Beverly Buchanan

Beverly Buchanan, “Three Familiar (A Memorial Piece with Scars), 1989 [courtesy of the Chrysler Museum of Art, gift of David Henry Jacobs, Jr.]

Share:

Between 1977 and 1985, the years she lived in Macon, GA, Beverly Buchanan could often be found at work in her airy, second-story, light- fillled studio on College Street. This little geolocational fact is more important than it may at first appear: College Street served as a de facto racial dividing line in Macon, separating the working- and middle-class black part of town from the middle-class and affluent white part of town. It was a mixture of grandeur and dilapidation; that Buchanan located her practice on this street makes a kind of sense, given her by then already well-formed sculptural language. Her sculptures reside in a similarly purgatorial space—between the made and the unmade.

At the time the understanding and reception of Buchanan’s work was bifurcated by these two Georgia viewerships. Her art was distributed and sold by a coterie of her good friends, most of whom were white, gay interior designers or restoration experts who dealt with a mostly, but not exclusively, white local clientele. As a result many homes in Macon still proudly display an original Buchanan drawing, print, or sculpture. Walk five to 10 minutes from the College Street studio to the historic black district of Pleasant Hill and you’ll come to Buchanan’s Unity Stones (1983)—an array of curved and rectilinear concrete forms that is now a patchy, blueberry hue, faded from its original, rich, matte black. The work sits in front of the Booker T. Washington Community Center, a building that most recently housed a STEM after-school program, and that has long been a historical site for the education of black children in Macon. While writing this essay I learned that the building had closed down. By press time, Macon’s NBC channel had announced that a “Downtown Challenge” project grant would be used to hire a consultant to “evaluate viable mixed uses” for the facility, but no local coverage had yet remarked upon Buchanan’s sculpture or what may happen to it. The sculpture is a gathering of intrinsically black forms—Buchanan often added black pigment to her admixtures of concrete—and a visualization of the black public it ostensibly speaks to. Heavy and solid, the work is nonetheless in a precarious phase of its existence.

This past year a retrospective exhibition curated by artist Park McArthur and Bogotá-based curator and writer Jennifer Burris has successfully reinvigorated interest and scholarship in Buchanan’s art and life. Having debuted at the Brooklyn Museum of Art [October 21, 2016–March 5, 2017] and traveled to the Spelman College Museum of Fine Arts, the wide-ranging exhibition featured video documentation of public sculptures similar to Unity Stones. Those works included Marsh Ruins (1981), a monumental creation located in the salt marshes of the Georgia coast, and Ruins and Rituals (1979), the work for which the traveling exhibition is named, located behind the Macon Museum of Arts and Sciences. These public works stand in relation to and in defiance of the historical genocide visited upon enslaved people of the US southeast coast, yet Buchanan carefully crafted her message so that it could be interpreted otherwise. In her proposal to museum leadership for Ruins and Rituals, for instance, she described that the work was to be about the play of light and color, rather than its careful siting near the reconstructed writing cabin of Henry Sitwell Edwards, a 19th-century writer who was most famous for a serialized fantasy that dramatized the voluntary re-enslavement of its protagonist. A set of large cement footings and small step-stones, Ruins and Rituals most resembles square sarcophagi—a public mourning for the black lives lost to the virulent racism of Edwards and his readers. Buchanan also hid a piece of Ruins and Rituals in the neighboring woods; she sank another component into a nearby body of water. As part of her art practice, she would drive—sometimes with her studio assistant, sometimes alone—to neglected graveyards for the enslaved and leave small sculptures. Sometimes she took photographs of these performative pilgrimages, but mostly she didn’t. The unseen, like the unmade, serves as the critical compliment to the heavy materiality of her public sculptures. To fully experience Buchanan’s work, viewers must dig for it.

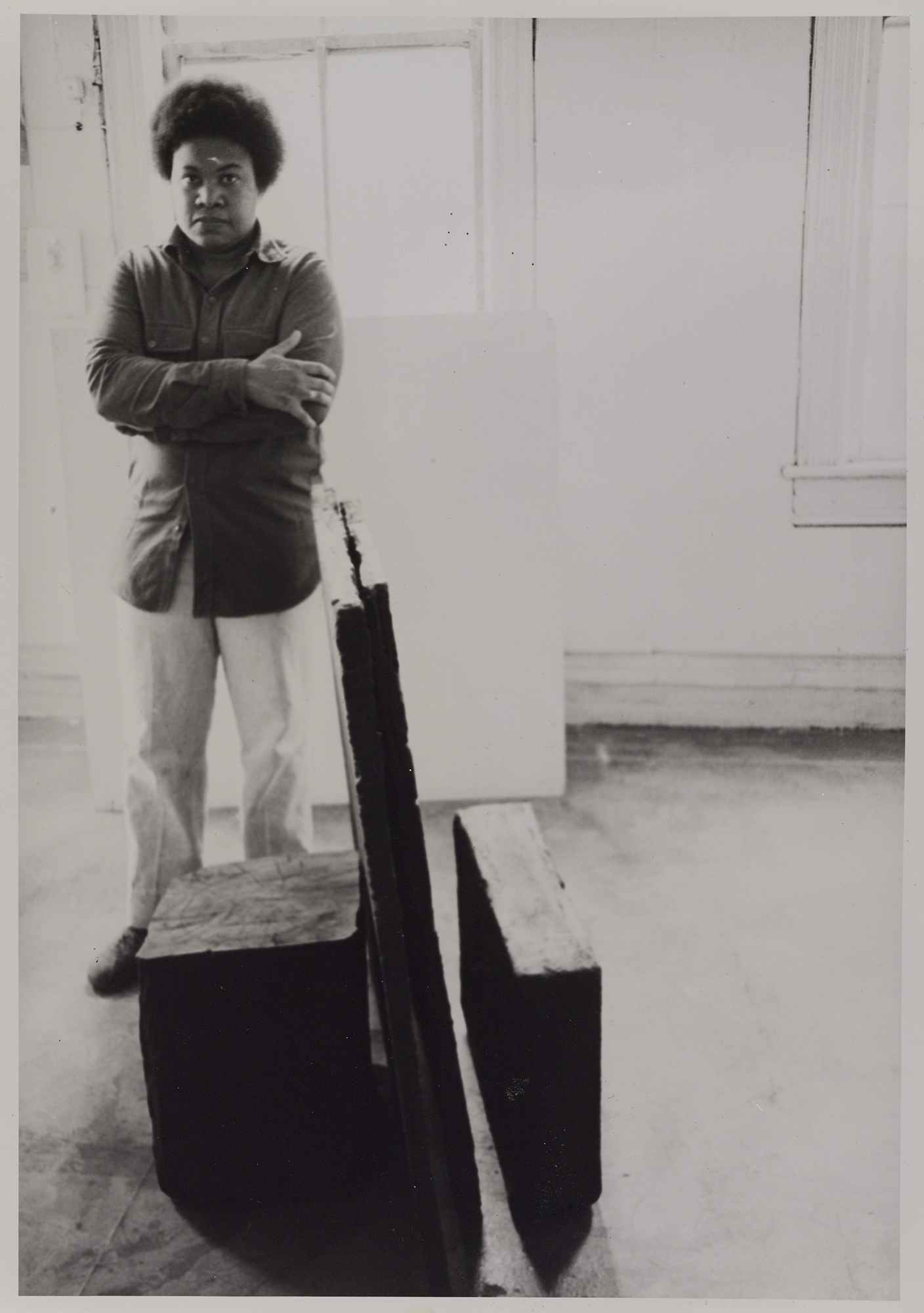

Beverly Buchanan, “Untitled [Portrait of the Artist], ca. 1978 [courtesy of Spelman College of Fine Art]

Elsewhere in the exhibition were artist’s books, postcards, fellowship applications, letters, drawings, and business cards, all pointing to a life filled with love and friendship, illness and hardship, and certainly humor. One postcard depicts Buchanan posing, only days after her move from the Northeast to Macon, next to a sign reading “Hunger and Hardship Creek.” It labels a real place, located near Dublin, Georgia. Buchanan wears pants and a long-sleeve button-front shirt with a vest. A smart bowler rests atop her afro as she bends her knee and grasps the sign, looking upward at it in an almost campy demonstration of the act of looking. It’s funny, but also not. Buchanan’s subversive approach makes everything feels atypical, fresh.

One archival item in particular seemed to typify the artist’s spirit and practice. A brightly colored business card, on which Buchanan advertises herself as a “Renaissance Woman,” lists her proficiencies: “Drawing, Magazine Modeling, Race Car Advocate, Painting, Yardwork, Sculpture.” A drawn self-portrait accompanies the description, and Buchanan depicts herself frontally, wearing sunglasses, her eyebrows arched. In each of these items Buchanan reveals a character capable of both irreverence and sharp commentary, here about the circumstances of what it takes to get by as an artist in the US.

Buchanan is perhaps best known for her later career sculptures of shacks, some inspired by the actual homes of the rural poor, others invented. As a child Buchanan accompanied her father, who was the dean of the School of Agriculture at South Carolina State College, as he ventured out to meet the farmers and sharecroppers in the Cotton Belt; and so these shack sculptures are deeply tied to her upbringing. About a year ago, after publishing an article on Buchanan, I was contacted by an auction house selling one of these works and wanting to know if I were interested. I was, but feared I wouldn’t have the requisite funds. The auction house had undervalued the sculpture significantly, bringing it within reach. I won the work. Weeks later the sculpture arrived at my apartment. The work’s foundation was in disrepair, crumbling under the weight of its materiality. Little pieces of the sculpture, elements Buchanan had intended to be placed here and there in the shack’s “yard,” were carefully packed away in a Ziploc bag. Unwrapping the house from its protective padding yielded a surprise: the drawn figure of a black woman standing at the door. Drawings or assemblaged black figures sometimes show up in these sculptures. But photographs from the auction house depicted the work from only two sides, leaving out the figure—a grim confirmation of the erasure of artists— brown, queer, black, trans, disabled, poor, chronically ill, female—persisted by our arts institutions.

Curator Lowery Stokes Sims has rightly noted that Buchanan’s sculptures “seem to defy the exigencies of our immediate history.” To this truth I would add that they serve as evidence, too, of the proximity of the past, and the deep degree to which it informs our contemporary moment.

Untitled, glass bottle, wood, license plate, 17.74 inches x 10 inches, collection of Spelman College, gift of Lucinda and Robert Bunnen

Untitled (Red Ladder), 1995, wood and mixed media, 17.75 x 10 inches, Spelman College Museum of Fine Art, gift of Lucinda Bunnen