Below Baldwin

Protestors stand behind University President Jere Morehead as he speaks about the dedication of the Baldwin Hall monument [screenshot courtesy of the author and Joe Lavine]

Share:

In 2015, renovations to the University of Georgia’s Baldwin Hall revealed 27 graves near and beneath the foundation of the building. Eventually, 105 graves would be discovered. The documentary Below Baldwin, directed by Joe Lavine and narrated by Athens-based artist Broderick Flanigan, was created in response to the unearthing of these graves. DNA testing and archeological research revealed that most of the bodies to be predominantly of African descent. According to the film, architects possibly knew about this cemetery while building Baldwin Hall, home to UGA’s anthropology and sociology departments, among others. After this most recent discovery, archeological studies revealed that remains from the cemetery were upset or destroyed during the initial construction of Baldwin Hall and subsequent renovations and landscaping, before the most recent discovery.

In Below Baldwin, Flanigan narrates reports stating that before Baldwin Hall’s construction, the graves were shallow, few were marked, and often just an indentation in the ground indicated what lay below. When heavy rains occurred, bones from graves closest to the edge of the cemetery would run into the street. But this narrative and that of the lives of people who were enslaved often go untold or inadequately told. The stories of slavery in Athens, GA, as well as of these buried people are part of what can be called the unhistoried: narratives of violence that have themselves been buried, made polite or silenced. Below Baldwin provides a non linear, oral and visual history for (re)historying these Athens narratives.

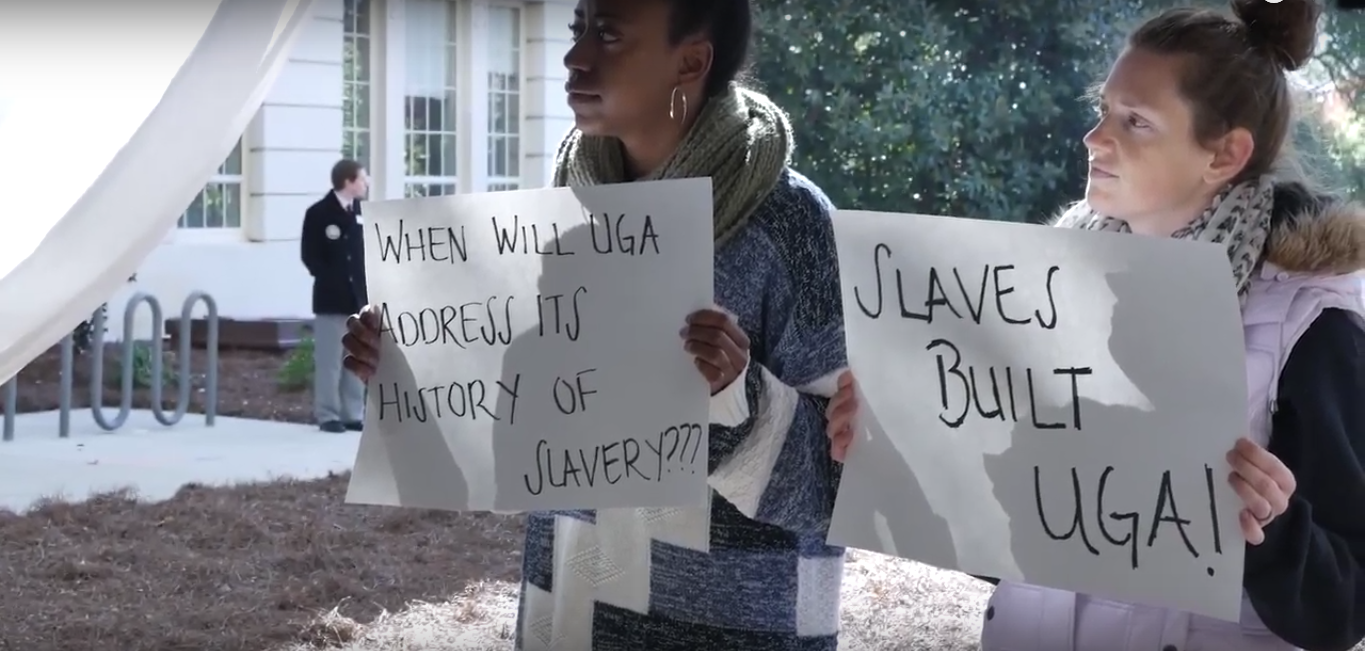

In its depictions of protests, documents from the founding of UGA, and a chronology of events surrounding the discovery of the graves, Below Baldwin captures the tensions and narratives that were revealed by literal resurfacing of history. Interviews with community leaders Fred Smith, Linda Davis, Linda Lloyd, Mariah Parker, and others present oral histories of frustration, grief, hope, and resilience. The film also spotlights UGA and the surrounding Athens area’s abundance of radically resilient activists and communities of color.

Linda Davis, Coordinator for Friends of Brooklyn Cemetery [screenshot courtesy of the author and Joe Lavine]

“Just tell it all,” states Fred Smith Sr., co-chair for Athens Area Black History Committee, in the opening shots of Below Baldwin. He recounts the story of the day the buried bodies were exhumed and moved without the consultation of communities of color in Athens, and he comments further: “For some reason we don’t want to deal with slavery history. Or some folks don’t want to deal with it.” The University reburied the bodies and constructed a monument at Baldwin Hall in memory of the deceased found under the building. Below Baldwin includes scenes showing the dedication of the monument: University of Georgia’s president Jere Morehead describes the commemorative plaque while placard-bearing protestors line up behind him. Their signs address what they deem contemporary results of UGA’s history of slavery: pay at less than a living wage for some people working at the school and the institution’s low percentage of students of color. Joe Fu, a founding member of the United Campus Workers of Georgia union states that “the only way you can characterize this [monument] is [as] a kind of white wash. It’s trying to separate the epic of slavery into some kind of quaint period that ended long ago. Whereas, in fact, if we look at the community of Athens, it’s pretty clear that oppressive labor practices and racialized labor practices have persisted from the days of slavery through the days of Jim Crow into the present.” In the film’s next scene, Linda Lloyd states, “Now what I say with the employees [who] do not make a living wage with health benefits, [is] that they are working for slave wages. So, in a sense, it’s a kind of a slavery.” Mariah Parker, District 2 commissioner for Athens-Clarke County, argues that UGA must acknowledge its history of slavery, change its system of supporting faculty and staff of color, and create reparational scholarships for communities of color who live in Athens.

Linda Davis, coordinator for Friends of Brooklyn Cemetery, states in the documentary that “Baldwin Hall is sitting on top of a cemetery, and it’s a cemetery of the people in this community, in this world, who are the least among us, who had no rights, who had no privileges. We were owned. We were [part of] chattel slavery.” She describes the potential to determine her ancestry from the DNA of the bodies found under Baldwin Hall. She speaks also of a radical resilience—the refusal to be declared dead. These bodies and their history are living memories.

Below Baldwin’s arrangement of narrative through its composition of shots shifts notions of time and challenges chronological models of narrative. It declares that the past doesn’t stay in the past; History continuously presents itself as current, not as a repetitive phenomenon, but as a circular model wherein stories from the past still live and communal memory can encompass an entanglement of history. In this model of time, the relevance of a community’s narrative does not pass away. It’s always alive.

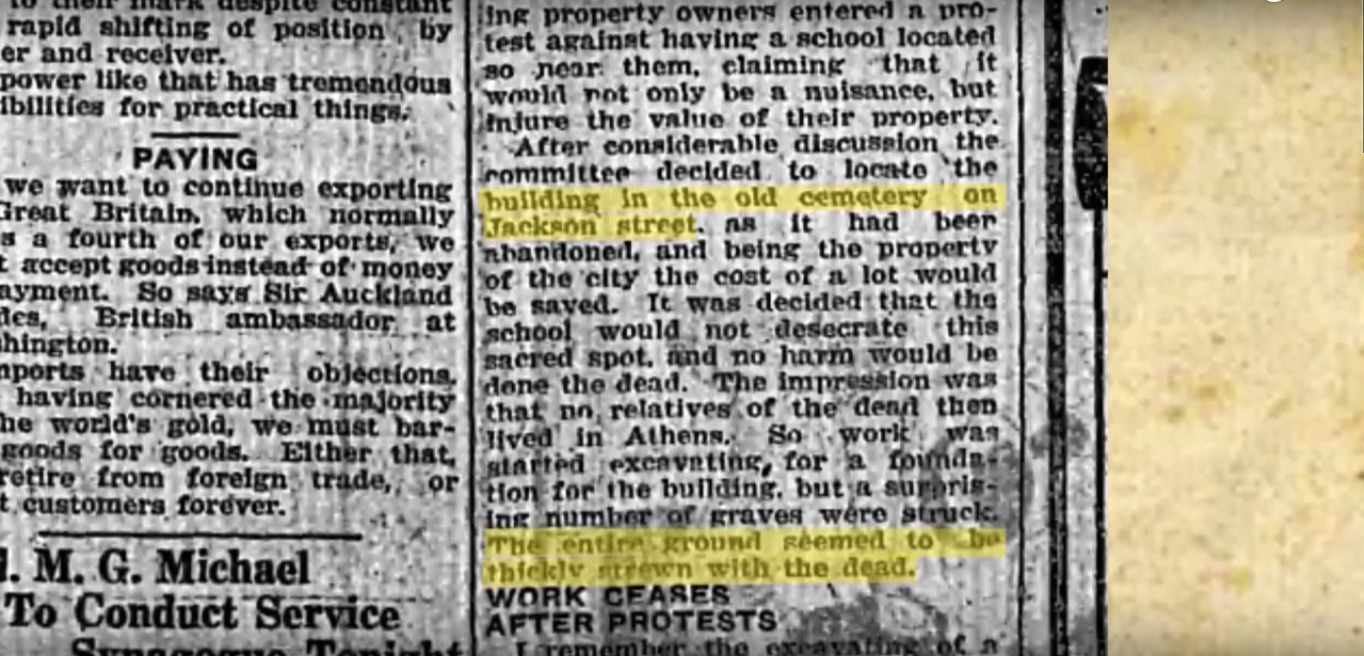

Below Baldwin presents a unique opportunity to tie the ends of time together through compositions that set different periods side by side. This cinematic method weaves intricate narratives that employ verbal and nonverbal language. Broderick’s voice narrating the legacy of slavery in Athens history is set over archival footage of protests at the dedication ceremonies for the monument now standing at Baldwin Hall. Documents from UGA’s founding are juxtaposed with scenes of protestors’ messages scrawled with black Sharpie on white poster board. Slavery is spoken about in the same breath as current forms of economic and literal (economic) bondage of communities of color and black communities. Several different stories intersect without usurping one another. Space and time spread before the viewer, demonstrating a method for the development of oral stories that present longer, more complex memories within communities.

Old documents regarding early interactions with graves during the initial construction of Baldwin Hall are depicted in Below Baldwin [screenshot courtesy of the author and Joe Lavine]

Below Baldwin is a piece of social artwork that comes at a pivotal time in US history, when previously rigid forms of narrative legitimacy are being dismantled through unearthing the histories of slavery. Knowledge production is shifting in radical ways. The communities of Athens face several challenges—ones that are not unique but that are worthwhile. What do we do with all of the histories beneath our feet? How can art of different mediums speak across time and account for a multiplicity of narratives? How do these narratives press into the future? Below Baldwin is a creative solution, but it also expresses a weariness that in such situations as the one it details, creativity is often not the first choice of action. In the film, Alvin Sheats, president of Athens NAACP, states, “There’s no rest, even after this life. You still can’t get proper consideration. And it looks like to me, with all our wisdom with engineering and building, that we could have—we actually could have left those bodies in place and created a memorial-type garden, either around or underneath the development.” Fred Smith goes on to say, “Here, if it grows it knows its place in history.” (from Danez Smith’s poem summer, somewhere). Below Baldwin is helping to plant the seeds for that growth: a radical resilience that might one day provide rest.