Thinking Through Contagion

Contagion, 2011, screenshot

Share:

On Tuesday, March 17, 2020, students enrolled in my Introduction to Film Studies course at Oxford College of Emory University were scheduled to study the topic “Narrative Form.” After my lecture there was to be, as always, a required screening that we would collectively discuss the following Thursday. Of the many surprises that have enlivened my teaching over the years, catastrophic coincidence was a decidedly novel twist. The film planned for that week was the 2011 pandemic thriller Contagion.

Our week on narrative form was finalized on a syllabus drafted the previous December. As news of an alarming new virus emerged over the course of the spring semester, I more than once made enthusiastic reference to the approach of Contagion on the horizon. On March 5, our last meeting before spring break, I bid the students a happy break and reminded them of the materials we would take up on returning to campus. Mention of the film was met with hoots of excitement. A teachable moment!

As I write these words, little more than a week after spring break began, COVID-19 has been declared a pandemic and a national emergency, the stock market has collapsed, grocery stores are empty, cultural events are canceled, people have begun to practice social distancing, and there is sharp panic in our new, potentially contagious air. Many universities—including Emory—have extended spring break an additional week following which all instruction is to be conducted online. Students have been told to gather their belongings from dorm rooms and head home; professors have been informed that clarification of what “remote learning” entails will be forthcoming. No one knows what happens next, but I know I won’t be teaching a movie that dramatizes the spread of a lethal virus that cripples the planet, inaugurated when a hapless bat sheds viral material into a pen of pigs destined to become entrées at an upscale restaurant in Macau.

Contagion, 2011, screenshot

I have maintained enthusiastic contact with Contagion for nearly a decade, avidly returning to it at least once a year since its 2011 release. It is one of the most compulsively watchable movies I know, propelled by an exacting formal intelligence that orchestrates multiple streams of action across a large ensemble of characters located on several continents. Like Zodiac (2007), another tour-de-force about an unfolding crisis, Contagion compels identification with a process: the key performance in a film replete with movie stars is the role played by the narrative design. The mosaic of micro-dramas that give shape to its story—a father trying to protect the lone surviving member of his family, scientists from the Centers for Disease Control and World Health Organization scrambling to crack the pandemic’s code, a smarmy blogger profiting off disinformation campaigns—are subsumed by a sense that what we are really watching are the operations of an impersonal mechanism, a pattern of information that includes human drama but is not reducible to the fate or feelings of individuals.

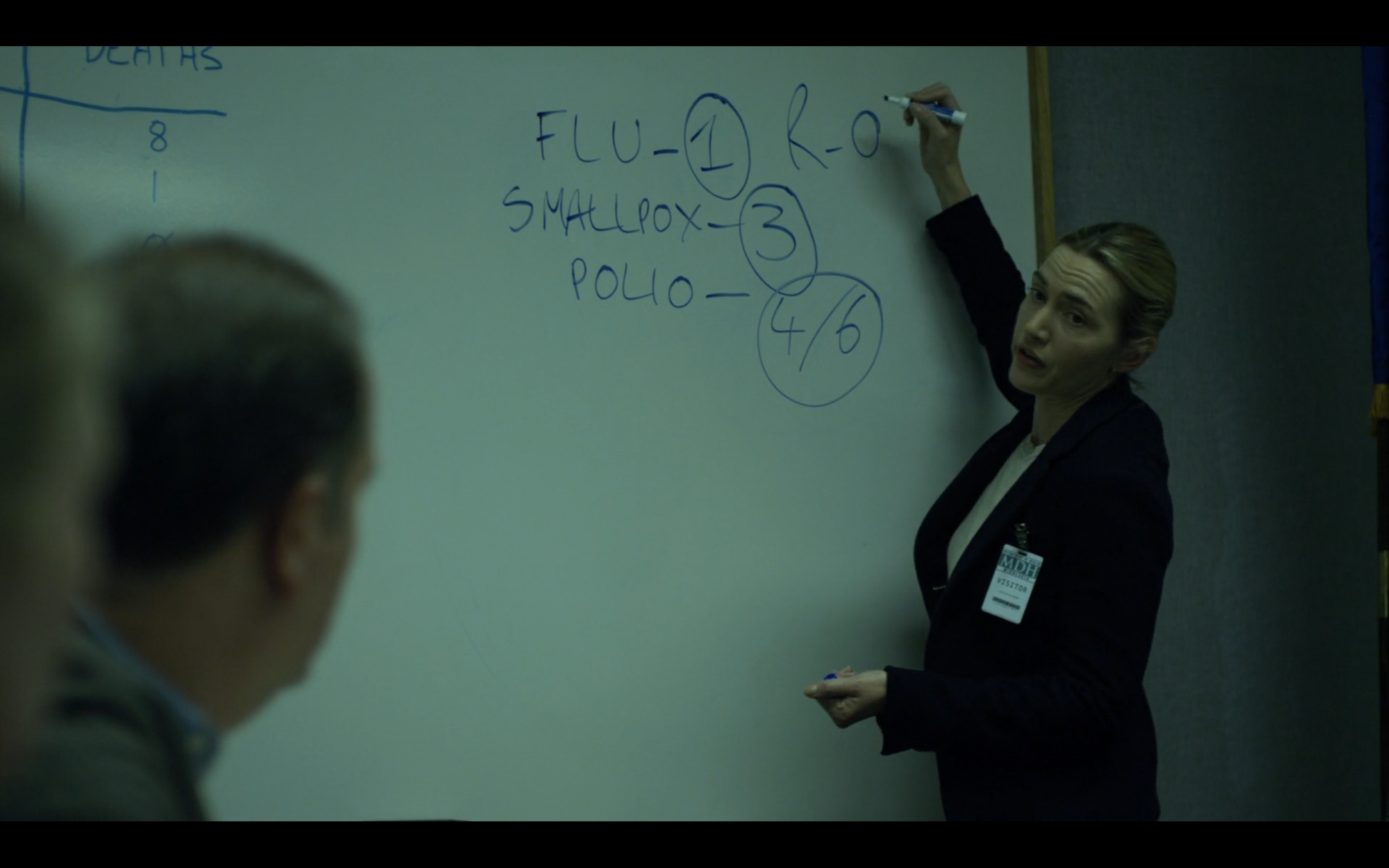

This cool, distanced ethos is exemplified by the subplot involving epidemiologist Dr. Erin Mears (Kate Winslet). One of several protagonists in the film who personify scientific rationalism, Mears rolls up her sleeves (without touching her face!) and gets to work, illustrating on a white board the concept of the “R-naught” value to dithering bureaucrats. Contagion commits to her didactic function in the narrative apparatus even as she contracts the virus. On waking up in her hotel room wracked with symptoms, she immediately calls the front desk to request the names and telephone numbers of every staff member she’s come into contact with. The pathos of Mears’ death sustains the relentless forward motion of this epidemiological principle. With the coldest of eyes, the movie observes her body unceremoniously dumped into a mass grave while her colleagues numbly discuss the shortage of available body bags. Harsh! But a point is being asserted: genuinely affecting and legitimately nerve-wracking, Contagion takes as its central object the analysis of information as such. It is the disaster film as treatise on the ethics of knowledge, a movie devoted to how we know what we know and how we act on that knowledge—to the extent that we have any.

Contagion, 2011, screenshot

The movie’s plot can be imagined as a diagram consisting of two superimposed planes. Expanding viral dissemination and the resulting social collapse take the shape of an implacably expanding spiral. Circumscribed by this temporal and spatial circuit, the second plane asserts itself as a set of oblique, discontinuous, thwarted, and converging vectors of problem solving. Each of these lines endeavors to outpace the perimeter of the pandemic spiral, to get one step ahead of its outermost curve: the trial and error process of vaccine experiments deep in the panic rooms of the CDC; the closing of borders and rationing of food; revised analytics and press conferences; institutional collaborations via video conferencing and individual survival on the streets.

Triggering as it is in the current moment, the return to Contagion does not lack pedagogical impact, albeit of an unsettling kind. It has been noted in the recent proliferation of commentary on the film that its saga of highly competent institutions swiftly kicking into action to coordinate a proficient technocratic global response may be the most implausible of the movie’s conceits. Much has also been made of the shady blogger Alan Krumwiede (Jude Law), perhaps the film’s least persuasive character but arguably its most prophetic, who trumpets his page views and rants about conspiracies while shilling a homeopathic formula dubbed “forsythia” that he claims has cured him of infection. Fact is truly stranger than fiction. Right-wing loudmouth Alex Jones was recently issued a cease-and-desist order by the New York state attorney general for claiming that his Superblue brand of fluoride-free toothpaste “kills the whole SARS-corona family at point-blank range.”

Contagion, 2011, screenshot

What continues to fascinate about Contagion and ensures its relevance beyond unnerving timeliness are not these topical resonances but rather the force of its aesthetic achievement. As the film critic J. Hoberman has noted, director Steven Soderbergh “is less a driven auteur or even an enthusiastic cinephile than he is a highly intelligent technician who sets himself a problem and goes about solving it.” In this light, Contagion is not so much a shrewdly made movie about a global pandemic than it is one that marshals the pandemic trope as the means to think through an array of formal challenges. How do you stage an event of this magnitude, signifying its reach and severity with maximum economy while avoiding overwrought spectacle or sentimentalism? How many protagonists are needed to articulate the dramatic scenario, and how do you pattern this weave of subplots for optimal clarity without resorting to schematic clichés of the genre? (Contagion notably lacks a structuring Bad Guy like Donald Sutherland’s militaristic zealot in the 1995 pandemic thriller Outbreak.) For a movie enthralled by analytics, data processing, planning, and implementation, how much information is too much information?

Contagion is a master class in how to pace and proportion cinematic elements; how to modulate and control a polyrhythmic narrative; how to balance the drama of human interest with an intellectual commitment to structural depersonalization. Every shot of the film has been calibrated for maximum efficiency and poised so that it can nimbly pivot to the next. The remarkable coda, which retrospectively discloses the etiology of the virus, consolidates the film’s dispassionate elegance so sharply you may get infected by the desire to watch it all again. An efficient thriller about smart people who move fast and work hard, Contagion is radiated by a steely cinematic intelligence. If the story imagines how a pandemic might emerge and entertains us with a compensatory fantasy of what the global response might look like, the film itself emblematizes the force of thought. When Contagion recedes as a cautionary tale, its lesson will endure: confront a problem and think it to death.

Nathan Lee is a Visiting Assistant Professor in the department of Film and Media Studies at Emory University.