Derek Fordjour: SHELTER

Derek Fordjour: SHELTER, installation view, 2020 [courtesy of Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis; photo: Dusty Kessler]

Share:

A curtain of olive branches frames the profile of a Black man. The painting shows him in a bust view, allowing his broad shoulders and back to consume the majority of the canvas. The man’s features are demurely obscured by this staged pose and by a shadow that falls across the edges of his profiled face. What can be seen of those features exudes contentment. His eyes closed, the man is rendered indifferent to the gaze of the viewer. The mixed media composition gives the canvas a weathered appearance, amplified by its surface of muted grays, blues, and purples that appear to crackle and chip to reveal a warm and vibrant pink underlying the man’s image. Materials, such as corrugated cardboard, clipped photographs, and book pages are layered into a fragmented surface that evokes the imagery of abandoned and disintegrating billboards.

The Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis’ exhibition Derek Fordjour: SHELTER marked the artist’s first major solo museum exhibition and stood as a significant exploration into the problematics of Black visibility in American visual culture. The untitled painting described above is but one in a series of 100 works titled Players Portraits by interdisciplinary artist Derek Fordjour. Viewed on its own, the painting displays meticulous detail and materiality. When viewed within the series, however, the individual characteristics of the portrait are diminished by the greater impact of the group. Fordjour created these portraits to have the same dimensions and similar composition to mimic the aesthetic of athletic trading cards. Each portrait depicts a Black man with eyes closed, dressed in one of several similar athletic uniforms, and shown in profile. Playing upon a global history of visual culture that seeks to render the bodies of Black men into interchangeable sources of commodifiable labor, Fordjour illustrates the way hypervisibility of Black people can render them invisible.

Derek Fordjour: SHELTER, installation view, 2020 [courtesy of Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis; photo: Dusty Kessler]

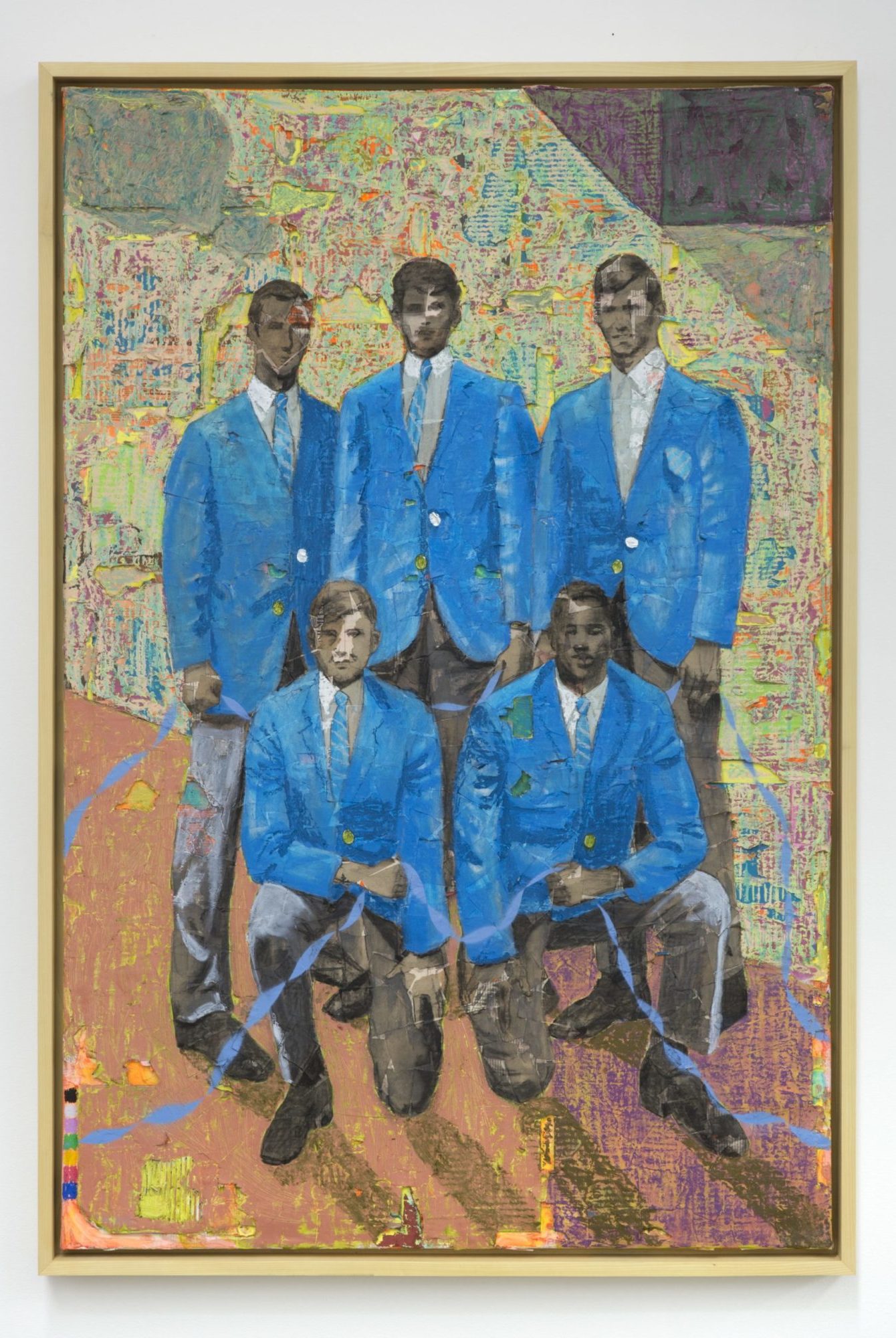

Derek Fordjour, Tandem Blue, 2018, acrylic, charcoal, oil pastel and foil on newspaper mounted on canvas. 40 x 60 inches [courtesy Night Gallery, Los Angeles]

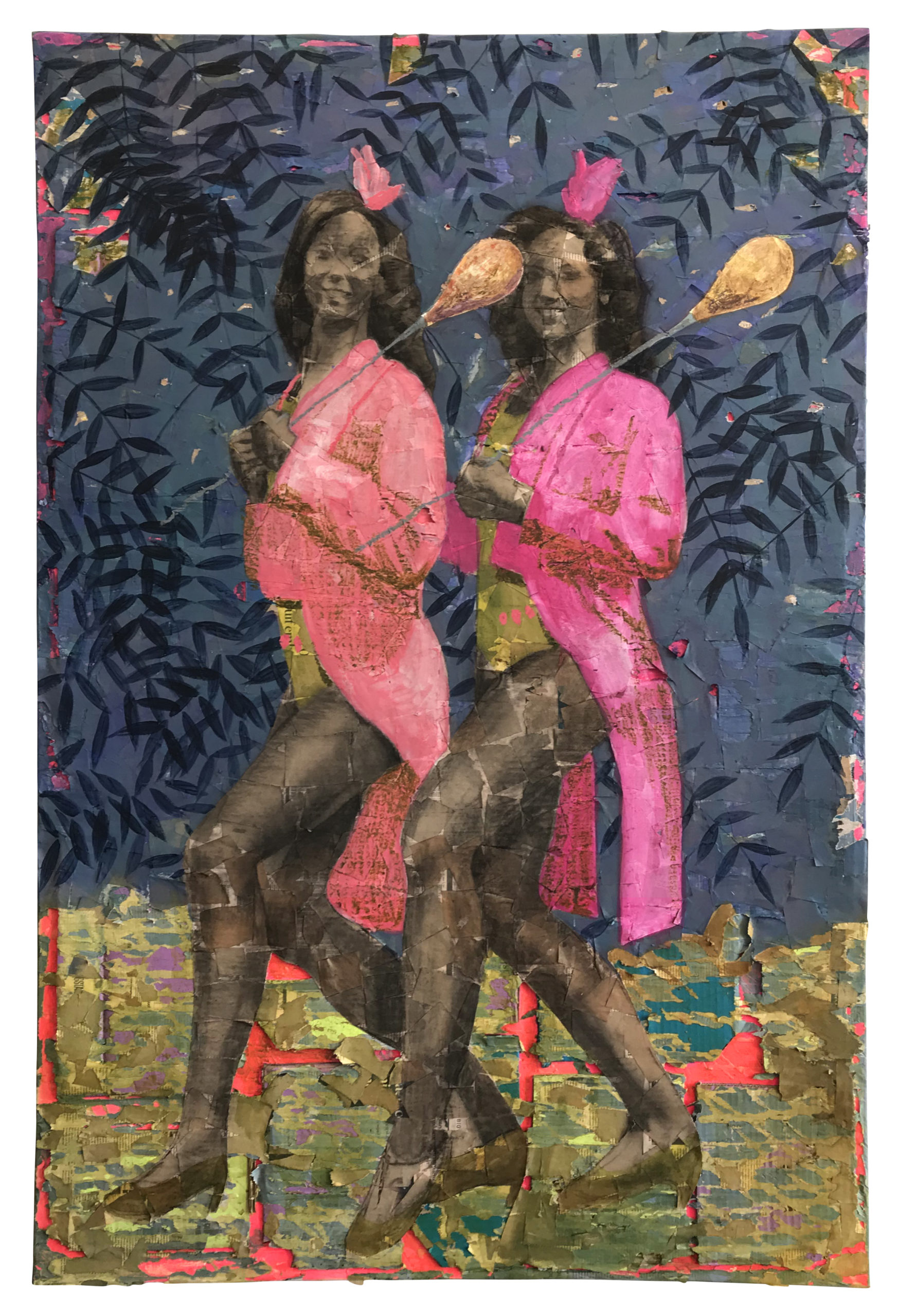

Derek Fordjour, Two More Years, 2018, acrylic, charcoal, oil pastel, and foil on newspaper mounted on canvas, 40 x 60 inches [courtesy Night Gallery, Los Angeles]

Going beyond examples of positive representation and inclusion, the concept of visibility calls for interrogating how and why certain depictions of Black people are deemed accessible. Western viewers are conditioned to expect certain depictions of the Black body and Black experiences, such as the hypervisibility of violence against those bodies. That hypervisibility renders other realities of Black experience—such as the beauty of Black joy—invisible. Fordjour seems most concerned with the hypervisibility of Black exceptionalism. His subjects often appear in scenes of pageantry or performance that many viewers might interpret as positive representations. Fordjour complicates that surface reading to reveal the complexities of Black exceptionalism and how the proliferation of certain “positive” images can also erase and perpetuate violence. Fordjour’s series replicates the visual consumption of the images of Black men en masse, which leaves the paintings vulnerable to the viewers’ biases. It is left to the biased viewer to determine whether the figures in these portraits are athletes, whether they are children, or if the paintings depict various images of the same man.

Derek Fordjour, Aquatic Composition, 2019, acrylic, charcoal, oil pastel on newspaper mounted on canvas, 60 x 100 inches [courtesy Josh Lilley Gallery, London]

The 24 portraits from the Players Portrait series presented in SHELTER offered the perfect entry point for an immersive gallery experience that transformed the traditional exhibition space. Above the entrance to the installation extended a large sheet of corrugated metal, like an awning or an open maw. It simultaneously invited viewers and forewarned them of the stark environmental shift ahead. Beyond this introduction, the walls and ceilings of SHELTER were constructed with fortified but uneven rusted sheets of corrugated metal and draping blue tarps, which enclosed an 800-square-foot maze-like space.

Construction-site lighting hung between the ceiling’s gaps, lighting the installed artworks and casting deep shadows on the nooks and corners of the space. The installation’s floor was completely covered with packed dirt and debris. The dirt was loose and uneven in places, making viewers’ footing uneven, awkward, and unstable. Used food wrappers and cotton bolls could be found partially buried in the dirt, further blurring the space’s sense of location and time. Completely abandoning the white cube, SHELTER mimicked—in form and material—the corrugated metal dwellings often associated with extreme poverty and migration. This metal structure allowed viewers to depart from the gallery space and enter one that, for some, evoked distant feelings of the unfamiliar and the unsafe, whereas for others it evoked the immediate familiarity of home.

Derek Fordjour: SHELTER, installation view, 2020 [courtesy of Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis; photo: Dusty Kessler]

Sounds of a simulated storm vibrated through the structure, mimicking the threat of a torrential downpour just beyond the thin metal walls. The structure’s seeming instability conjured an energy charged with potential to trigger the instinct of fight or flight. SHELTER’s exhibition design opened an imaginative space for viewers to confront the concepts of safety and security—especially for vulnerable populations—in the face of literal and metaphorical storms, and it visualized the unstable conditions from which Black exceptionalism often emerges.

Within SHELTER, Fordjour’s paintings show vibrant and celebratory imagery of Black people in costume, posed and smiling, or caught in the action of athletic performance. Five Down Wide (2019) is a large-scale painting that depicts a line of majorettes performing splits. The faces of the individual women are slightly abstracted by Fordjour’s multimedia compositional style, making the details of their facial expressions difficult to see. The focus of the painting becomes the uniformity of their postures, the bright color of their sequined costumes, and the high extension of their white-gloved hands. Fordjour’s depictions present aspects of Blackness that to non-Black people are most visible, most pleasurable, and most commodifiable.

Derek Fordjour, “Five Down Wide,” 2019, acrylic, charcoal, oil pastel and foil on newspaper mounted on canvas, framed, 40 x 100 inches [courtesy Night Gallery, Los Angeles]

Jovial expressions of culture, exertion of physical labor, and the spectacle of Black achievement despite adversity form the public façade that often renders other realities of Black life invisible. The uniformity of the smiles on the women’s faces is obscured so that they must be then inferred or assumed by the viewer. Their talent, an assumed result of practice and athleticism, is laid bare for the viewer’s external validation. The violence lies not in physical wounds to the body but in psychological wounds inflicted when one must perform to survive. This façade serves as a cage for the most visible, reducing the vibrant interiority of people to their singular achievements, how well they entertain, and the spectacle of their bodies. Reflexively, the exceptional achievements of one can be weaponized against the vulnerable many for their inability to achieve success.

Fordjour’s installation invited viewers inside a multisensory interior space that gave them a new way of approaching his work. The juxtaposition of the tarpaulin, dirt, and rusted metal sheets in the installation teased out the rich materiality of the sculpture and paintings in ways the white cube could not. Found materials sourced from local streets push back against the hierarchy of art materials to reveal the beauty of newspaper, foil, and cardboard. The corrugated walls of SHELTER and the sheen of blue tarp reflected in the canvases’ surfaces. However beautiful and awe-inspiring these depictions of Black people may be, they abide by the adage of making something out of nothing—which, again, reflects the conditions from which Black exceptionalism often springs. A line of Black majorettes doing splits or a Black man posing in a formal school uniform is more clearly seen as posturing, uncomfortable, and performative, thereby laying bare the acute awareness Black people—including Fordjour—have of their own consumption by the gazes of others.

TK Smith is a writer, critic, and curator based in Philadelphia. For ART PAPERS Spring 2020, he contributed an impassioned and deeply personal take on the problematics and potentials for representation of the Black people in Toward a Monumental Black Body. He is currently a Tina Dunkley Curatorial Fellow in American Art at the Clark Atlanta University Art Museum. In Fall 2020, he will begin a PhD program in the American Civilization Program at the University of Delaware.