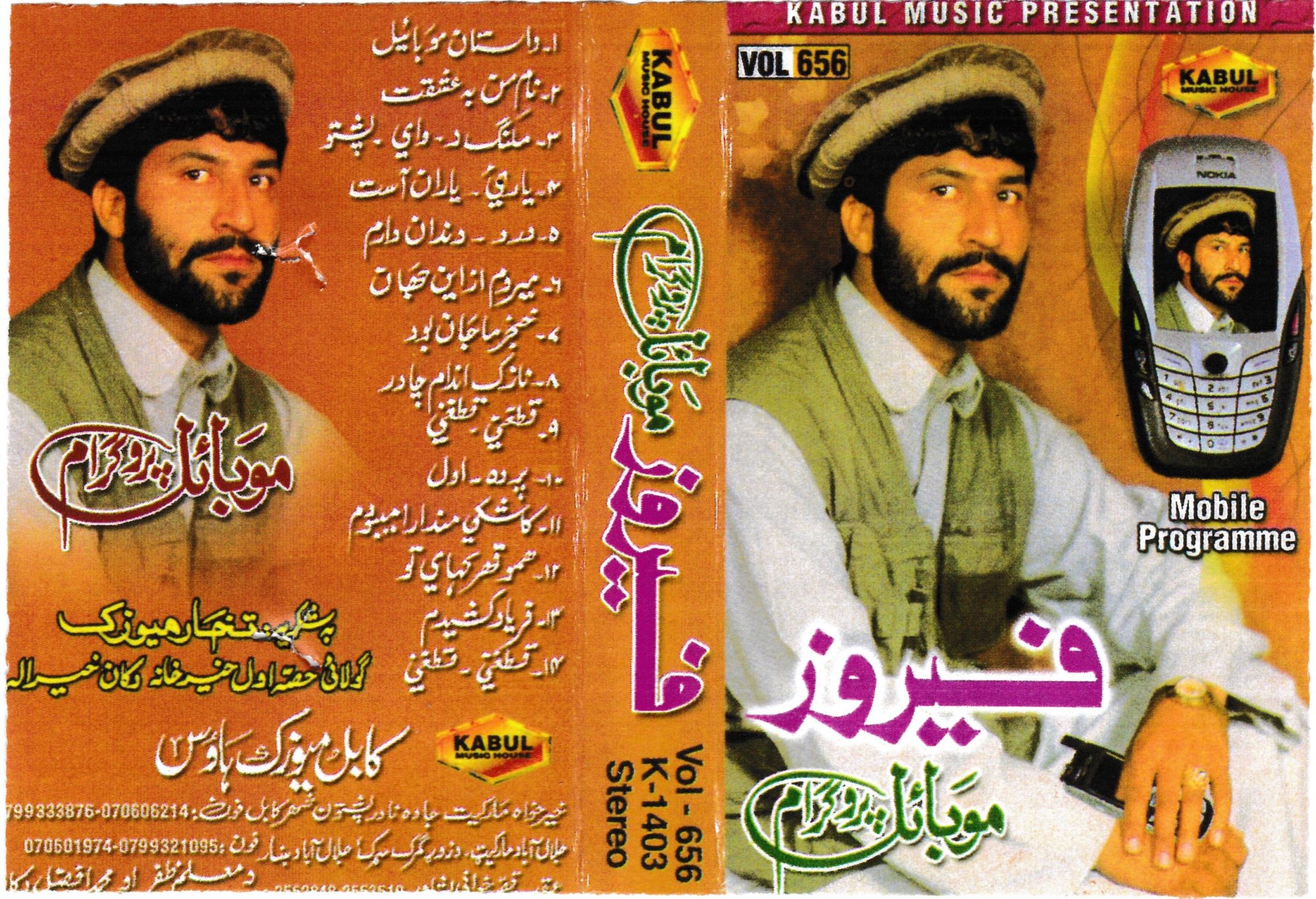

Pakistani Pashto cassette cover: Feroz Kundozi [collection of the author]

Capacious Tapes

At the end of the 20th century, audiocassettes revolutionized both the solitary and social consumption of music. Through personal Walkmans and ghetto blasters, cassettes layered the ambient sounds of everyday life with a diverse backdrop of aural signs.

Share:

Amid an ongoing tendency to excavate the recent past for outmoded objects, artifacts, and forms, and use them to animate cultural groupings—affiliative retro—it is common for many to perceive the audiocassette as the latest piece of media hardware in line for rediscovery. Following the vinyl record renaissance of the previous decade or so, cassettes, we are told, are “back.” Yet the recognized reinsertion of antiquated objects into patterns of usage and production rests on an assumption that these very objects are antiquated and out of use. In many parts of the world, this is not the case. Far from being another passive victim of the onward march of creative destruction that waylaid the MiniDisc, the audiocassette has generated an array of cultural spaces and social forms of consumption—forms paradoxically enabled by the capaciousness of the cassette, but not contained within it. Both in terms of the dimensions and physicality of the cartridge and the spaces its sounds generate, an invitation to inhabit space characterizes the audiocassette, which while atrophying with age and use, even comes to resemble a lived space—say, the built environment of a house or the façade of a store.

Despite their iconic material presence, the social habits and practices that surround the varied uses for which audiocassettes were employed earns them protected status in UNESCO’s Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH). Safeguarding such acts as shadow puppetry, dances, musical traditions, and cuisines, UNESCO’s ICH works to ensure respect for “the practices, representations, expressions, knowledge, skills—as well as the instruments, objects, artefacts and cultural spaces associated therewith—that communities, groups and, in some cases, individuals recognize as part of their cultural heritage.”1

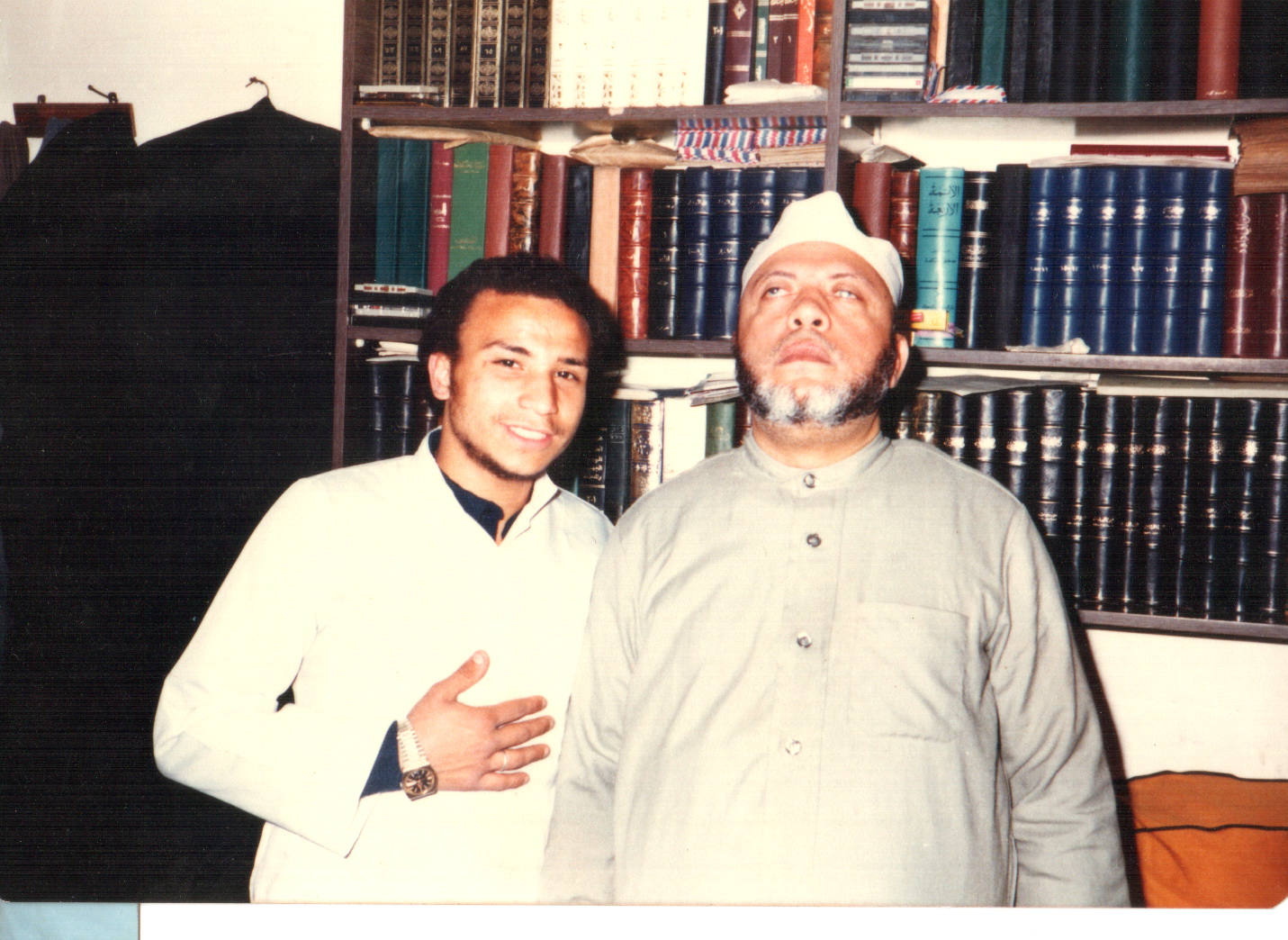

Mohammed El Mehdaoui, Paris, October 2015 [photo: Timothy P.A. Cooper]

Following Fritz Pfleumer’s work with magnetic tape as a form of audio storage, one of the first reel-to-reel recorders arrived with the German-made Magnetophon machine in 1935. The device, free of the cyclic signifier of the record plate, was quickly employed to fool the Allied nations with regard to Hitler’s whereabouts, by broadcasting speeches on the radio purportedly from one city while he was physically in another.2 When small, portable plastic audiocassettes broke into the mainstream in the early 1970s they delivered new agency to the motorist-flâneur—the motorist who will not be beholden to radio programming, for whom the in-car tape deck completed an audiovisual experience defined by movement, synthesis, and choice.

During the Cold War, many saw audiocassettes as a combined symbol of low-cost production, distribution, and duplication. Cheap blank tapes drove the creation of musical undergrounds—particularly in punk and hip-hop—with various hierarchies of consumer value ranging from mixtapes passed around by bands eager to get themselves “out there,” to Grandmaster Flash’s $1-per-minute customized “party tapes.” By the early 1980s there was a recognizable international cassette network, a home taper underground, which recognized that “cassettes are best when used as scratch paper, a reusable medium.”3 This new folk art of home audio duplication and dissemination was closely bound up with emerging mail-art practices and spearheaded by such individuals as Hal McGee, who encouraged the creation of highly personalized and experimental audio art throughout the world, and Conrad Schnitzler, whose Cassette Concerts allowed anyone to perform a variable composition through the near-simultaneous playing of multiple cassettes.4 McGee, like many others, was drawn to the materiality of the audiocassette; it was “inexpensive, portable, and malleable” when compared to the “inflexible and static” nature of the vinyl record, and the “icy digital perfection” of the compact disk.5

Pakistani Pashto cassette cover: Nazia Iqbal [collection of the author]

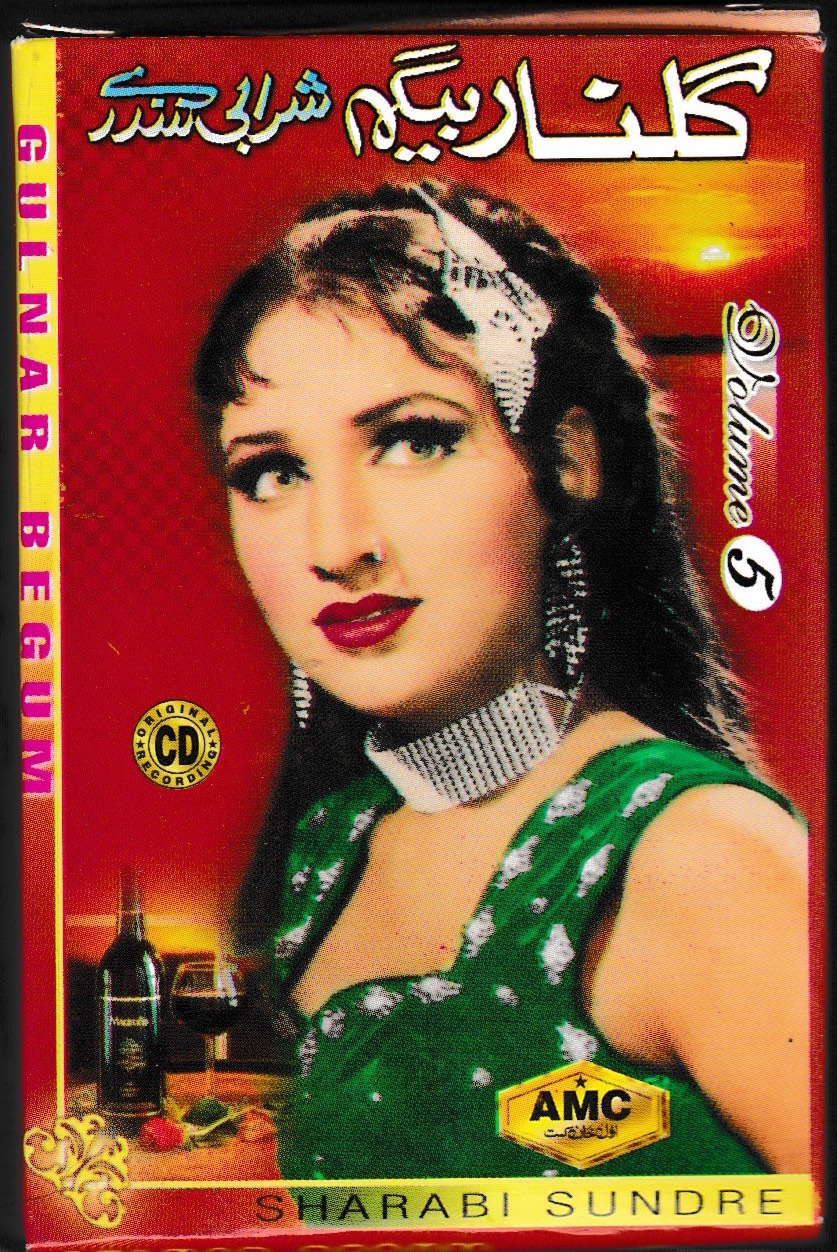

Sharabi Sundre, Gulnar Begum [collection of the author]

Whose Cassette Culture?

Perhaps bolstered by the convenient alliteration, the term “cassette culture” has become a widely used, appropriate way of describing the variety of social practices generated by audiocassette hardware. Yet all too often, a Western narrative—from DIY ethics through Eastern Bloc emancipation and on to the emergence of music piracy—dominates the historical understanding of cassette cultures around the world and overshadows one crucial fact: that cassette use and consumption are alive and well. As of 2009 an estimated 68% of Pakistanis were regularly listening to cassettes, with around half of them buying music of domestic origin.6 We can say that in their nascency, cassettes commonly represented what Peter Manuel called an “emancipatory use of media,” one that was decentralized, and that provided space for signal feedback, retransmission, and collective and self-organized production, in contrast with the one-way transmission of mass media.7 The notion of the living archive as practice—engaging people in social habits that cement into infrastructures, through which culture might be accessed—provides an antidote to the cycle of decline and retro rediscovery that media hardware often undergoes.

Following two decades of war, more than 3 million people fled Afghanistan; many moved across the border to Peshawar in Pakistan, where they began making music as part of the diaspora. From 2002 to 2008 a radical regional government in Peshawar banned music and began ordering police to destroy cassette stores. The result was the dramatic contraction of one of the world’s most compelling and diverse cassette cultures. As with many countries in South Asia, North Africa, and the Middle East, there are powerful memories endemic in Afghanistan of VCRs and cassette players brought back by migrant workers returning from the Persian Gulf. Early Japanese-made hardware was used in Afghanistan throughout the 1970s, allowing small bazaar-based companies to release the work of local musicians and field recordings from weddings or gatherings. Following the pro-Soviet coup and resulting Soviet invasion in 1979, music was brought strictly under state control, and small cassette companies closed in Afghanistan; in refugee camps across the border, music was banned to preserve a state of mourning.8

Yet amid the chaos and infighting between Mujahideen groups that followed the Soviet occupation—during which musicians performed without amplification, and celebratory music was discouraged—a new genre flourished. Fieldwork undertaken by ethnomusicologist John Baily has brought to light a form of cassette—epic that thrived in the period before the Taliban takeover, consisting of extended sung narratives about the exploits of the Mujahideen fighters, punctuated by both simulated and actual bursts of machine-gun fire.9 The civil war was followed by the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan in 1996, when all musical instruments were banned, and sometimes destroyed in public ceremonies, atop vast pyres of plastic.10 More than communal bonfires, these displays were mass executions of the lived social practices of cassette use: “[Taliban] blackened the faces of offenders, tied video cassettes round their necks, and led them through the city on the end of a rope ….”11 ; “they hung television sets from lampposts in mock executions, and ripped the innards out of video and audio cassettes, putting the disemboweled casings on display.”12

Anonymous Mixtape RAKS RX Slim 90 Minute Cassette. Purchased on Rue de la Villette October 2015 [collection the author]

The material remnants of cassette culture exert a powerful, often curious influence on Western conceptions of recent history. A 2015 video game called Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain, set in Afghanistan, features hidden items—”collectables”—scattered across the virtual campaign. Some of these items are cassette tapes—Western ones that can be used to placate enemies or win friends, perhaps symbolizing the archaeological debris of foreign occupation and interference.

The phenomenon of audio and videocassette hardware wresting control of popular culture from those who would happily see it disappear with the tastes of the following generation is certainly not unique to Afghanistan. Across Afghanistan and South Asia, archives are contested spaces wherein the hegemony of linguistic authority is played out, and where regional languages are denied their places in the repository of divided nations. Were it not for video and cassette hardware, fragile vinyl discs and easily degraded material film would have been the final resting places for so many works of moving image and musical art. In India, records were bought in bulk in the mid-1980s largely by cassette pirates who used them as master copies from which they would practice “dubbing” to create a mix of music requested by the buyer.13 Soon institutionalized, this practice led to similar releases of mixes of film, folk, and pop songs understood to be popular locally at the time of production, especially the work of playback singers.14 For many vocalists and musicians, such as Pakistan’s finest Pashto-language film playback singer, Gulnar Begum, it is fair to assume that without the wholesale media migration of the early cassette era, many of her songs—including, in my opinion, the most beautiful three minutes of music yet recorded, Kha Hare Larazghi Azghi She—would not exist in the quality or quantity that they have, particularly with the loss or degradation of the films for which they were originally created. The institutionalization of dubbing—what we might call gray-market mixtapes—also allowed for the curating and compilation of motifs and tenets that make recurrent tropes in musical subject matter more apparent, such as a wonderful cassette called Sharabi Sundre (Drunken Songs) that compiles some of Begum’s film songs.

As tactile and self-contained objects, cassettes can also be understood as both vehicles for meaning and provisional inscriptions, again paradoxically both occupying a vacuum and flexing their capacity to store. Pakistani Pashto-language cassettes often feature watermarks—audio equivalents of the inscriptions that commonly scroll across black-market transfers of Pakistani films and carefully situate the cassette in the commodity chain. A dominant trend in cultural anthropology has been to track the “social life” or the “cultural biography” of objects as they traverse such circuits of consumption.15 For example, through an anonymous mixtape I bought at a flea market in the 20th Arrondissement of Paris it is possible to map some of the personal and the political entanglements of North African communities in Paris during the early 1990s. Recorded onto a Turkish-made blank RAKS RX Slim 90 Minute cassette tape manufactured between 1993 and 1995, when the violence of the Algerian Civil War was at its height, we find Chaoui music from the Aurès Mountains, Sétifi music from the eponymous city in northeastern Algeria, and the amplification of Pop-Rai—a combination that evidences the powerful presence of Algerian diasporas in France, and the ways music was experienced by North Africans in France while many such styles were outlawed in Algeria.16 A short distance from the street where I acquired this lovingly compiled and labeled micro-archive stands what seems to be one of Western Europe’s last remaining cassette stores, run by the affable Mohammed El Mehdaoui, who responded to my request for a copy of Oum Kalsoum’s Siret El Hob with his own, pitch-perfect, live-crooned rendition. Within North Africa itself, the mobility of cassette recordings of singers heightened the visibility of cultural groups usually marginalized by state culture. In Egypt the success of Ali Hemida’s Lolaaky brought the Bedouin of the Western Desert from the margins of society to the forefront of popular musical taste.

Cassette store Peshawar [photo: Majeed Babar]

The Ambient Spaces of Cassette Consumption

It is clear that cassette cultures at the end of the 20th century imparted much of the aural soundscape of everyday life. Less acknowledged are the ways that cassettes began to form a transcultural infrastructure for personal communication, brought about seismic shifts in access to written materials such as religious texts, and offered secure spaces to minority groups for creating a sense of autonomy and self-determination. Long before hardware for the recording of sound arrived, the singing of devotional poetry and scripture was key to the soundscape of religious life across the Islamic world. Cheap to produce, copy, and disseminate, cassette-sermons by small-time preachers could reach immense audiences—suddenly the Egyptian Sheikh Kishk, blind from childhood, could be heard wherever Arabic-speaking communities were to be found, as his cassette-sermons, suppressed by authoritarian regimes in the Middle East during the 1970s, circulated widely by hand throughout the region. Whereas today the clandestine transfer of religious sermons is associated with militancy, when cassette-sermons first appeared their radical address was rarely toward violence, and instead toward auto-didacticism. Their listeners were the illiterate, those without access to education or the time to study the scriptures, or those unsure of the rules relevant to their particular community. In short, the cassette-sermon contributed to the brokering of the Islamic Revival, in its myriad forms, and manufactured its success through its address to counterpublics.17

Access to audio hardware and the societal impact of literacy were closely connected elsewhere. In Indonesia, audiocassettes were often used as capacious vehicles for centuries-old traditions of oral storytelling and oratory. As rites of passage into modernity and as audio handbooks on the ways ritual cultures and forms of kinship should be practiced and maintained, Indonesian cassette-dramas by ethnic Batak theatrical ensembles in the Sumatra region exemplify how cassettes contributed to reanimating kinship traditions. As an example of what happens when a culture with primarily oral traditions reappraises and adapts its forms of cultural expression to new mass media technology, Batak cassette-dramas also offered the potential listener the choice to opt out of what we have called an “intangible” cultural practice: to simply turn the cassette off or not purchase it altogether.18

The arrival and availability of audiocassette technology was correlative with new opportunities for global mobility, either through economic or forced migration; logically, cassettes were used as audio letters sent home from abroad by laborers or people displaced by war. For those who sent tapes from their labor pilgrimages in the oil-rich Gulf, the hardware that these cassette letters were played upon back home was often initially bought in the Gulf States, where Japanese media technology was widely available, making the initial hardware gift generative of a kind of cross-border contact. Unlike a telephone call, an audio letter could be played and replayed to a group—a surrogate for the physical form of the absent relative. With the authority of the delivered or promised wealth earned abroad, the audio letter’s sender might also issue edicts on how the money sent home should be spent. In Amitav Ghosh’s ethnographic novel In an Antique Land (1993), the author recalls listening to an audio letter sent from Iraq to an Egyptian family who “listened to him rapt, all the way to the final farewells, though they have clearly heard the tape through several times before.”19 Inevitably, ambient sounds and background noise seep through these recordings, capturing a sense of proximity and simultaneity, and a presence that collapsed the distance between the assembled family and their kin laboring abroad.

Sheikh Abdelhamid Kishk [via assabile.com]

Ethnomusicologist Angela Impey begins her remarkable study of the South Sudanese Dinka people’s audio letters by recounting being played a family audio letter, sung by an associate’s uncle some two decades earlier: the words of the seemingly innocuous recitation were in fact furious imprecations of the sender’s unfaithful wife, which the man recorded, copied, and sent to relatives to give them the news of the rupture in his marriage. Dinka audio letters were not always intended for those who eventually received them—some family members felt that extended family should listen to the message, copied the cassette, and passed it on to distant relatives in the diaspora. As these practices earned a reputation for being able to collapse distance and materialize human relationships, the audiocassette thus became the carrier of a kind of choice—even after the availability of digital media.20

Capacious media is defined by the personal choice of the user—economic choices, for instance, such as those regarding how he or she will ration the capacity of the storage unit. Capacious media is a material infrastructure, visible, accessible, and indeed capable of providing storage for media, and of functioning as a vehicle for its mobility through cultures and contexts. Cassette copying created an infrastructure of spontaneous archives as living practices, some of the results of which included music and film piracy. Other results are even more difficult to discern. As material entities and technological objects, informal media infrastructures are vulnerable to atrophy and deterioration; like any archive, they require tactics of preservation, salvage, or excavation. While hegemonic electronics manufacturers deal in planned obsolescence—the policy of designing a product with a forecast usage period, after which it will become obsolete, requiring new purchases—consumers around the world have forged the inevitability of breakdown into what anthropologist Brian Larkin terms “repair as a cultural mode of existence.”21 Still, when the resurgence of cassettes is remarked upon, it is usually viewed through the prism of an antique object returning to circulation through the fetishes of a small group of marginal consumers. Whichever form it takes, consumption is an active way of relating to and inhabiting social and global cultural systems. Collecting objects and reinserting them into chains of reception that differ greatly from those on which they were originally exchanged reveals how objects can become independent systems.

Pakistani Pashto cassette cover: Feroz Kundozi [collection of the author]

The Living Archive

Anticipating his eventual martyrdom, Osama bin Laden used his own archive of audiocassettes to self-mythologize the movement that revolved around his own persona. Fifteen hundred tapes were discovered when Bin Laden’s regional al-Qaeda headquarters in the city of Kandahar was evacuated. The collection has since been studied by US academic Flagg Miller, who found in these objects a diverse set of aural scraps at once insular and profoundly public, like a manifested form of the cellular hive mind of the modern terrorist network.22 Flagg found that the CIA misrepresented the extent to which al-Qaeda was concerned with the West. The vast majority of Bin Laden’s cassette archive—besides extended poetry recitals—consisted mostly of diatribes against other Muslim sects and leaders. Recently the British Library refused to house a similar trove, in this case a variety of digitized documents known as the Taliban Sources Project, relating to the Afghan Taliban, in apprehension of British anti-terrorism laws. Having been laboriously translated from Pashto into English, the archive would have been an unmatched resource for both anti-terrorism scholars and those studying the recent history of Afghanistan. As with Bin Laden’s cassette collection, much of the Taliban Sources Project would have been audio-files of cassette tapes: the informal infrastructure of the clandestine, cross-border world of global terrorism.

For good or ill, cassettes signaled a watershed in the vast topography of modernity, whereby things began to be preserved through transmission, copying, and dissemination. They should not be mourned, salvaged, or granted a regional rebirth. Rather, the practices that surround these media forms, including the remarkable story of cassette use, should be recognized as a common, if greatly diversified, infrastructure—a form of intangible cultural heritage that is as much a social activity as it is a material object.

Timothy P.A. Cooper is an independent programmer, journalist, and researcher whose work is grounded in both anthropology and media history. His writings explore pirated media, its artistic capital, and informal infrastructure, as well as modern visual hierarchies of both aesthetic and anthropological value.

References

| ↑1 | Article 2:1, Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage, UNESCO Convention, 2003. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Barry Fox, “The real history of tape recording,” New Scientist (February 9, 1984), 45. |

| ↑3 | Robin James, Cassette Mythos, ed. Robin James, Autonomedia, 1992, www.archive.is/UzP1R |

| ↑4 | Gen Ken Montgomery, “Conrad Schnitzler’s Cassette Concerts,” Cassette Mythos, ed. Robin James, Autonomedia, 1992, www.archive.is/r1EAY#selection-199.1-214.0 |

| ↑5 | Hal McGee, “Homemade experimental music,” Cassette Mythos, ed. Robin James, Autonomedia, 1992, www.archive.is/UzP1R |

| ↑6 | This Gilani poll was conducted in Pakistan by Gallup Pakistan, affiliated with Gallup International Association, among a sample of 2,562 men and women from rural and urban areas of all four provinces of the country, during October 2008. |

| ↑7 | Peter Manuel, Cassette Culture: Popular Music and Technology in North India (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993), 4. |

| ↑8 | John Baily, “Can you stop the birds singing?”—The censorship of music in Afghanistan (Copenhagen: Freemuse, April 2001), 7. |

| ↑9 | Baily, 30. |

| ↑10 | Timothy Cooper, “Destruction Ceremonies as 21st Century Book Burning,” Rhizome, June 2014, www.rhizome.org/editorial/2014/jun/19/pyres-profane-and-profound-when-destruction-cultur |

| ↑11 | From The Sunday Times, March 24, 1996, referenced in Baily, 36. |

| ↑12 | From The Guardian, October 10, 1998, referenced in Baily, 37. |

| ↑13 | Manuel, 81. By 1986 pirated cassettes accounted for 95% of those sold in India. |

| ↑14 | Playback singers provide prerecorded vocals, which are lip-synced on film by the leading actors. |

| ↑15 | The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective, ed. A. Appadurai (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1986). |

| ↑16 | Joan Gross, David McMurray, and Ted Swedenburg, “Arab Noise and Ramadan Nights: Rai, Rap, and Franco-Maghrebi Identities,” Diaspora: A Journal of Transnational Studies 3, no. 1, Spring 1994. |

| ↑17 | Charles Hirschkind, The Ethical Soundscape: Cassette Sermons and Islamic Counterpublics (Columbia University Press, 2006). |

| ↑18 | Susan Rodgers, “Batak Tape Cassette Kinship: Constructing Kinship Through the Indonesian National Mass Media,” American Ethnologist 13, no. 1 (February 1986): 39. |

| ↑19 | Amitav Ghosh, In an Antique Land (London: Granta Books, 1994), 323. |

| ↑20 | Angela Impey, “Keeping in Touch via Cassette: Tracing Dinka Songs from Cattle Camp to Transnational Audio-letter,” Journal of African Cultural Studies (2013): 10. |

| ↑21 | Brian Larkin, Signal and Noise: Media, Infrastructure, and Urban Culture in Nigeria (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2008), 235. |

| ↑22 | Flagg Miller, The Audacious Ascetic: What the Bin Laden Tapes Reveal About Al-Qa’ida (London: Hurst & Company, 2015). |