The 2nd Helsinki Biennial’s Call to Action

Keiken, Ángel Yōkai Atā, installation detail, site-specific installation (architectural sculptural installation and sound, online mobile interactive experience, “Morphogenic Angels” controller game, video projection, and sound) 2023 [photo: Perttu Saksa; courtesy of the artist and HAM/Helsinki Biennial]

Share:

Curated by professor Joasia Krysa, the title of the Helsinki Biennial’s second edition, New Directions May Emerge, quoted anthropologist Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing’s 2015 book, The Mushroom at the End of the World. In the text, which approaches the matsutake mushroom as a prism through which to explore the symbiotic relationship between global trade, environmental degradation, and earthly evolution, Tsing describes contamination as a force of change and change as a matter of survival. In a world where “purity is not an option,” Tsing writes, contamination must be reframed as collaboration—that is, “working across difference.” Otherwise, “we all die.”

Exemplifying this call to find ways of living together is PHOSfate (2023), a collaborative project by Mohamed Sleiman Labat and Pekka Niskanen. Sandoponic pits growing kale, basil, coriander, potatoes, carrots, and lettuce were modeled after ones developed in Sahrawi refugee camps in Algeria, where the indigenous Sahrawi fled after Morocco’s 1975 invasion of Western Sahara. Through PHOSfate, Labat, who was born in a Sahrawi refugee camp, and Niskanen, who is Finnish, connect the dots between phosphate mining controlled by the Moroccan state in Western Sahara, and the eutrophication of the Baltic Sea due to excessive nutrients entering the water due to urbanization, food production, and agriculture.

PHOSfate, PHOSfate, installation view, 2023, [photo: Kirsi Halkola; courtesy of the artist and HAM/Helsinki Biennial]

In recent years, Finnish waters have undergone massive blooms of toxic algae made worse by climate warming. Yet, in keeping with Tsing’s reframing of contamination, some scientists saw an opportunity to collect specimens for research during one particularly significant cyanobacterial bloom in 2018—phytoplankton are crucial to the ecosystem, after all, producing half of the world’s oxygen. That alternate view, wherein crisis produces ambiguous opportunity, could likewise be applied to sandoponic gardening as an innovative form of sustainable food production, one developed out of a violent and ongoing displacement, which in turn frames these gardens as expressions of a very natural defiance: a will to survive.

Installed on Vallisaari Island, one of the main Biennial venues, PHOSfate emphasizes this biennial’s recalibration of catastrophe as a force for creation as much as destruction, which Vallisaari likewise embodies in the context of the Nordic-Baltic region’s geopolitical history. Imperial Russia used the island as a base during the Finnish War of 1808–1809 to besiege the neighboring island fortress of Suomenlinna, which was developed by the Swedes in the 18th century. Sanctuary, mist (2023), a site–specific installation by artist collective Remedies, conjured these historical specters. Every few minutes, a dramatic vapor cloud blew over an artificial pond created during the Russian occupation. The pond has become a flourishing habitat, due in part to the prohibition of swimming because of dangerous debris on its bed. That prohibition extends to the entire island. Much of the land is protected from human interference by fenced paths that protect visitors from left-behind explosives and unstable structures, making a history of human conquest intrinsic to Vallisaari’s current biodiversity.

Keiken, Ángel Yōkai Atā, installation view, 2023 [photo: Perttu Saksa; courtesy of the artist andHAM/Helsinki Biennial]

That dense historical entanglement between human actions and natural evolution expanded at the Helsinki Art Museum, the Biennial’s second main venue. Diana Policarpo’s multichannel installation Ciguatera (2022) was installed there, to great effect, inside a low-lit, blue-toned exhibition hall. Screens embedded into two large sculptures, made to mimic rock formations, tell the story of ciguatera, an illness caused by ingesting fish contaminated with toxins produced by a microscopic alga. In one two-channel video, we learn how the documentation of the disease goes back to Homer’s Odyssey, with reports by Vasco da Gama and James Cook pointing to the colonial history that intersects with a sickness which historically affected navigators and coastal communities. Some people saw ciguatera as “magic or miraculous due to the fact that it could resist and attack European traders,” the narration explains. Thus, they would “gift” contaminated fish, like Trojan Horses, to foreign arrivals.

Diana Policarpo, Ciguatera, installation view, 2022 [photo: Sonja Hyytiäinen; courtesy of the artist and HAM/Helsinki Biennial]

In another video, Policarpo trains the camera on the textures of Ilhas Selvagens, a Portuguese archipelago in the North Atlantic Ocean that is highly contaminated with ciguatoxins. Historically confined to tropical and subtropical regions, ciguatera outbreaks have increased in the Atlantic and the Mediterranean due to climate change, with infections in Europe often attributed to fish caught off Ilhas Selvagens. Ciguatera is composed as a reading of field notes by a researcher, stranded on the island, who has no choice but to eat contaminated fish. The narrator notes that the archipelago’s terrain is considered geologically analogous to that of Mars—so much so that an astronaut conducted training there. Another video characterizes the landscape’s otherworldliness by presenting a view of the archipelago from afar as it speaks with a human voice. The land asks “Who gets to decide what is detrimental to our nature if biology continuously turns misfortune to progress? … Bacteria and toxins, like all lifeforms, strive towards resilience.”

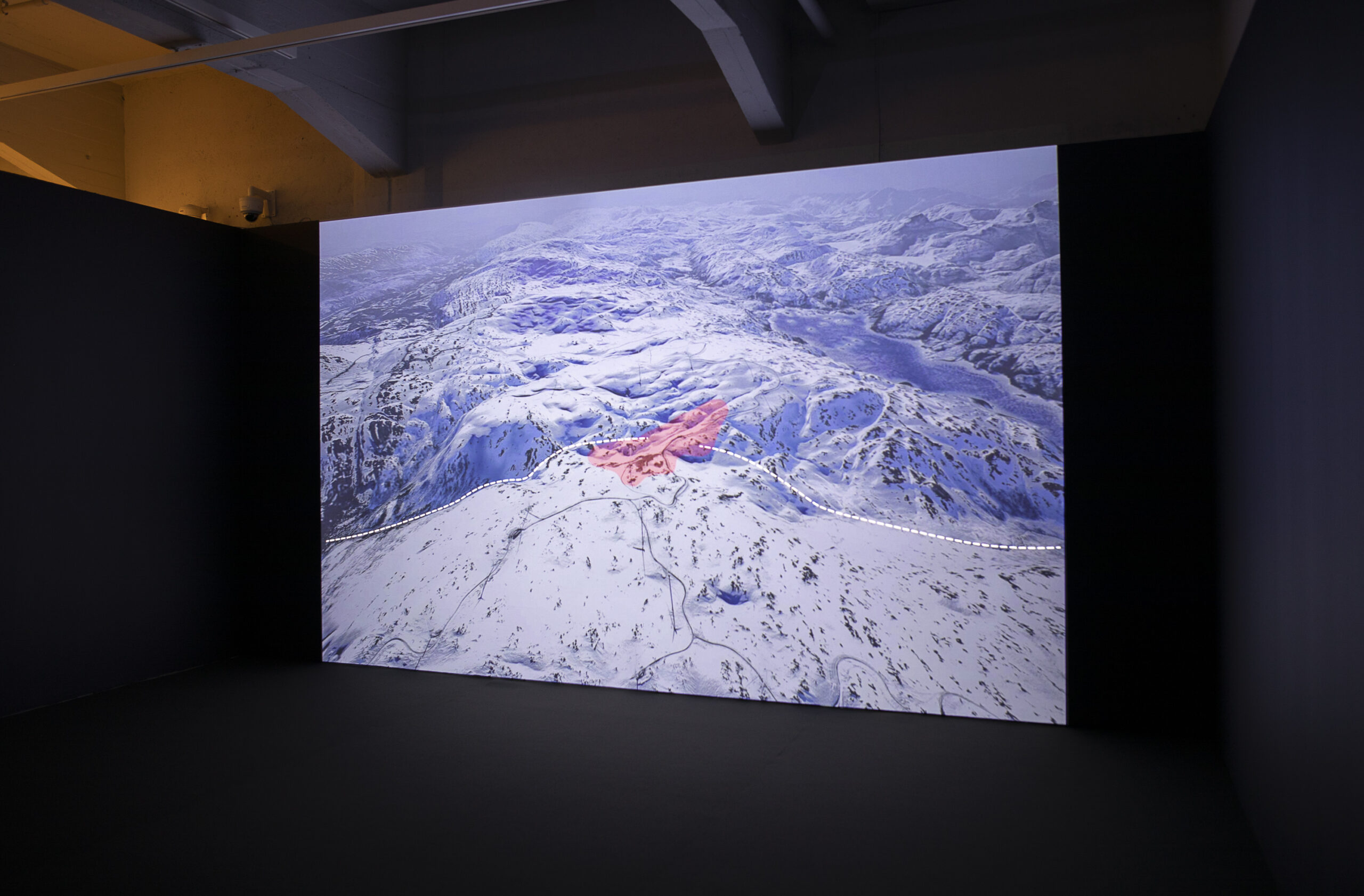

The question of who gets to decide what is detrimental to nature—in the context of a commonly natural instinct to survive—found its response in Colonial Present: Counter-mapping the Truth and Reconciliation Commissions of Sapmi (2023). This extensive installation of photographic, video, and diagrammatic evidence highlights the historical struggles of the indigenous Sami over their rights to ancestral lands across Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Russia. One video report, Treacherous Journey (2023), models the impact that one of Norway’s largest onshore wind energy projects, covering more than 40 square kilometers, has had on the Sami of the Jillen Njaarke district. Using Sami testimonies combined with publicly available spatial and environmental data, INTERPRT created a 3–D model of the wind park to demonstrate how its construction disrupted the seasonal cycles and migration patterns of Sami reindeer herding.

INTERPRT, Colonial Present: Counter-mapping the Truth and Reconciliation Commissions in Sápmi, installation view, 2023 [photo: Sonja Hyytiäinen; courtesy of the artist and HAM/Helsinki Biennial]

INTERPRT, Colonial Present: Counter-mapping the Truth and Reconciliation Commissions in Sápmi, installation view, 2023 [photo: Sonja Hyytiäinen; courtesy of the artist and HAM/Helsinki Biennial]

In Treacherous Journey, herder Ole Henrik Kappfjell describes Norway’s Oil and Energy Department giving the Sami just 55 hours to guide reindeer herds through the wind park in spring 2020, despite herders requesting one and a half months due to the distance required and treacherous conditions exacerbated by the wind park’s destruction of the natural landscape. The short timeframe, Kappfjell notes, defies the tenets of Sami animal welfare—a concept related to Sami ancestral knowledge in which migration is never just a line on a map but a holistic relationship with a living environment. Of course, the Norwegian state and ØyfjelletWind have shown scant regard for such ideas, despite assertions that the wind park is a local initiative, “with broad support from the local population and among local decision-makers.” In fact, the Sami were given little say in the wind park’s construction, which contravenes the Norwegian reindeer herding act that protects against the blocking of reindeer migration routes.

All of which highlights an ongoing process of erasure by exclusion enacted under the greenwashing guise of environmental care, which Sami artist Matti Aikio’s moving–image and sound installation Oikos (2023), confronted on Vallisaari. Installed in an old casemate, a square screen superimposes footage of reindeer wandering the snowscape over shots of wind turbines, before drifting to imagery of a sunlit lake. Grainy images, coupled with rich soundscapes, invoke a sense of time passing. These images call back to generations of Sami who fought to maintain their way of life on Indigenous lands; those who witnessed the 1852 Kautokeino Rebellion, which erupted after the Norway-Finland border’s closure cut off the seasonal migration path of Sami herders—partly prompted by complaints from Finnish settlers—and those who fought to protect Sami lands from industrial foresting and hydropower in the 20th century.

Diana Policarpo, Ciguatera, installation detail, mixed media installation, 2022 [photo: Sonja Hyytiäinen; courtesy of the artist and HAM/Helsinki Biennial]

The wind turbine, in this context, is yet another instrument of industrial exploitation to which the earth and its peoples have long been subjected. It is one manifestation of a green colonialism that extends the link between the Nordic-Baltic region to the western Sahara that PHOSfate etches. In 2021, for example, a representative of the Sahrawi liberation movement, Polisario Front, presented an unofficial climate plan at COP26. It outlined how the Moroccan state greenwashed its occupation of Sahrawi land by developing renewable energy there—without Sahrawi consultation—thus threatening such Sahrawi traditions as nomadic herding. From the Sami to the Sahrawi, at the heart of such struggles are ways of living that consider nature an active collaborator in the common survival of life on Earth. Given the pile-on of extreme weather events that occurred around the world in 2023 alone, that perspective has never felt more vital.

The 2nd Helsinki Biennial, New Directions May Emerge, took place from June 11–September 17, 2023.