Chang Yuchen: Language, Use, Value

Chang Yuchen, Use Value – Mask 40 [photo: Kunning Huang; courtesy of the artist]

Share:

When I first contacted Yuchen about an interview in early March 2020, she was on her way to an artist residency at the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art (MASS MoCA). Initially I wasn’t sure how a virtual interview would play out, especially with Yuchen out of her studio. This concern turned out to be rather prophetic. Within roughly two weeks of our first contact, New York City—where we both live—had begun to rapidly shut down. Working virtually quickly became “the new normal.”

When Yuchen first arrived at MASS MoCA, about a dozen other artists were in the residency, situated in a quiet, wooded suburb of Pittsfield. After just a few days, though, only she remained. Near MASS MoCA is a clock tower that chimes every quarter hour. For Yuchen, it served as a way of marking her daily rituals, as well as a constant reminder of the passage of time. It has become overwhelmingly clear for many of us that our time is framed by our work, and how we use that time establishes a sense of worth. The idea of usefulness became a common thread throughout my conversation with Yuchen, an apt theme as we collectively examine established systems of labor.

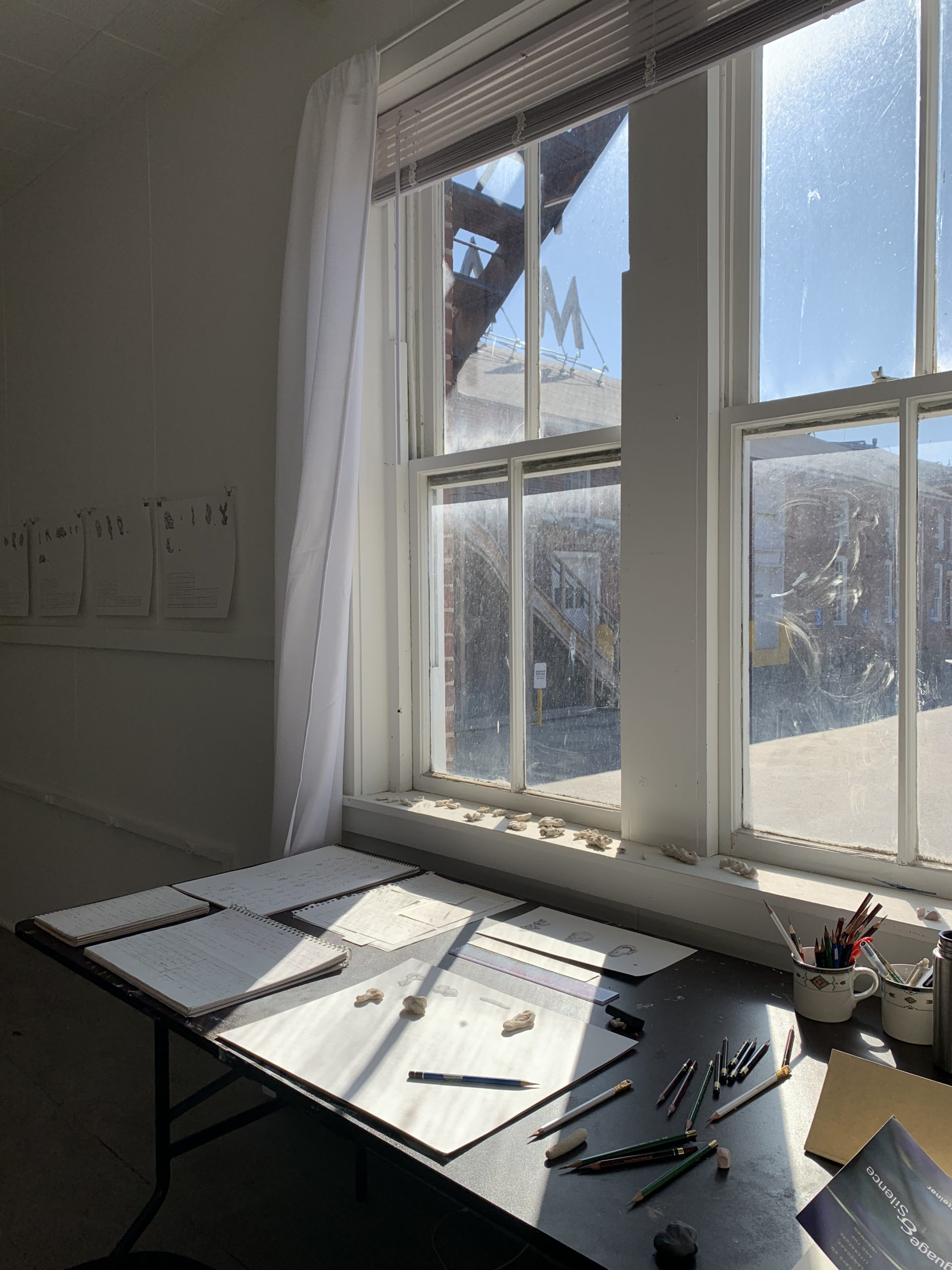

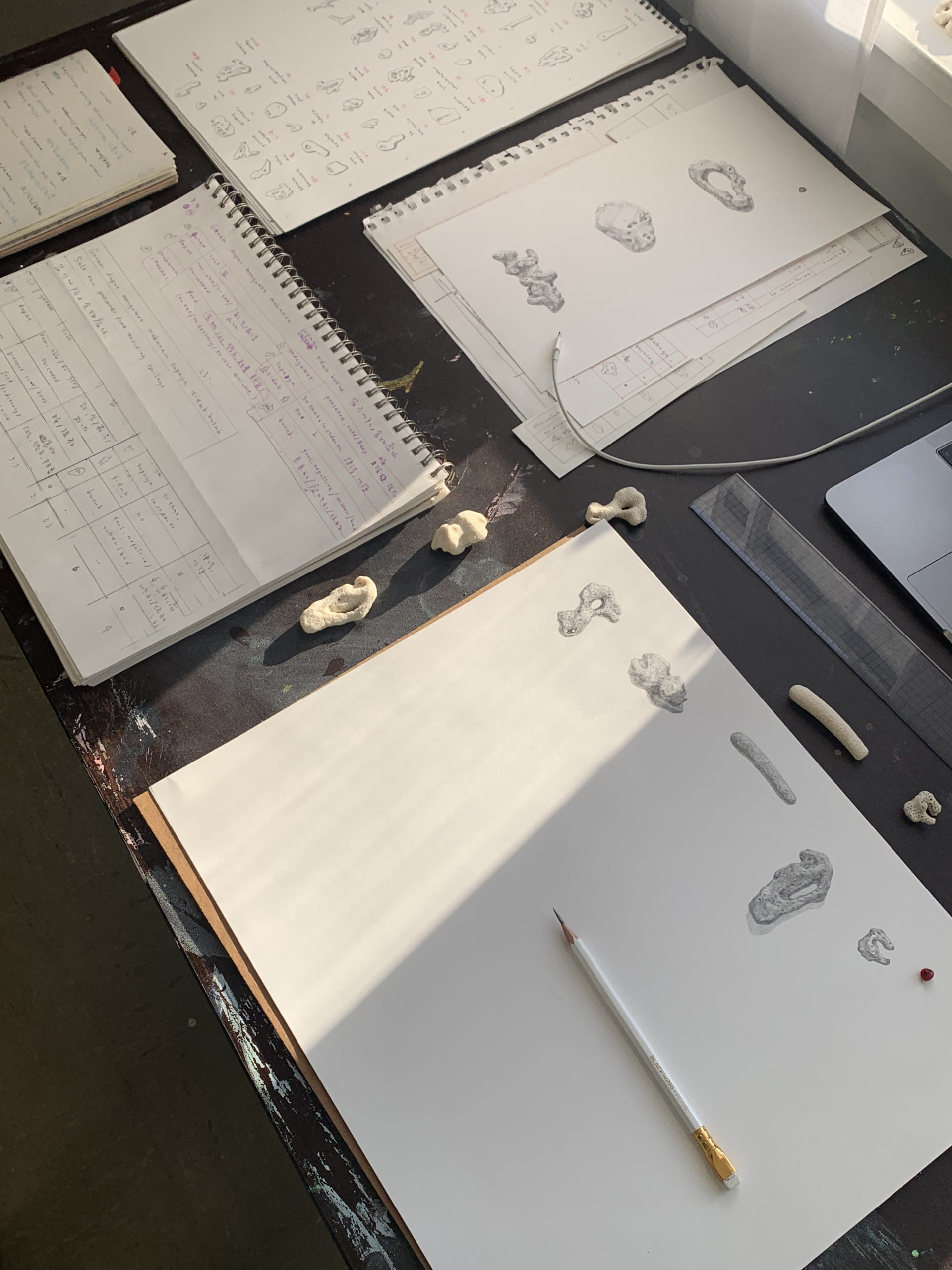

Views of Yuchen’s drawing studio during her time at MASS MoCA in Pittsfield, MA [photo: Chang Yuchen; courtesy of the artist].

Views of Yuchen’s drawing studio during her time at MASS MoCA in Pittsfield, MA [photo: Chang Yuchen; courtesy of the artist]

Views of Yuchen’s drawing studio during her time at MASS MoCA in Pittsfield, MA [photo: Chang Yuchen; courtesy of the artist]

Re’al Christian: So, how’s it going? [laughs]

Chang Yuchen: It’s going—it’s going pretty good. I’m more and more used to it. I feel like I’m [on] military time now. I can hear the bell. The bell was made for the textile and printing factory in [the] late 18th century, and it was not functioning for a while. And then, when MASS MoCA transformed this old factory warehouse into a museum, artists gave the bell, the bell tower, back to life. And it’s now working every 15 minutes. And it’s quite amazing how much we can do in 15 minutes. And it’s also amazing that there are not a lot of 15 minutes in a day.

RC: I’m sure it’s informed the way you work. It’s interesting how time now has to factor into your work. And I feel like, with the quarantine, everyone has become hyperaware of time, and how we spend our time, now that we have such an ample amount of it.

CY: I was talking with a friend a long time ago, [saying] that when you are alone you are faced with your own death. That’s why being alone is so hard, because there is no distraction to block you, you are just staring at your own death directly. And I feel like we are—in one way or another—in that position now, with no distraction, or very little, or none of those normal distractions that we used to have.

I have a studio in New York, and that was my shelter from all distractions. I love staring into my own death. I love being there with my reality. I miss the time, and the light. The studio time is actually not that different. If I am here in this time and space … there’s nothing else truer.

RC: I feel the same way, in terms of working alone and just being alone with my work. I’m very empathetic to my friends who are not used to this new state of self-isolation, but being a writer is already such an isolated task, and I’m sure, being an artist, you can relate to that …. The last time we spoke, we talked about how you didn’t feel like you had the space to really think about art, and how—[technical malfunction]

Re’al Christian interviewing Chang Yuchen [screenshot]

Chang Yuchen interviewed by Re’al Christian [screenshot]

CY: Hello!

RC: Hi, sorry.

CY: Maybe we should do it without video?

RC: Yeah. [both laugh] Okay. Let’s try just doing audio, and hopefully that works.

….

It’s a different way to do an interview, definitely. But this is the world we live in; everyone’s having to adjust. So I was—I was saying that the last time we spoke you talked about not having the space to really make or think about art, and I’m curious about your process and re–establishing that space.

CY: Yes. I think I experienced this event twice. Because I was in China in January, and I came back to New York on February 1st, and I self-quarantined for 14 days.

So, in my self-quarantine days I was just constantly on my phone and switching between social media, Chinese ones, English ones, and Twitter and WeChat. And the thing about China is that there’s no journalism. Even when there is journalism, you have to piece the information [together] and learn some kind of literacy with [it]. But with China, it’s with urgency because everything you are reading or looking at might get deleted, immediately …. And after my self-quarantine, I stepped out to my neighborhood in Bed-Stuy. It’s beautiful. And everyone is enjoying … life in coffee shops and restaurants. I felt so split and disconnected. I went to a coffee shop, and the barista, who’s always very friendly to me, asked, how was my day? I told him I had been looking at news for four hours, and he said, with a very cheerful tone, “Oh, what did you learn?”

I said that I learned that a lot of people are suffering. And he was shocked for a moment, and he said “Oh, that is true.” And I left the coffee shop, thinking that he’s not talking about the same people suffering, but it is true, there are so many people suffering in different forms.

RC: That’s true. I think with the current state of things that trauma is being heightened, and it’s interesting how much transparency people are beginning to have on social media …. People are really opening up about these feelings of loneliness and depression in a time that’s so stressful, knowing that anyone who sees it at this current moment will understand and relate to what they’re going through because the pandemic affects everyone …. It’s affecting people disproportionately, but everyone has a body, everyone has a stake in this.

CY: The fact that we share the same body and how we are related—if you hurt yourself, you hurt people around you, if you protect yourself, you protect people you care about—it’s a very collective-minded way of thinking that we’re not used to, that’s totally against, at least in the US, what people are encouraged to do. And I think that’s why Chinese people are more accustomed to being told to follow orders, willingly or not, but to follow orders, versus in the US, [where] it’s such a mind-shift, it’s such a new attitude that people have to adopt.

RC: Right. Maybe that relates to [the] exhibition Contain, in a way, and your works that were in that show, which I think was put up right after you got back from the protests in Hong Kong.

CY: I actually made those works even before the protest. The masks belong to this project, Use Value, [that] I started in 2016. Should I start at the beginning of Use Value?

RC: Yes, please.

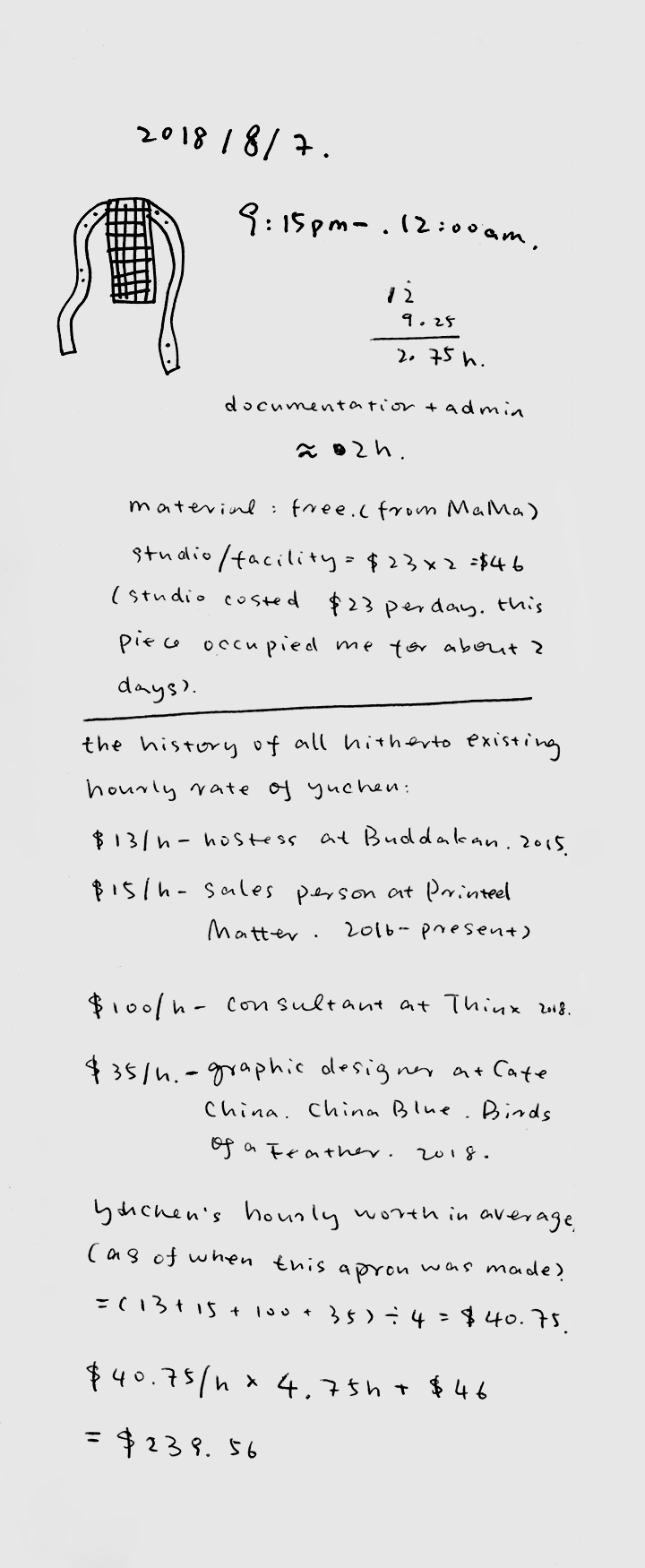

Chang Yuchen, Use Value – Service is intangible by nature, installation view at Bananafish books, Shanghai [courtesy of the artist]

CY: Use Value started in 2016. It was a project in [the] form of commerce. I wanted to make things as commodity to sell, and there were two drives: one was the experience I had working as a hostess, where I was no longer a person but truly a commodity …. I saw my body in two different markets, being valued at two different prices …. I thought my time, my presence was one price and [yet] my feelings, my thinking, was priced in another system. Through Use Value I was trying to draw this two-value system and this two-labor market together …. I would make things, and I would keep a log of how many hours it took me to make. And I would calculate, I would time the hours that I [spent at $13 each], which is the hourly wage that I got from the restaurant, plus cost of the raw material, and that would be the price [at which] I would sell that product. And they are useful commodities …. I think, for me, it’s very important that art exists not only in museums or galleries, but everywhere. In [the] grocery store, in the park, in your closet. I was really intrigued with the idea of making things against categorization or [to] deliberately resist the labor market, and in its essence, the identification of things. The categorization of things.

RC: Right. I like the divide between utility and aesthetic object in these works, specifically in the Use Value pieces …. As you said, they do sort of reject any sort of direct categorization, because they can be worn and they can be used, and many say that art, by definition, is something that is not a utilitarian object.

And then, thinking about them now, especially the masks and how masks have now become such a high commodity and such a rare object, it’s interesting to have these beautiful masks that you made that can’t be used in the same way as a medical mask but still serve this sacred function as an art object.

Chang Yuchen, Use Value – Apron 14 Timesheet [courtesy of the artist]

CY: I guess that’s the cult value and the exhibition value question. Yeah, it’s a great point that we tend to divide utility and beauty …. I remember in an essay called “[The] Loom” that Anni Albers wrote …. Every decision that’s visual has a purpose. Anni Albers wrote [that] it communicates some kind of purity, and that is beauty. Useful things are beautiful in the eyes of Anni Albers.

RC: Right.

CY: I think it’s [a] similar contemplation, categorization. For example, I spent a lot of time doing domestic labor from 2017 to 2018. [And] I was so drawn to my duty; every day [I’d] clean, and I put things in their rightful places … recalling the most ancient action in the past that human beings had to do to take care of each other and to survive, just to live. And I think those acts are so potent and informative to me.

Chang Yuchen, Use Value – Apron 14 (front) [photo: Lane Lang; courtesy of the artist]

Chang Yuchen, Use Value – Apron 14 (back) [photo: Lane Lang; courtesy of the artist]

RC: I like the connection to Anni Albers and thinking about textiles as a craft versus an art, or how it has been historically categorized as a craft as opposed to a fine art, and how textiles have been traditionally associated with women’s work, but also [with] people of color. I think, for that reason, it has been pushed aside in art historical discussions. And I wonder if the fact that textiles are a commodity, if that’s why we’re hesitant to talk about them.

CY: That‘s the danger of [classifications], because they are not neutral. They are someone‘s decision. Someone profited from [these classifications], and they need to be questioned and looked at constantly.

RC: Exactly. Speaking of the divide between the useful and the useless, I know that you‘re working on the coral pieces right now.

CY: Yes, so useless! [laughing]

RC: [laughing] Coral is in this very interesting position, [similar to] language. If you take coral out of its original context, it becomes this useless yet beautiful object. And I was looking at the images you sent me of your studio …. It seems very peaceful and serene, especially in comparison to New York City right now, which is sort of a mess.

CY: I feel almost guilty that I‘m having a great time right now, honestly.

RC: Don‘t feel guilty. You shouldn’t feel guilty!

Chang Yuchen, Coral Dictionary (an alphabet) [courtesy of the artist]

CY: I think this guilt actually relates to your first question, of how I had a difficult time resuming … my practice …. I pretty much stopped watching news because I had a lot of nightmares from the images that I saw. I know I have friends [who] are so strong and keep watching and documenting and spreading information, but I kind of took a break. And I went to my studio again, and I thought that this is what I decided to do with my [life]. And I think I got back to a rhythm of making. When I came to MASS MoCA in March, everyone was very relaxed here; it still felt remote. And the atmosphere just changed the next day. It happened so fast, and all the artists left, and museums closed. Somehow, maybe I had already experienced it once.

I have a writer friend who said to me that she thinks it’s not a moral act to write fiction now, because she was working on fiction …. I really respect that, and I feel that, but I wonder …. I think I am an artist, and I decided to be one because I think I can contribute the most as an artist. I need time, like, to—I am also a citizen, I am also a human being, a daughter, a friend, but I am also an artist. That hasn’t changed. And maybe I can do my part as an artist, as well. I hope.

RC: Yeah. I think that’s a really important takeaway. I think it’s really important to feel useful in the thing you have contributed to society and that you’ve committed your life to.

CY: I really like how we repetitively use the word useful.

RC: Yeah, it’s a re-occurring theme. [laughs]

CY: Because, when I started it, there [were] certain elements of humor in it. Like Use Value, it is apparently …terminology from Marxism, and I was very much influenced by Marx. But using “use value” like almost trying to say to the world, “Use me, please! Use me in the ways that I want to be used. Use me in this way.” These days that I lived very much similar to a monk, and they really made me think maybe [an] artist’s contribution to the world is like a [monk’s]. You think of a monk: they live their own life in isolation, very quietly, but they work very hard everyday to make progress in their own practice. That progress is private, but in the long run, or in the larger scale, it is a contribution to the entire human species, I really believe so. To maintain that distance and to not be productive, to not be profitable, is the contribution of this group of people.

RC: That’s interesting and very relevant as people are forced to stay home, and there’s this sensation that we need to constantly be producing and constantly be working and laboring …. But it’s also important to take those moments of rest, and rest should be embedded in the labor that we do. But it’s not; there’s this stigma against rest that is really coming out now.

CY: Yeah, it’s really interesting how we take … work—to be is to work. To not work is not to be.

Chang Yuchen, Use Value – Masks, installation view at Hesse Flatow during exhibition Contain, curated and documented by Nicole Kaack [courtesy of the artist]

RC: Could you tell me a little bit more about your current project?

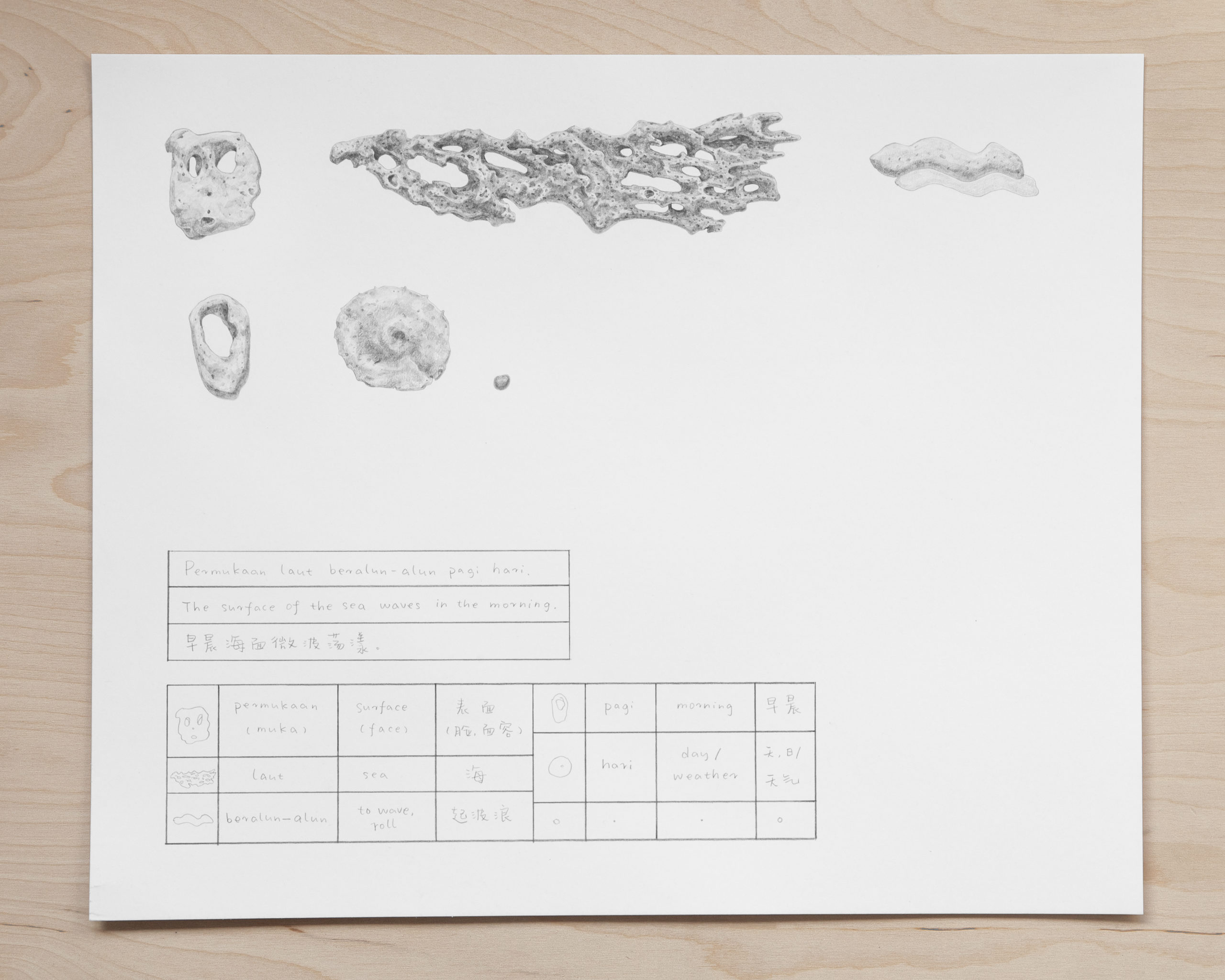

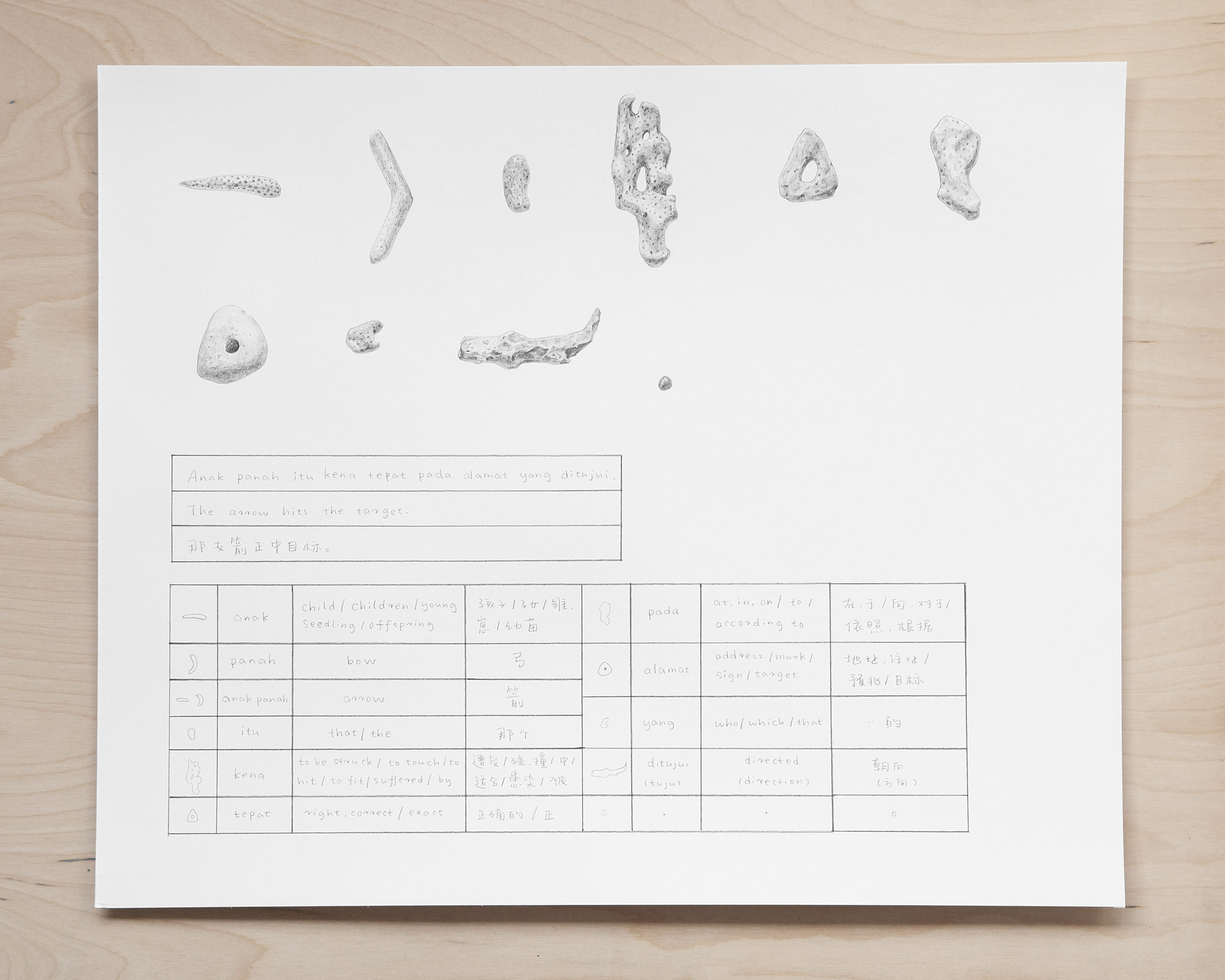

CY: Yes. It’s a language, and it’s funny and bitter and sweet that I’m making language where I have no one to talk to. But it’s also very truthful to the language that I’m making, because I’m the only one who now has a literacy of it. I’m composing a writing system for Bahasa Melayu. It’s a very ancient spoken language that’s part of [the] Austronesia language family. But it never had its own writing system… There was a huge language campaign [in the 1960s], which made the Roman letter Bahasa Melayu, which is called a Rumi [in] the national script, the national writing system. I had a residency in Sabah [Malaysia] last year, last fall. And it was a tiny private island surrounded by corals. And before there were any kind of environmental [notions], fishermen used to home-make dynamite to blow [up] fish under the ocean, so there were a lot of lot of coral bodies’ fragments on the shore …. I collected the corals at first, and naturally I arranged them into rightful orders, into different groups, and they started to resemble an alphabet themselves.

Deeper into the residency I learned from people around me, and also from research, the history, the scar-ridden history of their language. I started to use corals to compose a writing system for Bahasa Melayu. And currently I’m translating some sentences that I found from a dictionary in Malaysia. I think that encountering that dictionary was also very important inspiration for this project, because reading the sentences, the examples in the dictionary, was such an emotional … unexpectantly emotional … thing, because I guess I haven’t been to a tropical area before, and so much of the logic [is] reversed there. Time is different. Like, sunset and sunrise are at six, sharp. We don’t feel time moving, there’s no season …. But they had such a grounded way of presence. At dawn they would just go to pray in private. And I think you and me, we are driven by anxiety, filled by anxiety, [laughing] but Malaysia, everyone [there] is satisfied. Most people seem satisfied with whatever is around them. And I think this reversion of logic made me speechless for two weeks.

Chang Yuchen, Coral Dictionary (The surface of the sea waves in the morning) [courtesy of the artist]

Chang Yuchen, Coral Dictionary (The arrow hits the target) [courtesy of the artist]

CY (cont.): The situation that I encountered was so new to me…. It was a great pleasure to lose language, but when I saw this dictionary, I had another new, great pleasure, [which] was seeing my feelings being articulated. I think that’s how language works. That’s why, in the book Imagined Communities, [Benedict Anderson] thinks the technology of printing was very important for the establishment of national identity. Because when one reads, one will identify with this person’s experience and thinking—“Oh, so we are one kind. This is my kind of people.” And in reading the dictionary, the sentences that talk about the heat. talk about the ocean, talk about the life of the fisherman and of war, of disease …. I think your body is in this completely different physical environment. And of course, your language is, too. And reading those sentences in the dictionary, I think every sentence is like a small novel, encapsulated, and they really taught me how language can be a container full of history for the living experience that’s so unique and specific of this place, of this community.

***

This feature originally appeared in print in ART PAPERS Summer 2020 // Living & Working.

Re’al Christian is a writer and art historian based in New York City. Her writing has appeared in Art in America, Art in Print, BOMB, and The Brooklyn Rail. She is an MA candidate in Art History at Hunter College, and a curatorial fellow at the Hunter College Art Galleries. She earned her bachelor’s degree in Art History and Media Studies at New York University.

Chang Yuchen is an artist based in Brooklyn, New York. She works in an interdisciplinary manner—writing as weaving, drawing as translation, clothing as portable theater, commerce as everyday revolution (see Use Value). By constantly entering and exiting each medium, she strolls against the category of things, the labor division among people.