Constitutionally Flawed

Share:

(“WE DON’T WANT TO FORGET ABOUT HOME” is entirely universal and therefore remains untranslatable) “the translator” [who was terribly homesick even at home—the translator is without a uniform, mind you]

—Don Mee Choi, DMZ Colony

Many are flung carelessly at birth and they experience the diminishment and sometimes the pleasant truculence of their random misplacement.

—Elizabeth Hardwick, Sleepless Nights

***

In my left lung, my body calcified a particle so that I carry a pea-size bone stuck inside the organ’s soft tissue. A doctor speculates that it might have been a small particle of tuberculosis I encountered as a baby or toddler; my body wrapped and ossified it to protect itself.

In 1980, the year I was born, Argentina and most of its bordering countries shook under murderous dictatorships, in what was known as Plan Cóndor, a military effort backed by the US government, with the objective of eradicating communism and leftist movements in South America. Policemen and soldiers were making civilians disappear, and exile was common. After my aunt, a communist leader, was detained and nearly “disappeared,” my parents fled to Brazil, where I grew up for four years. Before I started elementary school, they decided to move back to Buenos Aires, and they split. When I opened my mouth, words in Portuguese came out. The curiosity this produced in others made me shy. It is likely that I blushed. I know I went silent for three months, as my brain and tongue were transformed from Portuguese to Spanish.

Places and people do not last. Animals: They do not last. A beginning, a spark, movement, evanescence. Time passes, history builds and builds, people, animals, particles become invisible inside the length of history, even as they form it. A transformation from a blank page to an image to a blank page to language to a blank page to a story to a blank page to abstraction.

Upon returning to Argentina my young parents got busy with the liberations of democracy, such as drugs, free love, and new age pursuits. My mother joined a Chilean guru who had people call him Awankana. He had a “natural life” retreat called La Villa funded by well-off families. La Villa was a place to have fasts and other Westernized Zen experiences. They allowed a few people from the lower classes, including my mother, to join, proving that they did not lack a charitable spirit. Awankana would assign a woman to make the meals for him, and his wife and child, for an undetermined length of time.

In 1980, the year I was born, a referendum in Chile replaced the constitution of 1925 with a new one that allowed Augusto Pinochet, the dictator, to remain in power. The—probably fraudulent—referendum took place in the middle of Pinochet’s dictatorship, which started in 1973 with the military’s bombing of the building called La Moneda, the seat of the presidency, and would last until 1990.

In 1973 the President of Chile was Salvador Allende, the first Marxist to be democratically elected to any government in the Americas. Allende’s years as president were defined by resistance from the conservative sector in alliance with the foreign affairs services in the United States. On September 11, 1973 while La Moneda was under military attack, Allende released a radio message addressing his supporters. After the call, he shot himself in the head and died, before soldiers were able to make him a prisoner of war.

In my grandmother’s house, on the wall of a long and narrow hallway, was a photo of Salvador Allende hugging Pablo Neruda. It hung salon style amid other photos and prints that portrayed Che Guevara, Fidel Castro, Silvio Rodríguez, Víctor Jara, Violeta Parra, Frida Kahlo.

When I knew only how to crawl, I climbed a set of stairs to a terrace while my parents rehearsed a theatrical play with their friends. At the top of the stairs was a chair. I grabbed it to balance myself in a standing position, and I tripped and fell down the stairs, dragging the chair with me. The chair hit my forehead, and a big wound opened, washing my face in blood. Except for menstruation, seeing my own blood made me faint well into my 20s.

Cecilia Vicuña, a Chilean artist and poet, was exiled to London during the Pinochet dictatorship. In 2010, at the Native Spirit Festival, she ended her performance with the following:

Invención de la escritura por la luna

This is the story of a myth. I can’t remember where I read it, but I know where I changed it around. In this story people say that nobody really listens to Jesus Christ so Jesus Christ pleads to the moon, “Please make them listen.” So she menstruates in response. Her blood falls to the earth, becoming the first script. Her blood causes a page of scripture to fall to earth. This is the birth of writing. Writing is menstrual blood pouring down the legs. The first script: show my blood, show my blood. The moon teaching Christ, see? This is how you read the script. The thighs.

When I am blushing, it feels like my blood boils upward from my neck toward my forehead. I can blush out of surprise, shyness, embarrassment, anxiety. Certain people make me blush from discomfort, others because they give me a level of enjoyment that feels transgressive. Do not comment on my blushing. That will feel cruel to me and will only make it boil hotter. When I laugh hard, I cry.

In 2004 I left Argentina to live in the United States. After a short visit in 2007, I did not return to Buenos Aires for 11 years, because my family ties were so strained that they snapped. After study and immersion, my brain and tongue acquired English. I started to inhabit a layered existence wherein the languages and geographies that compose me were overlapping with one another, sometimes in dissonance, sometimes in harmony.

In 2017 I led a group of college students in a course about Chilean art and poetry to Santiago and Valparaíso for eight days. I had not been near that latitude for a decade. We visited Manuel Paredes Parod, a man who survived three months of detention not long after the Pinochet coup. Manuel received us on his patio, amid his plants and bird fountain, a grapevine, an orange Volkswagen bus, and a telescope. He told us that when he was in detention, the prisoners quickly organized a makeshift school to teach one another mathematics, history, and philosophy. They made chess pieces out of breadcrumbs to play. They secretly carried water in their mouths, past the guard, to give it to a man so beaten up he could not leave the common cell. The moment Manuel remembered as the saddest in his whole life was hearing a baby cry of hunger outside his cell while an old man rejected a ration of milk in protest. The first night after Manuel was released, he defied the curfew to go write “Viva Allende” on a wall in Santiago.

Pablo Paredes, a poet and political activist, is Manuel’s son and my friend. In a conversation, he mentions Gabriela Mistral’s “Menos cóndor y más huemul,” about the two animals in Chile’s coat of arms. The words “por la razón o la fuerza” (by reason or by force) appear on a ribbon at the bottom of the heraldic image. The huemul, a type of small deer native to Chile and Argentina, stands for reason, the condor for force. As the title suggests, Mistral favors the huemul because of its grace and its method of avoiding enemies, which involves smelling them before they come near. Mistral points out that birds of prey are too ubiquitous in heraldry as symbols of power. She praises the huemul as a representation of human attitudes like being pacifist—soft in our expressions, words, and actions—and hospitable; she urges people to behave like the huemul, and like a condor only to take flight, over great precipices of danger.

After my decade of absence from Buenos Aires, the way Manuel, Pablo, and other friends spoke Spanish sounded like a form of home. They rejoiced in my Argentine accent and slang as much as I did in their Chilean cadence and rhythm. The neoclassical architecture in Santiago resembled that of my city. The afternoon light hit both places with the same tonality and slant. Walking around Santiago reminded me of Buenos Aires so much that I burst out crying in the street.

In Valparaíso my hotel room was on a high floor, with a view of the port. I looked at the ocean and had a moment of delirious buoyancy. My body turned inside out as I exited through my eyes, becoming attached to the surface of the moving mass of blue water.

In 2018 I finally returned to Buenos Aires. The city was rundown and gritty, after what my uncle Rubén, exiled to Mexico by the recession in Argentina, calls “too many crises.” My close family was as dysfunctional and problematic as always. The place was marvelous and disappointing. I missed Santiago.

I traveled to Chile with different groups of students three years in a row. Manuel received us in his home every time, even on our last trip in March 2019, when he had been diagnosed with colon cancer. In a voice message, he said “Tengo la vida hecha” (“My life is complete”), reassuring me that he was satisfied with what he had lived, and with his present. A few months later I received a message from Pablo announcing that Manuel had died.

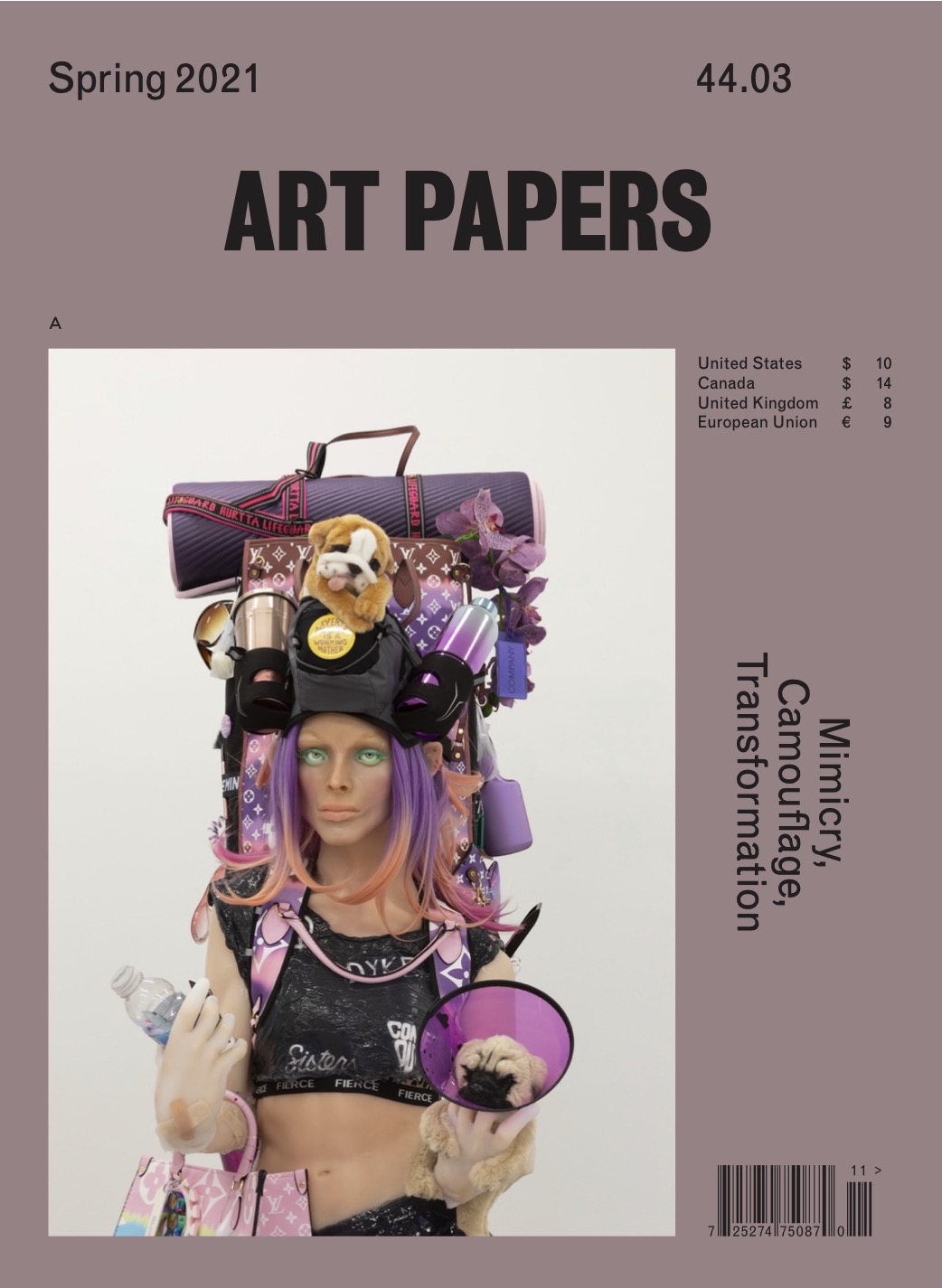

María Korol, Constitutionally Flawed, 2021, digital sketch for stop-motion animation [courtesy of the artist]

In 2019, after the subway ticket fare was raised, high school students started jumping turnstiles in Santiago. Their action would grow into “el estallido social,” a social eruption: massive protests about the cost of living and inequality that culminated in a collision between civilians and law enforcement. The extreme neoliberal economics of the dictatorship had created great financial growth, badly distributed. El estallido took a clearer form and direction as protesters demanded constitutional reform. After postponement caused by the pandemic, a referendum took place on October 25, 2020. Almost 80% of Chileans voted in favor of a new constitution for Chile, rejecting the remains of authoritarian rule.

In the United States in 2020 we had our own “estallido social,” after a Minneapolis policeman killed George Floyd. The country had been experiencing heightened stress for the previous four years under the inept leadership of a president whose main expertise was fueling racist, xenophobic, and sexist tendencies in his supporters. The reality of a double pandemic—institutionalized racism and coronavirus—in the United States is a harsh one.

A few weeks after the pandemic was officially declared and students were sent home, I needed to run an errand at the college where I was teaching. I was sitting by a copy machine and doing work on my laptop when a young campus policewoman walked by, headed to the bathroom. On her way out, she stopped to ask me if I were a student. I said no, I was faculty. She said she detected an accent in my speech and asked me where I was from. I said, “Argentina.” She asked me if I was a United States citizen. With my eyebrows raised I said yes. She asked herself aloud whether it was one of her duties to refer to ICE someone who was illegal in this country, and responded to her question: “Maybe, but I wouldn’t do it!” She looked at me with one filmy eye and the other straight out shining.

Is it possible that the architecture of our bodies—two eyes, two nostrils, two ears, two hands, two feet—might have something to do with a tendency to organize everything into pairs and binaries? Inner and outer parallels and symmetries, right and left, high and low, north and south, male and female, good and bad, white and black, on and on, binaries begetting hierarchies. When the gradations of the in-between are obscured, we circumscribe ourselves to a small, fenced perimeter. As we delineate it, we fail to perceive or understand any shape that lies outside, especially if it refuses a simplistic classification.

The new Chilean constitution will be democratic and feminist, written by equal numbers of women and men, and including the Mapuche, Chile’s largest indigenous populace. It will be the first constitution in the world to be written by an equal number of women and men. It will be written from a blank page, not as a revision of the existing articles but as a completely re-imagined document. A transformation from a blank page to an image to a blank page to language to a blank page to a story to a blank page to—

***

This project originally appeared in ART PAPERS Spring 2021 // Mimicry, Camouflage, Transformation.

María Korol’s artistic practice is rooted in drawing, and includes explorations of three-dimensional formats, interdisciplinary collaboration, and writing. She is interested in storytelling and the imagination, history and its distortions, memory and transformation. Korol has shown her work at MOCA GA and Swan Coach House Gallery in Atlanta, The Painting Center in New York, and the Akademie der Künste in Berlin, among other places. She is a distinguished fellow of the Hambidge Center, the JUNGE AKADEMIE, and the Women’s Art Institute. She is the recipient of the 2020 Forward Arts Foundation Edge Award. Based in Atlanta, she is a visiting assistant professor of art at Morehouse College.