Bioshelter Toilet

Share:

With the conviction that the world’s ecosystems were under siege, fisheries biologists John Todd and William McLarney, with writer Nancy Jack Todd, developed a grand experiment to create a biologically and socially sustainable community. From their discussions arose the New Alchemy Institute (NAI), an organization intended to “restore the lands, protect the seas, and inform the Earth’s stewards” through the development of small, simple, and sustainable technologies.

According to John Todd, Swedish Clivus Multrum dry toilets were “technologically simple … despite their biological complexity,” making them well-suited for the institute’s mission at the Prince Edward Island Ark (1976)1. Indeed, this statement is a fitting way to describe many of the solutions the New Alchemists implemented both on the large scale (in the self-sufficient, sustainable, fully integrated Canadian bioshelter) and on the small (in myriad agricultural, aquacultural, and energy production experiments they attempted at their Cape Cod farm, beginning in the early 1970s).

The New Alchemy Institute, interior of Cape Cod Ark during winter [courtesy of The Green Center / The New Alchemy Institute]

From John Todd’s perspective, alchemy—the ancient metallurgical discipline by which practitioners theoretically transformed base metals into gold through physical and spiritual processes—was a fitting analogy for the work he and his partners would soon undertake. The New Alchemists believed that a restoration of environmental well-being required comprehensive, fundamental changes in the current societal structure. They also believed that their small-scale experiments in alternative energy production, organic agriculture, aquaculture, and self-sufficient building were alchemical phases in an ultimate global transmutation. Like their predecessors, the “Alkies” depended, methodologically, upon the concept of the microcosm. The microcosm signified the macrocosm; the elemental, human, and divine held the same essential matter.2 This conception of the world appeared in the scientific work of alchemists, both bygone and “new.” Traditional alchemists depended upon a Hermetic vase, or aludel, in their esoteric acts of sublimation, to create a microcosmic space meant to reflect the transformative properties of the natural world. Correspondingly, the New Alchemists built semi-closed ecosystems, called Arks, to divine a healthier, more verdant future.

When examining the group’s work, from its impressive bioshelters to its small-scale agricultural experiments, the NAI’s compost projects are perhaps the most transparent applications of “new alchemy.” Similar to traditional alchemical practice, in which common metals were transformed into gold, this “new” alchemy converted local waste matter into nutrient-rich topsoil, a different sort of precious substance. Perhaps more distinctly than other New Alchemy ventures, this product, a variegated embodiment of the surrounding ecosystem, represented the institute’s sensitivity to its immediate environment, as well as the experimental symbiosis that permeated its operations.

New Alchemy’s first major composting initiative began in 1974, when Tyrone Cashman and Susan Ervin began testing a 14-day method, first developed at the University of California.3 In accordance with the study, Ervin and Cashman employed such materials as manure, leaves, and grass clippings culled from local horse stables and the county dump. They also adapted the California scheme to the East Coast farm landscape by supplementing the detritus with weeds from the NAI gardens; dinner scraps of the tilapia cultured in McLarney’s fish pools; and local menhaden, a fertilization method borrowed from the Cape’s former Wampanoag tribes, which purportedly planted a menhaden beneath each corn seedling to support growth.4 As the scope of the NAI’s work grew from experimental agriculture to self-sustaining enclosed ecosystems, however, members looked for ways to incorporate additional waste materials into their compost.

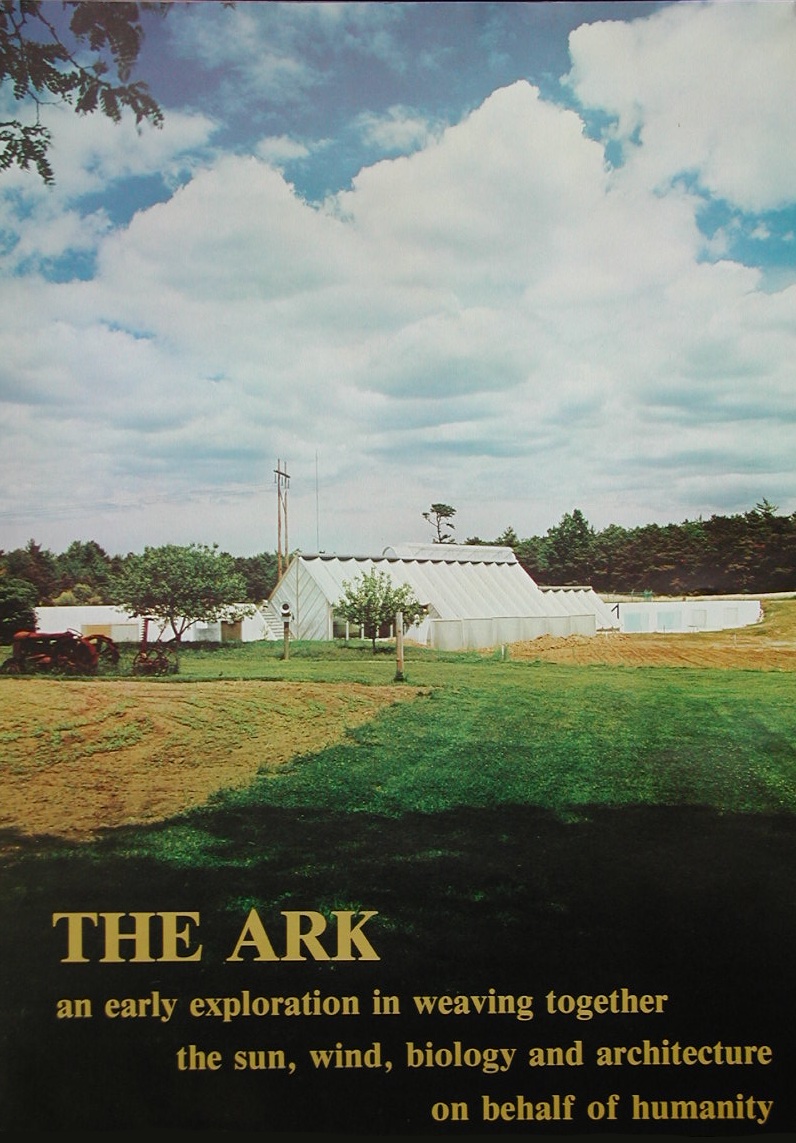

The New Alchemy Institute, Cape Cod Ark poster, 1976 [courtesy of The Green Center / The New Alchemy Institute]

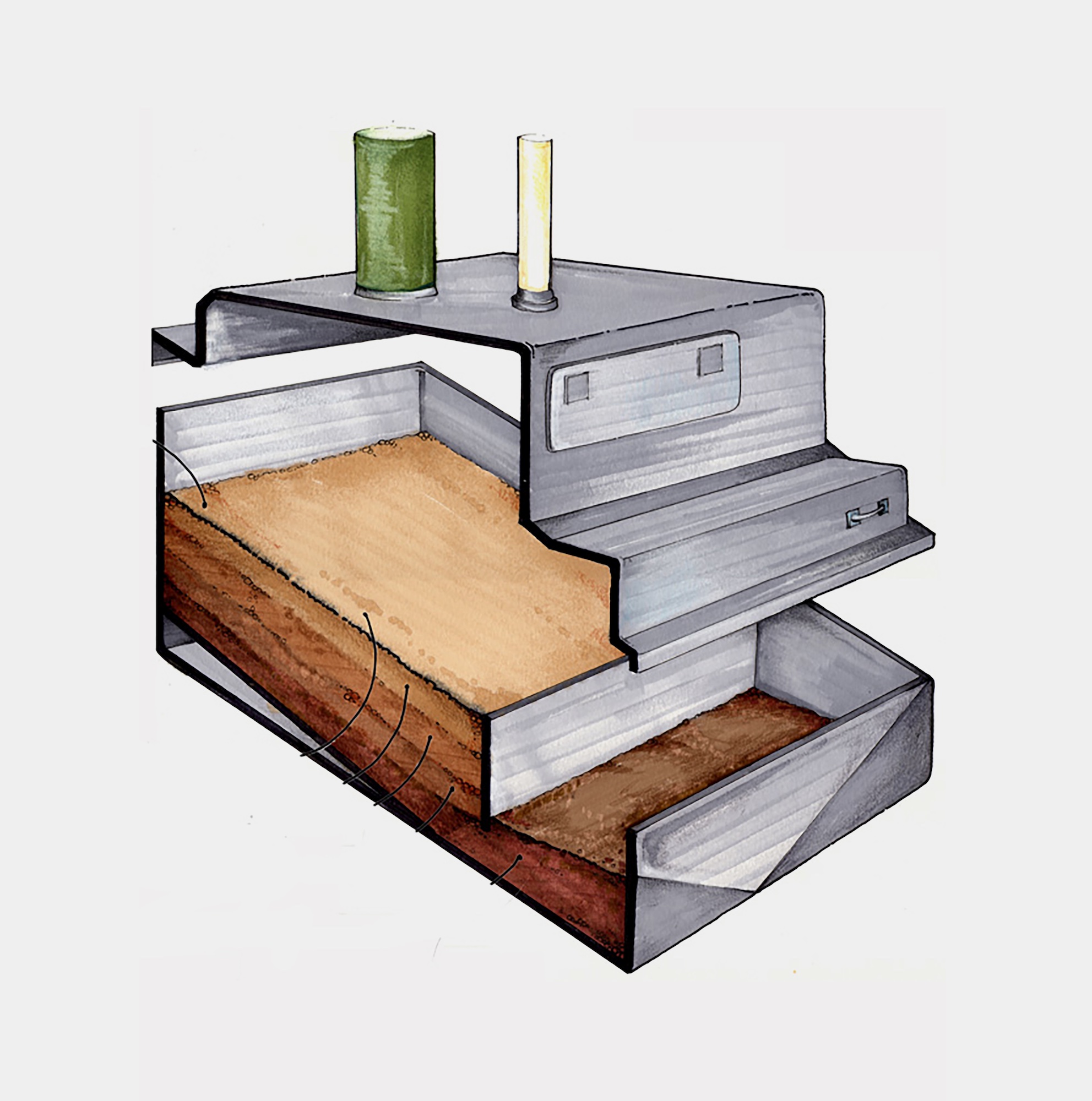

The Prince Edward Island Ark (1976), a collaboration between the NAI and Canada-based SolSearch Architects, was the institute’s first bioshelter to integrate residential space and provide a sustainable alternative to “orthodox housing.” One ambition of this inventive design was to implement a “microbial pathway” for composting and sterilizing not only agricultural waste, which the group had mastered in earlier efforts, but also human waste. Their solution: the Swedish Clivus Multrum dry toilet. Truly an aludel for compost, the Clivus Multrum transmogrified the Ark’s human waste into safe fertilizer within one year’s time. In the dark tank below the toilet, an internal ecosystem reliant upon organisms called chemosynthetic autotrophs broke down waste into nutritive material without creating any pollutive byproducts. According to the Alchemists, the “dry” technology of Clivus Multrum toilets had the capacity to reduce “water use by approximately ten-thousand gallons per person per year” and to “save [residents of densely populated urban areas] an estimated $40,000 in internal waste treatment,” in addition to providing nutrient-dense organic matter to support community agriculture and minimize sewage pollution.

Solsearch Architects and the New Alchemy Institute, aerial view of the Prince Edward Island Ark [courtesy of The Green Center / The New Alchemy Institute]

The New Alchemy Institute, illustrated diagram of a Clivus Multrum composting toilet [courtesy of The Green Center / The New Alchemy Institute]

Alchemically, the Multrum dry toilet creates a microcosmic space that reflects the transformative properties of the natural world; similar to the traditional Hermetic vase, it is a vessel that converts low matter into a precious substance. More practically, it conserves water, minimizes pollution, and saves money to provide a more sustainable, ecologically conscious alternative to past and contemporary waste management and infrastructure. The Multrum toilet demonstrates the New Alchemy Institute’s deep commitment to scientific inquiry and environmental design while hinting at the spiritual qualities of the institute’s name.5

Meredith Gaglio is an assistant professor of architecture at Louisiana State University. She received a PhD in architecture from Columbia University Graduate School of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation (2019). Her work addresses the development and implementation of sustainable community planning and architectural strategies in the US from the late 1960s through the early 1980s. Gaglio has received fellowships from the Graham Foundation, the Smithsonian Institution, the Canadian Centre for Architecture, and the Temple Hoyne Buell Center for the Study of American Architecture to pursue her research.

References

| ↑1 | John Todd, “Tomorrow is Our Permanent Address,” in The Book of the New Alchemists, ed. Nancy Jack Todd (New York: E. P. Dutton, 1977), 119 |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Manly P. Hall, The Secret Teachings of All Ages, 1928, reprint (Los Angeles: The Philosophical Research Society, 1995), CLIV. |

| ↑3 | Prior to Cashman and Ervin’s project, the New Alchemists used more traditional, slower composting methods and experimented with using the waste products of the tilapia they raised on-site as fertilizer. |

| ↑4 | Tyrone Cashman, “Confessions of a Novice Composter,” The Journal of the New Alchemists 3 (1976): 46. |

| ↑5 | Former New Alchemists Earle Barnhart and Hilda Maingay still advocate the use of dry toilets and urine diversion devices, especially as Cape Cod, Massachusetts, home of New Alchemy East, contends with algal blooms—a result of climate change and the island’s wastewater issues. See Christopher Flavelle, “A Toxic Stew on Cape Cod,” New York Times, January 1, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/01/01/climate/cape-cod-algae-septic.html for information on Cape Cod’s current water issues and newalchemists.net for more information on Barnhart and Maingay’s current work. |