Creating Matter: The Prints of Mildred Thompson

Share:

Mildred Thompson’s life traced a wandering orbit. Born in Jacksonville, FL, in 1936, she attended Howard University in Washington, DC, and trained at the Art Institute of Hamburg, Germany, before returning to the United States in 1961, where she spent several years trying to launch her career in New York. Although she had works acquired by the Museum of Modern Art and the Brooklyn Museum, many galleries declined to show work by an African American woman. One owner suggested that she find a white woman to represent her publicly. Other black artists working in abstraction faced similar barriers in all directions. As Howardena Pindell recounted in a 2014 interview with Artnews, “I remember going with my abstract work to the Studio Museum in Harlem, and the director at the time said to me, ‘Go downtown and show with the white boys.’” Thompson, who identified as a peripatetic citizen of the world, instead left for Germany again, this time to teach at the Volkshochschule Eschweiler until moving back to the United States in 1974. She made stops in Florida–Jacksonville and Tampa–before settling in Atlanta in 1985, where she worked as an associate editor of ART PAPERS from 1987 into the early 2000s. She continued to show in the US and Germany until her death in 2003.

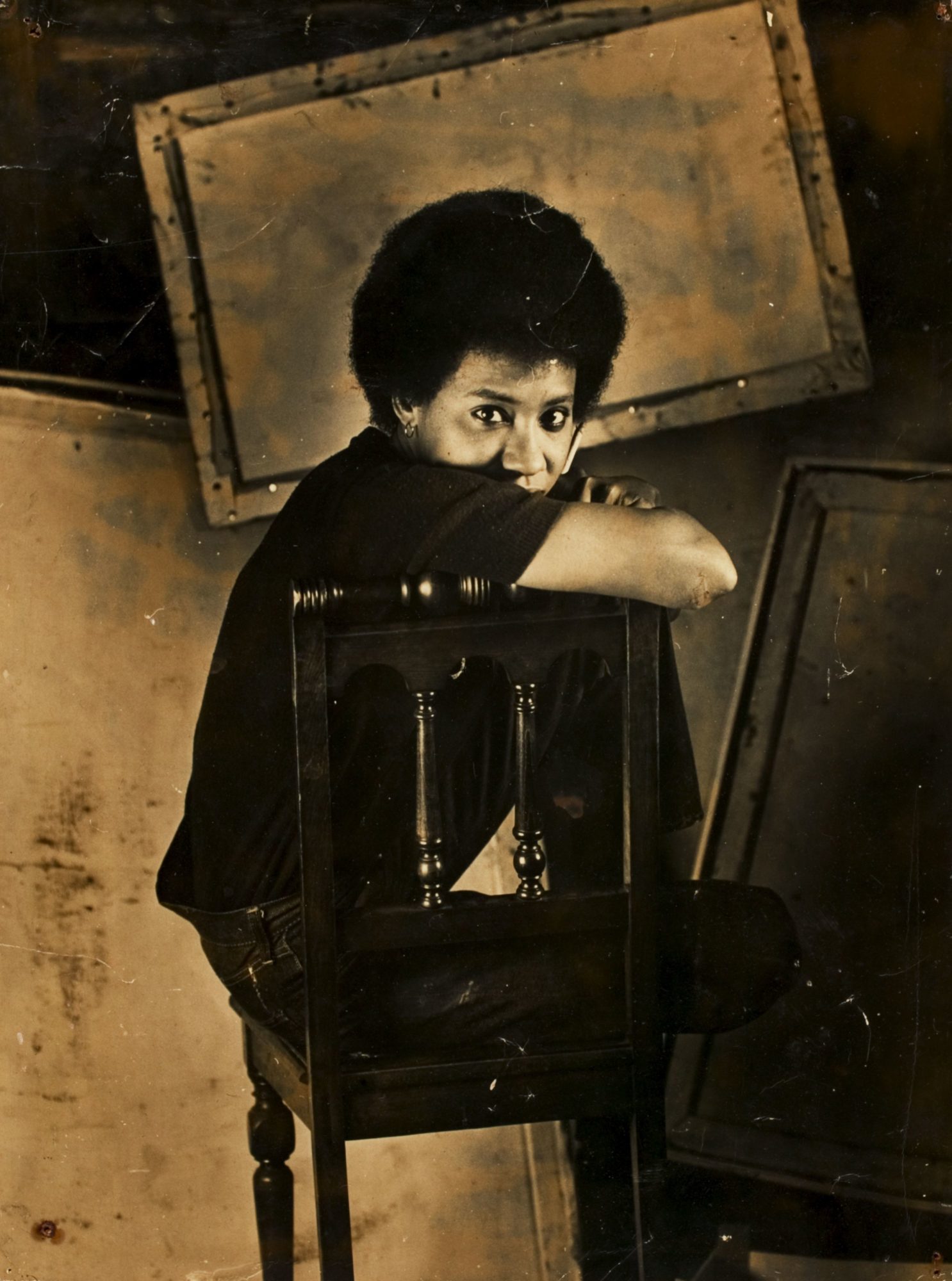

Portrait of Mildred Thompson, c. 1960s

[courtesy of the Mildred Thompson Estate]

At the Michael C. Carlos Museum of Art, Creating Matter [January 17–May 17, 2015] features 18 of Thompson’s works on paper. An untitled etching from 1959 provides a hint of her early trajectory as an artist. It centers on a shadowy female figure with raised arms surrounded by a welter of scratches, dots, arcs, and blotches. This subject’s serene face is a still white oval that floats above the jostling marks that fill the margins—marks neither clearly regimented enough to be symbols, nor depicting anything as definite as a scarred background surface. They are, rather, like unstructured graphical scraps, dancing bits of visual matter that have not yet cohered into anything solid.

This early piece, along with Love for Sale—a 1959 etching in the collection of MoMA—aligns Thompson stylistically with Jean Dubuffet. In the later works on view, Thompson abandons the figure, allowing the restless patterns of marks formerly of the surrounds to come to the fore. Her images were often inspired by her readings of modern physics and cosmology, as well as the mystic P.D. Ouspensky’s writings; some incorporate visual allusions to specific scientific phenomena. Her scratchy arcing lines resemble tracks of ionized particles in a cloud chamber, and the Caversham Press, South Africaseries (1999) includes a repeated central design that is reminiscent of the bipolar radiation burst of a pulsar, or ejection jets streaming from a black hole.

Although Thompson drew inspiration from her study of physics, a heavy-handed reading of these works in terms of physical theories or technical methods of visualization would overstate their connections with the science and downplay the strengths of the works. The marvelous vitrograph Wave Function III (1993), despite its titular nod to quantum mechanics, shows a dynamic world of vortices and flow in which yellowish discs swirl above thick, sinuous, black waves in a sea-blue background. Its lines, dots, and swirls suggest endless processes of seeking form rather than settling into it. Advancing Impulses 36 (1989) features a seething, brightly colored ribbon of streamers that curves its way across the page in a shape-shifting mass. Its entangled forms depict a sequence of transformations encompassing a process of continual creation and destruction. The print echoes works by Alma Thomas, particularly The Eclipse (1970), with its tiled circular patterns of nearly square elements forming a burning corona.

For Thompson, then, science is a source of metaphors and basic elements (fields, waves, and strings) for depicting processes of all sorts. Even her landscape-themed works have a tightly wound energy to them. In the barren world of The Fourth Mystery (1989), a circle of negative space hovers above a crooked horizon line and a sky filled with streaks and shards of matter, making the ground appear to be coming apart at the seams. In other works this process of unraveling is nearly complete: by The Fifth Mystery (1989), the solid earth has vanished entirely, replaced by chaotic clouds of torn-looking remains. Thompson returns repeatedly to the dual nature of material transformation (another series on view is aptly titled Death and Orgasm), but in these darker, explosive works its destructive aspects are dominant, as opposed to the joyfulness that overflows the larger color prints.

In addition to being a printmaker, Thompson was a painter, sculptor, and blues musician. Though her last major retrospective was almost two decades ago (Mildred Thompson: Deep Space, Jacksonville Museum of Contemporary Art, 1997), even this small selection of her works excels in highlighting their restless exuberance, and the varied ways in which she captured the unceasing cycles of change that drive the material and spiritual worlds. Creating Matter makes a strong case for a more comprehensive reassessment of her place in the history of contemporary abstraction.