A Body of Work

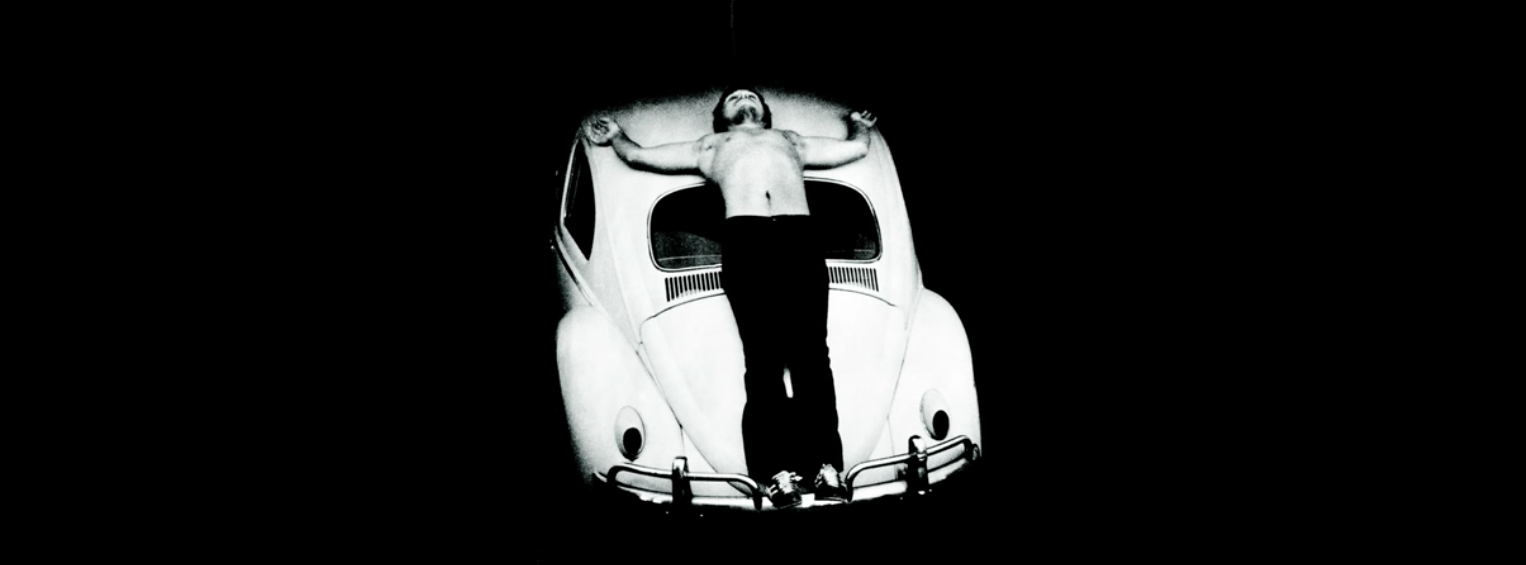

Youtube screenshot from “Chris Burden,” 2015 [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1px9ZCKfXuM]

Share:

Chris Burden died in May 2015. I’ve always been a fan of how he conflated the grandiose with the meek, producing a bathetic synthesis. Known in the 1970s for physically demanding performance works such as Shoot (1971) and Doomed (1975)—in which he arranged to be shot in the arm, and lay beneath under a precariously positioned piece of glass for 45 hours, respectively—by the 1980s he was making large-scale installations out of toys and other miniatures. Ultimately, he never abandoned the body. His performance, sculptural, and architectural works are united by their relationship to the conception of the body. Like the Microphones’ lyrics to “I Felt My Size” (“I’m small; I’m not a planet at all”) or Charles and Ray Eames’ Powers of 10, Burden’s works reflect upon orders of magnitude; they fixate on growth, and betray a fidgetiness with respect to it, not to be limited to contemplation of a plastic globe, or a restrained by the elementary school desk, during social studies.

I found out that Burden had passed away near the end of my shift as a nurse’s assistant in a St. Louis hospital. Christopher Knight’s obituary in the Los Angeles Times stated that Burden succumbed to a malignant melanoma.1 I’ve learned in nursing that a melanoma is a skin cancer of pigment-producing cells. In contrast to the mythopoeic, life-threatening performances of his youth, Chris Burden’s cause of death feels somehow prosaic. In a way, he died of corrupted color.

In the spirit of the transparency of Burden’s Full Financial Disclosure (1976), in which he disclosed his income and professional expenses in a “commercial” created for public access television, here are my class notes on melanomas:

- Melanomas, although composing 3% of all skin tumors, are the most metastatic of all skin tumors

- “black growth”

- melanoma mortality is 60% of all skin cancer death

- melanomas are strongly correlated with sun exposure

- genetic predisposition

- problems occur from allowing melanomas to metastasize

- melanoma can result anywhere in the body where there is pigmentation -you can have melanoma in your eyes (uveal)

- uveal melanomas can metastasize to the brain

- A—asymmetry

- B—border (are the edges of the growth rough looking as opposed to even and smooth?)

- C—color (melanomas are not uniform in color)

- D—diameter (is it getting bigger?)

- E—elevation (is it rising?)

I didn’t enter nursing school to write epitaphs to dead 1970s performance artists. Nursing is a good fit for those enamored of the art of looking, and I have some degrees and debts that allege I can look at certain phenomena with some degree of skill. As an art critic, I’ve spent a good portion of my post-academic life looking at art, putting it in the context of an artist’s professional successes and failures, academic background, checkbook, social-climbing ability, record collections, hobbies, sexual encounters, criminal activities, and television habits. I’ve come to understand that nurses make similar judgments about people and illness.

Every day, in a process fittingly called assessment, nurses intuit pathology by listening, touching, and looking for signs of disease. Through pattern recognition, nurses critique and evaluate breathing, examine neurological reflexes, and judge the efficacy of various medical therapies. The nurse develops a rich working catalogue of sores, sounds, smells, swellings, and speech. Whereas the art critic uses an affinity for visual culture in hopes of discerning an artwork from the phenomenon, the nurse differentiates the dysfunction from the individual. The art critic and the nurse can both be certain that phenomena may objectively have elements resembling art and illness respectively.

Upon finding objective criteria that speaks to a patient’s illness, the nurse’s mind redlines, thinking of the reasons this particular presentation may be indicative of a serious dysfunction and, if so, what next steps must be implemented to proceed with therapy. Within the first 60 seconds of patient encounter, the nurse thinks 48 hours in advance, often on behalf of multiple similarly sick individuals. The nurse’s use of language requires sobriety and directness, as well as thoroughness, mostly to prevent future litigation. Cultural critics masquerading as first responders, take note: the nurse has composed five review drafts in a matter of hours. One cannot play with words due to the urgency of getting a clear point across.

For anyone in the United States with a liberal (or fine) arts degree, the current job market is sobering. I spent 2010 trying not to get fired from my lucrative barista job, while applying alongside 300 other people for the five available humanities-related professions in St. Louis; I turned my basement into a pop-up space, and got wait-listed for the one graduate program I applied for. I began to have doubts about both my professional worth and grip on reality. The pile of unopened mail from my loan lenders suggested a “come to Prozac” moment could be helpful. My landlord, who was probably wondering if I’d be able to continue to pay the rent, told me to enroll in the certified nursing assistant (CNA) program at the community college. She, too, was in possession of a humanities degree from a private liberal arts college, but had found professional renewal working as a neuroscience nurse. I got my CNA license, started working on an orthopedic surgery floor, and realized that I liked working with people in this manner. I decided I wanted to go further, so I began to take prerequisite classes to enter nursing school.

- Clots form to heal injured blood vessels

- The coagulation process also includes a system to lyse the formed clot (Fibrinolysis)

- Fibrinolysis occurs when plasmin acts on fibrin

- Plasmin circulates in plasma as plasminogen

- When clotting is initiated, the fibrinolytic system is also set into motion

- Plasmin is fibrinolytic; fibrin is the last thing formed in the clot

- Sand castle analogy: if you build a sand castle and pour multiple streams of water through it

- Multiple canals lead to sand castle destruction

- This is how plasmin works on clots: canal creation

- The process by which plasmin removes the clot is called canalization (canal forming)

Nurses and art critics are both paid to employ a skill the liberal arts colleges call “critical thinking.” What I’ve found attractive about nursing is that in the clinical setting—a different white cube—my “critical” abilities actually have not only an authorial weight, but also an observable influence. Through the ostensibly “performative” role, to use the vocabulary of the creative vocations, of teaching patients about medications, DVT prophylaxis, and glucose management, I can use language to immediately “make a difference in someone’s life,” well beyond figures of speech. With art criticism, I’m lucky if someone apart from the artist informs me that my work was read at all. 2 Let’s be frank: the market, while great for art speculators and blue chip artists, sucks for most producers, and for all arts writers. The media-savvy entertainment spectacle of today’s art world has no room for criticism’s uncomfortable truths. Nursing, however, makes an art of mediating uncomfortable truths. A patient with awful pulmonary fibrosis who is looking for new lungs must be told that he’s not a candidate. The son (and the power of attorney) of the mechanically ventilated woman says he’s interested in quantity of life, not quality. A clinically hypoxic and cyanotic individual has refused supplemental oxygen in an attempt to bargain for narcotics. 3 As a nurse, it will be my job to patients and their families of medical realities they don’t want to hear. This requires the most delicate manipulation of phrasing and dynamics, and what’s usually most therapeutic is simply to correctly not speak.

I don’t understand why art critics are looking for new, embarrassing ways of existing as a professional species in the digital world. The Internet has empowered everyone to comment on cultural production; my peers want to work in that very world, translating western art history into emoji. If you identify as an art critic, but secretly want to be an artist and/or poet, then by all means, identify as such. Don’t confuse spontaneous web publishing for reasoned, compelling investigation into creative work if you just want to be in the art world. We are being disingenuous to art and artists if we aren’t aiming to be exhaustive in our assessments—in which case, criticism should be called journalism, reportage, or gossip, and no dosage of Google Cultural Institute, Monoskop, or UbuWeb will save it. Maybe when I can download a nuanced understanding of Ulysses, I will think otherwise, but for now I am a hermetic luddite who hates parties.

- Starling’s Law—the force of ventricular contraction is proportional to the length of muscle fibers. Therefore, when more blood enters the heart, more is pumped out. The healthy heart is able to precisely match output with venous return

- Because the heart’s muscles are a little bit different than skeletal muscles, the more you stretch the heart, the more force you get when the heart retracts

- No ATP (energy) is required for this recoil

- The slower the heart rate (a healthier heart), the more stretch you get

Studying the nurse’s role in the hospital has given me insight into the therapeutic potential of critique. I’ve always seen criticism as an empathic, creative act between opposing entities, with the critical text the synthesis of the communication. The critic can wear the artwork like a suit, and masquerade through the written word, making a show of acknowledging the artwork’s successes, failures, and longings as a matter of fact—and ideally, holding the mirror up to itself. The best critique allows the artwork to fulfill its maximum potential, to become its intention while judiciously holding it to its most minor claims. Such achievement can emerge only from the empathic drive of the critic, who literalizes and verifies the most bizarre and purple parts of the artist’s presentation only so that we might understand why they exist in a given work at all. I could be talking with a patient who denies any history of diabetes, yet whose blood glucose is somewhere around 400 and whose hemoglobin A1C is 7.6. No matter how much I humor the individual’s belief that he isn’t diabetic, the hyperglycemic crisis is real, and it is my job to see that it is resolved. As much as I want to find out why the patient believes what he or she does, I can’t ignore the more pressing medical issue. In order to look, whether at art or at illness, I must reset my vocabulary and build a new, encounter-specific model of the “real” against the spectral.

Having worked in the hospital for a few years, I can no longer dissociate my nursing work from my creative work. Looking deeply and precisely with therapeutic intention is completely concordant with artistic and critical practice (and I get to legitimately use practice). Although I don’t know whether capital-A “Art” can “heal” people, I’m certain that there’s something to being an artist or artistically minded that can be of benefit in the clinical setting. Opposite of bringing more people to the current marketplace of ideas and objects, the market and the art world could be entirely subverted by the argument that deep attention to one person can be art. If the true measure of art is the therapeutic benefit it brings, its value might even be able to be quantified. (Josef Beuys, the Artist Placement Group [APG], and Alan Kaprow thought about such means of production. The APG, for instance, advocated for a new, nonmonetary method of valuing art they called the Delta Unit.) 4

The promiscuity necessary to have a career fully devoted to “criticism” makes it impossible to entertain the idea of really falling in love with every artist and artwork encountered, or even to ascertain exactly what criteria, present or absent, are preventing the critic from doing so. Yet the empathic drive to criticize to which I have referred is modeled on a desire to love, to understand that which is not myself, and to admire or absorb it simply for the nature that it can be completely itself. I want to know everything about you because I love that we are rich in differences, even if we appear to be superficially similar. I want to hear all of your stories. I want to understand all of your constructions, your colors. I want to absorb your entire presentation. This is how art criticism, like nursing, is a form of emotional labor. 5

The magazine will pay me—modestly—to grant you my utmost attention. I’ll entertain your artist statement, and research your exhibitions and collected writings. In the hospital my patients don’t say to me, “Pretend I’m interesting and special,” but I will. I will clinically love you as if my license depended on it, even if I have to force it.

- CVA – cerebrovascular accidents aka STROKES

- Third most common cause of death in the USA

- Thrombosis

- Embolism

- Cerebral Hemorrhage

- Aneurysm with subsequent intracranial bleed (least common form of stroke)

- asymptomatic, i.e., the first symptom of an aneurysm is the funeral

- aneurysms rupture during increased activity

- “I felt something snap in my head, I felt something break in my head”

I don’t imagine that people in the art world or the marketplace of ideas take me seriously when I say that I’m becoming a nurse. I imagine that some feel it’s part of a grand conceptual gesture, and that I’ll bail once I’ve found the proper way of cashing in or legitimizing the working-class slog to aesthetes. Michael Brown’s murder last summer changed everything for a lot of us in St. Louis. The collected protests, marches, and agit-prop theater that emerged in response over the last 12 months are some of the best artistic interventions I’ve ever seen. Little can compare to the beauty and purpose of De Andrea Nichols’ collaborative sculpture Mirror Casket (2014), or prompt people with the urgency that DeRay Mckesson’s Twitter account does. Right now, the world of objects doesn’t need more of me in it. We have the power to affect a culture of healing outside the privileged art world. I can contribute to making a healthy people by giving attention and analytic abilities to my community.

My relationship to Chris Burden’s body of work is now mediated by both my study of art history and human pathophysiology. Is the latter essential to esteeming the former? No, but it contributes to my understanding of Burden, homo sapiens—that is, as a dude who walked, breathed, and may have been sensitive to the Los Angeles sunshine. I don’t pretend that this analysis is anything beyond a record of my own experience of sitting in a classroom, listening to a physiologist deliver information, which I have juxtaposed. I have thought about the health care workers, perhaps oblivious to his professional history, assessing Burden’s skin, and wonder about their remarks. What did they think when they examined the palms of his hands and left arm? Did they recognize the significance of these scars to a generation of artists and art workers? To this generation, the body is not just a body, but also a responsibility; an urgency toward understanding each work or patient’s unique history. Artists are people and people are artists, too.

William J. Gass is a writer and nursing student. He lives in St. Louis, MO.

References

| ↑1 | Christopher Knight, “Chris Burden dies at 69: artist’s light sculpture at LACMA is symbol of L.A.” Los Angeles Times, May 10, 2015: http://www.latimes.com/entertainment/arts/culture/la-et-chris-burden-dies-20150510-story.html#page=1. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | I plan on writing more about the (f)utility of professional art criticism after I finish nursing school, but watching some of the conversation about arts writing that took place at the Walker’s SuperScript conference in May 2015 has made me feel that some of my professional colleagues in the arts need to revisit what their definition of criticism is, not to mention their definitions of art and socialism. |

| ↑3 | The medical team decided to control this particular individual’s narcotic intake after discovering the patient “cheeked” pills, crushed them, and injected them into a peripheral IV. They still provided acetaminophen for pain management |

| ↑4 | Claire Bishop, Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship (London: Verso, 2012), 171. |

| ↑5 | Emotional labor is a concept developed by sociologist Arlie Russell Hochschild to describe the work done by flight attendants, nannies, and sex workers. These individuals are paid to emote with a host of clients. |