2021 Atlanta Biennial: Of Care and Destruction

Of Care and Destruction, installation view, 2021 [courtesy of Atlanta Contemporary]

Share:

Following a nine-year hiatus since its previous edition, the Atlanta Biennial was resurrected by Atlanta Contemporary in 2016 to present works by more than thirty artists from ten Southern states. The subsequent edition—A thousand tomorrows, which opened in January 2019, just more than two years later—followed a similarly regional approach, including artists who hailed from Miami, Lexington, and rural South Carolina. For some viewers, each of these efforts became a test case for what an ambitious, inclusive exhibition of contemporary art from the American South could achieve. For others, however, the broad curatorial perspectives afforded insufficient space and attention for Atlanta-based artists in particular. For almost everyone involved, the emotional stakes were high, and the questions were urgent: Where does Atlanta belong in relation to the American South, or to the nation as a whole? What are the curatorial prerogatives of a contemporary art center and a biennial that bear a particular city’s name? Ultimately, how important is the Atlanta Biennial?

One large aspect that distinguishes the 2021 Atlanta Biennial from its immediate predecessors is the relative absence of such anxieties. Over the period during which the current edition was organized, the larger terrors of a global pandemic, an uprising against the national crisis of police violence against Black people, and an attempted coup by white nationalists overshadowed such considerations. In light of those conditions, it feels like a small miracle to attend an exhibition at all. Partly as a result, a sense of softness and tenderness pervades Of Care and Destruction, the main portion of this year’s biennial curated by Jordan Amirkhani, which occupies the central galleries. In no way does this tenderness diminish the ambition or skill of participating artists, or render the questions raised by the biennial’s previous editions irrelevant. Rather, it is a relief to simply witness what artists have been working on for the past year, isolated like the rest of us, without feeling hampered by cultural self-consciousness.

Hasani Sahlehe, Won’t Have to Cry No More, 2020, acrylic on canvas, 58 x 48 inches [courtesy of the artist and Atlanta Contemporary]

Marianne Desmarais, installation view of anti-forms, 2.2h, anti-form 8, and anti-form 9, synthetic rubber and found objects [courtesy of Atlanta Contemporary]

At the exhibition’s outset, and just within the front entrance, Amirkhani confidently foregrounds the work of two Black women artists from Atlanta, Lillian Blades and Shanequa Gay. What is your reflection?—Blades’ shimmering mixed-media installation composed of colorful reflective tiles, shards of mirror, and swatches of fabric—is among the most intricate and impressive works in the show, as visually rewarding at a distance as upon closer inspection. Some tiles show photographic images of smiling Black figures, a cluster of bicyclists, or a stretch of road at sunset, whereas others convey a wondrous marbled surface. This work hangs like a semi-transparent curtain in front of Gay’s mural on the gallery wall, the true manifestation of the garden of bonnevilles, sacrifice, and black abundance. This work draws upon the signature style Gay has developed in recent years, in which she creates elaborately designed motifs that reflect African American folklore, Southern Black traditions, and her own personal connections to Atlanta’s West End. True to this setting, the imagery of roosters, watermelons, and a Pontiac Bonneville imparts the sort of vivacity and humor in Outkast lyrics.

Lillian Blades, What is your reflection?, 2021, mixed-media assemblage installation, dimensions variable [courtesy of Atlanta Contemporary]

On a larger scale, installation-based works by Black artists from Atlanta form the cornerstones of the entire exhibition. Zipporah Camille Thompson’s boo hag blue, casting stars into swaddle cloth uses cinder blocks, ceramic vessels, and suspended netting to construct a memorial or altarlike space honoring the lives of Black women killed by police—women and girls such as Breonna Taylor and Aiyana Jones—as well as Riah Milton, a Black trans woman slain in Ohio last year. In another standout installation, Yanique Norman presents the sharpest-yet iteration of her ongoing Last Ladies series, which combines official portraits of American First Ladies with mugshots of incarcerated Black women. As in previous works, Norman layers countless copies of these mugshots on xerox paper to create bulging, fantastical forms rising up from the First Ladies’ stately gowns, fusing together historical critique and science fiction–tinged speculation. After Norman spent years developing this distinctive visual vocabulary, her diptych, Chytrids: Last Lady of the United States Corregidora-Lincoln, LLOTUS reveals a new level of precision and audacity in its execution. Nearby installations by Davion Alston and William Downs similarly demonstrate that each artist is refining his techniques. For Alston, this refinement takes shape through the deft integration of photography, collage, and installation into a single work. Downs, in similar fashion, incorporates animation into one of his recognizable large-scale ink-wash drawings.

Zipporah Camille Thompson, boo hag blue, casting stars into swaddle cloth, 202, mixed media, dimensions variable [courtesy of the artist and Whitespace Gallery, Atlanta, and Atlanta Contemporary]

All installed in the largest gallery, these four exceptional works feel distinctly in conversation with one another, offering the sort of loose cohesion one hopes to find in a compelling group exhibition. Similar connections animate relationships between such works as Myra Greene’s textile-based Piecework #49 and Cumberland Island (Sea Camp), a tentlike structure created by Katie Hargrave and Meredith Lyn. The work’s vinyl exterior visually mirrors the sectioned panels of Greene’s installation. But throughout Of Care and Destruction, other artworks don’t receive equal contextualization or textual emphasis, or else it pales in contrast with that of their neighbors.

Yanique Norman, Chytrids: Last Lady of the United States Corregidora-Lincoln, LLOTUS (So they lie), 2021, digitally-manipulated found image, tinted and transferred onto archival mural, silver and watercolor papers with hand-cut and sculptural elements, colored xerox, collage, graphite, and iridescent medium, dimensions variable [courtesy of the artist and Atlanta Contemporary]

For example, in addition to its large scale and prominent placement, Norman’s installation also includes a QR code that leads to a 45-minute audio collage that the artist created in collaboration with Natavia “Taves” Baillow. As rich as this offering is, the treatment it receives feels uneven compared to, for example, a close up of a black surface, one of three abstract inkjet prints by Regina Agu that are accompanied by nothing more than the sparsest material details. To a similar end, two generic floral still-life paintings by Christina Renfer Vogel and a series of fly-fishing flies made by Michi Meko feel left out alongside the more substantially contextualized artworks in the exhibition.

In all likelihood, the differing levels of detail accompanying artworks stem from a curatorial spirit that allowed each artist to be as generous or tight-lipped about their contribution to the biennial as they chose. In 2021, it’s understandable that Amirkhani might say why not? to Norman’s audio collage while also hesitating to press for more explicit information from Agu. As multiple variations on the model often do, biennials and other such large group exhibitions are capable of forming an overall, cohesive argument—but that’s not Amirkhani’s game in Of Care and Destruction. Instead of attempting to answer vexed questions of cultural authenticity or prestige, the exhibition invites viewers to closely consider each artist’s work on their own terms. Afforded this opportunity, some artists may run the risk of oversharing, while others get lost in the proverbial chorus. But, undoubtedly, some artists—in this case, particularly Blades, Gay, Norman, and Thompson—find the spotlight, hit their stride, and sing.

***

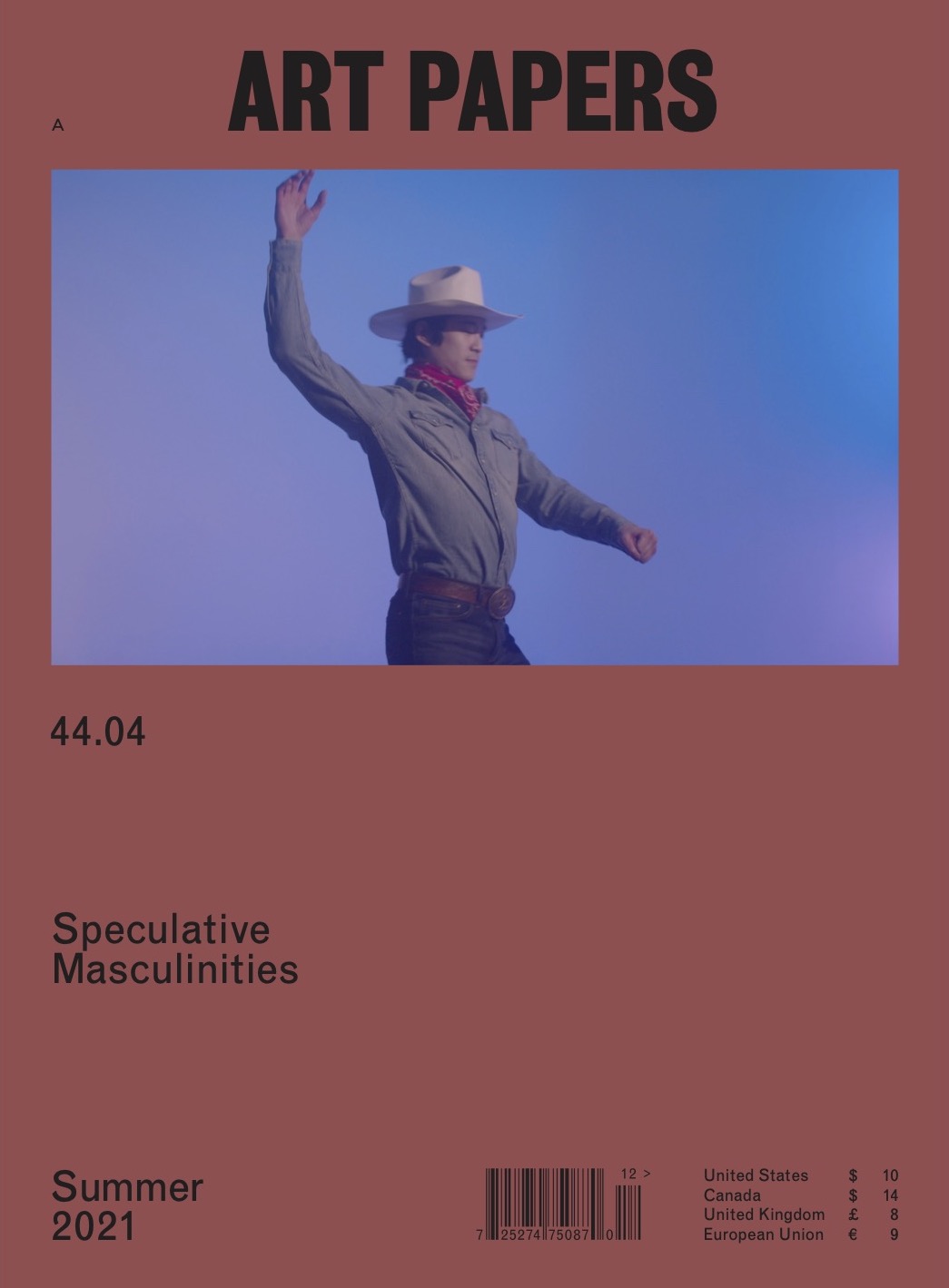

This review originally appeared in ART PAPERS Summer 2021 // Speculative Masculinities.

Logan Lockner is a writer in Atlanta. Previously, he was editor of Burnaway. His writing is included in the forthcoming monograph Toyin Ojih Odutola: The UmuEze Amara Clan and the House of Obafemi (Rizzoli Electa, September 2021).