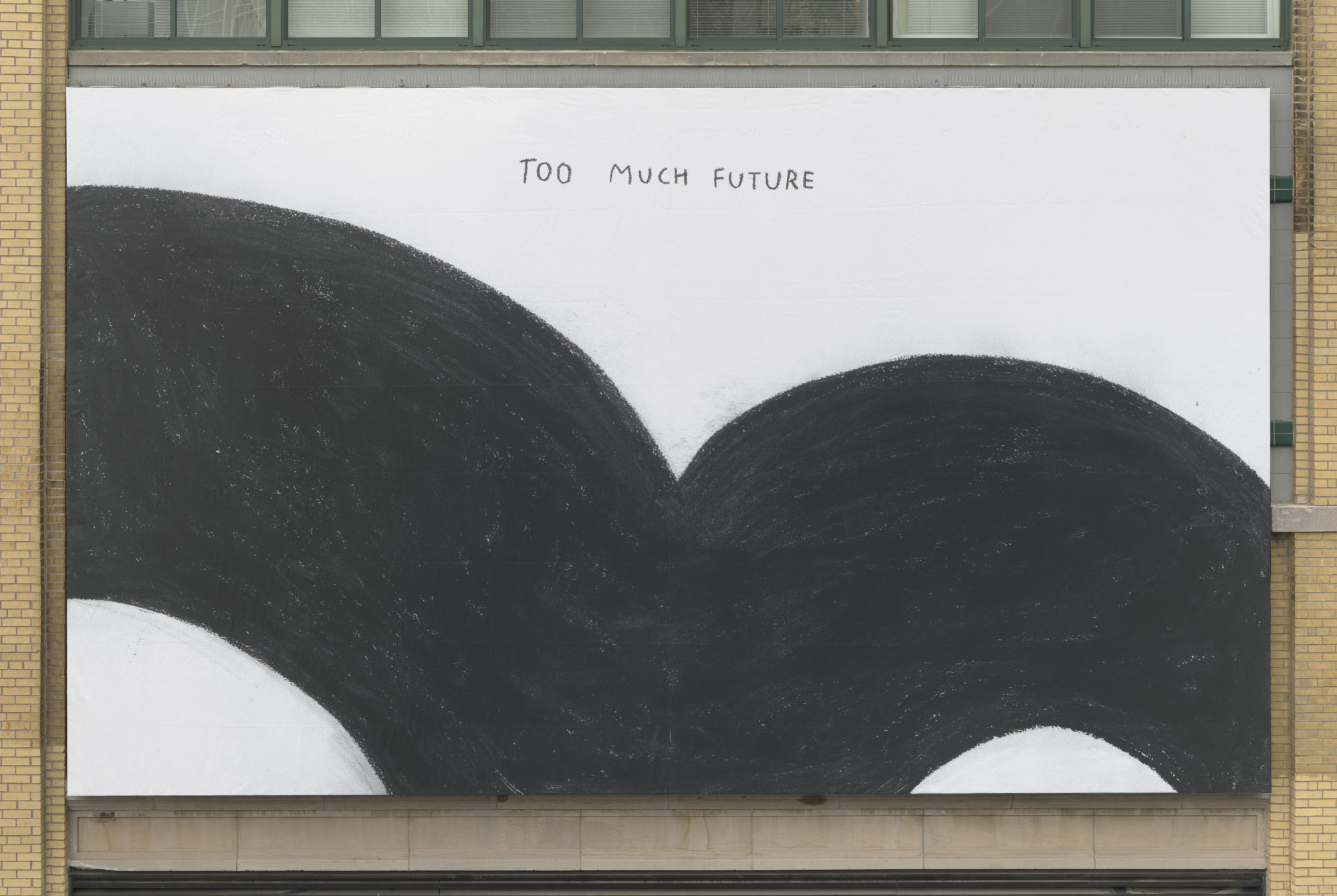

Christine Sun Kim: Too Much Future

Christine Sun Kim, “Too Much Future,” 2017 [photo: Ron Amstutz; courtesy of the artist and the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York]

Share:

Nina Sun Eidsheim’s 2015 text Sensing Sound: Singing and Listening as Vibrational Practice sits at the fore of recent scholarly interventions—in musicology, sound studies, and elsewhere—premised on a relational and embodied new conception of the sonic. Sensing Sound critiques what Eidsheim calls the “figure of sound”: a reductive set of tropes according to which we understand sound and music as knowable a priori, given to easy abstraction, and, often, purely auditory. Taking a cue from anthropologist Clifford Geertz’s noted technique of “thick description,” which invites the close interrogation of any cultural event’s contextual tissue, Eidsheim counters the staid figure of sound with a “thickened” conception of sonic and musical practice insistent upon sound’s ecstatic slippages across different sensory registers (auditory, visual, and haptic) and between different people and things.

I thought of Eidsheim’s thickened notion of sound while meditating upon artist Christine Sun Kim’s 2018 billboard installation for the Whitney Museum of American Art: a large-format charcoal drawing titled Too Much Future. A scaled-up treatment of a smaller drawing originally executed for the 2016 Shanghai Biennale, Too Much Future, prominently placed outside the Whitney, greeted viewers descending from the High Line with a bold, black, and thick visual interpretation of the American Sign Language (ASL) sign for the word future.

One can sign the word future in ASL by drawing a hand away from the face in an arc-like motion, but of course, the gesture is far from fixed. As Kim notes in a March 2018 interview with Sean J Patrick Carney for Humor and the Abject, “When you sign ‘future,’ you use your face to add texture and mood to it. Even to describe its size. I love how you can tweak your face just a bit to radically alter the meaning.” The thick rendering of future that cuts across the Whitney billboard exploits ASL’s capacity to differently communicate size and texture. It finds Kim, as usual, wringing powerful evocation from the “tweaks” that smuggle themselves into our interactions.

A monument to the depth and complexity of communication, as well as “a tribute to ASL” (as Kim said to Carney), Too Much Future presents an entry point into the artist’s widely varied practice, which is never too distant from sonic concerns, but also encompasses drawing, sculpture, video, and performance. Over the past decade, Kim’s mercurial, playful body of work has made progress in undoing tidy understandings of the senses that can serve to exclude and obfuscate. At root, Kim’s work surrounding sound concerns itself with the social, visual, and textual-notational codes that bracket sound as traditionally understood, bringing it well beyond the domain of what is “heard” (the auditory) to expose the artifice and impoverishment lurking behind such a category.

Christine Sun Kim, “Too Much Future,” 2017 [photo: Ron Amstutz; courtesy of the artist and the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York]

For 4X4 (2015), an installation developed for the Stockholm venue Andquestionmark, Kim used four large subwoofers to play back four songs—composed by the artist, and performed by Tony Conrad, Matana Roberts, Jeffrey Mansfield, and Robert Cohn—pitch-shifted into the 7–35 Hz range. Although 20 Hz is generally reported to be the lower limit of human hearing (and here we might be wary of such rigid codification), infrasound, as lower-frequency sound is termed, offers itself viscerally to nonauditory senses. Visitors to the one-night installation saw and felt the songs as they rattled and rippled through the venue’s architecture, stimulating the room’s resonant frequencies. As Kim has remarked to Jeffrey Mansfield for Coronograph, 4X4 marked a powerful use of “space as an instrument.”

Kim’s more recent works, The Grid of Prefixed Acousmatics, exhibited at Dartmouth College’s Hood Museum of Art in 2017 reposition, via drawing and ceramic sculpture, composer-theorist Pierre Schaeffer’s notion of “acousmatic sound”—that is, sound that has been separated from its causal source or context and thus made reducible to a “sound object” (l’objet sonore). Cleverly “cementing sounds,” to borrow a phrase from Kim, the Prefixed Acousmatics works illustrate the acousmatic dimension of ASL interpretation. According to the artist, interpreters often don’t need to turn their heads toward sound sources. However, keeping in mind the “prefixed” aspect, which proposes a complication or hyphenation, the works also unsettle the conceptual definitions of Schaeffer’s framework, proposing that interpretation in turn produces new (visual) sources of sound.

These two projects constitute a small cross-section of Kim’s practice, but demonstrate the artist’s ongoing interest in the relays and rebounds that sound follows across different sensory registers. Kim also demonstrates a continued preoccupation with social mediation and translation—interpretive processes whereby, per Kim, one “borrows” or “inhabits” the voices of others. Although it is hardly surprising that Kim has come to be known (perhaps reductively) as a “sound artist,” the “sound” native to her practice has a shape-shifting, relational ontology, straddling all the senses and positing a proudly thickened new approach to sound art.

Kim’s work enters into compelling conversation with new theorizations of sound in sound studies, disability studies, and elsewhere. Brandon LaBelle’s new Sonic Agency (2018) asks urgently what sound might have to offer activism, resistance, and the formation of publics. Alexander Rehding and Emily Dolan’s forthcoming The Oxford Handbook of Timbre promises, in its focus on the most fugitive of musical qualities, to trouble claims of sonic “realism” that neglect social and material specificity. Mara Mills, Jonathan Sterne, and Stefan Helmreich have written extensively on sound’s technological chains of translation and the co-constitution of media and disability.

In tandem with Kim’s practice, these inquiries and theorizations offer themselves generously to anyone committed to thinking and working with sound outside the constraints of tired phenomenological and realist-scientific paradigms. These possibilities hover behind the arching lines of Too Much Future, auguring further strides toward a new sonic inclusivity.

This review originally appeared in ART PAPERS “Disability + Visibility,” Winter 2018/2019.