Against Closure: John Akomfrah and the Monumental

John Akomfrah, My Body Is The Monument, 2021, Giclee Print, Text, 40 x 60 inches [© Smoking Dogs Films. Courtesy Smoking Dogs Films and Lisson Gallery]

Share:

John Akomfrah’s practice can be considered in relation to the problematics of monuments, and it is apt to do so at a time of widespread decommissioning of statues depicting individuals long celebrated for their roles in dominant narratives of human progress. Doing so elaborates a critique of how monuments enforce fixed mythic values upon space and time. The monument “sits in a particular place and speaks in a symbolical tongue about the meaning or use of that place,” Rosalind Krauss has explained, referring to the statue of Marcus Aurelius on the Piazza del Campidoglio in Rome, which represents “by its symbolical presence the relationship between ancient, Imperial Rome and the seat of government of modern Renaissance Rome.”1 Thus, through its stately authority and presumption of permanence, the monument officiously sustains a singular narrative in favor of the power that erected it, and manifests that narrative as an unavoidable presence in its surrounding space. By the same token, as Achille Mbembe argued with regard to the 2015 removal of the Cecil Rhodes statue from the University of Cape Town campus, the toppling of colonial monuments destabilizes the myth of white supremacy they uphold.2

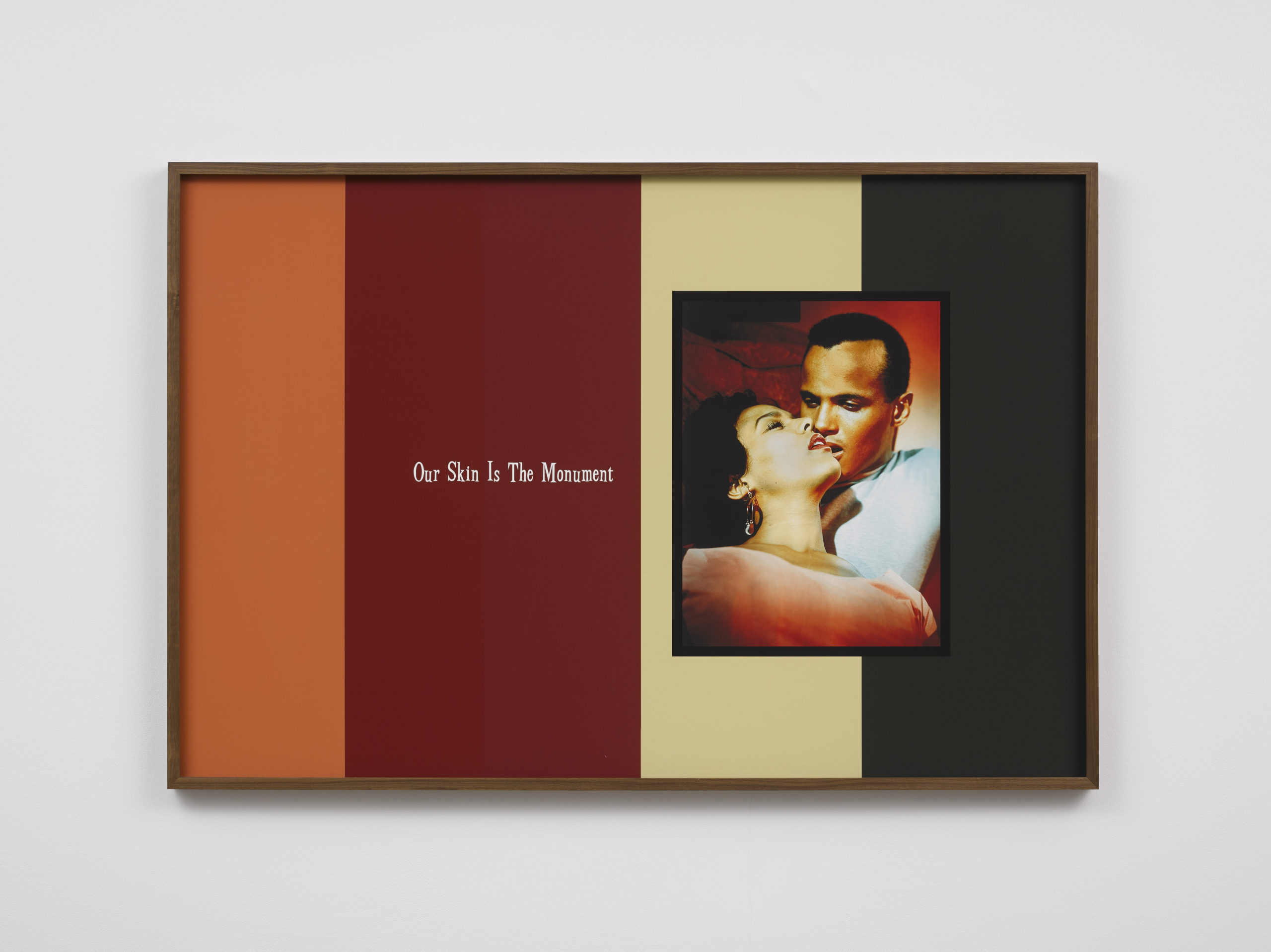

John Akomfrah, Our Skin Is The Monument, 2021, Giclee Print, Text, 40 x 60 inches [© Smoking Dogs Films. Courtesy Smoking Dogs Films and Lisson Gallery]

Perhaps Akomfrah’s works can be seen as anti-monumental because they stand for so much of what monuments suppress. His efforts to give voice to the silenced, to explode set-in-stone narratives, and to rethink the centrality of the human are all antithetical to the fixity, one-sidedness, and anthropocentrism of the monument. Indeed, the “thrilling ontological insecurity” (to use Kodwo Eshun’s words) elicited by Akomfrah’s bricolage technique bears an affective affinity to the ritualistic toppling of monuments.3 Thus it comes as no surprise that, in noteworthy instances of his work, a pronounced critique of the monumental frames his political aesthetic.

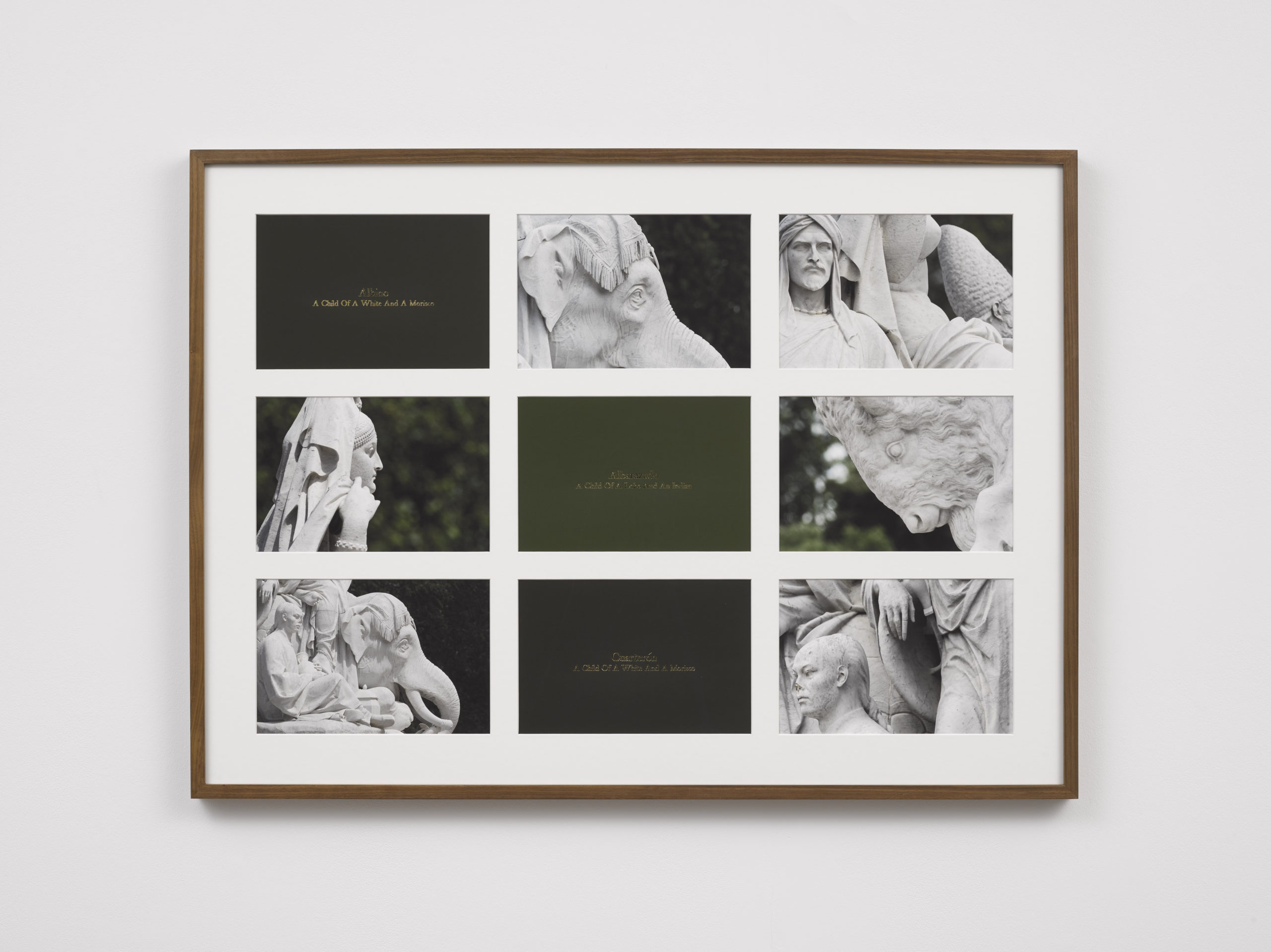

One might begin with two series of prints, recently exhibited at Lisson Gallery, London, that align monumentality with the hegemonic inscription of racialized meaning on the non-White body. In one series Akomfrah frames images of the Black actors Dorothy Dandridge and Harry Belafonte within a chromatic grid based upon the Shirley card, used in color photography to achieve skin-color balance according to a standard set by White models. Our Skin Is The Monument and My Body Is The Monument (both 2021), from this series, refer to Caroline Randall Williams’ 2020 essay supporting the removal of Confederate statues. Williams writes that her body, produced by generations of White men raping Black women in the American South, is a truer monument to the past.4 Her statement—and Akomfrah’s citation of it—are arguably anti-monumental in the way they shift attention from the stasis and immutability of statues to the fugitive quality of living bodies. Comparably, his series Monuments of Being (2021) consists partly of photographs of the allegorical continents—featuring ethnographic “types”—at the corners of the Albert Memorial in London’s Kensington Gardens, probably the city’s grandest monument to the British Empire. Each text accompanying Akomfrah’s images defines a racial classification (“Albarazado: A Child Of A Lobo And An Indian,” for example), thus highlighting the epistemic violence of race science that informs imperial propaganda.

John Akomfrah, “The Monuments of Being” Series No.Three, 2021, Giclee Print, Gold, Text, Framed: 35 3/8 x 48 3/8 x 1 5/8 inches [© Smoking Dogs Films. Courtesy Smoking Dogs Films and Lisson Gallery]

John Akomfrah, “The Monuments of Being” Series No.One, 2021, Giclee Print, Gold, Text, Framed: 35 3/8 x 48 3/8 x 1 5/8 inches [© Smoking Dogs Films. Courtesy Smoking Dogs Films and Lisson Gallery]

Such deconstruction of colonial monuments harks back to some of Akomfrah’s first films, made in the 1980s with the Black Audio Film Collective. In Signs of Empire (1983) and Images of Nationality (1984), for example, slides of colonial monuments, including the Albert Memorial, dissolve into images of the ultraviolent colonialist realities that they mask. Perhaps Akomfrah’s most explicit and comprehensive incorporation of anti-monumental discourse into his video work appears in Handsworth Songs (1986). The film’s subject—the 1985 riots that erupted in London and Birmingham, among mostly Black and Asian communities that had emigrated from former British colonies—demythologizes the fiction of multiracial harmony embodied in monuments such as the Albert Memorial.

Handsworth Songs opens on a life-size model of James Watt’s steam engine, guarded by a Black man in uniform. Soon afterward we see a statue of Watt himself. The engine reappears twice, halfway through the film and toward the end, as if its motion were somehow driving the social unrest. Now obsolete, the engine is purely commemorative, a monument to Watt—made explicit by his marble bust looming over it—and to the birth of modernity, all at once. It is disquieting that this function is maintained by Black labor, given the exclusion of Black suffering—which paid for so much of White “progress”—from the propagandistic telling of history that the monument represents. This discordance is made more pronounced by recent revelations of Watt’s activity in transatlantic slavery. After showing Watt’s statue, the film cuts to another, depicting the theologian and political thinker Joseph Priestley, whose support for the French Revolution triggered riots in Birmingham in 1791. This figure of liberty, however, who fought against slavery, is shown as an oppressor, the camera angle so low that he seems to stand on the viewer’s face. Clamor—shouts, bangs—can be heard in the background, then a police siren. One senses that despite Priestley’s abolitionist fervor in the 18th century, his statue distracts from the grievances of the present.

John Akomfrah, Handsworth Songs, 1986, Video still, Single channel 16mm colour film transferred to video, sound, 58 minutes 33 seconds [© Smoking Dogs Films. Courtesy Smoking Dogs Films and Lisson Gallery]

John Akomfrah, Handsworth Songs, 1986, Video still, Single channel 16mm colour film transferred to video, sound, 58 minutes 33 seconds [© Smoking Dogs Films. Courtesy Smoking Dogs Films and Lisson Gallery]

Many of Akomfrah’s works commemorate the dead, carrying out a function that monuments purport to do. Handsworth Songs is partly a commemoration of Cynthia Jarrett, whose death during a police search of her home triggered riots in London, and whose funeral procession appears in the film in vibrant, rebellious contrast to the affective deficiency of the monuments to Watt and Priestley. A reminder of Jarrett’s death is seen in Akomfrah’s recent Triptych (2020), which ends with three frames of memorials to Breonna Taylor, who was shot dead by police inside her Louisville, KY apartment in March 2020. These commemorations are not monumental. Rather than resurrect the dead to impose upon the living, they stage a scenario through which the living can grieve—can co-remember—the dead. Even Akomfrah’s most explicitly commemorative works—such as Seven Songs for Malcolm X (1993), At the Graveside of Tarkovsky (2012), Auto Da Fé (2016), Precarity (2017), and Mimesis: African Soldier (2018)—eschew the finitude of the monument (which might find its equivalent in a narrative biopic, for instance) to explore the variable and vulnerable ways their subjects are remembered, or could be remembered.

John Akomfrah, At the Graveside of Tarkovsky, 2012, Mixed media installation with sound and single channel HD colour video, Dimensions variable, 20 minutes [© Smoking Dogs Films. Courtesy Smoking Dogs Films and Lisson Gallery]

As a final example, At the Graveside of Tarkovsky is especially pertinent. It is exhibited as a multimedia installation with a cuboid block, suggestive of a monumental gravestone, that stands in front of the screen. If, in the block’s unavoidable presence, we identify the shade of Andrei Tarkovsky—the rejecter of finitude in filmmaking par excellence—such identification derives from Akomfrah’s montage of a bleak, otherworldly landscape, and from the haunting soundtrack by Trevor Mathison, not from the block itself. Rather than a materialization of Tarkovsky’s memory, the block is a fundamentally nameless object to which any memory can be affixed. As if to defy the deathly inertia of the block, the film and sound components of the work produce a mythopoetics that gives justice to Tarkovsky’s historical significance, and to his personal significance for the artist, without pretending to offer closure.

Tom Denman is a freelance writer based in London. He holds a PhD in Italian Studies from the University of Reading, for which he wrote his thesis on Caravaggio and the noble-intellectual community in seventeenth-century Naples. His art criticism has appeared in ART PAPERS, ArtReview, Art Monthly and Flash Art.

References

| ↑1 | Rosalind Krauss, “Sculpture in the Expanded Field,” October 8 (Spring 1979), 33. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Achille Mbembe, “Decolonizing Knowledge and the Question of the Archive,” lecture, Wits Institute of Social and Economic Research, University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, April 29, 2015. |

| ↑3 | Kodwo Eshun, “Drawing the Forms of Things Unknown,” in The Ghosts of Songs: The Film Art of the Black Audio Film Collective, eds. Kodwo Eshun and Anjalika Sagar (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2007), 75. |

| ↑4 | Caroline Randall Williams, “You Want a Confederate Monument? My Body Is a Confederate Monument,” New York Times, June 26, 2020. Online. |