood deepens awareness of the singularity of that experience. The human potential for conception (in its various biological and technological modes), pregnancy (unbound by sexuality and gender identity), experiences of childbearing and child rearing: Each situation is as distinct as a fingerprint. Millar Fisher and Winick delve deeply into the experiences and cultural practices surrounding these things, but they refuse to make blanket statements.

Sophia Harris, Postpartum faja wrap, California. [courtesy of the artist]

From its prologue to its selected readings, Designing Motherhood: Things That Make and Break Our Births (MIT Press, 2021) packs 107 chapters into 330 pages expressing an inexhaustible curiosity about/delight in reproduction, pregnancy, birth, and the postpartum. The meticulously thorough text includes wide-ranging cultural, historical, international, and indigenous perspectives and practices. Each chapter suggests additional knowledge to be gained beyond the text. Winick and Millar Fisher’s writings are sometimes authored solo, sometimes collaboratively. It’s hard to tell whose voice is whose at times—which is, I think, by design. This tangle mimics the myriad voices and collective systems within human communities around reproduction—not merely the shared human experience of childbearing, or of being born, but the multifarious social, cultural, and medical contexts in which childbearing takes place. Individual voices speak clearly and then recede into broader contrapuntal rhythms. Patterns, shared experiences, and commonalities emerge, but there is no absolute all—only the embodied, lived experience of each person intertwining with the whole.

The accompanying exhibition of the same name, which appeared first at the Mütter Museum and the Center for Architecture and Design in Philadelphia, includes medical and practical objects that surround reproduction—such things as menstrual cups, speculums, IUDs, forceps, breast pumps, the perineal repair simulator, a pair of stork-shaped clamps used to stop the bleeding from cut umbilical cords.

These designed objects required the expertise of a curator and a design historian—Millar Fisher and Winick, respectively—to link the objects’ uses to complex conventions of culture, politics, medical history, class, race, and gender. The knowledge of art experts was required to recognize these utilitarian objects as designed, and then to read them—not merely for their functional or aesthetic qualities but as containers and purveyors of the myths, attitudes, histories, and cultures through which they came to be and evolved.

Winick and Millar Fisher discuss the 400-year history of obstetrical forceps, the increasing medicalization of childbirth in the 20th century, and the natural childbirth techniques of Dr. Grantly Dick-Read within Designing Motherhood, all of which brought me a deeper appreciation of my own “accidental” home birth. A chapter on the invention of forceps includes a harrowing, baroque tale of two brothers, the French Huguenot barber-surgeons Peter Chamberlen the elder and Peter Chamberlen the younger. To hide their invention from competitors, the brothers used such elaborate measures as keeping it in a cloth-covered, gilded box and using bells during delivery to mask its metallic sounds. Their heirs, who remained in the family business of obstetrics, unsuccessfully attempted to sell the invention for profit.

Sveva Costa Sanseverino, Grandmother pushing grandchild through a parking lot in Clapham Common, South London, 1996. [courtesy of artist]

My mother’s first child—my older brother—was born after a long wait in a crowded, noisy maternity ward. She was grateful that her bed had been by a window so that she could look out at the busy street and the trees instead of merely listening to the pain of other solitary women on the ward. When it was “time,” she was “knocked out” and her baby “extracted.” Several years later, pregnant with me, she discovered the British obstetrician Grantly Dick-Read’s 1933 book, Natural Childbirth, and she found an OB willing to let her attempt these practices. When she went into labor, she remained happily at home, breathing through contractions, but departing too late for the hospital. I was delivered on the stairwell landing of the Victorian duplex in which my parents lived, into the hands of my paternal great-grandmother. My mother was triumphant. She had taken a risk (purposely or not—that has never been clear), but she had outwitted the system, taken ownership of her own body, and granted herself and me the opportunity to share my emergence into the world.

Such personal and distinctive stories abound in Designing Motherhood, which includes a plethora of works by visual artists and filmmakers, references to such cultural icons as Beyoncé and Lucille Ball, and interviews with a diverse range of activists and experts. I understand the point of my own birth story more clearly after spending time with the texts and objects in Designing Motherhood. Each woman is, in fact, alone. Each navigates the systems of her body and the systems amid which she lives. The potential for pregnancy, the related choices about that pregnancy, and the effects of those choices and circumstances can be closer-held secrets than the Chamberlen brothers’ forceps.

Aspects of the medicalization of childbirth in the 20th century include not only the deployment of a range of instruments, such as forceps, but a practice of anesthetizing laboring women while their husbands paced in waiting rooms colloquially called “stork clubs.” These women would awaken to be introduced to babies in whose births they had not consciously participated. The systems that might compassionately and wisely support the wellbeing of a person capable of pregnancy have been contested sites throughout time and history. Autonomy, agency, and privacy—if they were available, which, currently, they are only inconsistently and according to privilege—don’t mitigate this loneliness.

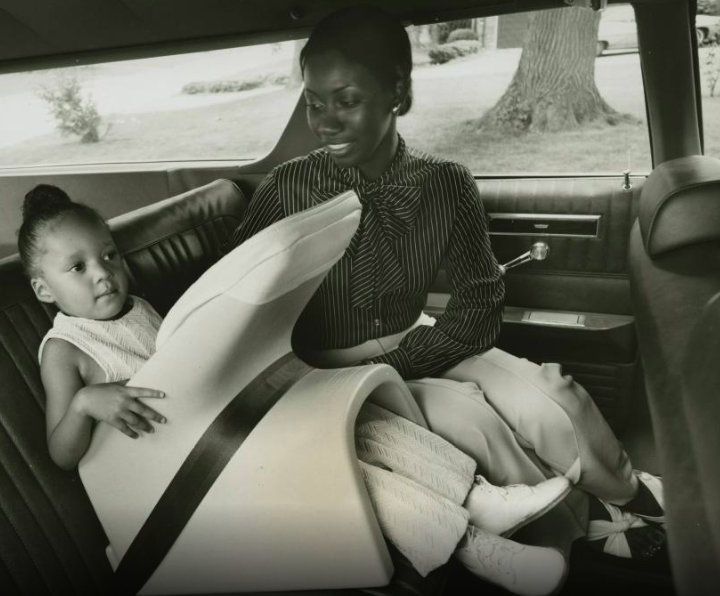

The breathtaking range of topics in Designing Motherhood—choices of whether to conceive children or take a pregnancy to term, infant mortality, sterilization abuse, thalidomide, cesarean birth curtains, masculine birth, baby formula, the faja (a wrap for binding a postpartum abdomen), gender reveals, the Del Em Device, car seats, carers and carrying, the tie-waist skirt, the breast pump, and so on—reveals the immense, intricate knowledge necessary to understand reproductive health, and to advocate for conditions that promote wellbeing.

In an interview in Designing Motherhood with Millar Fisher and Winick, Khiara Bridges refers to “a disparity between how pregnancy is imagined and how pregnancy is lived.” This disparity is rooted in lack of knowledge and the power dynamics of social ideologies. Exploring the project Designing Motherhood, I am constantly reminded how much there is to learn of the contexts surrounding reproductive issues, as well as how much their elements diverge over time and place. This humbling reminder is one of the project’s gifts.

It’s axiomatic that we can’t see what we don’t know, but the extent of public misinformation about these issues can be surprising. For example, recent New York Times “America in Focus” pieces compared the views held by 10 pro-choice voters and 12 anti-abortion voters in the aftermath of the Dobbs decision. Although the two groups’ ideas overlapped in fascinating ways, most interesting to me was a shared lack of accurate medical information, including the belief that abortion is more dangerous than giving birth (labor and delivery are in fact 14 times more likely to result in death), a misunderstanding of when an actual fetal heartbeat develops, lack of knowledge about abortion pills, and a belief that a large percentage of abortions occurs after the first trimester (less than 10 percent of abortions take place after the first 12 weeks of pregnancy). The New York Times wrote that it wanted “to understand the degree to which widespread misinformation about later abortions and abortion safety … had affected [the pro-choice] group,” but this ignorance was shared by both groups.

Similarly, the Turnaway Study, conducted by a team of researchers led by Diana Greene Foster at the UC San Francisco ANSIRH (Advancing New Standards in Reproductive Health), has provided evidence to amend the widespread belief that abortions adversely affect women’s mental health. On the contrary, the Turnaway Study shows that access to an abortion often preserves the mental, physical, and economic health of mothers and children, and that being denied an abortion tends to exacerbate their risk of trauma, poverty, physical abuse, and mental health issues. Yet the misperception persists that abortions are traumatic and disruptive to families.

Philippe McLean, Woman wearing sari, 2006, Bengaluru (then called Bangalore), India [courtesy of the artist]

The absence of knowledge and the continual flow of misinformation about reproductive health and justice—and what must be characterized as a general “fuzziness” about the facts within the general public—reveal the critical necessity to disseminate accurate and necessarily wide-ranging information. It’s no accident that Designing Motherhood’s exhibition included the 1976 “revised and expanded” edition of Our Bodies, Ourselves. Simply put, people need accurate information.

But misinformation is not accidental, and here is the deeper problem we now face. Much has already been said, and will need to be said, about the cruel effects of the Dobbs decision and the difficulty in restoring any constitutional right to abortion. Fundamental to this process is recognition that the anti-abortion crusade—the cult of unborn personhood and the impossible labyrinth it has created—is but one aspect arising from the Christian nationalist movement’s deliberate indoctrinations. This crusade is neither new nor ingenuous, but is ideological, strategic, and entrenched.

In The Fragility of Things: Self-Organizing Processes, Neoliberal Fantasies, and Democratic Activism (2013), political theorist William E. Connolly examined the “creative emergence of the neoliberal-evangelical resonance machine, starting in the 1970s ….” Connolly notes that this efficient political mechanism envelops wide cultural ground and “now consists of parties who hold overlapping political-economic theories bolstered and intensified by some affinities of existential spirituality. They share the dogma that together they should have full hegemony.” The journalist Katherine Stewart, author of The Power Worshippers: Inside the Dangerous Rise of Religious Nationalism (2020), whose comprehensive investigation of the Christian nationalist movement includes observation of its internal workings, recently wrote in The New York Times that “breaking American democracy isn’t an unintended side effect of Christian nationalism. It is the point of the project.” She added that it is “a mistake to imagine that Christian nationalism is a social movement arising from the grass roots and aiming to satisfy the real needs of its base. It isn’t. This is a leader-driven movement.” Such is the nature of authoritarianism.

Its totalitarian schemata require semantic controls—propaganda—that, in its anti-abortion and “pro-life” agenda, appropriates the language of morality, thus creating the mythos that it is the ethical conscience of love and of community and family tenderness. Worship of “the unborn person” and the verbal coding of “right to life” are by design. Victor Papanek—quoted in Designing Motherhood—defines design as “the conscious … effort to impose meaningful order.” Sophisticated ideological arguments underpin the neoliberal-evangelical position. For example, philosopher Francis J. Beckwith’s avowedly nontheological—but absolutist—moral, philosophical, and legal reasonings, or the calculated effort to enact feticide laws that are now handy for criminalizing abortion. Individuals can thereby be brought into this movement on the basis of structured “meaning” and subsequently driven by emotion through the repetition of catchphrases and vivid descriptions regarding the fate of the venerated unborn.

Such ideological propaganda feeds both misinformation and public action, often to an absurd degree. Maternal-fetal specialist David N. Hackney provides a salient example. He relates—in a New York Times guest essay, “I’m a High-Risk Obstetrician, and I’m Terrified for My Patients”—that, in 2019, the Ohio section of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, which he chairs, “successfully fought HB 413 [in the Ohio state legislature], which would have made ‘abortion murder’ a crime and could have required doctors to ‘reimplant an ectopic pregnancy into the woman’s uterus,’ which is impossible.” In the switchback pathways of absolutism, anything is possible, everything is justified, and all manner of harms can be accepted on the basis of devotion.

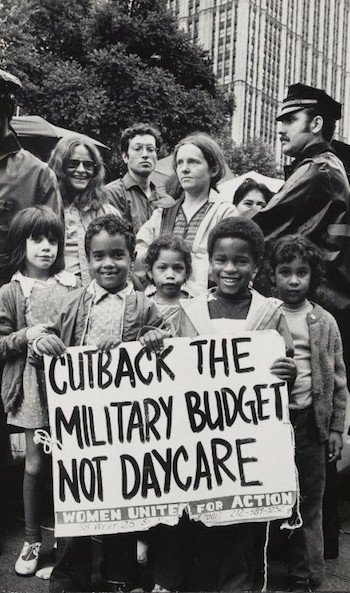

Bettye Lane, Children played a highly visible role in demonstrations for affordable child care in New York City, 1974 [courtesy of Schlesinger Library]

You cannot have a conversation with propaganda, as Khiara Bridges has eloquently demonstrated. UC Berkeley School of Law professor and anthropologist Bridges focuses her expertise on racial and class disparities in reproductive rights. Her interview in Designing Motherhood articulates the need for precise words in the discussion of reproductive rights and the extent to which abortion rights are but one piece a larger issue. She says, in part, “Not to naysay that fight at all—abortion rights are incredibly important—but while Black women have confronted the same restrictions on the ability to terminate a pregnancy that’s not wanted, they have also confronted restrictions on the ability to become pregnant and to carry to term a pregnancy that is wanted …. Black women have fought for the right to become mothers, to become pregnant, to give birth, the right to parent the children they give birth to with dignity and humanity. We have Black women to thank for conversations around the right to have a birth experience that accords with your values, your needs, and your health.”

Dr. Gayle Nelson, Mama breastfeeding, 2020 [courtesy of Gabriella Nelson]

Ford Motor Company’s “Tot-Guard”, 1973 [courtesy of the Collections of The Henry Ford Museum]

In July of this year, Bridges appeared during the Senate Committee on the Judiciary hearing “A Post-Roe America: The Legal Consequences of the Dobbs Decision.” This hearing became a case study in the impossibility of contemporary discourse, in addition to demonstrating that current public systems for debate are not designed for nuanced discussion. Bridges was asked two particularly loaded questions, one by John Cornyn (R-TX), who asked whether she believed that a baby who is not yet born has value, and one by Josh Hawley (R-MO), who asked whether she meant “women” when she “referred to ‘people with a capacity for pregnancy.’” To Cornyn’s question, Bridges steadfastly maintained that “a person with the capacity for pregnancy has value,” and in an exchange with Hawley that went viral, she pointed out the underlying transphobia in his question. Bridges has been both lauded and criticized by pro-choice activists for her responses. Some critics cited, in particular, the need to affirm reproductive rights as “a women’s issue.” Others argued that she failed to clarify, for example, that a pregnant 10-year-old could hardly be considered a woman.

But Bridges could not have answered these questions differently, because they were trick questions—trap doors at the end of dead ends—designed to force her back into the cant of Christian nationalist rhetoric, that the unborn have transcendent, unlimited rights, and that only cisgender women are viable mothers (and by extension, that only cisgender people are deserving of human rights). Adept at this linguistic struggle, Bridges refused to walk into the traps. Unfortunately, that refusal, within the highly coded structure of the hearing, prevented her from articulating her nuanced, extensive support for pregnancy and women. And this deflection is precisely the point: that the discussion of reproductive health and justice has been derailed by a clever strategy. If it is to progress, the conversation must be repositioned outside the polemical landscape.

In the same hearing, repeated smarmy statements by anti-abortion senators regarding the higher percentage of abortions among Black women—such as Ted Cruz’s (R -TX) professed grief for the “millions of African American children who have never had a chance to live and to contribute to our country”—was a deliberate denial of the racial and socioeconomic disparities faced by women of color and a more than implicitly racist condemnation of Black women who have chosen abortion. The Designing Motherhood exhibition included a 1953 film by George C. Stoney, All My Babies: A Midwife’s Own Story, produced for the Georgia Department of Public Health. An instructional film for Black midwives, All My Babies is an aching cliffhanger, shot in exquisite black-and-white chiaroscuro. Its original score—sung by the Musical ArtChorus of Washington, DC—lauds a baby’s arrival with transcendent gospel fervor. A neatly edifying film, it tucks relevant details about the safe and sanitary home delivery of babies into the story of Miss Mary—actual midwife Mary Francis Hill Coley—as she follows two pregnancies and delivers two babies. It is also propaganda.

Audra Melton, Retired Atlanta-based social worker Sharon Wood holding a pro-choice pin and patch she last wore in 1973,2019 [courtesy of the artist]

The poverty and segregation of the Southern Black community are palpable in the film’s depiction. A White doctor and nurse supervise the Black midwives, gesturing toward the medicalization of pregnancy and childbirth, as well as the medical patriarchy that actively sought to wrest care from the midwives. The film never suggests that Black women should have access to full medical care. Its intrusion into the intimacy of a live birth—a 15-minute, real-time sequence filmed by a White crew—is never questioned. Neither are decisions to show the preparation for delivery, the cleaning of mother and newborn infant, or the expulsion of the placenta (which is wrapped in newspaper and dropped right into the flames of a wood stove).

Marybell, one of the pregnant women attended by Miss Mary, is desperately poor. She is shown as isolated, without community interactions, and the voiceover opines that it is impossible to know what she’s “thinking.” Yet, once her premature baby arrives, an unaccountable change occurs. Neighbors suddenly appear, offering help and congratulations, and, at Miss Mary’s instruction, her husband races to the clinic for a portable hot-water incubator. The baby survives and thrives. Marybell is said to be eating better, and the impoverished parents inexplicably can afford handsome baby clothes and a photographic portrait of the proud father and son.

The narrative imagines an enigmatic postpartum wellbeing to suggest an “up by their bootie straps” success story, an extension of the long-perpetuated American myth of self-reliance. The fantasy that people—even babies—are most moral when they are self-reliant is deeply embedded in fallacies surrounding reproductive health and justice. The anti-abortion storylines profess concern for every life, but fail to account for the social and economic needs required for effective care.

In Designing Motherhood, All My Babies was screened on a small monitor at the center of Aimee Gilmore’s Milkscapes (2016–present), inkjet images of breastmilk stains printed on a vast mylar sheet. The pooling brown stains could be breastmilk, menstrual fluid, or postpartum discharge, a map of the reproductive body’s cyclic effluvia. Similarly, Ani Liu’s Ecologies of Care (May 27–August 6, Artists Alliance, Inc.) documents the constant labor of the postpartum mother’s body. In the work Labor of Love, Liu, a research artist, data scientist, designer, architect, and mother, tracks the invisible labor required to care for her baby: the countless hours spent breast feeding. Liu translates the constant bodily production of breast milk—the baby attached to your breast, or the breast attached to a pump—into looping coils of fluid that pulse throughout the gallery. The artist makes tangible the continual, ignored, and unrecompensed demands of care.

A vitrine of IUDs in Designing Motherhood, lined up like so many Alexander Calder stabiles for doll houses, have a surprising aesthetic beauty. They are not merely a display of a modern, highly effective form of birth control but also highly designed objects that the book and exhibition map to a tortured history: from the development and marketing of the IUD, to their endangering of women through risk of sepsis thanks to the dangling thread of A. H. Robins pharmaceuticals‘ version and that corporation’s failure to publicly disclose the loss of fertility and life that resulted. The row of delicate objects leads ultimately to a public intellectual and activist, Loretta J. Ross. Ross, also interviewed in Designing Motherhood, developed an acute inflammatory pelvic disease from the wick in the Dalkon Shield. Taken to the hospital in a coma, Ross was subjected, without her permission, to a total hysterectomy performed by the same doctor who had been misdiagnosing her symptoms for six months, thus ending her fertility at age 23 and effectively amounting to a forced sterilization. As a Black woman whose agency was negated at the hands of the medical system, Ross became a leader and co-creator of the reproductive justice movement. She served as program director for the National Black Women’s Health Project and founded SisterSong Women of Color Reproductive Justice Collaborative, a Georgia-based national organization that advocates for “institutional policies and systems that impact the reproductive lives of marginalized communities.”

Dalkon Shield (far left) intrauterine device used in the early 1970s and 1980s and produced by the A.H. Robins Company in the US. It caused an array of severe injuries, including pelvic infection, infertility, unintended pregnancy, and death. Eventually the US Food and Drug Administration banned the device. [Image courtesy the Mütter Museum]

The topography of care is difficult, intricate, and heterogeneous. It requires a recognition that the titular “all my” evoked in stories of reproductive health is singular, and variable, even within individual experiences. And unlike the polemical maze surrounding the enshrined unborn person, the phrase is not mythological, absolute, or authoritarian. Writing in the feminist journal Hypatia in 1994, philosopher Elizabeth Porter argued that the conversation about abortion ethics—and, by extension, the ethics of reproductive justice—requires a praxis that is a “morally acute dilemma that involves reflecting on the dialectical interplay between rights and responsibilities, in view of personal life narratives, and making [decisions] based on one’s social, cultural, and personal contexts.” Navigating this landscape requires a refusal of binary dogmas—a refusal to argue with propaganda—and a confident reclamation of moral discourse. This labor of love—and it is labor—will require strenuous and continuous legal, educational, and political action, in addition to a commitment to individual wellbeing.

I finished writing this essay with my newborn grandson in my arms. His mother, an equestrian athlete and clinical social worker—a woman of exceptional physical and emotional strength—has long expressed skepticism about the medicalization of birth in the US. Because the baby was head down but face up, her labor required her to push for five hours and, ultimately, for the safety of baby and mother, a vacuum-assisted delivery (an alternative to forceps). Her story is a reminder that—as Designing Motherhood and a multitude of other artworks, exhibitions, and activist voices demonstrate—there is no single, unified story. There is only individual embodied experience, which cannot be shared, but which—like a fingerprint—can be recognized. Beyond empathy for this private, lived experience is the capacity to speak, to share one’s experience, to gain knowledge, to accurately tell histories, to correct mistakes of the past. Such is the work that Designing Motherhood does. Much in it is corrective, much of it shines a light on abuses, the power of politics, and the tragedies that have occurred in that history to disseminate the kind of embodied knowledge which makes healthy power possible. It is the kind of labor we are all called upon to do.

These observations are dedicated to my grandchildren, Mimi and Milo, for whom I wish lives of knowledge, integrity, and agency.

Dinah Ryan is Cornelius Ayer and Muriel Prindle Wood Professor of the Humanities at Principia College. She has been a contributing editor for ART PAPERS since 1992.