Art of the Airport Tower

Share:

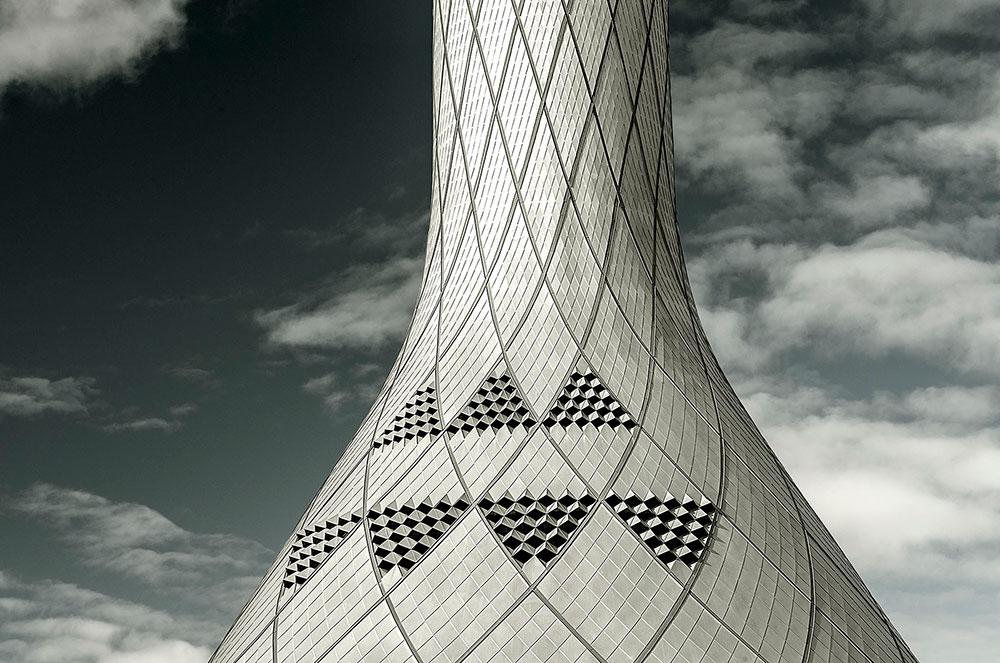

Carolyn Russo, Edinburgh Airport, Scotland, United Kingdom (EDI / EGPH) [courtesy National Air and Space Museum, Smithsonian Institution]

Casually and without elaboration, as if nothing strange or beautiful were implied, F. Robert van der Linden, curator of Air Transportation and Special Aircraft and Special Service Aircraft and chairman of the Aeronautics Department at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Air and Space Museum, writes in the Art of the Airport Tower exhibition catalogue that, as “the defining technology of the late 20th century,” flight has “liberated the world from the artificial constraints of time and distance.” This view of the planet as unexceptionally fluid and simultaneous—where temporal and spatial constraints are synthetic or, at least, a failure of human perception and ingenuity—suggests the mixture of physics, metaphysics, technology, and poetry that permeated the Art of the Airport Tower exhibition [November 11, 2015–November 30, 2016]. The show and its accompanying text are a romance and an instructive meditation on the complex phenomenon of air traffic control, and on the sites of its performance. Carolyn Russo’s photographs of contemporary and historical airport control towers offer an iconography of monoliths, in which concealed beings operate almost omnisciently within a pervasive infrastructure.

More than 14 million travelers fly on commercial airlines daily—or, as van der Linden puts it, 600,000 people are in the air every hour of the day—and each one is shepherded by the air traffic controllers who guide the flow of airplanes on the ground and in the airspace surrounding the airport. Air traffic controllers are the “lifeguards of the sky,” write Paul Rinaldi and Patricia Gilbert, president and executive vice president, respectively, of the National Air Traffic Controllers Association, “their workplace … a sanctuary, and the tower … a beacon; proof that no matter where you’re going, they will guide you there safely.” Passengers need only go along for the ride; neither their trust nor understanding is required. Something in the vatic language with which this sphere of operation is described conjures up St. Augustine and the concept of god as epistemic puppeteer, pulling the strings of an unwitting creation.

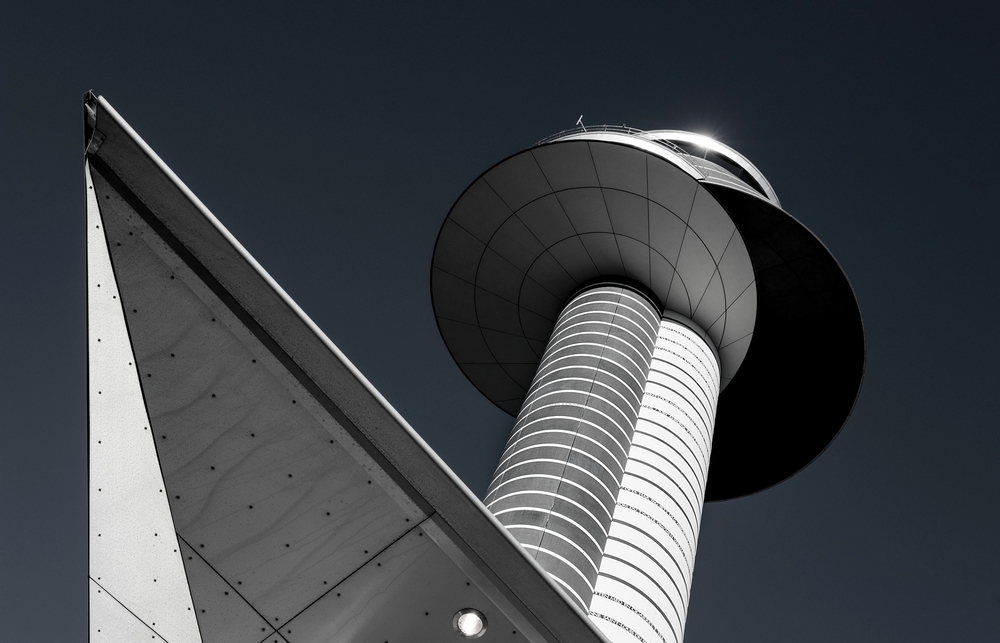

Carolyn Russo, Fort Worth Alliance Airport, Texas, United States (AFW / KAFW) [courtesy National Air and Space Museum, Smithsonian Institution]

Carolyn Russo, Edwards Air Force Base, California, United States (EDW / KEDW) [courtesy National Air and Space Museum, Smithsonian Institution]

The air traffic control tower remains, of necessity, an embodiment of the mantra “form follows function,” though Russo’s images pay homage to the sleek technological brilliance of contemporary towers, whose form has become increasingly imaginative and elegant. Whereas her photographs of decommissioned towers are rendered in a documentary, Düsseldorf School style, the working towers are detached from their surrounding landscapes, their geometries looming, often diagonally, against the flat background of the sky. The tower at BHX/EGBB in Birmingham, UK, is pictured as a juxtaposition of the squares of a gray-scale value system against the palest tint of blue. The coloration of the photographs is chalky and otherworldly, with occasional muted blues and rusty reds against deep, dark backgrounds.

The purity of the photographs’ composition is coupled with an idea of serene homecoming—“efficient bookends for each traveler’s journey,” Rinaldi and Gilbert write of the towers, conjuring up the cozy expanse of domestic space and travel of mind more than body. Art of the Airport Tower couples an ancient, Homeric notion of nostos with a utopian, even futurist vision of seamless mobility. Control towers are modern sites of the sublime, points of access to invisible forces in harmonious, inexorable motion; air traffic controllers are shamans or priests in the temples of the air. In her catalogue essay, Russo writes of the “powerful symbolic presence,” omniscience, and intelligence of these structures for “keeping humans safe.” Although the texts for the exhibition and book acknowledge the dangers, failures, and demands of air traffic control, they do so lightly and primarily in the context of justifiable praise for its effectiveness—the result, overall, is a peculiar (but compelling) tethering of the infrastructure of air transportation to the metaphysical.

Carolyn Russo, Stockholm-Arlanda Airport, Sweden (ARN:ESSA) [courtesy National Air and Space Museum, Smithsonian Institution]

A line of visitors waited outside the National Air and Space Museum when I visited on Thanksgiving weekend, and the galleries were jammed with people. They gazed up at the Boeings, Fokkers, Lockheeds, Spitfires, satellites, and Tomahawk cruise missiles; they crawled through the Airbus A320 Simulated Cockpit and bought tickets for the flight simulators, the space shuttle, and the Cosmic Coaster, which promises a “dazzling journey through the cosmos filled with futuristic imagery and non-stop fun.” Four drones—“military unmanned aerial vehicles,” as the visitor’s guide calls them—hung along the rail of the walkway above the West Gallery, the open space at the end of the museum’s expansive first floor where Art of the Airport Tower was installed, attracting a row of spectators three deep. Yet few visitors stopped to consider Russo’s exquisite photographs, with their implications of another, similar technological marvel: absolute safety, of a global higher power.

The astute sequencing in both the book and the exhibition took into account repetitions of pattern, shape, value, and texture particular to each tower, giving their presentation a syntactical logic. One wall at the National Air and Space Museum included a series of photographs of towers diminishing upward toward a single vanishing point, each topped by a circular observation cabin, like a series of mechanical flowers eyed from the ground up. Another sequence emphasized the frameworks around some towers: a space-age webbing, curling around the spires like geometric vines.

Carolyn Russo, Dubai World Central-Al Maktoum International Airport, UAE (DWC / OMDW) [courtesy National Air and Space Museum, Smithsonian Institution]

Poetry overrides technology in Art of the Airport Tower. The book contains concise factual, but also anecdotal, histories of the towers, which are identified by their three-letter International Air Transport Association airport codes and four-letter International Civil Aviation Organization codes. Russo makes all kinds of idiosyncratic associations in her personal identifications with the portraiture of each tower: Paris-Orly (ORY/LFPO) is a badminton birdie, and JFK/KJFK, a swan; Oslo (OSL/ENGM) is a human spine, and Abu Dhabi (AUH/OMAA), “flowing robes rising up from the desert.” While the images certainly conjure many objects familiar to art and literary theoretical vocabularies—the phallus, Barthelme’s glass mountain—the texts of Art of the Airport Tower make no allusions to any such tropes. Still, literary associations gather as silently and prolifically as the invisible instructions flowing through the white noise of airport traffic control itself: Satan’s Pandemonium and the Tower of Babel in Milton’s Paradise Lost; the tower as a symbol of “mysterious wisdom won by toil” in Yeats’ The Phases of the Moon; the signs of evil surveillance in Tolkien’s The Two Towers; the screaming void created by the absent towers in DeLillo’s Falling Man. The tower functions metaphorically as a site of isolation, labor, watchfulness, control, vanity, hierarchy, and/or knowledge, and these irresistible mythologies confer an epic quality upon Russo’s depictions.

For travelers moving within the sprawling web of the airport landscape, the airport tower is merely one, often invisible aspect of a labyrinth of ramps, carts, runways, terminal corridors, moving walkways, trucks, tugs, signage, checkpoints, and myriad other mechanistic and semiotic elements. For some, these spaces are fatiguing and byzantine, the vast but constraining airport landscape offering travelers the anxiety of Chris Marker’s La Jetée (1962), with its darkly atmospheric opening stills of the terminals and towers at Orly, rather than the godly and unpeopled calm of Russo’s control towers.

Airport Landscape: Urban Ecologies in the Aerial Age, an exhibition and conference that took place at Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design in 2013 (with a book forthcoming in 2016), offered a more critical investigation of the complicated and not always beautiful or effective functions of the airport complex. The exhibition included the plans of landscape architects working to envision a more humane and ecologically viable airport system, as well as Yann Arthus-Bertrand’s gritty Tarmac (2007)—images of runway skid marks taken from a moving helicopter, which read like the gestures of anguish in an Anselm Kiefer painting—and Phil Underdown’s Grassland (2005–2009), forlorn images of an abandoned airfield that testify to the irredeemable waste often built into human infrastructures. An Te Liu’s reinscription of signage and illuminated distance markers with Freudian terminology (Eros, Id, and Super/Ego, for example) provided direction as psychologically inexplicable to the layman as the coding on the tarmac is. By comparison to the Harvard project, Art of the Airport Tower offers a very reassuring view of aviation infrastructure, and an idealistic image of the all-embracing reach of air traffic control.

Interestingly, Russo’s images of working towers may soon become historical: augmented reality and virtual towers known as Remote Airport Traffic Control Centers (RAiCe) will displace the manned, on-site towers upon which we currently rely. Our reliance on air traffic control—manned or unmanned, on-site or virtual—still comes close an explicit contemporary faith. At 35,000 feet into the atmospheric blue, collapsing the constraints of time and distance, its pervasive and knowing power tugs us inexorably homeward.