Ceija Stojka: This Has Happened

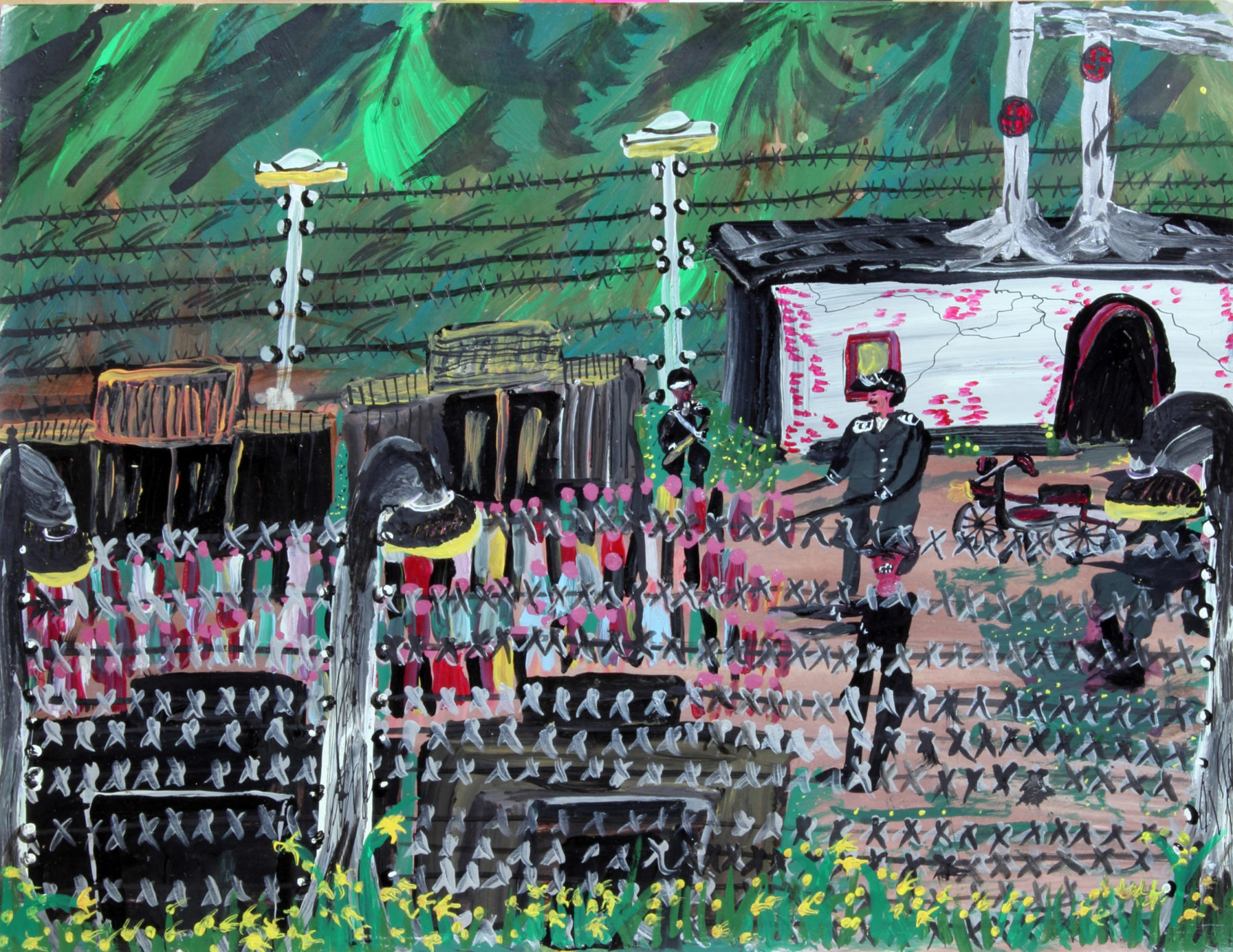

Ceija Stojka, Wo sind unsere Rom? Laaerberg 1938 (Where are our gypsies? Laaerberg 1938), 1995, acrylic, ink, enamel, and sequins on cardboard, 28 x 39 inches [photo: Wein Museum, Vienna]

Share:

When Ceija Stojka was 10 years old, she was captured by Nazi forces and sent to Auschwitz. Fifteen months later she was deported to the Ravensbrück concentration camp, and seven months after that to Bergen-Belsen. By the time she was liberated in April 1945, Stojka had witnessed unfathomable violence, cruelty, and death. She survived the war, but many of her family members—and estimated 73% of her Austrian Romani community—did not.

Anti-Romani sentiment pervaded Europe for centuries before World War II began. After the conflict ended, it still wasn’t safe for survivors to be open about their heritage. Stojka dyed her hair blonde, started a family, sold fabrics and rugs, and tried to regain a normal life.

After decades of silence, Stojka decided to tell her story. In 1988, at age 55, she produced the first of several memoirs with the help of filmmaker and documentarian Karin Berger. Shortly afterward she began a vigorous, self-taught artistic practice. From 1990 to 2012 Stojka created more than 1,000 autobiographical drawings and paintings depicting her life before, during, and after the war. More than 140 of these artworks—along with photographs, books, and a documentary film by Berger about the artist’s life—are featured in Ceija Stojka: This Has Happened at Madrid’s Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía.

Ceija Stojka, Ravensbrück 1944, 1994, acrylic on poster board, 27.5 x 39 inches [photo: Xavier Marchand Collection, Marseilles]

Stojka was born on May 23, 1933, in Kraubath, Austria, to a family of nomadic Romani horse traders. Her paintings show an idyllic childhood filled with close-knit family members, cozy caravans, and blooming landscapes. But the rainbow colors of Stojka’s youth give way to bleaker hues when she depicts the first phase of her trauma: Nazis rounding up Romani and Sinti people throughout the Austrian countryside. In Gefangennahme und Abtransport (Arrest and Deportation) (1995), armed SS forces exit their deportation truck full of prisoners and approach a shrunken family huddled together in fear. As with many of Stojka’s pictures, nature communicates the mood: a jagged, ashen cloud splits the sky, and a barren, desiccated tree foreshadows the calamity to come.

But the most gripping and excruciating scenes depict Stojka’s internment. The artist paints herself and her fellow prisoners as emaciated, faceless stick figures trapped between barbed wire fences, dark barracks, and vicious Nazi guards. Her worst memories are often reduced to a desolate black and white palette, as in Die Angst war groß hinter dem Stacheldrahtzaun im K.Z. Auschwitz (Behind the barbed wire of the Auschwitz concentration camp, there was much fear) (2009). Painted more than 65 years after her ordeal, Stojka’s slashing strokes vividly capture the three key harbingers of horror—guard dogs, barbed wire, and ravens—that appear throughout her visceral pictures of the death camps. Stojka’s work is equal parts harsh and heartfelt. Her scenes are hard to look at, but also hard to look away from.

Ceija Stojka, Die Angst war gross hinter dem Stacheldrahtzaun im K.Z. Auschwitz (Behind the barbed wire of the Auschwitz concentration camp, there was much fear), 2009, gouache on paper, 12 x 16.5 inches [photo: Moritz Pankok Collection, Berlin]

Stojka’s first monographic exhibition in Spain opened just days after the country’s radical right wing Vox party won unprecedented gains in the national general election, making it the third-strongest force in congress.1 Vox has capitalized on fears surrounding the Catalan independence movement, rising Spanish feminism, immigration, and other recent social changes to promote a narrowed, nostalgic vision of Spain that harks back to Francisco Franco’s dictatorship and the Reconquista. Four decades after the nation’s transition to democracy, Vox’s sudden upswell raised urgent questions about Spanish identity, privilege, and history. As the nation grapples with who belongs and who doesn’t, Stojka’s exhibition draws crucial attention to Spain’s own Romani communities.

In his catalog text, Reina Sofía Museum director Manuel Borja-Villel states that that gitanos (gypsies) have historically been excluded from institutional art spaces. But they’ve also been excluded from Spanish society as a whole. Gitanos—a fraught term for Austrian Romani people, and one that still carries a pejorative connotation in certain channels—have lived in Spain for hundreds of years but weren’t granted citizenship until 1978. Today, most of the 750,000 gitanos living in Spain face significant inequalities.2 According to a 2019 study, more than 65% of Spanish gitanos live on 400 euros per month or less, and only 17% of gitana women are formally employed. Fewer than 20% have graduated high school, compared with 80% of the general populace. And whereas just over half of Spanish women have attended college, only 2% of gitana women have.3 Although Stojka’s work depicts another time and place, its focus is the Romani experience, something that should not be completely foreign to Spanish audiences.

Ceija Stojka, This Has Happened, installation view, 2019 [photo: Joaquín Cortés/Román Lores; courtesy of the photographic archive of the Museo Reina Sofía, Madrid]

At the press conference for This Has Happened, curator Paula Aisemberg was visibly moved when she spoke about the unlikeliness of an artist such as Stojka being exhibited in the same museum as Pablo Picasso, whose 1937 painting Guernica hangs on the floor below Stojka’s exhibition. The two artists certainly have their differences in formation and fame, but both left unforgettable testaments to the horrors of war and the dangers of hatred. As the exhibition’s title affirms, Ceija Stojka: This Has Happened is a timely warning amid Spain’s surging nationalism and collective intolerance of the other. Wherever it is seen, Stojka’s poignant work presents a step forward.

Lauren Moya Ford is an artist and writer based in Spain. She has written for Apollo–The International Art Magazine, Art & Object, Artsy, BOMB Magazine, Glasstire, Gulf Coast: A Journal of Literature and Fine Arts, Hyperallergic, Mousse Magazine, Pressing Matters, Sightlines, The Art Newspaper, and Wildflower.

References

| ↑1 | Valdivia, Ana Garcia. “Far-Right Party Vox Becomes The Third Political Force In Spain After Second Election.” Forbes. Forbes Magazine, November 12, 2019. https://www.forbes.com/sites/anagarciavaldivia/2019/11/12/far-right-vox-becomes-the-third-political-force-in-spain-after-second-election/#13d8ee807f85. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | País, El. “La Realidad El Pueblo Gitano, En Cifras.” EL PAÍS. Ediciones EL PAÍS S.L., October 10, 2018. https://elpais.com/cultura/2018/10/10/television/1539170508_189986.html. |

| ↑3 | Europa Press. “Radiografía De La Población Gitana En España: Más Joven, Pero Más Pobre y Con Menos Estudios y Trabajo.” europapress.es. Europa Press, September 28, 2019. https://www.europapress.es/epsocial/igualdad/noticia-radiografia-poblacion-gitana-espana-mas-joven-mas-pobre-menos-estudios-trabajo-20190928120251.html. |