Bleeding Out: On the Use of Blood in Contemporary Art

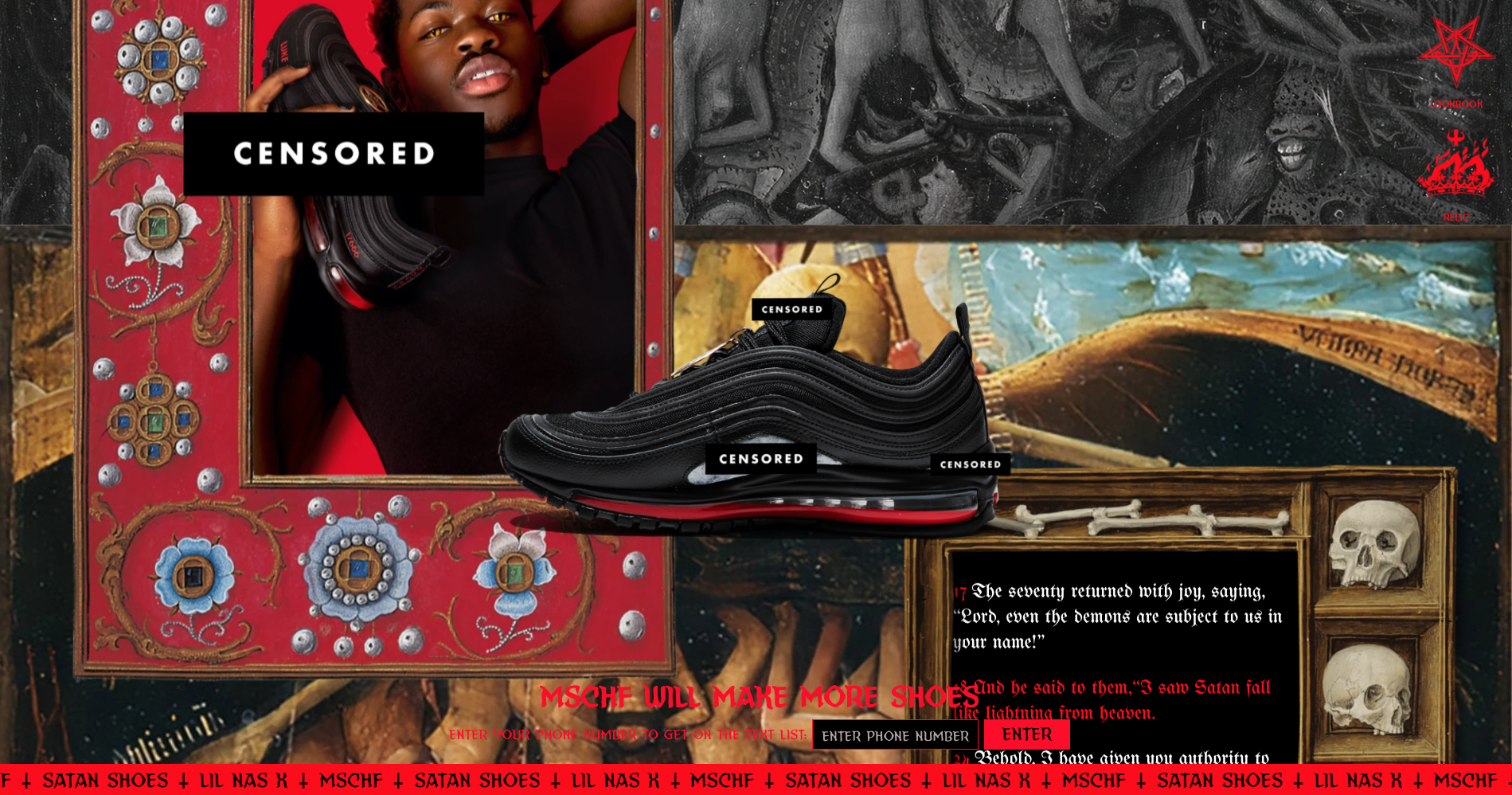

Satan Shoes, 2021 [photo: Screenshot courtesy of MSCHF]

Share:

In March 2021, musician Lil Nas X released 666 pairs of “Satan Shoes.” The red and black Nike Air Max 97s were fastened with bronze pentagrams and embroidered with citations from the Gospel of Luke. A drop of human blood was placed in each sole. MSCHF, the Brooklyn-based artist collective that collaborated with Nas on the kicks, defended their product amid the controversy of its release. In reference to the use of MSCHF members’ own blood, a spokesperson for the group said, “We love to sacrifice for our art.”

Nike sued MSCHF for trademark infringement, and the companies have since settled. Meanwhile, Nas faced the disdain of conservatives and religious leaders, who decried the musician for “devil worshipping.” Nas responded to his critics with a YouTube video, “Lil Nas X Apologizes for Satan Shoe,” which, despite the promise of its title, consists of a clip from his “MONTERO (Call Me By Your Name)” music video, in which Nas—clad in boxer briefs, thigh-high boots, and chains—gives the devil an impressive lap dance.

Lil Nas X with Satan Shoes, 2021 [photo: Screenshot courtesy of MSCHF]

In “Old Town Road” (2019), Nas’ entrance into the country music genre, the singer (who is Black and openly gay) disrupts traditional notions of what a country star should be, threatening the conventions of a genre maintained by a gate-keeping, White, God-fearing establishment. Throughout the “MONTERO” music video, Nas confronts his audience with traditionally sacrilegious imagery, including glorified depictions of hell, murder, and a sexual encounter with the serpent in the Garden of Eden. The CGI-rendered kingdom of Montero provides an anarchic space wherein Nas can dance with the devil, freely expressing and celebrating taboo qualities and inclinations. The presence of blood in the Satan Shoes insinuates equally transgressive qualities, but also instills in the wearer a sense of intimacy with Nas and his creative team—a sartorial blood pact between misfits. Nas reminds fans of their shared humanity by proving that he too bleeds.

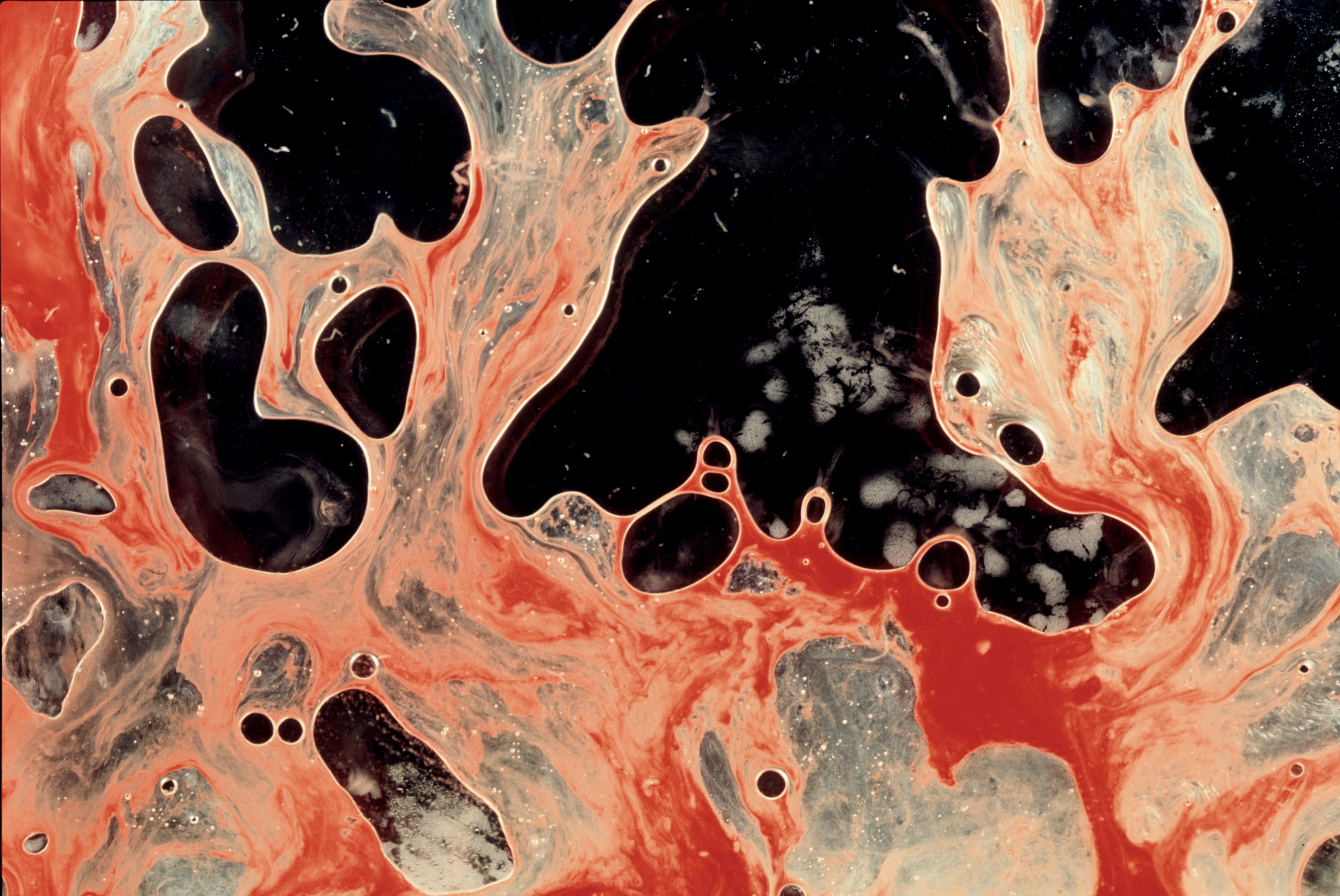

In the late 1980s and early ’90s, Andres Serrano’s photographic work inflamed conservatives due to the artist’s use of urine, blood, semen, and milk to explore themes of sexuality and religion. In Immersion (Piss Christ) (1987), Serrano depicts a crucifix submerged in a glass of his own urine. Blood and Semen V (1990), produced at the height of the AIDS crisis, reduces the life/death cycle to a mixture of two bodily fluids, as if seen under a microscope. Through this abstract composition, Serrano forged a self-referential aesthetic that repurposes the body and its fluids as available artist material.

Andres Serrano, Semen and Blood III, 1990 [photo: courtesy of Andres Serrano and Nathalie Obadia gallery]

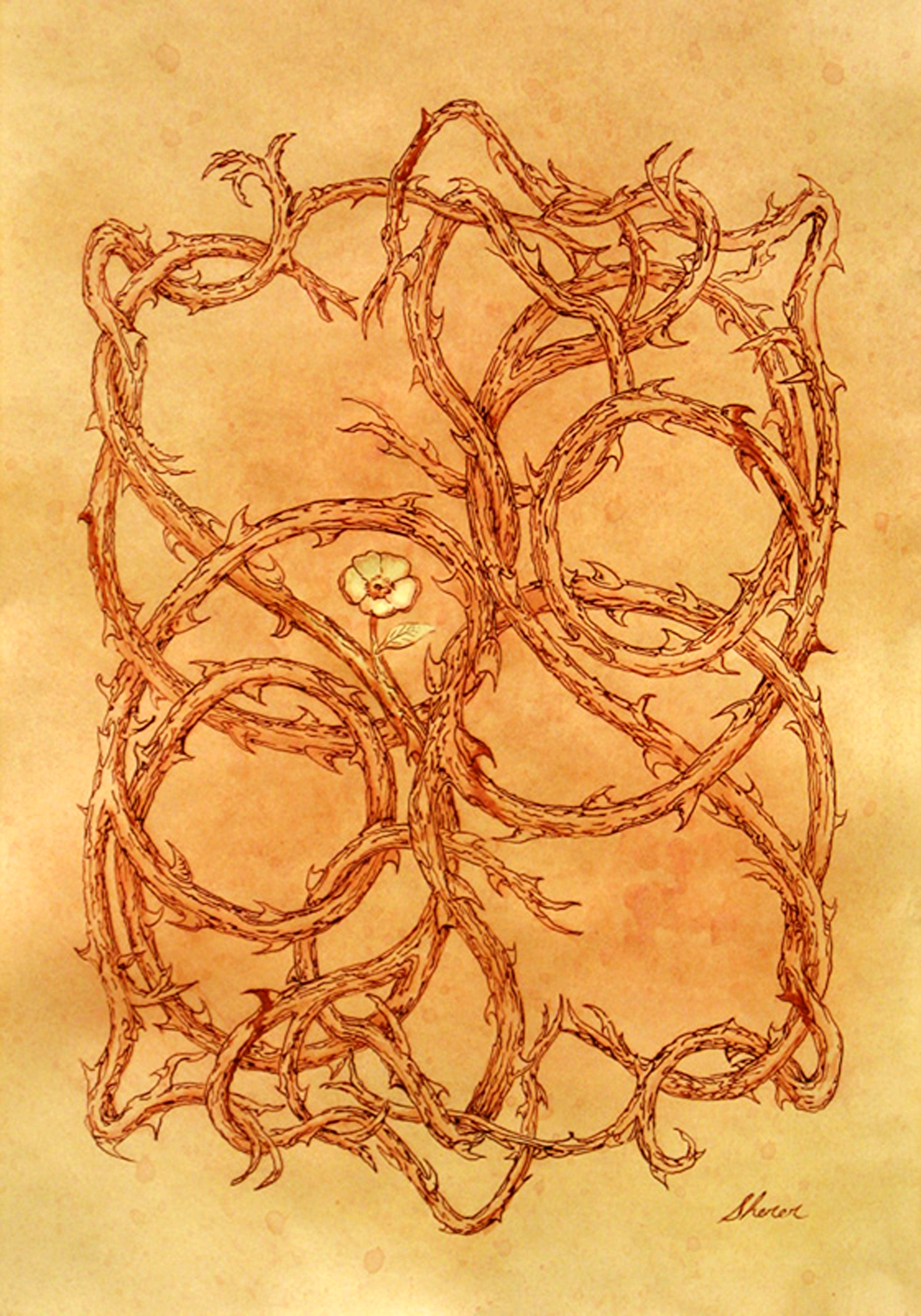

Elsewhere, Robert Sherer mixes his HIV-negative blood with that of an HIV-positive friend in Blood Works (1997–present), a series of Victorian-inspired, still-life drawings of flowers and memento mori. Sherer chose blood as his medium to examine homophobia and attitudes toward HIV/AIDS, resting on the visually imperceptible distinction between HIV-positive and -negative blood. Artist Ron Athey stirred controversy in 1994 when he was accused of exposing his audience to HIV during a performance that involved bloodletting, Four Scenes In a Harsh Life, at the Walker Art Center. But the event was erroneously reported; Athey cut the back of his friend Divinity Fudge, who was HIV-negative, and absorbed the blood on paper towels that were then suspended over the audience. Athey, who has been HIV-positive since the mid-1980s, also uses his own body as a medium, inflicting pain and engaging with fetishism to explore themes of religion, sexuality, and suicide. In Incorruptible Flesh, Athey’s ongoing performance series begun in 1996, the artist grapples with his mortality by enduring abject physical pain: having hooks attached to his eyelids, saline injected into his scrotum, and a baseball bat inserted into his anus.

The work of Serrano, Sherer, and Athey was contested during the “culture wars” of the 1990s, which were primarily battles over public funding for the arts that pitted conservative politicians against provocative artists. The sensationalism of Athey’s performances has all too often gained more attention than the integrity of the work: Athey sacrifices his body, plunging into the darkest depths of human desire and fear in an act of catharsis for himself and the viewer. Athey’s bloodletting is activism, suggesting that no feeling is too radical to produce an image.

Robert Sherer, Stronghold, HIV- blood, paper, 26 x 20 inches [ photo: collection of Steve Smith, courtesy of the artist]

Artists have also grappled with blood’s stigma through representations of menstruation. Christian associations of shame with menstrual blood have deep Biblical roots: the book of Genesis describes how Eve was punished for immorality with the curse of monthly menstruation and painful childbirth. A more modern explanation for this stigmatization from feminist writer Luce Irigaray concludes that a woman’s “leaky body” has been thought to possess a lack of control, the subject of contempt by men, who inhabit a superior “sealed body.”

Second-wave feminism inspired women artists to use the female body, often their own bodies, to express their suffering and interrogate gender roles and visibility. In 1973, Judy Clark began collecting menstrual blood, which she placed on slides arranged in a grid. The work, Menstruation, was exhibited along with other substances Clark collected, such as nail clippings, hair, and urine. The piece indirectly offers an antidote to the dynamic Irigaray describes, displaying the products of a “leaky body” through an organized, controlled medium. Clark revises gendered blood to resemble something that might appear in a scientific lab, like a DNA sample. This taxonomical approach renders the subject matter as controllable—perhaps, applying Irigaray’s logic, it makes the subject matter more palatable to viewers. On the other hand, a comparison could be made between Clark’s clinical presentation and the images associated with oppressive systems, such as sterility and eugenics, possibly undermining the revolutionary quality of the work. Judy Chicago’s Red Flag (1971) depicts a woman in the act of removing a bloody tampon. The work bridges abstraction and documentary, the vacant space between two legs is interrupted by fingers pulling on a red string. With Red Flag, Chicago has said, she intended to “introduce a new level of permission for women artists.” Both Chicago and Clark’s formal presentations of their respective works, through material and format, elevate the image of menstrual blood—and, by association, women’s experience—as worthy of artistic and intellectual exploration.

In 1982, Ana Mendieta dragged her hands, soaked in animal blood and tempera paint, down a white piece of paper to produce an image resembling her own silhouette. Body Tracks, a performance at Franklin Furnace in New York, produced a series of such works on paper. Previously, Mendieta produced the Silueta series (1973–1980), “earth-body sculptures” that symbolically teetered between presence and absence. Many of the works in the series were created outdoors, in situ, using ephemeral materials such as fire or sand. Mendieta preserves her corporal form through mimesis, prompting the audience to reconcile the gap between reality and representation as they’re faced with a shape that documents the artist’s former presence.

Tameka Norris, Untitled | RADICAL PRESENCE | YBCA, 2015 [photo: screenshot courtesy of Youtube and Yerba Buena Center for Visual Arts]

Tameka Norris’ Untitled (2012–2015) operates in a similar manner to Mendieta’s siluetas. In her performance, Norris cut her tongue with a knife before moving her mouth along the gallery walls, leaving behind long trails of blood and saliva. Norris’ “minimalist landscape” addresses the absence of Black bodies in the history of painting. She confronts the white cube with a record of pain, using her body as a tool to render Black suffering, validating an experience that is often omitted or dismissed.

Blood corrupts conventions of purity and privacy to suggest all elements of the body can be used for expression. In Yoko Ono’s Blood Piece (1960), included in her conceptual art book Grapefruit (1964), she writes, “Use your blood to paint. Keep painting until you faint (a.). Keep painting until you die (b.).” Perhaps what’s most disturbing about the medium is not its visceral quality but instead its conceptual underpinnings: blood captures the pervasive anxiety among artists to endure through their work even after they’re gone. This anxiety is often concealed behind the strength of viewers’ personal, negative responses of repulsion, horror, or offense. Looking at a bloodwork sends the viewer inward to reflect upon their own uneasiness with mortality. In this way, our discomfort is not with the artist or the work—but with ourselves.

Lydia Horne is a writer, teacher, and artist living in Los Angeles. She is currently pursuing her MFA in Photography at California Institute of the Arts, where she produces multimedia work using surveillance video, fabric, film, and cake. Lydia mentors students of all ages to strengthen their creative and academic writing through programs at Los Angeles Public Library, Problem Library, and 826 Valencia. Lydia formerly worked at WIRED in San Francisco.