Cross Pollination: Heade, Cole, Church, and Our Contemporary Moment

Vik Muniz, Orchid and Three Brazilian Hummingbirds, 2013, digital C print, 40 x 53 inches, ©Vik Muniz / VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY [courtesy of the Cummer Museum of Art & Gardens, Jacksonville, FL]

Share:

In his 1836 “Essay on American Scenery,” the painter Thomas Cole wrote of civilization’s detrimental impact on the natural world: “The wayside is becoming shadeless, and another generation will behold spots, now rife with beauty, desecrated by what is called improvement.” Cole’s essay is a key point of reference in Cross Pollination: Heade, Cole, Church, and Our Contemporary Moment. Organized by the Thomas Cole National Historic Site, the Olana Partnership at the Olana State Historic Site, and the Crystal Bridges Museum of Art, the nationally touring exhibition makes a manifold proposition: to explore the connections between art and science apparent in the works of Cole as well as Martin Johnson Heade and Frederic Church—his immediate heirs—alongside recent artworks that accentuate Cole, Heade, and Church’s ecological underpinnings.

Frederic Edwin Church, View on the Magdalena River, 1857, oil on canvas [courtesy of the Cummer Museum of Art & Gardens, Jacksonville, FL]

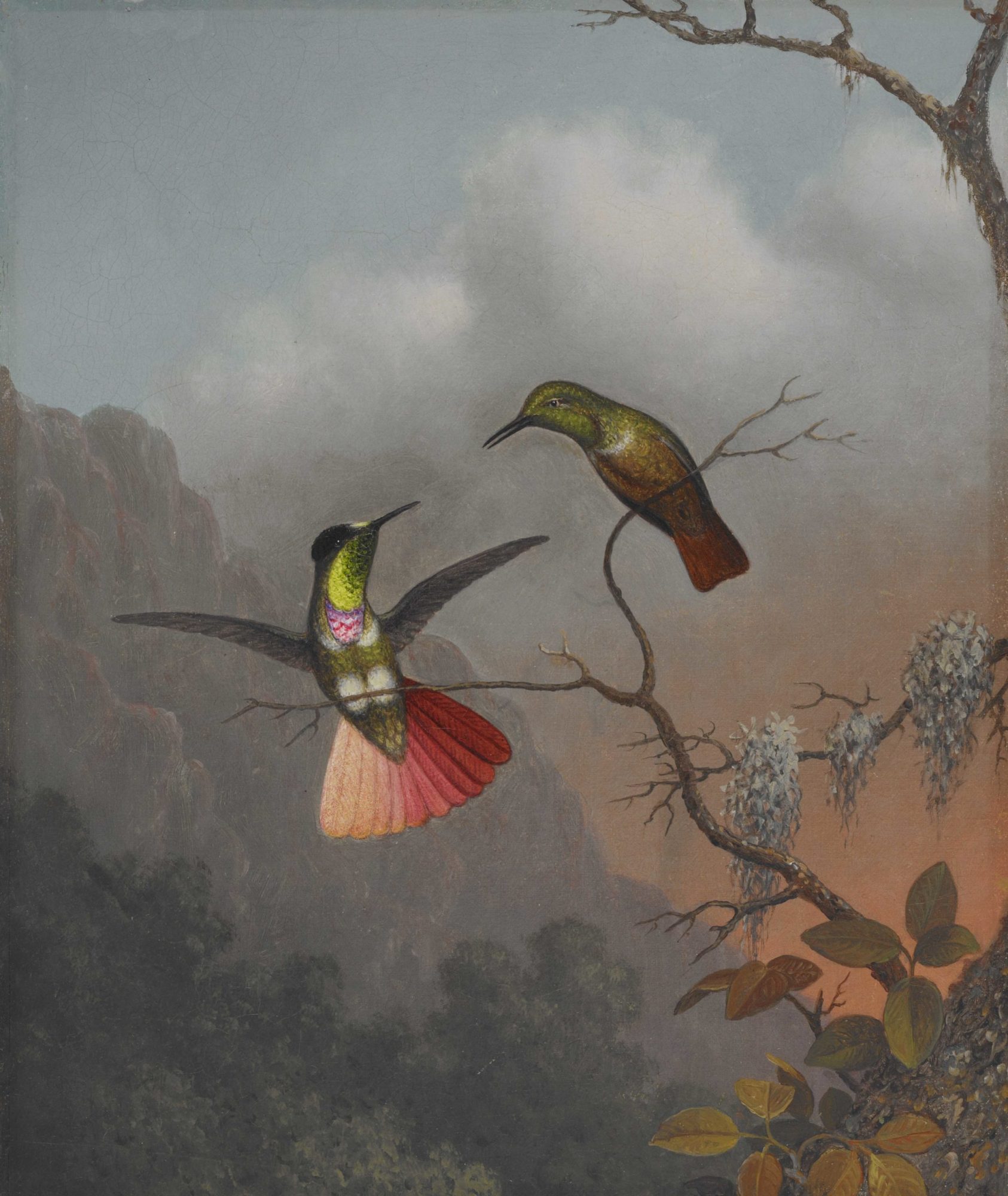

A centerpiece for the exhibition is a set of 16 paintings from Martin Johnson Heade’s series Gems of Brazil. Dating from 1863–1864, these modestly sized oils were conceived as the basis for a book of the same name, but the project was abandoned thanks to a lack of funding. Hung in two rows, Heade’s paintings detail a variety of hummingbird species (and one blue morpho butterfly) while also scrupulously rendering small elements of foliage to describe each species’ habitat. Heade’s subjects are set against nebulous backdrops, providing vague indications of forested hills and crepuscular, clouded skies. The indistinct character of Heade’s backgrounds attests to a clear problem for these 19th-century Americans. Consider Church’s View on the Magdalena River and South American Landscape (both 1857), lavish and picturesque landscapes wherein rivers and forests are excessively abundant, and culture is rendered as eternally premodern. Both artists traveled from the United States to recently colonized locales (Brazil for Heade, Colombia and Ecuador for Church), yet they disregarded any signs of contemporaneity. Conveying their subjects in an idyllic state that invites expropriation, Heade and Church’s works are themselves evidence of a distinctly Western and capitalist view of the Global South.

Martin Johnson Heade, Hooded Visorbearer, c. 1863 – 1864, oil on canvas, Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas [courtesy of the Cummer Museum of Art & Gardens, Jacksonville, FL]

To the exhibition’s credit, the inclusion of contemporary works in Cross Pollination underscores this critical view of America’s most vaunted 19th-century landscape painters. Vik Muniz’s Orchid and Three Brazilian Hummingbirds (2013) is a digital print of a collage appropriating Heade’s Orchid with Two Hummingbirds (1871, also on view). Muniz’s aggregate of texts and images cut from mass media reads as an approximation of Heade. Upon close inspection, though, carefully selected imagery cuts through: pieces of human and animal bodies; similarly scattershot bits of lush landscapes; and, at the lower left, groups of hikers (all seemingly White) moving through dense surrounds. Muniz’s work reminds us that, despite Heade and Church’s most exacting tendencies, any representation of the natural world is a cultural construct. Other works in the exhibition advance this premise. Roxy Paine’s Bad Lawn (1998) is a broad life-sized model depicting a landscape of weeds, mushrooms, mud, and muck. The sculpture is set at waist level and is presented as if cut and removed, undisturbed, from the land itself. It’s all synthetic, of course, and such a facsimile of those miscreant species, despised in a suburban lawn, instead invites careful study of dandelions in the way that Heade considered rare hummingbirds.

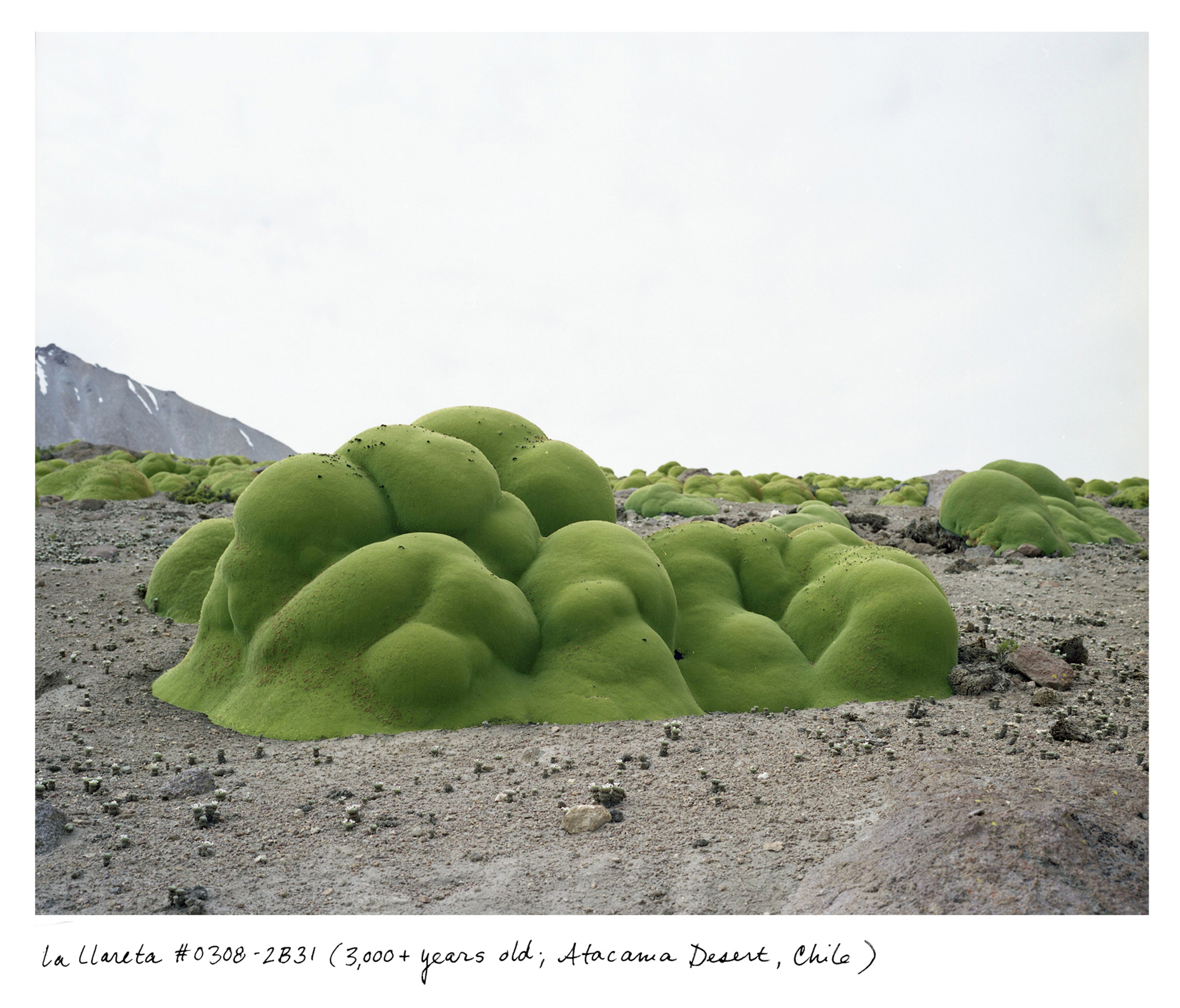

As with Paine’s sculpture, there are numerous artworks in the exhibition that emphasize the continued value of what art historian Janice Neri calls “specimen logic.” Several photographs from Rachel Sussman’s documentary series The Oldest Living Things in the World (2014) are included; as is Patrick Jacobs’ alluring diorama Pink Forest with Stump (2016); and a selection of Paula Hayes’ hand-blown glass vessels, each acting as a terrarium for gems and minerals.

More compelling are those works that not only redouble the logic of their forebears’ views on nature as artifice but call to mind the entanglements of culture and nature. Lisa Sanditz’s Laptoplegzebramussels (2016) covers a white MacBook with ceramic renditions of invasive zebra mussels, all of which are balanced atop a collapsed ceramic vessel from which a single, all-white, slacks-and-shoe-dressed leg appears. The sculpture is on-the-nose (technology as the preeminent invasive species of our time) as it comedically indicts White capitalism’s culpability in ecological collapse. Jeffrey Gibson’s Camouflage (2004) is a fluorescent and bedazzled sendup that targets the myth-making exoticism of Heade and Church. The canvas depicts a tropical canopy, but the surface is covered with silicone, beaded, piled, and scraped. In a variety of shimmering and brilliant hues, these parasitic and plastic additives build upon the structure of Gibson’s landscape, while they also grow atop and out of the painting’s very structure. A painting in masquerade, it has a title that’s a reminder of all that this exhibition’s 19th-century exemplars failed to see.

Rachel Sussman, La Llareta #0308-23B31 (3,000+ years old; Atacama Desert, Chile), 2008, archival pigment print, collection of James Tung [courtesy of the Cummer Museum of Art & Gardens, Jacksonville, FL]

As much as Cross Pollination establishes a dialogue between the 19th-century conservation movement and 21st-century deliberations on the Anthropocene, an intervening century is almost absent here. In fact, the only works dating from the 20th century also constitute the most subtle and poignant critique of Heade and Church’s colonizing gaze. Emily Cole (Thomas’ daughter) and Isabel “Downie” Church (Frederic’s daughter) are represented with numerous botanical studies. Emily Cole’s porcelain works—a tea service (1900) and Magnolia Plate (1910)—trouble her father’s conception of the natural world as Edenic, ahistorical, and awaiting a savior. Emily Cole’s porcelains suggest that a break from this narrative might entail a departure from painting (which is so bound to Western standards, and unseen in Cross Pollination, apart from the 19th-century selections) to convey how our image of nature is bound to consumption and the excesses of capital.

Cross Pollination: Heade, Cole, Church and Our Contemporary Moment, installation view, 2020-2021 [photo: Doug J. Eng; courtesy of the Cummer Museum of Art & Gardens, Jacksonville, FL]

Cross Pollination: Heade, Cole, Church and Our Contemporary Moment, installation view, 2020-2021 [photo: Doug J. Eng; courtesy of the Cummer Museum of Art & Gardens, Jacksonville, FL]

Cross Pollination: Heade, Cole, Church, and Our Contemporary Moment will be presented simultaneously as one exhibition at Olana State Historic Site in Hudson, NY, and the Thomas Cole National Historic Site in Catskill, NY, from June 12 to October 31, 2021.