Architecture and Sufficiency:

A Case Study in Applied History

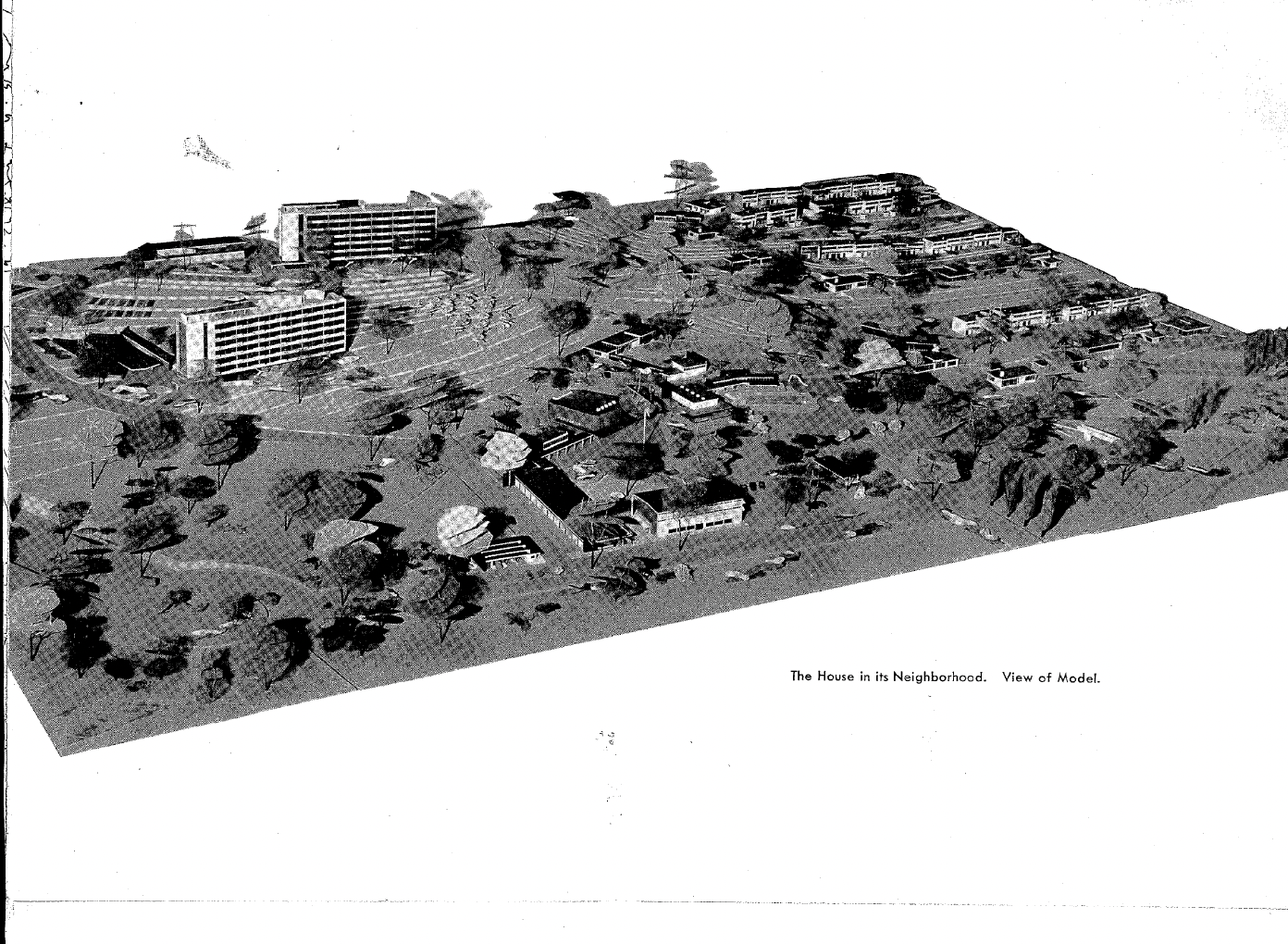

Serge Chermayeff, Vernon DeMars, and Susan Wasson-Tucker, “The House in the Neighbourhood” originally published in Tomorrow’s Small House, 1945 [courtesy of The Museum of Modern Art]

Share:

The Sufficiency Imperative

The April 2022 report Mitigation of Climate Change from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change offers a compelling contemporary lens through which to look back at the history of “sustainable” architecture. The term sustainability emerged into policy discourse with the 1987 Brundtland Report “Our Common Future,” and expanded during the Earth Summit in 1992 and afterward. Architectural discussions have had uneven engagement with the sustainable development discourse, despite the more or less simultaneous emergence of so-called sustainable architecture (perhaps marked by Foster and Partners’ HSBC building in Hong Kong, completed in 1985 though other contemporaneous examples would also serve).1

Sustainable architecture has been focused, over these last 40 years, on performance and efficiency: Architects aim to deliver a recognizable product, albeit with a more efficient mode of operation. Thus, the typologies of sustainable design—hyper-efficient curtain–walled towers, tightly sealed and air-conditioned bespoke luxury housing, the complex programs and systems of institutional projects—are not categorically distinct from what we have to call “unsustainable” architecture. The distinction is in performance. A sustainable building performs better, albeit marginally or only under optimal conditions, but better nevertheless.

Reliant upon these performance assessments, sustainable architecture breeds an obsession with metrics that support claims for the relative carbon efficiency of a given project. That sustainability (and its metrics) has also been a marketing tool perhaps goes without saying. Most building projects today claim some piece of the sustainable tool kit, as the rhetoric, methods, and principles of the field of architecture are slowly in transition.2 Yet, since such practices emerged, carbon emissions have been inexorably on the rise. Sustainable architecture has not worked. Or it has, but the goal hasn’t been dramatic change to the socio-ecological condition, but rather to permission structures. From LEED checklists to celebratory exhibitions, sustainable architecture has provided a screen behind which business-as-usual design and development practices can proceed apace, with a marginal improvement to energy demands, and with little impact on the social fabric of the present or on collective prospects for a liveable future. As Yamina Saheb, one of the drafters of the Mitigation report, puts it in a related article, “The collective failure in significantly curbing emissions from buildings raises questions about whether the present approach to climate change mitigation policies is adequate and effective. Efficiency improvements, combined with the slow adoption of renewable energy and minor behavioural changes, are insufficient to deliver on the 1.5° Celsius target.”3

The “Buildings” chapter of the Mitigation report offers a potent albeit discomfiting revelation: “In most regions,” the “Technical Summary” indicates “historical improvements in efficiency have been approximately matched by growth in floor area per capita.” In “developed countries,” particularly, the size of dwellings has gone up while the number of people in households has decreased.4 This dynamic confirms that, until recently, embodied energy calculations have largely been left out of sustainable energy discussions. Embodied energy refers to the emissions produced in the making of a building, including the carbon cost of materials and the construction process, as distinct from the operational energy required while the building is in use. Studies indicate that advocates who suggest sustainable architecture has reduced emissions often ignore embodied carbon costs, even though it is a significant component of the emissions burden.5

Serge Chermayeff, Vernon DeMars, and Susan Wasson-Tucker, “The House in the Neighbourhood” originally published in Tomorrow’s Small House, 1945 [courtesy of The Museum of Modern Art]

More floor area per capita means not only more materials and construction activity but also more space to heat and cool, usually through increasingly efficient, though nonetheless carbon-intensive HVAC systems (i.e., operational energy). This spatial growth has occurred alongside an increase in appliances, televisions, computers, and other equipment that requires energy and produces waste heat, further increasing cooling demands.

The Mitigation report, facing this conundrum and its consequences, proposes another useful, though also discomfiting, distinction. Whereas “efficiency … is about continuous short-term marginal technological improvements,” by contrast “sufficiency is about long-term actions driven by non-technological solutions, which consume less energy in absolute terms.” As Saheb puts it, “sufficiency is a set of policy measure[s] and daily practices which avoid the demand for energy, material, land, water, and other natural resources, while delivering wellbeing within planetary boundaries.” Design, arguably, falls between the policy and the practices, and renegotiates both. Architecture in the era of sustainability needs to focus upon sufficiency.

The challenge is to shift the discussion of architecture’s climate engagement away from efficiency and toward thinking about how buildings can be part of a broader transformation in demand management. Others have productively and provocatively framed this debate according to building moratoria and a renewed emphasis upon embodied carbon costs.6 For this issue on counter ecologies and their historical valence, I’ll explore an episode in which sufficiency in embodied and operational energy aligned briefly with a particular logic of suburban development. The example, set just at the end of World War II, played out speculatively, through journals and exhibitions; it suggests how design can render as desirable living comfortably with less carbon emissions, through design methods themselves, and also through the cultivation of novel practices of habitation. This episode does so through the constrained, racialized, and inequitable conditions of the postwar American suburb, reflecting and allowing for explorations of the promise and the challenges of the sufficiency premise in our still-inequitable contemporary world.

An Applied History of Sufficiency

Before “sustainable” architecture focused upon efficiency measures and metrics, there were numerous methods for designing and living that reflected—along the way to engaging other social and material pressures—this sufficiency imperative. Indeed, throughout history architecture has operated, by necessity, according to a sufficiency imperative. From the end of World War II until the 1970s oil crises, numerous practitioners and institutions sought to articulate design methods and professional frameworks that considered possible emergent technologies as part of new ways of life, especially regarding energy and resource demands.

A brief pause to consider this dynamic on slightly different terms: Until very recently, much of the discussion around renewable energy has been concerned with how solar and wind, for example, will provide the same energy, with the same consistency, that fossil fuels have conditioned overindustrialized economies to expect. How can renewable energy meet these established needs? It can’t. At the same time, much of what is experienced as a need across such economies is better seen as a desire, however habituated or reified. Instead, the bar of energy demand needs to be lowered, through design and through changes to social habits and practices, so that such non-carbon-based sources of energy can meet it—especially in overcarbonized regions.

Architectures of sufficiency explore the field’s capacity to experiment in the design and technology mechanisms that can maximize the effectiveness of non-carbon energy sources, as well as in the initiatives that can cultivate and reward practices and lifestyles that reject decades of carbon-dependent conditioning. Such architectures allow us to recognize that the design methods of the fossil fuel era, now past, were historically contingent and methodologically unique. Once this period, c. 1953–2008, is bracketed off, one can return, albeit with a different outlook, to some of the research, design, and material explorations that occurred before those anomalous decades.

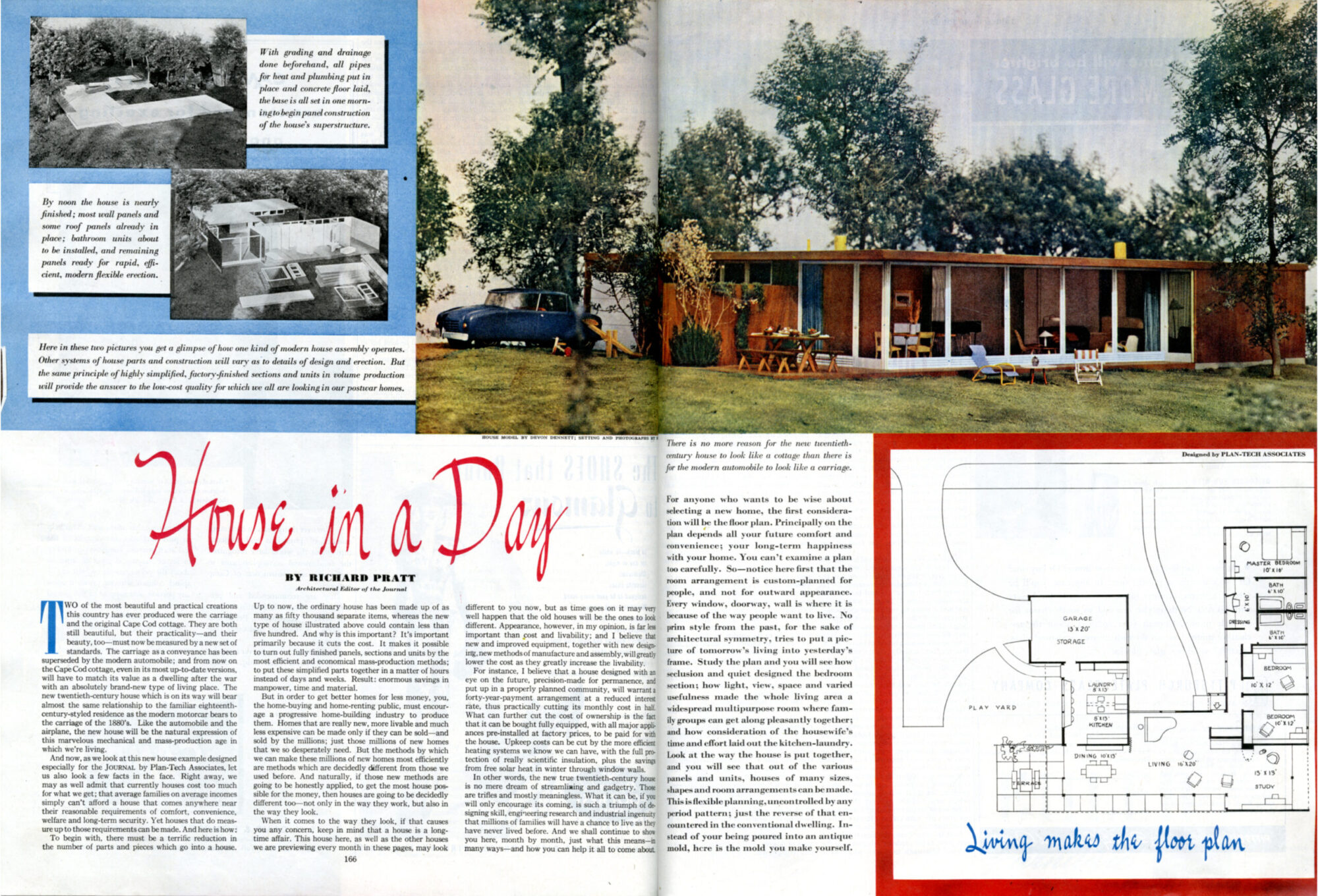

Richard Pratt and Plan-Tech Associates,“House in a Day” originally published in Ladies Home Journal, April 1945 [photo: Richard Pratt; courtesy of Meredith Corporation]

One potent example from this immediate postwar period is the 1945 exhibition and catalogue for Tomorrow’s Small House: Models and Plans at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. At stake was the provision of housing for returning soldiers in the expanding American suburbs, but doing so amid an extended moment when a general anxiety about future resource scarcity conditioned policies and practices. The Architectural Forum published an issue titled The New House 194x, which included numerous proposals focused upon flexibility and modularity—with clear suggestions of the sufficiency premise.7 Arts and Architecture, just after the war, published “What is a House?” with a diagram exploring financing and construction conditions that sought to reimagine the building industry—again, on terms recognizable to our current sufficiency imperative, though, of course, awash in details specific to the period.

These ambitions involved considering what, exactly, did a house need to be? How big? With what appliances and amenities? How could a good life be (literally) constructed, one that was sensitive to the economic and environmental externalities it might produce? During the war and just after—that is, before the geopolitical and geotechnical mechanisms for extracting oil from the Middle East and distributing it to the US and Europe had been consolidated—designers, writers, and others were asking charged questions about building and development, toying with design ambitions for demand management on contextually specific terms.8 At stake again today is how we can shake off the abundance mindset and see design as a means to facilitate a transition to sufficiency.

Tomorrow’s Small House was a 1945 exhibition organized by Elizabeth Mock, then curator for architecture at MoMA, and Richard Pratt, editor at Ladies’ Home Journal. They exhibited models of “small but really adequate houses [that could] dramatize the advantages of modern planning and building techniques” toward a new mode of living in the expanding suburbs.9 Pratt initiated the series in 1942, publishing an article on a traditionally designed “Victory House” to show the potential of a modestly sized, well-built, low-cost design for returning American soldiers and their families, to be located in the inner suburbs. By 1944 Pratt shifted focus to commission designs from Marcel Breuer, William Wurster, Edward Durell Stone, and others to offer these modern styles as “Houses Planned for Peace.” As Wurster recounted, and as is evident in Plan-Tech Associates’ proposal for a “House in a Day,” Pratt stipulated that the houses use off-site, modular construction and reflect the techniques, materials, and social pressures “inherent in this age in which we live.”10

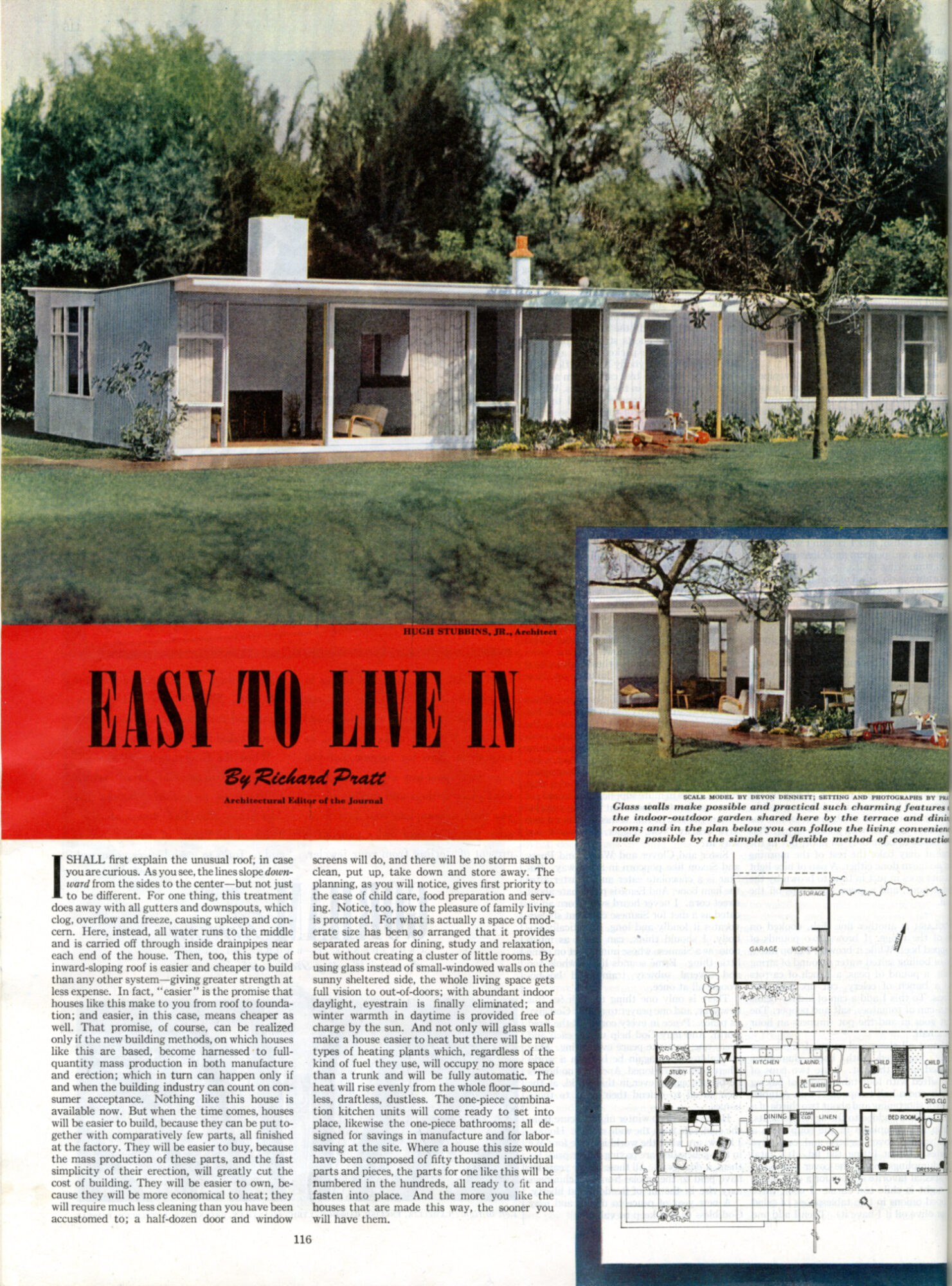

One such social pressure was energy scarcity, as America’s wartime demands had soaked up the reserves of domestically derived fossil fuels, and the global regime of petroleum distribution was not yet a well-oiled machine. One benefit of suburban lots was that the house could be oriented toward the sun. The basic principle of passive solar heating design involved, according to Mock, “a long, single–story, precisely outlined rectangle, open to the south and closed to the north.” This alignment was seen as an easy way to reduce demand amid ongoing energy uncertainty. As Mock states in the press release for the exhibition: “In almost every case the major rooms face south with great sheets of glass. The wide roof overhangs shade the interior in summer … but allow the sun to penetrate deep into the rooms in winter, when warmth is welcome.” This principle is touted in Hugh Stubbins Jr.’s Ladies’ Home Journal project as “Easy to Live In.” Mock went on to describe the technical novelty of insulated “triple sheets of glass” that provide some insulation to keep heat inside. “Such houses,” she concluded, here with reference to the wartime experiments of George Fred Keck, “have proven to be extraordinarily comfortable and economical, even in the extreme climate of Chicago.” Passive solar energy was seen as a straightforward way for the expanding suburbs to minimize energy needs, or at least to hedge against the uncertainty of America’s energy future, according to Mock, “the long, single-story precisely outlined rectangle, open to the south and closed to the north, will emerge as the dominant post-war plan type.”11

Richard Pratt and Hugh Stubbins Jr., “Easy to Live In” originally published in Ladies Home Journal, January 1945 [photo: Richard Pratt; courtesy of Meredith Corporation]

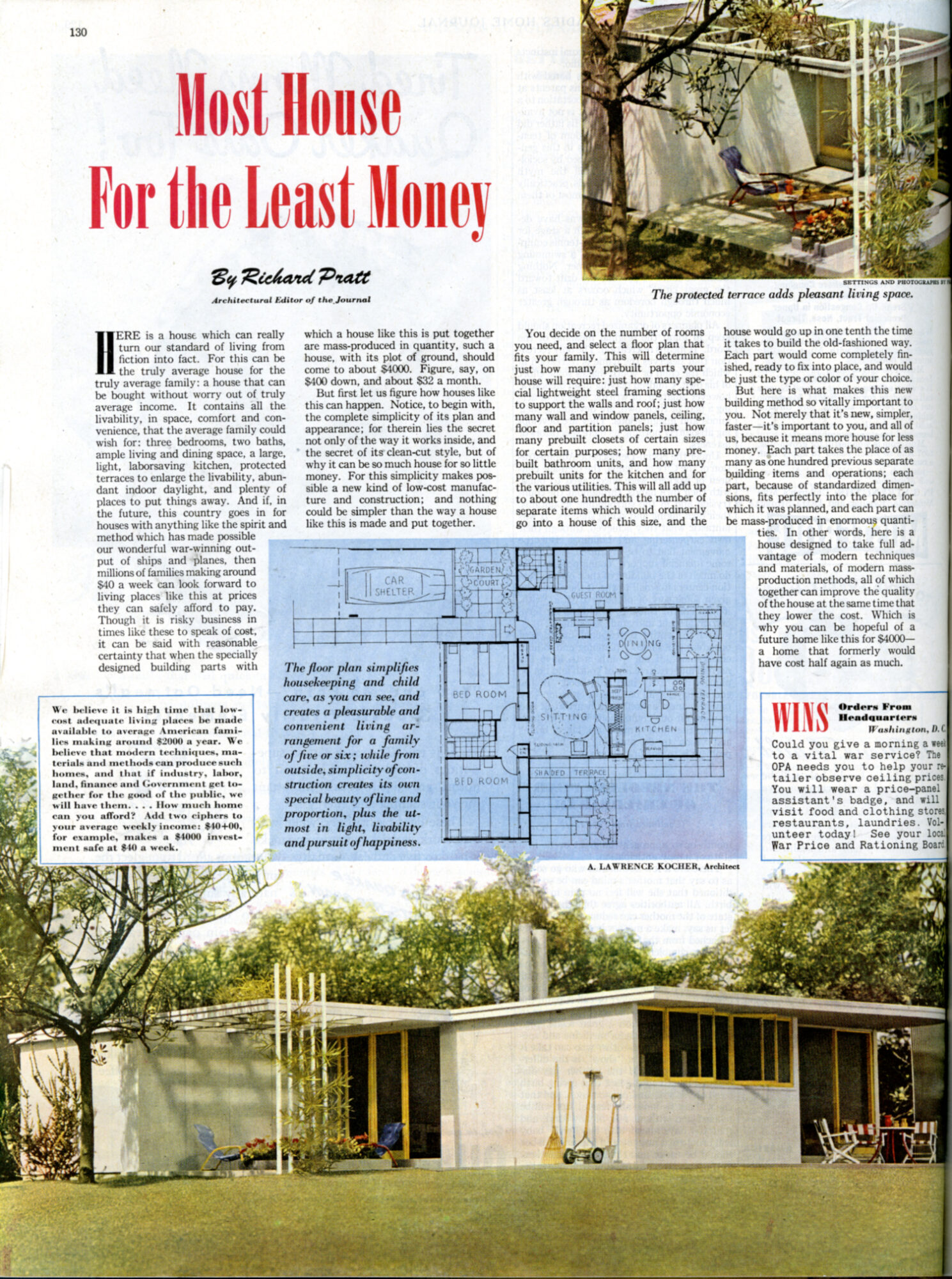

Richard Pratt and A. Lawrence Kocher, “Most House for the Least Money” originally published in Ladies Home Journal, November 1944 [photo: Richard Pratt; courtesy of Meredith Corporation]

Tomorrow’s Small House proposed a lifestyle and technical adjustment: compact, modular, and open to the sun. These houses offered a range of resonant benefits to the inhabitant and eased the work of expanding development farther away from the city. They were efficient in economic terms—low cost and variable —and sufficient in terms of floor area and energy demand. One example can be seen in A. Lawrence Kocher’s proposal for the “Most House for the Least Money.” Many plans included methods for expansion—adding a room as kids grew up, or as elderly parents moved in, as in Robert Hays Rosenberg’s “A House of Parts.” Philip Johnson’s project “As Simple as That,” emphasized that, in addition to the radiative benefits of sun, the small house on an open lot provided opportunities to live closely connected, visually and spatially, to the outdoors.

“The House in its Neighbourhood” was a community-oriented subdivision proposed in the Tomorrow’s Small House exhibition. The commissioned designs were arrayed across a gently sloping landscape and oriented to maximize solar exposure. The displayed model and drawings included multi-family dwellings designed by Vernon DeMars; and a restaurant, community center, and swimming pool designed by Serge Chermayeff. Susanne Wasson-Tucker developed the overall arrangement and interconnection of these elements.12

Tomorrow’s Small House aimed for sufficient ways of living—just enough, “really adequate”—that could respond to a future of anxiety and uncertainty. This aim was in sharp contrast to the design ambitions elicited by the energy profligacy of the fossil fuel era that followed. The included projects pitched sufficiency as an opportunity for a new way of life, with an almost gleeful embrace of spatial and temporal contingencies. An adequate house could grow, or shrink, as family size fluctuated. The projects expressed an openness to indoor/outdoor living and embodied a willingness to live in concert with daily and seasonal solar patterns. The envisioned occupants were, as a related document put it, “adventuresome enough” to weather the trials of solar living: opening and closing curtains, occupying different rooms in different seasons, operating vents and louvers as needed to minimize demand on energy structure.13 The sufficient life did not have to be one of scarcity but did require some adjustments.

This episode is just one in the architectural history of sufficiency. A parallel discussion could examine Frank Lloyd Wright’s Usonian houses, Hassan Fathy’s New Gourna project, or Jacques Michel and Felix Trombe’s solar houses in the Pyrenees—among the best known, almost canonical examples of many potential entries. The history of architecture and sufficiency suggests a porosity in the rigid distinctions that have characterized the field’s erstwhile attentions, which so often focus upon heroic figures engaged in the development of progressive design techniques. It turns instead to a chronologically heterogeneous array of climate and solar design strategies—regionally specific and culturally conditioned—that have emerged over a much longer period, and with less attention to formalist pedigrees, to consider design methods for life after fossil fuels.

Frank lloyd Wright, Weltzheimer/Johnson House in Oberlin OH, built 1949 [courtesy of Wikimedia Commons]

Equity comes to the fore because decarbonization through sufficiency is deeply embedded in ambitions toward decolonizing architectural discourse and practice. Sufficiency, as David Ness puts it, also requires solidarity. Given the fossil-fuel recklessness of so-called developed economies, sufficiency is, Ness explains, “primarily applicable to the Global North, where demand for new construction is questionable, while the Global South requires resources and construction to cater to burgeoning urbanisation.”

Within American suburbs, where “wants” have been framed as “needs,” and where the most dramatic shift is required to decrease carbon demand, the solar house represents a broader push toward sufficiency and an insistence that those who have most benefited from carbon wastefulness must reduce consumption most drastically. Such a shift does not have to be one of deprivation and want, but instead offers a design challenge rich with opportunity.

Sufficiency also applies to transportation, leisure, and consumption in general, and it indicates an urgent, though as yet seemingly unreasonable, expectation for social transformation. In the building industry, in particular—gorged on carbon, seemingly stuck in patterns of economic growth, burdened with the hyper-financialization of real estate—the sufficiency imperative may seem absurd.14 That such changes will come, by design or by default, suggests that architects focused upon sufficiency can begin to cultivate and amplify this capacity for transformation—especially, again, in the overindustrialized economies that are “already built.”15

An applied history of sufficiency also recovers the brilliance of customary and traditional practices by looking to those threads that flourished before the dominance of the fossil fuel economy and makes them available for re-examination. Many of those traditional practices have persisted. As researchers look to solar energy for space heating, or to designing with earthen materials, or to systems of natural ventilation (not to mention to circular economies and wider social transformations), many find a wealth of historical examples and a convergence between the computational prowess of the present and the persistence of the sufficiency premise. Buildings can be seen as dynamic energy systems—as devices that can be retooled toward sufficiency—rather than as static envelopes for wealth accumulation, allowing us to reconsider the value of architectural practice in the present. Doing so offers an approach less about technical and design interventions labeled “sustainable” and more about a multiplicity of creative interventions in sufficient living.

Daniel A. Barber is professor of architecture and Head of School at the University of Technology Sydney, and a Guggenheim Fellow. His research and teaching focus upon how the practice and pedagogy of architecture are changing to address climate emergency. His most recent book is Modern Architecture and Climate: Design before Air Conditioning (Princeton, 2020), which follows A House in the Sun: Modern Architecture and Solar Energy in the Cold War (Oxford, 2016); see also his widely read essay “After Comfort” (Log 47, 2019). Barber has co-edited the Accumulation series of e-flux Architecture since 2016.

References

| ↑1 | For a brilliant reading of the HSBC and its relative energy demands, see Alexandra Quantrill, “The Value of Enclosure and the Business of Banking,” in Grey Room no. 71 (2018): 116–137. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | For a critical history of these metrics, see Aleksandra Jaeschke, The Greening of America’s Building Codes: Promises and Paradoxes (Princeton Architectural Press, 2022). |

| ↑3 | Yamina Saheb, “COP26: Sufficiency Should be First” in Buildings and Cities (October 10, 2021). |

| ↑4 | M. Pathak, R. Slade, P.R. Shukla, J. Skea, R. Pichs-Madruga, D. Ürge-Vorsatz, “Technical Summary,” Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [P.R. Shukla, J. Skea, R. Slade, A. Al Khourdajie, R. van Diemen, D. McCollum, M. Pathak, S. Some, P. Vyas, R. Fradera, M. Belkacemi, A. Hasija, G. Lisboa, S. Luz, J. Malley, eds.] (Cambridge University Press: 2022), 71. |

| ↑5 | World Green Building Council, Bringing Embodied Carbon Upfront (September 2019); see also David Ness, “Towards Sufficiency and Solidarity: COP27 implications for construction and property,” Buildings and Cities 3 (1) 2022: 912–919. |

| ↑6 | Charlotte Malterre-Barthes and Zosia Dzierżawska, “Graphic novel: a global moratorium on new construction, ARCHITECTURE WITHOUT EXTRACTION” in The Architectural Review 18 November 2021. |

| ↑7 | “The New House 194x,” Architectural Forum 82, no. 9 (September 1942), 65–142; see also “New Building 194x,” Architectural Forum 83, no. 5 (May 1943), 65–174; the series was developed by editors Ruth Goodhue, Doris Grumbach, George Nelson, John Beinert, and Henry Wright; see also David Smiley, “Making the Modified Modern” in Brendan Moran and Annmarie Brennan, eds., Perspecta 32: Resurfacing Modernism (2001), 39–54 and Beatriz Colomina, Domesticity at War (MIT Press 2007). |

| ↑8 | This anxiety is discussed as a generative framework for American oil dominance, in my A House in the Sun: Modern Architecture and Solar Energy in the Cold War (Oxford University Press, 2016); some of the examples that follow are also mentioned in the book, though in a different context and with different valence. |

| ↑9 | Museum of Modern Art (Elizabeth Mock and Richard Pratt), Tomorrow’s Small House (Museum of Modern Art, 1945): 5; see also Catherine Bauer, “Cities in Flux,” The American Scholar 1 (Winter 1943), 70. |

| ↑10 | William Wurster recounting his discussion with Pratt in Greg Hise, “Building Design as Social Art: The Public Architecture of William Wurster, 1935–1950,” in Mark Treib ed., An Everyday Modernism: The Houses of William Wurster (University of California Press, 1995), 156. |

| ↑11 | Press Release for Tomorrow’s Small House, Museum of Modern Art archives, registrar’s folder for Tomorrow’s Small House: Models and Plans (Exhibition no. 289). |

| ↑12 | Tomorrow’s Small House, 19. See also Pratt, “Good Neighbors,” in Ladies’ Home Journal 62, no. 2 (February 1945), 150–151 and Jenny Tobias, “Elizabeth Mock at the Museum of Modern Art, 1938–1946” unpublished manuscript (2003), Museum of Modern Art archives, curatorial folder for Tomorrow’s Small House: Models and Plans (Exhibition no. 289). Wasson-Tucker also assisted in the development of the exhibition and was, at the time, acting curator of industrial design at MoMA. |

| ↑13 | James Hunter and John I. Yellott, “Program for an International Architectural Competition for a Solar House on the Theme of Living with the Sun,” International Solar Energy Society Archives, Arizona State University Solar Energy Collection, box 4, folder 26, 3–14: 5. |

| ↑14 | See Pascal van Griethuysen, “Bona Diagnosis, bona curatio: How property economics clarifies the degrowth debate,” Ecological Economics 84 (December 2012), 262–269. |

| ↑15 | See Andrea Klinge, Patrick Fontana, Eike Roswag-Klinge, and Matthias Richter, “Reducing the need for mechanical ventilation through the use of climate-responsive natural building materials—Results for the EU research project H-House and building practice” conference paper, Seventh International Conference on Building with Earth, 2016. |