Behavior Conditioner: The Narrative Imagination of Ian Cheng

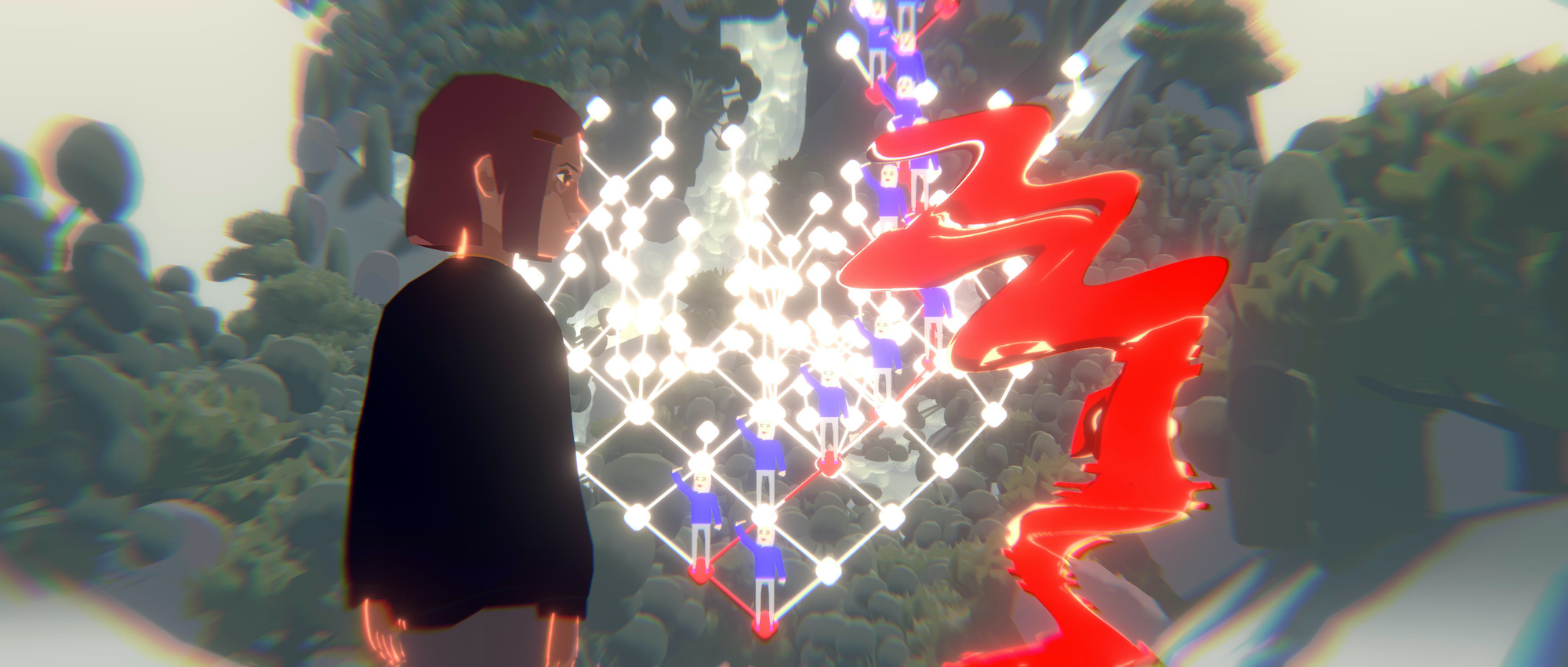

Ian Cheng, Life After BOB: The Chalice Study, 2021-2022, real-time story and simulation, 50min, color, sound [courtesy of the artist and Metis Suns]

Share:

The inscrutability of the universe is quite enough for us to think about.

—Fernando Pessoa, The Book of Disquiet

After taking up the primordial past and the post-apocalyptic future in a previous body of work, Ian Cheng has set his latest animation within a relatively near-term eventuality of our current preoccupations. The futurity of Life After BOB: The Chalice Study (2021), like the present into which it arrives, is presided over by underdeveloped and overweening info-industrialists, who toy blithely with the fate of humanity while yammering about “life scripts” and “total divine potential.”

In the second half of the 21st century, a neural engineer, Dr. James Moonweed Wong, his research stymied by more cautious executives, uses his 10-year-old daughter, Chalice, as a test subject for an experimental procedure. He augments the girl’s nervous system with an artificial intelligence called Destiny BOB, which is intended to closely chaperone her formative years. It exists somewhere between imaginary friend and superego—a high-powered, dependency-forming Jiminy Cricket.

In an accident of youthful rebellion, Chalice abdicates a decade of her life to this rapacious autopilot. She finally regains consciousness on her wedding day to confront the software that has hijacked her body and changed her name. The twisting plot culminates in the pre-sale of the cognitive asset to an extraterrestrial sisterhood. Chalice is the display model and spokesperson, in possession of newfound public-speaking abilities. Asked what she’ll do next, she says she looks forward to selling her memoirs.

Ian Cheng, Life After BOB: The Chalice Study, 2021-2022, real-time story and simulation, 50 minutes, color, sound [courtesy of the artist and Metis Suns]

The work’s premise is genuinely terrifying. It rushes at you all at once, in a comically dense introductory text and in quick, lively dialogue, and demands repeat viewings to understand its intricacies. The lambent polygons that constitute the animated images are deployed with brilliant economy, like cut-paper illustrations. The imagery is evidently inspired by anime artists such as Hayao Miyazaki, but it maintains a look and logic of its own. The outsized character of the renegade CEO, Z (short for Zoroaster, after the prophet), is so distinctive and charismatic as to recall franchise players such as Robin Williams’ Genie or Kool-Aid Man. The rich fictive world teems with stories to tell, in addition to Chalice’s. One might eye the colon in the title and anticipate an expanded universe. (The series is currently planned to have eight parts.)

The Chalice Study is Cheng’s first traditionally scripted narrative work, though it is not a traditionally produced animation. Each 48-minute loop is another iteration of a program built in the Unity video-game engine, which renders the episode in real time, admits small variabilities, and—in theory—allows for the movie to continue being developed on the fly.

Cheng has been using Unity for at least 10 years to create simulations: computer animations with no set sequence or duration, which play indefinitely, and always differently. In 2018, he used it to create what he refers to as an artificial lifeform. His spiny red worm is called BOB, short for Bag of Beliefs—a precursor to the AI of the same name that robs Chalice of her youth. In this earlier iteration, BOB is placed in the care of gallerygoers, who use their smartphones to offer it food and wisdom in the form of koans, the syntactical units selected from a multiple-choice menu. BOB feeds on its viewers’ tutelage as it grows older and larger, encounters difficulties, makes decisions, and ultimately dies, setting the cycle in motion again.

Although Cheng’s early work was more formal than narrative, based upon the emergent behaviors of systems, he has steadily been working back toward the role of artist as storyteller. In The Chalice Study, Cheng presents a fantastically harrowing vision—the colonization of human consciousness—by thematizing the implications of artificial intelligence, which previously constituted the actual matter of his work. In interviews, Cheng anticipates that such technology will continue to accelerate unchecked, becoming ever more entwined with the human and leaving the individual to “surf” (or drown, one imagines) in the “choppy waters.”1 The artist’s rosy disposition about such a prospect presents an opportunity to consider more closely the stakes of his practice and the place of the viewer therein.

_____________________________________________

Ian Cheng, Life After BOB: The Chalice Study, 2021-2022, real-time story and simulation, 50min, color, sound [courtesy of the artist and Metis Suns]

Two bits of biographical detail seem to find their way into every piece of writing about Cheng’s work: that he holds an undergraduate degree in cognitive science, and that—in the year between completing college and beginning an MFA program—he worked for George Lucas’ Industrial Light & Magic effects studio. It’s easy to see why these credentials are so often mentioned; together, they appear to chart the contours of Cheng’s current practice, which combines a long-standing interest in artificial intelligence and machine learning with an enterprising impulse toward iterative world-making and fabulation. 1

Before he made worlds, Cheng cast about for ways to synthesize his interests. Early videos demonstrate his experiments with datamoshing and motion capture. His first simulations are likewise sketches, depicting garbage heaps of used ideas. He occasionally borrows from existing intellectual property to lend some frisson to these images: crude versions of Bugs Bunny and Elmer Fudd hopelessly entangled, a misshapen female figure in a Charlie Brown T-shirt.

In Chuck Jones’ Duck Amuck (1953), Daffy Duck sallies out of a Three Musketeers bit and onto the void of a blank drawing pad, where he protests the unprofessionalism of the animator. Cheng’s earliest simulations, Entropy Wrangler and Thousand Islands Thousand Laws (both 2013) are likewise set against the clean slate of their production process—in this case, the grayish background of a 3-D–modeling environment. Unlike the classic Merrie Melodies short, Cheng’s initial forays into simulation don’t quite crystallize form and concept. Their falling, floating, and flailing figures and objects—potted plants, cinder blocks, two-by-fours, dinosaurs, a flock of herons, a gunman, the earth, the moon, and other castaways from the stock-model warehouse—behave according to various scripts. The animated characters react to the other elements in the frame but certainly do not look beyond it to pose questions and demands of the intelligence that created them. This formula produces occasional moments of interest within a predictably chaotic cluster of hyperextended limbs and stochastic twitching. On the soundtrack, the tinkling glass, metallic thuds, elastic twangs, and the hiss of compressed air being released give the sense of notification chimes, though the viewer is left to wonder what activity they signify, if any.

Before long, Cheng deemed these works “lacking in meaning.” They suggest something “dynamic and evolving,” he has said, but “with zero perspective on what it means to evolve.”2 He continued to develop his visual vocabulary and began to include the voices of AI bots in voiceover, sometimes combining them to create inane conversations. There are indications present of the direction Cheng would take, but the work has more affinity with glitch art than with speculative fiction or systems and process practices. These simulations, sputtering with promise, are perpetual-motion machines gone haywire, not the more delicate ecosystems Cheng would soon be making.

_____________________________________________

Ian Cheng, Emissary in the Squat of Gods, 2015, live simulation and story, infinite duration [courtesy of the artist, Metis Suns, Pilar Corrias, London, Standard (Oslo), Oslo, and Gladstone Gallery, New York]

Cheng’s big breakthrough came in 2015. By adding a narrative agent—a figure that was not only reactive but proactive, programmed to pursue certain ends amid the rollicking fray—he found that he could imbue his simulations with the semblance of drama.

In the Emissaries trilogy (2015–2017), the same parcel of earth plays host to three very different societies over the millennia, as the surroundings change from volcano to pasture to atoll. The trilogy is, Cheng has said, “dedicated to the history of cognitive evolution, past and future.”3 Although the simulations themselves are not strictly narrative, their premises have everything to do with the conditions from which myth, story, and consciousness may have arisen, and where they might be found in a few leaps of time and faith. The emissaries are the narrative agents, determined to carry out their scripts: a young girl trying to persuade her community to migrate away from the danger of an eruption; a Shiba Inu dog, kept as a pet by a godlike AI and tasked with extracting the memories of a reanimated 21st-century celebrity; a golden puddle that possesses a mutant plant and invokes the ire of its groundskeeper congregants.

In interviews and writing, Cheng talks about using such simulations to illuminate “nonhuman-scaled complexity.”4 Climate change, financial crisis, religious schism, mass migration, big data—all organize the structure of human experience but are so massive as to defy human understanding. Traditional fiction forms cannot properly model the density of these events, their moving parts, their infinite contingencies. They are, Cheng has said, “impervious to narrativization.”5. Perhaps, instead of being told, he suggests, the stories of our age must be simulated.

Ian Cheng, Emissary Forks At Perfection, 2015-2016, live simulation and story, infinite duration [courtesy of the artist, Metis Suns, Pilar Corrias, London, Standard (Oslo), Oslo, and Gladstone Gallery, New York]

The materials list of each Emissaries work reads: “live simulation and story, endless duration, sound.” Indeed, the story one reads about the work is quite distinct from the simulation one watches; it would be difficult to divine the former, having seen only the latter. As should be obvious from their synopses, these vignettes are bursting with ideas, probably too many for each of them to carry capably. As in Cheng’s earlier experiments, there is a busyness, and an arbitrariness, to the movements, though the tenor and the pace are far more precise. Programmed for dynamic functionality, these simulations—in the course of their actual running—incur a kind of stasis. Watching them is a bit like studying a fishbowl or a terrarium: closed systems in which the natural behaviors of organisms are distorted as they adapt to captivity. Cheng prefers the metaphor of a tide pool, though in this case there is no oceanic medium to periodically refresh the ecosystem with external inputs.

As freighted with metaphysical and narrative import as Cheng’s creatures are, as varied their morphologies, it is immediately apparent to the human eye that no intelligence exists behind their movements, other than that of their author. The simulations are lovely, but dull to watch (another reviewer has called them “absorbing and tedious”6. Suspension of disbelief, the cognitive leap so foundational to narrative as a technology, is not yet possible here.

To accompany his first solo museum exhibition, at MoMA PS1, in which the Emissaries trilogy was shown, Cheng published an informational brochure. Designed to imitate National Park Service literature, it synopsizes each episode’s story, provides a bestiary of the characters, and illustrates the cognitive pathways of their decision-making with a surfeit of flowcharts. The effect of this handsome pamphlet is, in part, like that of a “show your work” proof for a difficult equation. It serves the dual function of illuminating the simulations and impressing upon the viewer the elaborate planning that went into their construction.

Written language surrounds and supports the imagery, which would be only partially legible without it, aligning the work somewhat more with the tradition of conceptualism than with new frontiers of cinema. “The sense of emergent behavior was very beautiful and very surprising for me as an artist,” Cheng has said, “but I found that it was very difficult to understand what any of it meant.”7 (Cheng is admirably frank about the perceived failures of previous work.) His projects to come would rely far less on the museum or gallery as an explanatory armature, though they would continue to be sited in the institutional art world and to make use of its funding streams.

_____________________________________________

Ian Cheng, BOB, installation view, 2019 [courtesy of the artist, Metis Suns, and Gladstone Gallery, London]

After completing Emissaries, Cheng spent two years developing the aforementioned BOB (Bag of Beliefs) (2018–2019). The titular lifeform, dwelling in the gallery space and visiting the “shrines” visitors construct on their smartphones, is essentially an elaborate Tamagotchi. Its innovation is the “congress of demons” that governs its decisions—modeled after Immanuel Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason (via the AI scientist Richard Evans) and the psychoanalytic work of Carl Jung.

That the artist and the technologist should be imagined as entirely distinct social and professional categories is a relatively recent proposition, owing to the industrialization and specialization of both fields. For the ancient Greeks, technē referred to all mechanical arts. In the 15th century, Leonardo da Vinci sketched an early precursor to the modern helicopter in the same notebooks where he painted pea pods and cherries. In our own time, the scientist and the so-called “creative” are arrayed against each other. From the classroom to the corporation, where they are often sequestered in different wings, they are supposed to be as diametrically opposed—and yet so perfectly complementary—as the hemispheres of the brain that rule their respective bearings. Ironically, the livelihoods of both are threatened as artificial intelligence becomes increasingly capable of writing code and copy, making images and engineering decisions—all with the benefit of five thousand years of human knowledge, of course.

Beginning in the 1960s, the Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.) program put prominent visual artists, composers, and choreographers in league with research engineers at Bell Labs. The first iteration of this program culminated in interdisciplinary performances featuring such novelties as remote-control dance platforms, Doppler sonar devices, and early video projections. That legacy continued in Rhizome’s Seven on Seven series—daylong development sprints pairing artists and technologists, in which Cheng has participated. Such collaborative models, intended as a corrective to the division of talent elsewhere, serve also to reinforce the discrete roles of both types of participants. The resulting productions are sometimes trite, sometimes fascinating, but in either case they help to condition public acceptance of—and enthusiasm for—the imposition of new technological regimes.

Ian Cheng, BOB, installation view, 2019 [courtesy of the artist; Metis Suns; and Gladstone Gallery, London]

More recently, Cheng dipped a toe into the then-booming and now-busting trade in nonfungible tokens (NFTs), digital assets (sometimes artworks) authenticated by the same blockchain technology used to “validate” cryptocurrency. Upon purchase, Cheng’s 3FACE (2022) generates a portrait of its collector, using as inputs everything else in the buyer’s digital wallet transaction history. The result is a unique image, owned by its subject and designed to flatter and fascinate them. This tactic recalls classical portrait commissions, which were often as much an inventory of the sitter’s possessions as an index of their physical appearance. The more obvious resonance is with the ongoing vogue for personality tests and horoscopes as markers of identity among those marked otherwise mostly by their material wealth.

It is difficult to know where such an artwork falls on the spectrums between pathbreaking and conformist, earnest and opportunistic. We might imagine these qualities outlined on a 2×2 matrix, a form to which Cheng often refers; its quadrants would, perhaps, be labeled Invention, Innovation, Pablum, and Parody.

_____________________________________________

The Chalice Study includes an interactive component. At The Shed, after viewing the single-channel, set-duration movie, viewers could discover an identical screen-and-riser setup behind where they sat. On that side of the room, the visitor was invited to use their smartphone as a remote control to pause, rotate, and examine more closely the scenes of the animation. Selecting certain objects called up on-screen text with information about them, apparently derived, in part, from a user-generated wiki. Changes to that data set would result in changes to the animation itself, the exhibition materials announced. Cheng refers to it as WORLDWATCHING, “a revolutionary, interactive way to explore the world of the movie.”8

I saw the show twice, with more than a month between visits, and was disappointed not to detect any noticeable difference between the first set of viewings and the second. In a video promoting the exhibition, Cheng clarified, “Edits that you make will influence some of the cosmetic and later behavioral changes of those objects, that will then play live.”9 As an example, he suggested that some of the background characters would acquire attributes assigned by users. The wiki pages of the animation’s operative elements (main and secondary characters, props, settings, etc.) are protected from user edits, and the whole site sits dormant at the time of this writing, although the work has been touring the world for almost three years.

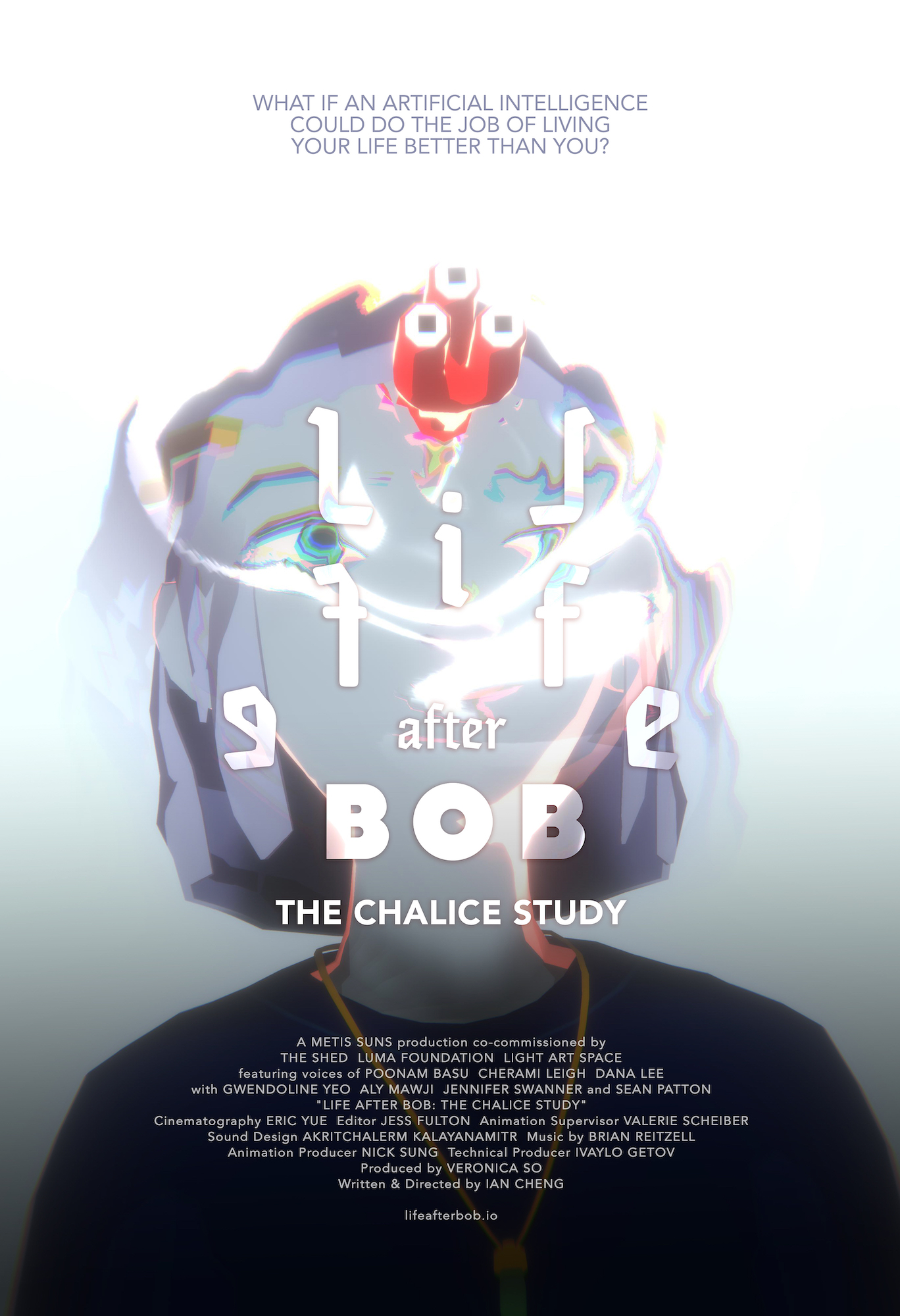

Ian Cheng, Official Poster for Life After BOB, 2021-2022, real-time story and simulation, 50min, color, sound [courtesy of the artist and Metis Suns]

The yawning gap between promise and delivery of this particular cinematic gimmick is not so offensive on its own. Such exaggerations have a long history in the cinema of attraction, and in showcraft more generally. This interactivity feature, being subject to production constraints, seems still to be more dream than reality. The opportunity to fill in the lore of a fantastical universe might interest some fans, even if they knew their contributions would be effectively tooltips on small pieces of background scenery. For now, we can imagine the possibilities given a prototype with much reduced functionality. In Cheng’s larger body of work, however, the question of the viewer’s place is already vexed. A mostly notional sop to user participation seems out of place in a practice oriented around a strong, singular authorial voice.

For the exhibition of the work in Berlin, visitors were invited to mint free NFTs, which combined a screenshot from The Chalice Study with an algorithmically produced honorific based upon the viewer’s name (“Anna the Producer,” “Jacob the Beacon,” “Marianna the Faithful,” etc.). The availability of such a souvenir, like a Mickey Mouse magnet with a child’s name on it, reinforces the exclusive roles of producer and consumer in relation to the work—a familiar, restrictive dynamic.

Ian Cheng, Life After BOB: The Chalice Study, 2021-2022, real-time story and simulation, 50 minutes, color, sound [courtesy of the artist and Metis Suns]

Where Cheng has previously solicited participation, the experience has often been one of supplication or subservience. Emissary Forks for You (2016), a spinoff of the Emissaries trilogy, allows viewers to chase the Shiba Inu character around the galleries via tablet computers. As viewers obey the dog’s command to follow, they hear the sound of an animal trainer’s clicker, the kind used to reinforce good behavior. Cheng sees this farce as a case of an artificial intelligence programming human action, rather than the other way around: “You are its pet.”10 In another work, Bad Corgi (2016), the artist’s only playable video game to date, the player attempts to control a disobedient dog, which in turn struggles to contain and protect a herd of sheep. The resulting frustrations are perhaps the objective of what Cheng has called a “shadowy mindfulness tool.”11 One reviewer notices that “The system seems to work better when I am not involved at all,” though she sees this tack as an ingenious one for “interrogating the promise of digital smoothness.”12 Describing the version of his AI that derived sustenance from gallerygoers, Cheng has said, “You are there for BOB to consume or reject you as a viewer. … BOB is not there for you.”13

An artist is not obliged to provide hospitable conduits for a viewer to enter and effect changes upon their work. If some expectation of interactivity exists in the case of networked animation technology, it is mostly because such exchange is possible. Cheng’s WORLDWATCHING conceit may represent an overcorrection, a desire to have his story and simulate it too. The artist’s latest work activates the emotional response of an audience to traditional characters and plot but attempts to maintain the novel sense of genre-defying exploration and technological dexterity that have enlivened previous efforts.

Leaving the questionable application of audience engagement schemes to one side, The Chalice Study is easily the most engrossing work of Cheng’s career, the result of a long and deliberate move to narrative. In his simulation works, which Cheng frequently describes as “video games that play themselves,” there is nowhere for viewers to involve themselves in the system, even at the interpretive level. The project of making meaning from aesthetic experience—typically shared between the artist, the viewer, and the context by which the work is mediated—is cordoned off by Cheng’s prodigious intelligences, artificial and otherwise. One might better understand these works by delving deeper into the documentation for their intricate designs, but to think alongside them would be difficult, as each has already been conceptualized to completion. Cheng uses the term “worlding” to describe his preferred creative methodology: “the art of creating and parenting a web of relations.”14 In his formulation, this exploration is, strangely enough, an activity for one.

Ian Cheng, Life After BOB: The Chalice Study, 2021-2022, real-time story and simulation, 50minutes, color, sound [courtesy of the artist and Metis Suns]

Despite Cheng’s expansive curiosity and ambitious fabulation, determinism lurks at the heart of his project. In his worlds, intelligence is only programmatic, life is only a series of decisions, and the human is only a particularly complicated collection of competing needs and desires. These limitations remain evident in The Chalice Study, but now the dissonance between their cold logics and the lived experience of a viewer becomes the dramatic engine that compels one’s involvement in the story. Paradoxically, at its most formally coherent—even at its most conservative—Cheng’s work begins to open up to its audience, who may respond to its provocations with more variability than anticipated by the artist in his souvenir and suggestion-box feedback mechanisms.

Maxwell Paparella lives in the city of New York

References

| ↑1 | “Building Worlds and Creating New Fairytales,” interview with Ian Cheng, The Shed, September 21, 2021, video, online. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Ian Cheng, “The Artist and His Killjoy,” interview by Veronica So, Office, 2017, online. |

| ↑3 | Ben Vickers, “Hermetic Engineering: The Art of Ian Cheng,” Artforum, March 2016, online. |

| ↑4 | Ian Cheng, “Artists and Critics on Animation,” Artforum, Summer 2014, 331. |

| ↑5 | Ian Cheng, “Infinite Game of Thrones,” in The Machine Stops, ed. Erik Wysocan (New York: Halmos, 2014) |

| ↑6 | Andrea K. Scott, “Watch the Absorbing and Tedious Simulations of Ian Cheng,” The New Yorker, May 16, 2017, online. |

| ↑7 | “Building Worlds and Creating New Fairytales,” The Shed. |

| ↑8 | “Life After BOB: The Chalice Study,” official website, online. |

| ↑9 | “Building Worlds and Creating New Fairytales,” The Shed. |

| ↑10 | Alex Greenberger, “The Cyborg Anthropologist: Ian Cheng on His Sentient Artworks,” interview with Ian Cheng, ARTnews, March 31, 2016, online. |

| ↑11 | “Ian Cheng: Bad Corgi,” Serpentine Galleries, 2015, online. |

| ↑12 | Nora N. Khan, “Trust Issues: Ian Cheng’s app resists digital smoothness,” review of Bad Corgi, by Ian Cheng, Rhizome, May 3, 2016, online. |

| ↑13 | Ian Cheng, interview with Hans Ulrich Obrist, quoted in “Ian Cheng,” by Reinaldo Laddaga, review of BOB, Gladstone Gallery, 4Columns, February 22, 2019, online. |

| ↑14 | “faq,” Ian Cheng, official website, online. |