Anastasia Samoylova: FloodZone

Site-specific installation of Anastasia Samoylova, Gator, 2017/2020, from the FloodZone series [photo: Will Lytch; courtesy of USF CAM]

Share:

A bicycle-helmeted boy, shoulders drawn in slightly, stands on a ramp at the entrance of a parking garage. He is standing in water that appears to be lapping at his ankles. Farther inside the garage the water becomes deeper and darker. The boy in the photograph Flooded Garage (2017) is Russian-American artist Anastasia Samoylova’s son, photographed as they explored their Miami Beach neighborhood following hurricane Irma.

At a panel discussion for her solo exhibition FloodZone at the University of South Florida Contemporary Art Museum, Samoylova says she didn’t take the hurricane seriously until hers was one of only three families in the building who hadn’t evacuated. As an immigrant who left behind a cold northern climate, Samoylova was impacted by South Florida’s weather and culture. Hurricane Irma marked a turning point in her work. Samoylova turned her lens on her new tropical home to produce a collection of work—also titled FloodZone—with a view of climate change and undeniable rising sea levels.

Samoylova’s work is decidedly not disaster photography. Rather, it depicts and even participates in a much more complex relationship between the natural world and human society. Photographs such as Eggs (2019) and Painted Roots (2017) show spaces in which, depending upon your view, one is intruding on the other. In the black and white photograph Painted Roots, a plant that has sprouted within the flashing of a flat-roofed building has grown large and sent roots down the building’s wall, bulging under a coat of white paint like veins under the skin. This image, and others it appears alongside—Samoylova’s photographs of eggs laid in steel beams, mold growing on walls, and an alligator floating in murky water—are aesthetically pleasing, but they are also scenes from a slow turf war. Numerous works in FloodZone depict a push-and-pull between the city’s encroachment on the surrounding Everglades, and that wilderness’ seeming attempt to reclaim the city.

Anastasia Samoylova, Flooded Garage, 2017, from the FloodZone series [courtesy of USF CAM]

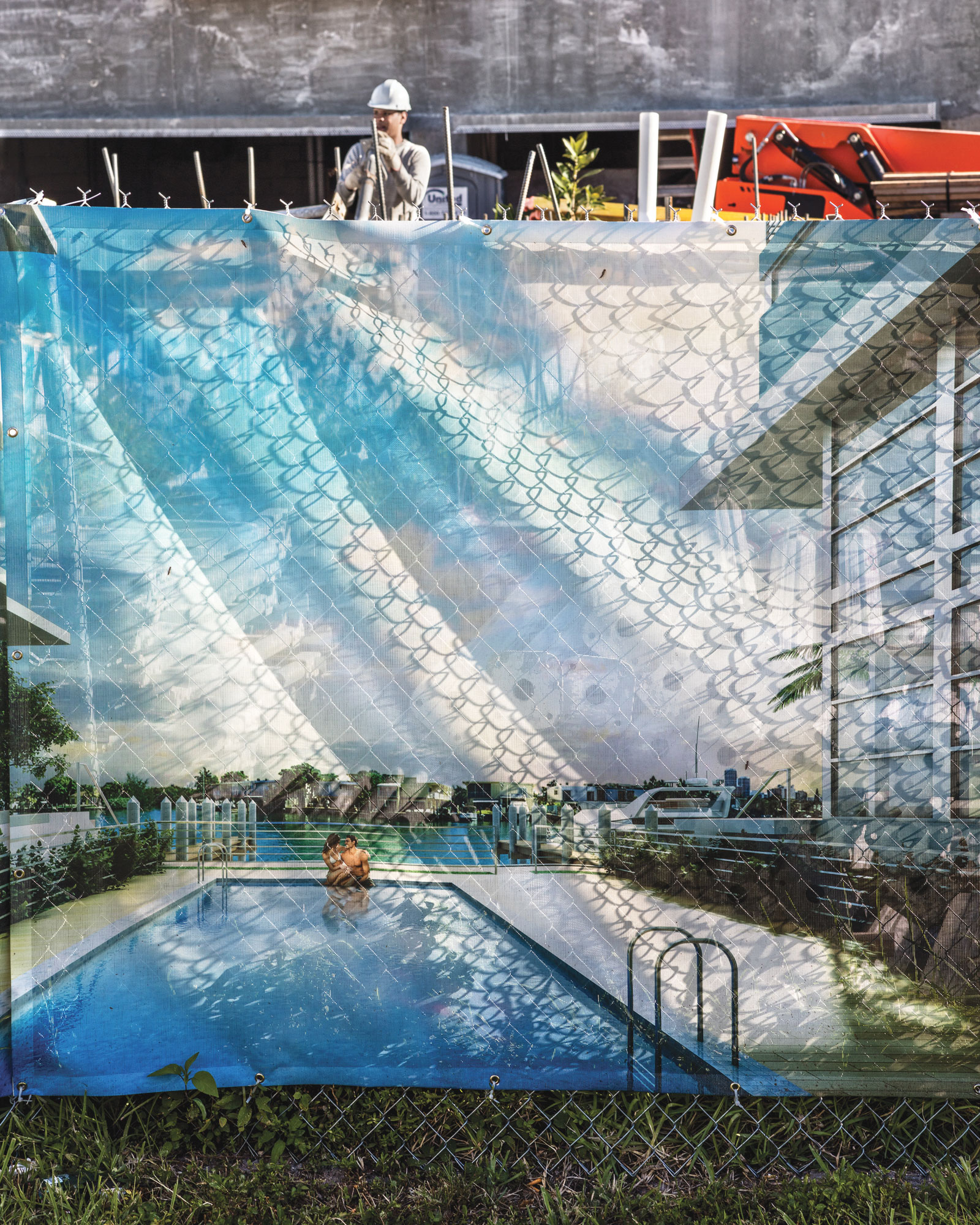

The most compelling aspect of FloodZone is how the exhibition juxtaposes genuine landscapes against highly idealized representations of landscape. Freestanding panels of six photographs stand at the center of the gallery, depicting what appear to be flawless views of Miami streets and glistening condominiums. Yet objects in each photograph, such as stray blades of grass or errant shadows, betray those flawless views to be just printed on decorative tarps, the type frequently used to hide construction sites. These tarps visually dominate the foreground of each photograph, which makes the actual setting difficult to discern, and the effect is disorienting. This effect is even more pronounced in such works as Camouflage (2017), wherein an idealized representation of the natural world is framed by its actuality. In the photograph, a pallet is wrapped in plastic printed with tropical trees. The photo-wrapped pallet has been placed in front of a chain-link fence, itself surrounded by subtropical trees. Although close physically and similar visually to the actual surrounding trees, the imagery of the plastic-wrapped pallet feels like an odd and perhaps malicious imposter. It’s also not trivial and perhaps ironic that the tropical trees are printed on what is probably a petroleum-based plastic. For Samoylova this scene typifies a Florida stretched taut between biome-in-peril and tourism-board-crafted paradise. In the context of the exhibition, works such as Camouflage question whether the state’s idealization contributes to its ruin in—as philosopher Timothy Morton calls it—an “act of sadistic admiration.”

Anastasia Samoylova, Square Lake, 2018, from the FloodZone series [courtesy of USF CAM]

Likewise, the photographs of FloodZone are aesthetically pleasing and Samoylova implicates herself as well as the viewer through the motif of reflection. The multilayered photograph Biscayne Bay Reflection (2018) shows a pane of glass with a lizard clinging to it, a bush behind it, and a sunset reflected in it. Most dominant though is the artist’s silhouette, caught in the center of the window’s reflection as she takes the photograph. It’s as if, in a series of works that touches so heavily on the connection between the glamorous depiction of a landscape and its destruction, Samoylova catches herself in the act of adding to the visual narrative of Florida-as-paradise. Notably, too, Samoylova’s silhouette mirrors the position of viewers as they stand in front of the photograph, likewise implicating us as image consumers.

Samoylova’s chosen medium of photography is noteworthy. To an extent it serves as a means to document a drowning state, capturing dry(ish) portions of Miami before waters and depths invariably smother the city. It is unsettling to think that this collection may operate as an archive of for posterity, in a time when FloodZone’s subject matter would represent a nostalgic and unreachable past. FloodZone emphasizes the brief liminality of the slow disaster of climate change. It responds to the need for visual testimonies while they are still possible, as each hurricane’s storm surge reaches a bit closer to the front door, but before it overtakes us entirely.