Members of AT&T Dolphin Celebration, 2016 [courtesy of Georgia Aquarium]

Atlantis, GA

Share:

The beluga exhibition at the Georgia Aquarium in Atlanta features three whales, kept in a double-height, 800,000-gallon tank. Visitors can walk up to the glass and see these marine animals face to face, while remaining dry—a technologically enabled experience unavailable to humans before the mid-19th century. Standing in the dark, illuminated by a glimmering sea-blue light, people of all ages watch transfixed as the whales circle in the water with movements alien to terrestrial life. Facing the tank is a second-floor viewing platform, where a light box featuring text is affixed to the railing. The triangular logo of Georgia-Pacific, a Koch Industries subsidiary known for its pulp and paper products, is on the upper left corner. On the right is an illustration of a beluga whale with 15 white squares depicted along its ventral length. Below, through a window in the light box, is a roll of toilet paper, branded “Quilted Northern Ultra Plush.” The accompanying text reads: “Did you know? A beluga is born dark gray and about 5 feet (154 cm) long: That’s as long as 15 rolls of Quilted Northern Ultra Plush Bath Tissue lined up together!”

It is difficult to disentangle the various frames through which to analyze this presentational moment: if it is purely exploiting an opportunity to promote toilet paper, then the effort to display live whales seems outsized, if not unethical. As an educational tool, the text lacks basic information about the animals, to say nothing of its unusual unit of measurement. As media for entertainment, the narrative intention is opaque, as is its audience.

Opened in 2005, the Georgia Aquarium—the largest in the world until the Marine Life Park in Singapore opened in 2012—is a 501(c)3 nonprofit organization. It was founded with a gift of more than $250 million from Bernard “Bernie” Marcus, the co-founder of Home Depot—the largest company in Atlanta (bigger even than Coca-Cola, the other hometown corporation).1 The Georgia Aquarium still maintains the single biggest tank in the world, where it features whale sharks—the biggest fish in the ocean. It is the only facility not in Asia to have these bus-sized animals on view. Facts and figures aside, however, the Georgia Aquarium resists any simple description. To experience it is to be submerged in multiple, superimposed global systems: from the ecologies of the oceans and their attendant geopolitics, to the financial, philanthropic, and urban development networks of an ever-changing downtown Atlanta. These systems operate in tandem for many purposes, in Atlanta and elsewhere—with the seafood trade, and with international shipping—but at the Georgia Aquarium, they create a direct experience where the contingent parts remain quietly legible as they combine and recombine throughout the building. Eating a piece of codfish served in the aquarium food court, in other words, is most unlike doing it anywhere else.

Courtesy of Georgia Aquarium

The first public aquarium was the Aquatic Vivarium in Regent’s Park, London, which opened in 1853. A decade earlier, the very form of the aquarium, defined as a glass tank filled with water and containing marine plants and/or animals, did not exist. Nathaniel Bagshaw Ward, a British surgeon, had developed self-contained glass containers for ferns and other delicate plants in the 1830s, and they were soon mass-produced and sold as miniature hothouse gardens. It didn’t take long for him to fill these tanks with water and small fish, and along with the immense success of Philip Henry Gosse’s The Ocean(1844), and The Aquarium (1854)—books that popularized the idea of owning a miniature ocean—the British public was primed with enthusiasm for a new proximity to the creatures of the sea.2 Gosse and David William Mitchell, the council secretary of the Zoological Society of London, discussed the idea of building a fish house at Regent’s Park; by early 1852, construction of the facility was ordered, and the following year the Aquatic Vivarium opened to the public with more than 3,000 specimens on display, collected by Gosse from the south coast of Dorset.3 A lack of precedent made for problems with algae and aeration from the start, but on the whole the Aquatic Vivarium exhibited all the basic traits of the contemporary public aquarium: a building containing flora and fauna from fresh and saltwater habitats, kept alive through technical means in glass tanks for public study and entertainment.

Public aquariums of increasing size, prestige, and technical capabilities would be built throughout the rest of the 19th century, each one hoping to overshadow the last. Not to be outdone, Paris opened an aquarium in the Jardin d’Acclimatation in 1860, featuring larger tanks, and more of them, than the fish house in London. The building was designed like a covered colonnade, resembling the popular shopping passages of central Paris at the time, with fish tanks in place of window storefronts. Unlike the glass Aquatic Vivarium, the interior of the Paris aquarium was kept dark, the hall lit only with the dappled light passing through the fish tanks. Early commentators such as Arthur Mangin, a celebrated naturalist, compared the aquarium to Louis Daguerre’s dioramas—purpose-built light theaters that similarly brought visitors into a darkened space, where views of often exotic, faraway places were projected onto translucent screens.4

The public aquarium arrived in the United States in 1857 when P.T. Barnum opened the Ocean and River Gardens at his American Museum in New York. It is well known that Barnum’s wheelhouse was flippant, even lewd entertainment, beginning with his traveling roadshows.5 In 1841 Barnum took over the foundering Scudder’s American Museum, located on Broadway, across from St. Paul’s Cathedral, and lit its entire five-story exterior with limelight. At a time of privately owned cabinets of curiosity, before the public museum, Barnum’s became the most well-known and visited of all such institutions in the country, showing paintings, wax figures, trinkets, and tools from around the globe. Barnum’s large performance hall presented lectures, music, diorama-like light shows, and plays. Education was inextricably mixed with entertainment in the exhibits and programs: trick mirrors were shown alongside optical instruments, stuffed toys alongside taxidermy and skeletons; also featured together were the “preserved hand and arm of the pirate Tom Trouble, a hat made of broom splints by a lunatic, and (a traditional Connecticut specialty) a wooden nutmeg.”6 At the time, displays like these were considered “rational” entertainment, in that they possessed scientific and cultural value. As international travel was not an option for most visitors, Barnum also provided 194 “cosmoramas,” devices through which visitors could observe illuminated vistas of exotic locations and world wonders.

Courtesy of Georgia Aquarium

Barnum, of course, was able to travel, and a visit to the Aqua-tic Vivarium in London inspired him to open an aquarium of his own. Assistants from Regent’s Park were recruited for his Aquarial Gardens, where sea stars, sponges, crabs, and anemones, sharks, porpoises, and brilliantly colored tropical fish were exhibited alongside miscellaneous booty from Barnum’s collecting trips.7 Concerts were held in the same space as a large circular tank, 30 feet in diameter and 8 feet high, which held alligators; similar ones held seals, and a rock pool held sea lions. Seawater from beyond Sandy Hook, New Jersey, was pumped in through rubber tubes hidden between rocks and marine decor and connected to life-support machines, all hidden from view. The biggest draw to the aquarium was its whale display, particularly because, as historian Bernd Brunner describes, “the task of bringing one in was, as one might guess, quite a challenge.”8 The animals were lured into in a deep bay close to the ocean during high tide and trapped there as it subsided; they were then “placed in wooden boxes that were stuffed with algae,” Brunner explains, “and transported into the city on special boats, wagons, and trains.”9

Performance theorist Judith Hamera has written about Barnum’s and other early American public aquariums as theaters, where animals (“characters”) were given proper names, for instance, and feedings were scheduled as shows.10 In The Aquarium, Gosse endows underwater denizens with the attributes of humans (or familiar land mammals), describing prawns as “pellucid ghosts,” and calling the shaggy-looking marine worm a “sea mouse.”11 There is, of course, a limit to our empathic relationship with fish: aquatic animals typically enter our lives as merchandise; we have no easy way to determine their sex or age. Hamera frames this relationship as a Brechtian one: we recognize ourselves and our world in theirs, yet their alien bodies and behavior prevent us from identifying fish as possessing any function of reciprocity. “Fish don’t return the gaze as mammals do, because they don’t have faces with the same orientation of features,” she writes, “making ‘face-to-face’ encounters with fish a category all its own.”12 This disparity gives viewers a measure of control: as with theater, they are observers on the other, darkened side of the wall, with no expectation to participate.13 Providing a framework for these theatrical trappings is the physical structure of the aquarium itself: it must offer a total environment, graspable in one, convenient vignette.

Courtesy of Georgia Aquarium

HOME DEPOT CULTURE

Marcus viewed the Georgia Aquarium as a gift, to his employees, and to Atlanta, his adopted hometown and the city in which he and his business partner, Arthur Blank, co-founded Home Depot in 1978.14 The company’s philanthropic programs began as soon as it was solvent; Blank, like Marcus, would also establish a foundation in his own name. Much of their joint corporate and independent charitable work takes place locally, although by the early 1990s, Marcus, who is Jewish, had become concerned with Israeli politics, and co-founded the Israel Democracy Institute in Jerusalem. As the story goes, Roy Barnes, then governor of Georgia, accompanied Marcus on a tour to Israel, and on the flight back, Marcus revealed that he wanted to offer Atlanta a gift. “I wanted to do something spectacular,” he said of his desired expression of gratitude to the city, “something that would last.”15 By the time the plane landed, Marcus had agreed to put the city on the cultural map by funding an aquarium in Atlanta.

The choice of an aquarium over a museum, opera house, or symphony hall reflects Marcus’ social views. “My employees, my associates—they are not really symphony people,” he explained. “But an aquarium—everybody loves an aquarium!”16 In an article on his philanthropic work, however, Marcus noted that he is not “a fish guy”—he would go to the aquariums, but to “watch the people as much as the fish.”17

This regard for “people” has defined Marcus’ personal, philanthropic, and business leadership style. In Inside Home Depot (1999), Chris Roush examines the fundamental values that determine much of how the company is run. In 1978, Marcus and Blank were both fired from Handy Dan Home Improvement, where they worked, respectively, as chief executive and vice president of finance. Marcus was 49 at the time, looking for a new job, as he describes it, without much money saved and with family to support.18 Marcus’ parents had emigrated from Russia, penniless, and in his view, it was their hard work, tzedakah (in Hebrew, a tradition of charity), and aspirational self-determination that made him who he was. (There is some poetry in the success of Home Depot, then, its founder having self-guided out of a hard situation, to create the epicenter of “do-it-yourself” culture.)

Ocean Voyager Built by The Home Depot promotional image

Within Home Depot company mentality, the importance of giving is reflected in employee training. It was ensured, at least through the late 1990s, that each Home Depot manager would have personally met either Marcus or Blank in training sessions. Marcus would give detailed lectures on how to engage customers—walking them to what they wanted, suggesting products that would improve their projects—and built a direct relationship with his staff in the process. According to Roush, no other comparable retailer offers training from top executives. This emphasis on pedagogy was passed on to the relationship between Home Depot salespeople and their customers—people, not mere consumers, intent on improving their homes, indeed their lives, through the store’s products and expertise. Daily, in-store home-improvement workshops took on a progressively proselytizing quality. In 1995 Home Depot published a popular 480-page book called Home Improvement 1-2-3, and launched a television program on the Discovery Channel called HouseSmart. Home Depot employees regularly appeared on the show as experts, who were thus at once empowered and made approachable, and allowed the retailer to reach 63 million homes with its message.19 Home Depot initiates came to internally refer to the company as the “bleeding orange”—a reference to the brand’s signature color, and its culture of engagement, self-empowerment, and “sharing.”

Of course, “doing it yourself” often requires help. Many of the company’s social initiatives are inspired by Marcus’ encounters with his staff. The Marcus Autism Center, for instance, a leading autism research center, opened in 1991 in Atlanta after Marcus met an employee with an autistic child. By 2012 the center had treated more than 15,000 children and young adults.20 Marcus is estimated to have a net worth of $3.8 billion. To date, he has given away a quarter of that amount to various charities.21 Marcus views his giving as social investments and requires accountability from grantees: “When I give $1 million away,” he explained, “I think about the sweat that I put into creating that $1 million. And I’m not going to be frivolous about it.”22 The Marcus Foundation not only scrutinizes organizations’ operations, looking for inefficiencies and ensuring there is competent leadership, but also expects them to adapt in response to the analysis, and to maintain the changes. Says journalist Andrew Ferguson, “Marcus’ immediate goal with any grantee is to infuse it with business-sense—make it run the way he ran Handy Dan and The Home Depot ….”23 The idea of this institution shaping others in its own image gives a new meaning to the brand of self-education and self-reliance engendered by Home Depot and its shoppers: the company helps its customers help themselves, yet its role as a provider of both knowledge and goods is never challenged by the customer’s newfound knowledge or sense of independence. The shopper’s perceived empowerment is perhaps more akin to a kind of corporate acculturation.

In the 1990s Home Depot donated money to more than 300 nonprofit organizations focused on at-risk youth, affordable housing, and the environment.24 It became a sponsor of Jimmy Carter’s Atlanta Project in 1991, giving a million dollars toward creating productive aid partnerships between big companies and the city’s low-income neighborhoods; adding to that were millions of dollars’ worth of home improvement products donated to the same neighborhoods in the subsequent years.25 Around this time, Home Depot hired Mark Eisen, its first manager of environmental marketing. Eisen aimed to replace environmentally harmful products in the stores with sustainable ones, started a buyback system that rewarded customers with cash for recycling through the store, and distributed a pamphlet called Environmental Greenprint, which taught shoppers how to avoid hidden toxins in household products, and compared the cost and environmental benefits of home repair.26 Concerns and command over one’s home environment became ecological. If part of the aim of Home Depot’s outreach programs is to connect its customers (and its ethos) to public life outside the area between the store and the home, the Georgia Aquarium is its loudest articulation of these goals.

Oceans Ballroom, Arctic Room, Classroom Style Setup, 2007 [courtesy of Georgia Aquarium]

A CONFLUENCE OF PURPOSES

The experience of the Brechtian theater of the Georgia Aquarium, offering us intimacy with the alien world of the oceans, is mediated by various agendas that seek to make themselves visible on this fluid stage. The aquarium’s mission, as stated in its first press release from 2005, is “to be an entertaining, educational and scientific institution featuring exhibitions and programs of the highest standards, offering engaging and entertaining visitors’ experiences, and promoting the conservation of aquatic biodiversity throughout the world.” Through an architectural analysis of the Georgia Aquarium, we see how these demands of entertainment, education, and conservation combine into a physical and measurable manifestation of a philanthropic gift, itself requiring a separate set of challenges to be met. At $250 million, the aquarium represents the single biggest gift the Marcus Foundation has given thus far. How the aquarium operates and how visitors experience it are shaped accordingly.

In 2001 Marcus; his wife, Billi; Frederick Slagle, director of the Marcus Foundation; and Benjamin T. White, their attorney, filed Georgia Aquarium Inc. as a tax-exempt nonprofit.27 In 2002 Marcus approached Jeff Swanagan to be the aquarium’s founding executive director and president; Swanagan had served as deputy director of Zoo Atlanta in the 1990s and spent four years as the CEO of the Florida Aquarium in Tampa, where he “saved” the institution from bankruptcy by shifting its focus from ecology and conservation to entertainment.28 A design competition was held, and the commission was granted to Thompson, Ventulett, Stainback & Associates, now tvsdesign (TVS), an architectural firm that has been prominent in Atlanta since the late 1960s. One of the first issues the architects pointed out were the design challenges of the site—which was not initially in downtown Atlanta, but in the newly redeveloped Atlantic Station. The Coca-Cola Company had amassed 20 acres of land downtown following the 1996 Olympics and related development in the area; when Marcus approached the soda giant, it changed its plans to develop a mixed-use complex there and donated nine of those acres to his aquarium.29

The World of Coca-Cola, a tourist destination with changing exhibits about the brand, opened next door in 2007, two years after the aquarium. True to form, Marcus was involved throughout the aquarium’s development. Early in the process, he observed that many aquariums had a linear design, like the one at the Jardin d’Acclimatation. For ease of circulation, that architecture encouraged visitors to move from one display to the next, and discouraged them from going “back” to revisit exhibits. This traditional design does not reflect Home Depot’s philosophy of self-determination; accordingly, TVS’ solution proposed to organize the aquarium according to what they called a “mall concept.” If the aquarium would not take the form of a Parisian shopping passage, it would still take its commercial spirit.30

Like spokes on a wheel, five galleries—Tropical Diver, Georgia Explorer, River Scout, Cold Water Quest, and the Ocean Voyager—were arranged around a central, triple-height atrium. Each gallery begins and ends at this central hub, allowing them to be visited in any order, and as many times as people like. The atrium ceiling is black and unlit, and giant white seashell-like disks appear to float before it, the intention being to give visitors a sense of being underwater. The atrium’s first floor is lined with the entrances to the galleries; its upper level is covered with curved bands that wrap around the space, and can be lit in different colors. Fluted full-height columns support multicolored spotlights that create a theatrical atmosphere. Also in the central atrium is the food court, and a set of wide spiral stairs that leads to the multimedia theater, a ballroom that can be rented for corporate events, and a children’s education center. The self-guided principle has its limits, however: naturally, the only exit is through the gift store.

Also important to Marcus was what he called the “wow-factor.”31 Before TVS was brought on, he had already hired the Goddard Group—an entertainment design firm known for its large-scale attractions at Universal Studios—to ensure that the aquarium experience was indeed “wow-inducing.” Through digital renderings and paintings, the firm’s CEO, Gary Goddard, presented Marcus with visuals of people walking toward a light at the end of a gangway through a vortex of water; transparent walls and floors packed with schools of fish, like shimmering, animated wallpaper and carpet; giant tubes of water with sharks overhead, piercing through walls like Atlanta’s downtown skyways; and a hall with a tank so big one couldn’t see its edges. One rendering—a view of the Ocean Voyager exhibit—depicted a whale shark arched up over a group of rays, all soaring above visitors huddled in groups, looking and pointing in wonderment.

Courtesy of Georgia Aquarium

One of the most immediate ways to impress a public is with sheer size, which the whale shark certainly delivers: “We wanted the biggest fish in the biggest tank with the biggest body of water, and the biggest window we could create for people to watch it all through.”32 Marcus, Swanagan, and ichthyologist Bruce Carlson—the aquarium’s second employee—had visited the Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium and were impressed by the 74-foot-by-27-foot acrylic window of the Kuroshio Sea tank. Okinawa had three young whale sharks—a species that had not been exhibited in North America.33 TVS received a wish list of species to accommodate, with whale sharks at the top. (Polar bears were on the initial list, too, but taken off due to the immense cost of their maintenance.34) Late in the process, it became clear that more funds were needed to realize exhibits of the desired scope. Marcus saw an opportunity for corporate partnerships, and the gallery names were adapted to reflect their new, exclusive presenters: Georgia-Pacific Cold Water Quest, Ocean Voyager Built by The Home Depot, Southern Company River Scout, Tropical Diver Presented by Southwest Airlines (formerly AirTran), and the SunTrust Georgia Explorer (now closed). In April 2011, as if in homage to Hamera’s theatrical metaphor, AT&T Dolphin Tales—a musical revue featuring live dolphins and a (human) baritone—welcomed its first audience. Coca-Cola had donated the land; UPS had shipped many of the animals, including the whale sharks from Taiwan and manta rays from South Africa. Deepo, an orange cartoon clown fish resembling Disney’s Nemo character, is the aquarium’s mascot.

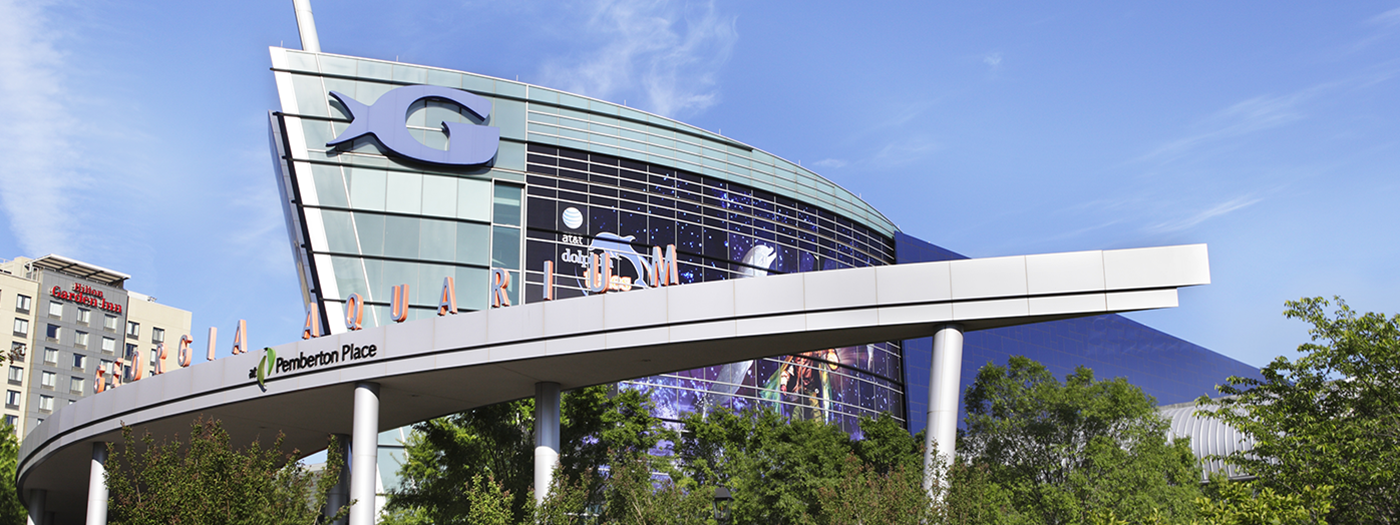

The Georgia Aquarium opened to the public on November 23, 2005, a little more than two years after planning began in earnest. Looking at the numbers, it is an unqualified success. It was an instigator for the development of Pemberton Place, as the area occupied by the aquarium, World of Coca-Cola, and most recently the Center for Civil and Human Rights, is now called (named for John Pemberton, Coca-Cola’s inventor). The half-million-square-foot building, containing 8 million gallons of fresh and saltwater and housing more than 120,000 individual animals of more than 500 species, has drawn more than 20 million visitors to the neighborhood—3.6 million in its opening year, and 2.1 million in 2013.35 And, in a tank filled with 6.3 million gallons of artificial seawater, through two feet of clear structural acrylic that is about 100 feet wide and three stories tall, the first American whale sharks can be viewed from a dark, ocean-blue hall, to the accompaniment of an orchestral score. The same gallery features a 100-foot transparent tunnel with a moving sidewalk to slowly move visitors through the tank, immersing them in the world of its reef sharks and manta rays. Since the aquarium’s arrival, downtown Atlanta has continued to grow: by the organization’s own account, it “spurred an ongoing revitalization of an entire neighborhood immediately adjacent to the Aquarium, the Luckie Marietta District, which now offers a charming and walkable streetscape featuring restaurants, bars, shops, loft apartments and condominiums.”36 As corporate investment returns to the area, Ernst & Young, the American Cancer Society, and others recently moved thousands of employees downtown. The aquarium itself employs roughly 300 full-time staff and an additional 300 part-time staff, plus 2,000 volunteers. As a nonprofit, the Georgia Aquarium opened without any debt, and it steadily earned money through ticket and concession sales, behind-the-scenes tours and special experiences, and ballroom rentals. The Marcus Foundation considers it a triumph.

As a place where the public gathers, and as a manifestation of Marcus’ multidimensional dream, the Georgia Aquarium constitutes a unique architectural experience where the goals of education, conservation, and entertainment emerge from directives of corporate entities and leaders, the requirements of urban renewal, and the basic needs of animal life of the world’s oceans themselves. As suggested by the toilet paper advertisement at the Georgia Pacific—sponsored beluga tank, every logistical step in the process of making an exhibit produces its own structural and analytical frameworks. Regardless of whether these systems are articulated to visitors, by their entering the aquarium, they become subject to those systems’ effects. To bring a pair of whale sharks from the coast of Taiwan to a new habitat in landlocked Atlanta took teams of marine biologists in both countries more than two years to organize. Accounts of the process are reminiscent of the spectacular capture and transportation of Barnum’s whales. Howard Krum, chief veterinarian at the Georgia Aquarium during transport, planned a meticulously detailed minute-by-minute schedule for the 8,000-mile trip. Interactions between the aquarium and the Taiwanese Minister of Fisheries required diplomatic management, as did international customs negotiations; medical protocol had to anticipate an array of potential mishaps, in addition to providing the advanced life-support technology needed to keep the animals alive.37 The final production cannot be dissociated from the politics of the many agents involved in its execution (to say nothing of the ethical implications of removing a wild animal from the wild, relocating it, and holding it in captivity for our viewing pleasure). Yet, just as they were in the 19th century, large public aquariums are closest in nature to screen-based media. Everything that happens behind that screen is flattened into a moving image to be consumed in toto. That two whale sharks died in Atlanta in 2007—but were quickly replaced, before a moratorium on their capture took effect in Taiwan a year later—is effectively eclipsed by the aquatic drama unfolding before our eyes.

In her philosophical essays about zoos and aquariums, Keekok Lee has written about the paradoxical concept of keeping “wild” animals in captivity. Can animals be both wild and captive? Keeping both conditions in play is one of the main objectives of zoos and aquariums.38 In Georgia, the aquarium galleries are not only branded, but the logos accompany names that celebrate individual conquest—Explorer, Voyager, Quest—in Home Depot’s language of self-empowerment. On display at the Georgia Aquarium, in the silent underwater world and its colossal natives, is a version of a Romantic sublime. The scene maintains our Western, late-capitalist views of humanity, individuality, and selfhood, defined as they so often are in contrast with conquered worlds and the enterprise advanced by their keepers. The containment of large, rarely seen beasts is, to the viewer, a dramatic display of our command over nature and evidence of an unconscious desire for that supremacy. In the context of the political, diplomatic, social, and financial relationships necessary for its establishment, the Georgia Aquarium is a spectacle of corporate command over the surfaceless immensity of multinational resources and supply chains—a spectacle we can appropriately term “the corporate sublime.

Carson Chan is an architecture writer and curator pursuing a PhD in architecture at Princeton University.

References

| ↑1 | The state-run website Georgia.org maintains a list of the biggest Fortune 500 companies that have their headquarters in the state. At the time of writing, Coca-Cola came in third. Home Depot came in first, with UPS in the second position. See Competitive Advantages. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Bernd Brunner, The Ocean at Home: An Illustrated History of the Aquarium (New York: Princeton Architecture Press, 2005), 39Ð40. |

| ↑3 | See “David William Mitchell’s Aquarium Ambitions”: www.parlouraquariums.org.uk/Pioneers/Mitchell/mitchell.html |

| ↑4 | Brunner, 103. |

| ↑5 | A.H. Saxon, “P.T. Barnum and the American Museum,” Wilson Quarterly 13, no. 4 (Autumn 1989): 133. |

| ↑6 | Ibid., 134. |

| ↑7 | For a full description, see the Barnum Museum Archive on The Lost Museum website, an online archive jointly organized by faculty and students from the Graduate Center, City University of New York, and the Center for History and New Media at George Mason University: www.lostmuseum.cuny.edu/home.html |

| ↑8 | Brunner, 116. |

| ↑9, ↑15, ↑16, ↑17 | Ibid. |

| ↑10 | Judith Hamera, Parlor Ponds: The Cultural Work of the American Home Aquarium, 1850Ð1970, (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2012), 30. |

| ↑11 | Brunner, 44. |

| ↑12 | Hamera, 129. |

| ↑13 | Ibid., 28. |

| ↑14 | Andrew Ferguson, “Building America: Meet Bernie Marcus, Winner of the 2012 William E. Simon Prize for Philanthropic Leadership,” Philanthropy, Fall 2012, www.philanthropyroundtable.org/topic/excellence_in_philanthropy/building_america |

| ↑18 | John A. Byrne, World Changers: 25 Entrepreneurs Who Changed Business as We Knew It, (New York: Portfolio/Penguin, 2011), 28. |

| ↑19 | Ibid., 108. |

| ↑20, ↑22 | Ferguson: 2012. |

| ↑21 | Glass Pockets, “Profiles: Bernie and Billi Marcus,” www.glasspockets.org/philanthropy-in-focus/eye-on-the-giving-pledge/profiles/marcus |

| ↑23 | Ferguson quotes Donald Mueller, the executive director of the Autism Center, who says that: “Bernie gives you a list of deliverables. You meet with his people. You come up with a business plan. You have goals by the year, by the month, by the week, and you’re expected to meet them.” Foundation accountants are in constant touch with the grantee, monitoring their finances and reminding them of deadlines. |

| ↑24 | Chris Roush, Inside Home Depot (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1999), 137. |

| ↑25 | Ibid., 144. |

| ↑26 | Ibid., 142. |

| ↑27 | United States Department of the Treasury, Internal Revenue Service, “Form 990-EZ.” Short Form Return of Organization Exempt From Income Tax (Georgia Aquarium Inc.) (June 30, 2001). |

| ↑28 | Margie Trax Page, “Geneva’s Aquarium Expert Dies,” Star Beacon, June 29, 2009. |

| ↑29 | Harvey K. Newman, “Race and the Tourist Bubble in Downtown Atlanta,” Urban Affairs Review 37, no. 3 (January 2002): 308. |

| ↑30 | Author interview with tvsdesign principal. |

| ↑31 | 31 |

| ↑32 | Georgia Aquarium: press release, 2005. |

| ↑33 | Before the exhibiting of animals was instituted as a state or public matter, shipping single animals from faraway places and transporting them from city to city was the work of private individuals. For a good overview of the development of zoos and aquariums in the United States, and a list of “firsts,” see Vernon N. Kisling, “Zoological Gardens of the United States,” in Zoo and Aquarium History: Ancient Animal Collections to Zoological Gardens, ed. Vernon N. Kisling Jr., (Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, 2001). |

| ↑34 | According to the tvsdesign principal interviewed, Marcus wanted the public to be surprised on the aquarium’s opening day. The staff and architects were asked not to disclose information about the project, and in the construction drawings, the whale shark and beluga tanks had code names: Ralf and Bob. |

| ↑35 | Georgia Aquarium. Annual Report. Atlanta: Georgia Aquarium, 2013. |

| ↑36 | Georgia Aquarium. “Georgia Aquarium’s Economic Impact on Downtown Atlanta,” press kit, Georgia Aquarium, 2014. |

| ↑37 | See Howard Krum, “When Whale Sharks Fly,” in The Rhino With Glue-On Shoes, eds. Lucy H. Spelman and Ted Y. Mashima (New York: Delta, 2008). From their holding pens in the ocean, the sharks, each weighing about a ton, were trained with buckets of shrimp, two months before the transfer, to swim into a stretcher. From these stretchers they were lifted into custom-built transport aquariums on the deck of a Chinese fishing boat. The boat brought them to Hualien Airport, where a heavy-lift prop plane would carry the animals to Taipei, to be loaded into UPS 747 cargo planes. From there, they flew to Anchorage to clear customs and refuel before heading to Atlanta. The animals had to be hoisted up four stories to get them into their tank. |

| ↑38 | See Keekok Lee, Zoos: A Philosophical Tour (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005). By discussing animals within humanistic philosophy, Lee points out the anthropocentric nature of their endeavor,and she poses many rarely asked ontological and epistemological questions surrounding the keeping of animals. |