Counterpublic 2019

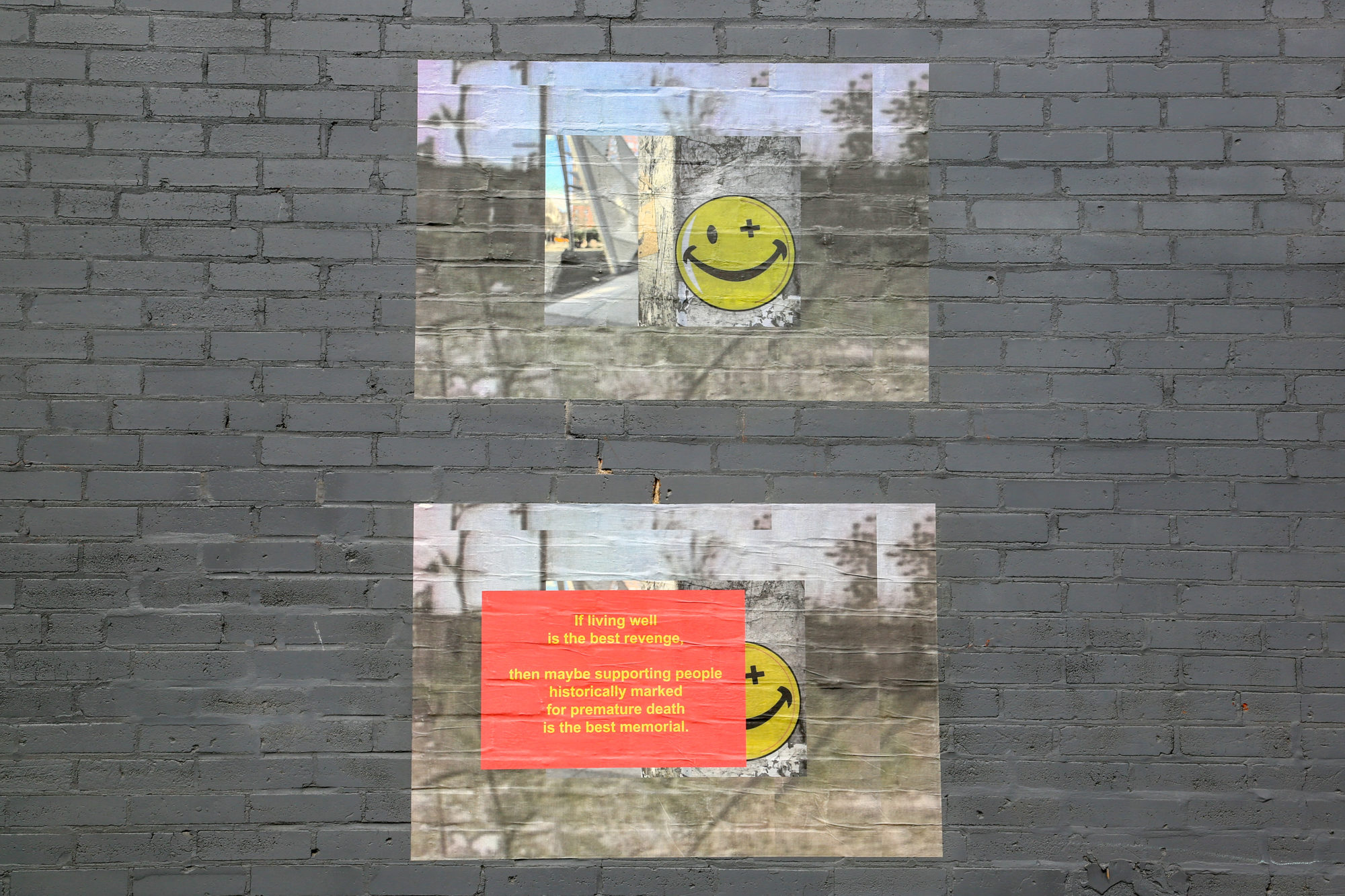

Thomas Kong, Be Happy, installation view at The Economic Shop [photo: Melissa Fandos; courtesy of the artist and The Luminary]

Share:

Late afternoon sunlight floods in, through a garage door that opens into a local yoga studio, where Isabel Lewis sways in front of a makeshift DJ stand. She is conjuring music that pulses into the intimate space outfitted with large plants where one of her “occasions”—a hybrid social event merging spoken address, movement, music, scent, and taste—is just getting started. Like many of the projects in Counterpublic 2019, the unconventional site enhances the event’s reception by its public. Arriving to a casual, and sort of unusual, yet energetically charged yoga studio alleviates the formalities that often create psychic boundaries between performer and audience (or artwork and viewer) in a conventional theater or museum. With those delineations off the table, Lewis is a conductive force as she enacts her stated role as “host.” Rather than watching passively, everybody in attendance is invited into the collective production of this affective space as an active participant.

Over the next four hours, guests breezed in and out with comfort, moved to Lewis’ music, and socialized. The evening was punctuated by Lewis’ movement scores and spoken addresses, during which she evoked the rational and desirous structures of love brought forth in Plato’s Symposium, and meditated on models of radical receptivity stemming from Martha Nussbaum’s theory of love as a critical form of knowledge. She passed around small glass bottles containing custom scents designed to represent intangible qualities such as “intellect”; interacted with the plants in the room (even giving one voice by holding a microphone to its roots, which triggered mysterious audio-feedback); asked guests about their gardens; and mused about how tending to relationships—like tending a garden—is a way to reconnect, or interrelate, with each other, other species, and things. Seamlessly integrating sound, scent, movement, taste, and theory to be absorbed by the guests, Lewis conjured a space that enacted the principles of interconnection, receptivity, cultivation, and love that she imagines in her spoken address. Refreshingly, it didn’t look like performance. It felt like communing—something that everyone in the room took part in creating, and tending, together.

Azikiwe Mohammed, Armor Photo Studio, installation view at Blank Space [photo: Melissa Fandos; courtesy of the artist and The Luminary]

In this way, Lewis’ occasion expressed some of the central concerns, modes of approach, and imaginative potentials of Counterpublic 2019. The inaugural St. Louis triennial public art platform took place on a highly localized scale—a 12-block radius around a neighborhood known as Cherokee Street. Curated and produced by the arts organization The Luminary (whose gallery space is located on Cherokee Street), the triennial occurred over the course of three months from mid-April through mid-July, embedding projects at sites across the neighborhood. The area is home to mostly black and Latinx populations, and its businesses are majority Latinx owned and operated. It continually contends with new development as well as layers of social and economic variation, and its namesake indicates even deeper wounds of suppressed indigenous histories. The platform is designed to respond to the activities, histories, needs, and imagined futures of the immediate neighborhood, echoing forth to consider St. Louis as a city historically—and currently—activated by community organizing, conflicted politics, and major protests.

More than 30 local and national artists were commissioned to produce projects that engage with the site and the community, and reexamine history to emphasize “dissent, dialogue, care, and complexity” within spaces that the immediate community might use, see, or interact with on a daily basis. Artists’ projects are situated in sites where one wouldn’t expect to encounter artwork—such as a panaderia, an auto body shop, a convenience store, breweries, and thrift stores—in addition to occupying public spaces such as vacant lots, streetlight banners, storefronts, and the streetside garden of a Buddhist temple, refiguring the terms of viewership and artistic practice as expansive and embedded, and often unrecognizable as artwork.

Some of the most delightful and impactful consistencies of Counterpublic were the ways in which artworks and interventions were so wholly absorbed into the vernacular of their given sites. The quiet, understated nature of this artistic intervention meant you might not register an artwork unless you are really looking for it. Even then, you might miss it. With my wayfinding map in hand, actually locating the works was like going on a treasure hunt that demanded a particular attentiveness to the nuances of the neighborhood and individual local businesses. A convenience store called Economic Shop housed an installation of collages made by Thomas Kong from the discarded packaging of products sold within the store, colorful compositions that value the makeshift materials at hand. It’s easy to miss Kong’s works lining the walls and shelves, but all customers received an artist-decorated shopping bag with their purchases, carrying part of the project home with them. Rodolfo Marron III’s work occupied Diana’s Bakery, a panaderia where colorful galletas were customized by the artist with phrases celebrating Latinx diligence and resistance—such as “Aqui Estamos”—blended in amid the other sweets in the shop. Although the economic impact of situating projects in small, local businesses is intangible (I felt compelled to purchase a small item in many of the shops I visited), proceeds from the sale of these galletas go to the immigration advocacy group Latinos en Axión, directly channeling funds to a community entity.

Theodore Kerr, WHERE IT STARTS, installation view [photo: Melissa Fandos; courtesy of the artist and The Luminary]

Like Marron’s galletas, Counterpublic privileges projects that function as resources, organizing efforts, and community engagement. Many of the projects by design take various temporal and social registers; unfolding over the course of three months, the scope of this triennial cannot be experienced in its entirety by a lone visitor. Theodore Kerr’s posters, wheatpasted on the exterior of The Luminary, used layered images to visualize entanglements between AIDS and race. The works are based on research around Robert Rayford, a young St. Louisan identified as one of the earliest people living with HIV in the US. Kerr’s project extended deeply into the community. Although I was able to spend time with the posters, I was present at neither the numerous workshops and public conversations that he facilitated, nor at the co-hosted nonpublic working sessions for people living with HIV in the area. For Azikiwe Mohammed’s Armor Photo Studio, the artist spent a month operating out of a community space on Cherokee Street to provide visitors with free portraits as part of an ongoing project to offer tangible forms of self-representation in communities not typically depicted positively—or in some cases at all. Going beyond the scope of his studio hours, Mohammed also traveled around the city to serve residents who couldn’t make it to the studio, to ensure representation for those who wouldn’t otherwise have access to his portraits. Digital Margins, a collective library designed by Jerome Harris, Serubiri Moses, and Gee Wesley, amplifies marginalized voices on the Internet. Tucked away in the back of a tea and smoothie shop, the library has a copy machine and bookbinding tools, encouraging visitors to reproduce and take resources home with them. The ever-evolving and sometimes hard-to-see nature of Counterpublic emphasizes its stakes: it is designed to serve the place and community from which it is cultivated and with which projects develop. With only a weekend on Cherokee Street, I felt as if I had seen only a fraction of this expansive project, and I left St. Louis with a desire to return there and see how projects shift, evolve, and continue to extend their reach.

Driving the triennial—as indicated by its name—is the urgent question of publics: what constitutes a public and how can alternative publics be formed? Temporary publics were built and questioned through a host of events aimed to cultivate new social spaces that will inevitably have a range of individual, social, and collective impacts beyond the scope of the triennial. Jeremy Toussaint-Baptiste’s sonic installation Get Low, designed specifically for people for whom visibility can be burdensome, had an ongoing presence in the St. Louis Hop Shop—an intimate, dark, and sonically resonant place where one could escape visibility and the psychic demands of being in public space. Cauleen Smith’s powerful film Sojourner—on view in a repurposed church basement—conjures imagined worlds. The film ties together historic and imagined social spaces such as Alice Coltrane’s Ashram and Noah Purifoy’s built universe in the desert to imagine affirmative black futures.

Rodolfo Marron III, Aquí Estamos – Estamos Aquí, installation view at Diana’s Bakery [photo: Brea McAnally; courtesy of the artist and The Luminary]

In the nave of that church, a commanding and meditative installation of processual banners from Sojourner bearing Alice Coltrane lyrics hangs overhead. I visited this installation with one of Counterpublic’s curators, Katherine Simóne Reynolds. Standing beneath these banners, I overheard her respond to another visitor, who inquired about her perception of the “success” of Counterpublic. Gracefully challenging the notion of quantifiable success, Reynolds responded that the value in producing Counterpublic was not in whether it was “working” but rather what participants were learning from the process, and that they were learning. This exchange articulated Counterpublic’s ethos of learning from the triennial’s (and The Luminary’s) many publics, as well as alongside them. Both the inquiry and Reynolds’ reply resonated with the project’s position that here, artwork functions to cast attention toward people and place; to foster relations with multiple publics; and to build a new, alternative future and, indeed, counter-publics.

The myriad forms that Counterpublic takes manifest in subtle, often tender, everyday activisms that reorient focus onto site and community, unexpected social exchanges, and the cultivation of new publics, catalyzed by each artistic gesture. If Counterpublic aims to examine, engage, and shift the conditions by which community is built and lived on a daily basis, then these quiet provocations permeate the area in ways that have affective, maybe even unconscious, impacts on those whom they touch.

Alexis Wilkinson is a curator working across dance, performance, and visual art. She is currently the Director of Exhibitions and Live Art at Knockdown Center in Queens, NY, where she organizes interdisciplinary exhibitions, performances, and events. Her curatorial projects have been presented at SculptureCenter, NY, the Hessel Museum, NY, the Judd Foundation, NY, A.I.R. Gallery, NY, Cuchifritos Gallery + Project Space, NY, The Luminary, MO, Abrons Art Center, NY, and NADA NY. Alexis holds an MA from the Center for Curatorial Studies, Bard College and a BA in Cultural Studies, Dance, and Art History from the University of California, Los Angeles.