12th Berlin Biennale: Still Present!

Tammy Nguyen, Jesus meets his Mother (detail), 2022, Watercolor, vinyl paint, pastel, metal leaf on paper stretched on foam board mounted on wooden frame 66 x 55 inches [photo: Chris Gardner; courtesy of Lehman Maupin, New York, Hong Kong, Seoul, London]

Share:

It took time for my thoughts on Still Present!, the 12th Berlin Biennale, to settle. At first, my impressions veered from one extreme to another, much like the spectrum between which the artworks composing Kader Attia’s curatorial effort oscillate without reprieve. This affect is par for the course in Attia’s artistic practice, which explores questions of repair by exposing an infliction and insisting that people look, here, at “all of the wounds accumulated throughout the history of Western modernity.”

Antonio Recalcati, Enrico Baj, Erró, Gianni Giancarlo Dova, Jean-Jacques Lebel, Roberto Crippa, Grand tableau antifasciste collectif [Large collective antifascist painting], 1960, painting and collage on canvas, 157 x 196 inches [courtesy of the artists and the 12th Berlin Biennale]

Two works encapsulate the show’s incessant movement between revelation and rage. The first is Grand Tableau Antifasciste Collectif, a massive painting at the KW Institute for Contemporary Art. Created in 1960 by Enrico Baj, Roberto Crippa, Gianni Dova, Erró, Jean-Jacques Lebel, and Antonio Recalcati, this entanglement of figures is a furious protest against the French army’s use of torture and rape to extract a confession from Djamila Boupacha—a member of the National Liberation Front, which was fighting for Algerian independence—after an attempted bombing in Algiers. In the biennale catalogue, Blandine Chavanne describes an ashen figure with open legs that Lebel painted as Boupacha’s “scarcely legible effigy and silhouette.” And it’s true; it appears like a negative space in the pictorial density. Clearer images show up elsewhere. A bold Nazi swastika references the “Gestapo-like torture methods [used] by French authorities” in Algeria; the word Setif points to the site where the French army, after participating in the liberation of Europe in 1945, massacred Algerians who were protesting for their freedom.

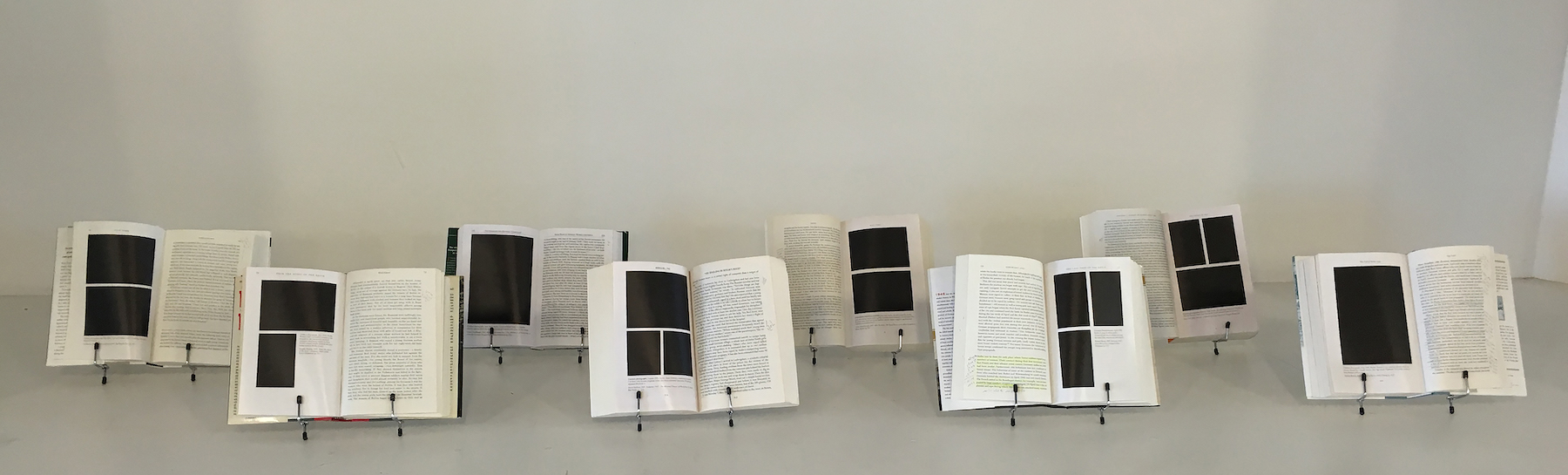

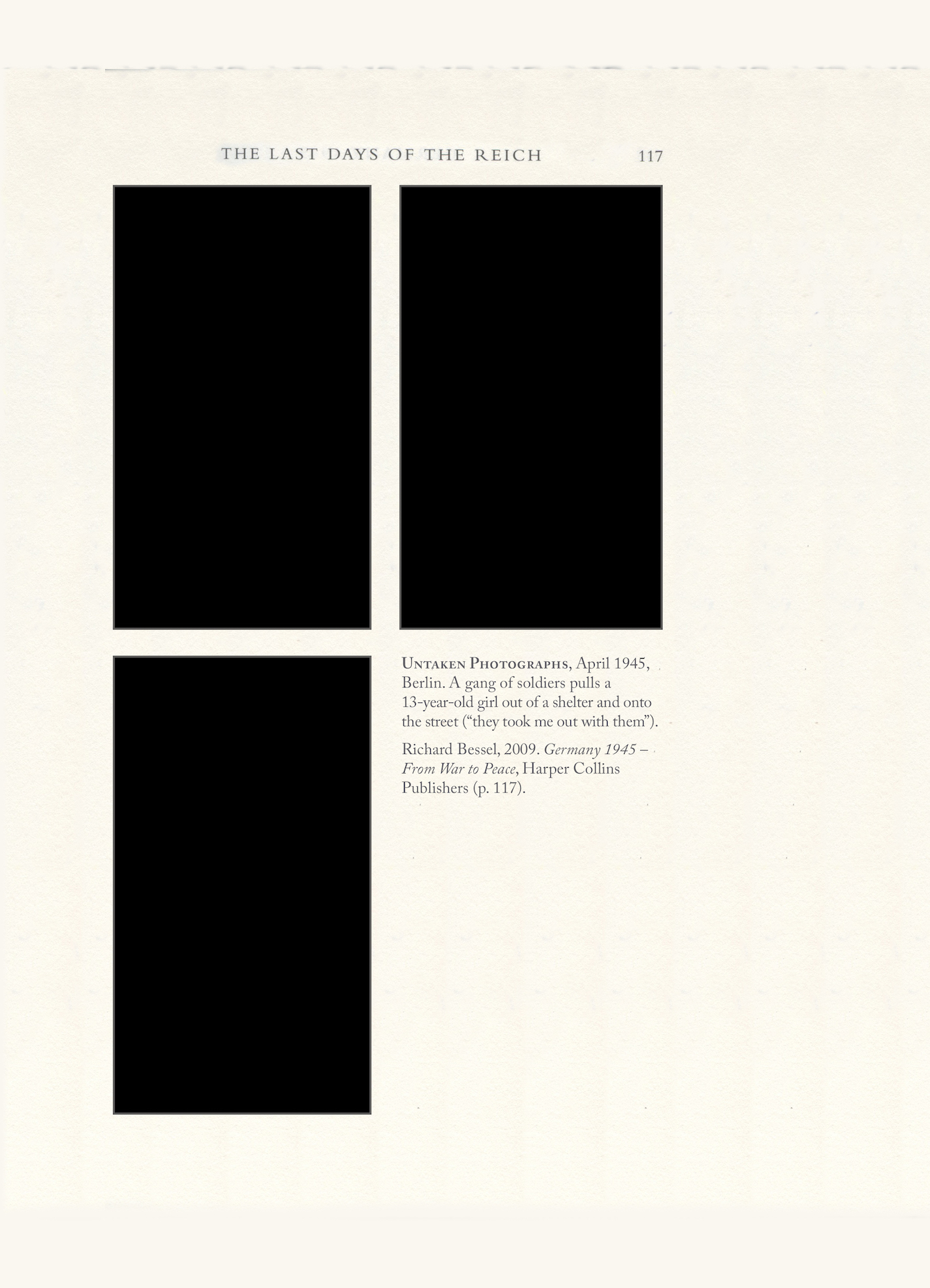

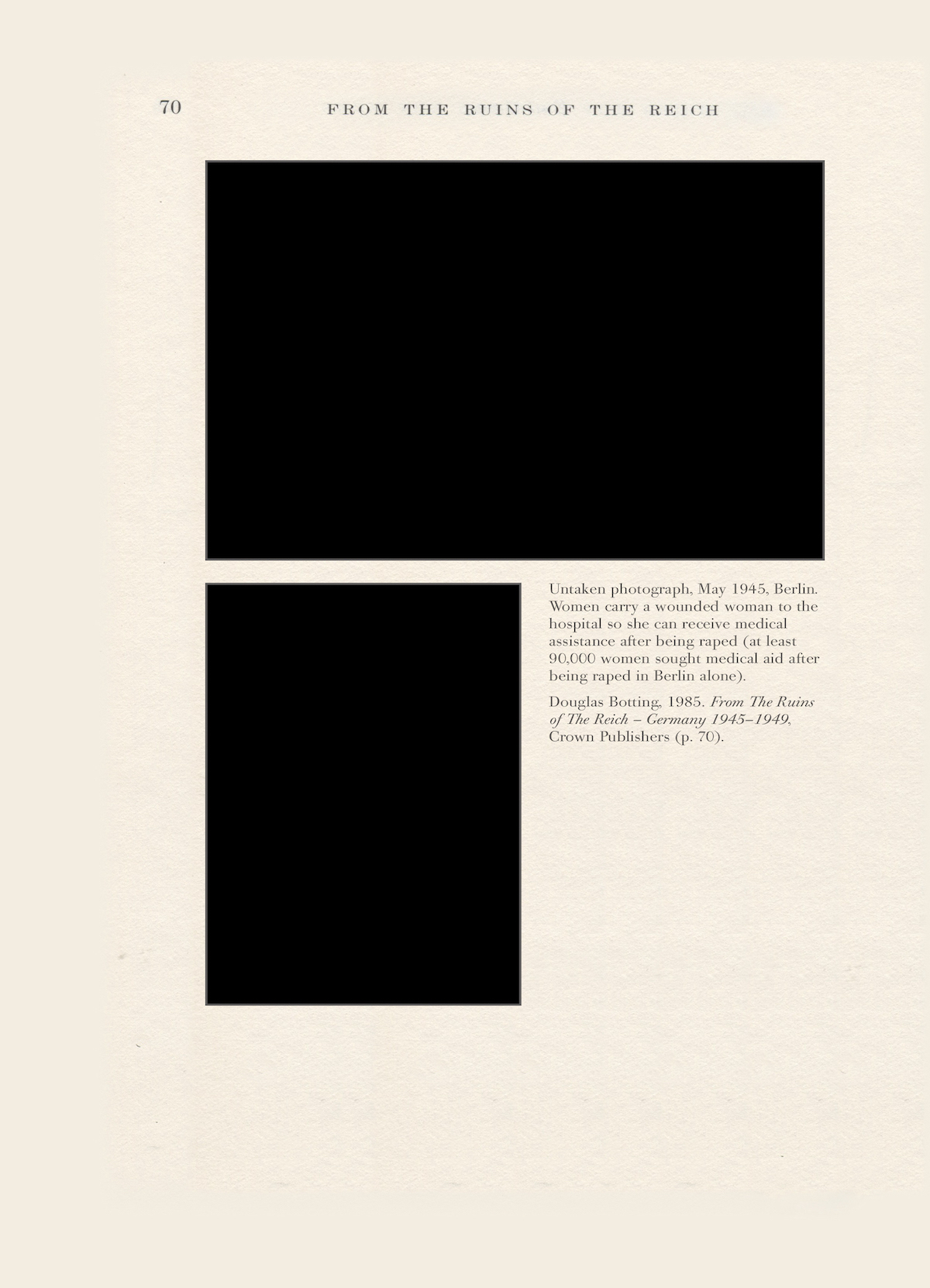

Ariella Aïsha Azoulay, The Natural History of Rape, 2017/22, Vintage photographs, prints, untaken b/w photographs, books, essays, magazines, drawings [courtesy of the artist and the 12th Berlin Biennale]

The painting is a monumental work of anti-colonial protest art. It is installed next to Ariella Aïsha Azoulay’s The Natural History of Rape (2017/2022), an arresting archival installation that documents the mass rape which occurred in post–WWII Berlin. A timeline organized by quotes drawn from one woman’s contemporaneous diary runs horizontally along the wall, above a printed essay written by Azoulay, with endnotes connecting to photographs and documents around it. The essay opens by recounting the experience of writer Marguerite Duras in Paris, as she listened to Charles De Gaulle declaring the war’s end. “‘We shall never forgive,’ [Duras] stated, using a non-patriotic ‘we’ to refer to those co-citizens who resisted both the national identities assigned to them on the map of war and the precept to celebrate disasters inflicted upon some and to mourn for others,” writes Azoulay.

Ariella Aïsha Azoulay, The Natural History of Rape (detail), 2017/2022, Vintage photographs, prints, untaken b/w photographs, books, essay, magazines, drawings, Dimensions variable [courtesy of the artist and the 12th Berlin Biennale]

Ariella Aïsha Azoulay, The Natural History of Rape (detail), 2017/2022, Vintage photographs, prints, untaken b/w photographs, books, essay, magazines, drawings, Dimensions variable [courtesy of the artist and the 12th Berlin Biennale]

Azoulay’s thoughtful display confronts the binary oppositions that war so often imposes by highlighting the victims caught between the lines, and it does so with care. Images in open books are covered, including one whose caption describes a 13–year-old girl pulled from a shelter by a gang of soldiers. These acts of respectful obfuscation do not detract from the work’s condemnation. Compare that approach with Poison Soluble, Lebel’s second contribution to Still Present!, which the artist created solo in 2013. At the Hamburger Bahnhof, a small room has been turned into a claustrophobic maze formed by enlarged images of Iraqi prisoners being tortured by US soldiers at Abu Ghraib. This gratuitous, direct reproduction of graphic violence—these images have been hypercirculated in the public domain—is an infuriatingly pointless and inherently violent provocation. It shows no regard for the people effectively being dehumanized again, just so a European artist—and, indeed, the Berlin Biennale’s artistic director—can make a point, causing real harm in the process.

The work’s weak reliance upon a quote by Frantz Fanon—printed at the exit to Lebel’s fucked–up spectacle, as if to validate the endeavour—doesn’t help. A Black revolutionary’s words are basically co-opted to justify a moralistic display enacted at the expense of Arab bodies. Part of the quote reads: “The only possibility of regaining one’s balance is to face the whole problem.” Yet that “whole problem,” as demonstrated in this work and its placement in this show, includes the Eurocentrism embedded not only into the rhetoric of exhibitions staged by Western institutions intent on performing decoloniality rather than enacting it, but also in the actions of those agents whom institutions appoint to perform that “decolonial” service on their behalf. Erasures and otherings happen in gestures like these—even when there are good intentions. Take Grand Tableau Antifasciste Collectif, where the contributions of Afro-Cuban Chinese artist Wifredo Lam were reportedly painted out by his European “comrades,” a point not mentioned in the wall text.

Lebel’s two works occupy an unforgiving space that Attia’s curatorial direction opens up, at once on purpose and by dint of its audacious disregard for the traumas of others, amid veering from a kind of archive-centered testimonial porn with no aesthetic or ethical merit on one end to artworks that demonstrate exemplary aesthetic care on the other.

Tammy Nguyen, Jesus meets his Mother, 2022, Watercolor, vinyl paint, pastel, metal leaf on paper stretched on foam board mounted on wooden frame, 66 x 55 inches [photo: Chris Gardner; courtesy of Lehman Maupin, New York, Hong Kong, Seoul, London]

That destabilizing, uneven enmeshment, however, seems to be the dark heart of Attia’s thesis, which frames imperialism as a clusterfuck that entangles everyone in its unbearable contradictions, whether we like it or not. Take Tammy Nguyen’s 14 blue-scale paintings that stage the stations of the cross in a Catholic park located inside a Vietnamese refugee camp on the southeast Asian island of Pulau Galang. “Catholicism is a colonial legacy, yet it offers many Vietnamese people salvation and prayer that is true and vivid,” writes Nguyen. That contradictory tension is likewise expressed in a historical presentation at the Kunstakademie der Künste, Pariser Platz. There, paintings by German expressionists Emil Nolde and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, which depict African artifacts, surround a platform of wooden crucifixes—drawn from European collections—that were crafted by indigenous peoples of Africa and Papua New Guinea. The catalogue posits Nolde’s paintings, in particular, as expressions of an opposition to colonialism that still exoticized their subjects, whereas the wooden sculptures are framed as “hybrid objects … shown as an early reaction of colonised subjects against the occupant, the earliest form of reappropriation and resistance.” Look closely and what emerges are expressions of Black Jesus.

Tammy Nguyen, Jesus meets his Mother (detail), 2022, Watercolor, vinyl paint, pastel, metal leaf on paper stretched on foam board mounted on wooden frame 66 x 55 inches [photo: Chris Gardner; courtesy of Lehman Maupin, New York, Hong Kong, Seoul, London]

Noel W Anderson, installation view, 12th Berlin Biennale [photo: Laura Fiorio; courtesy of the artists and the 12th Berlin Biennale]

Birender Yadav, installation view, 12th Berlin Biennale, Hamburger Bahnhof, Berlin [photo: Laura Fiorio, courtesy of the artist and the 12th Berlin Biennale]

The evolution of racial capitalism’s imperialist and settler–colonialist violence is mapped throughout Still Present! Noel W Anderson’s cotton tapestries, made from photographs that document the policing of Black bodies, speak to an oppressive endurance of systemic harm. Fabrics are stretched, distorted, distressed, picked, and, in some cases, hung like suspended sculptures, as with Hood Dreams I (2019–2021), in which a color image of a police search is barely discernible through its folds. Anderson creates these works with Jacquard technology, whose invention at the turn of the 19th century coincided with Britain’s abolishment of slavery, and later informed the binary coding of computational systems. The British Empire’s subsequent reliance upon Asian indentured labor across its colonies continued the extractive ideology of progress, whose human effects are brought into the 21st century in Birender Yadav’s intimate homage to workers exploited for India’s development. The work on paper Donkey Worker (2015) depicts a donkey created with thumbprints of migrant laborers from Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, working in Delhi. It is installed alongside the series Erased Faces (2015), photographic portraits of brick–kiln workers in Uttar Pradesh that have been marked by their thumbprints, and Walking on the Roof of Hell (2016), a pile of 30 wooden sandals used by workers to withstand the heat of the kilns.

Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme, Oh Shining Star Testify, installation view, 2019/223-chanel video installation, 2-channel sound, subwoofer, 10 minutes, 5 seconds, wooden boards [courtesy of the artist and the 12th Berlin Biennale]

The fact that imperialism’s crimes are not solely perpetrated by European and American powers is something Attia’s exhibition seems to highlight, all while the artistic director himself infuriatingly extends that violence through the inclusion of a work as indefensible as Poison Soluble. Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme’s Oh Shining Star Testify (2019–2022) is a powerful multiscreen installation centering on Israeli military surveillance footage that captures the killing of 14-year-old Yusef Al-Shawamreh, who crossed the Israeli separation wall to pick akkoub—an edible plant, important in Palestinian cuisine, whose foraging the Israeli state made illegal. Asim Abdulaziz’s short film 1941 (2021) draws a red thread from the current Saudi-led war in Yemen, which is backed by the UK and the US, to WWII. Ten shirtless men of different ages are seen knitting red wool inside an abandoned Hindu temple in Aden—the artist’s response to learning how American women contributed to the WWII effort by knitting.

Hasan Özgür Top, The Fall of a Hero, 2020, Full HD video, color, sound, 14 minutes, 48 seconds, Video still [courtesy of the artist and the 12th Berlin Biennale]

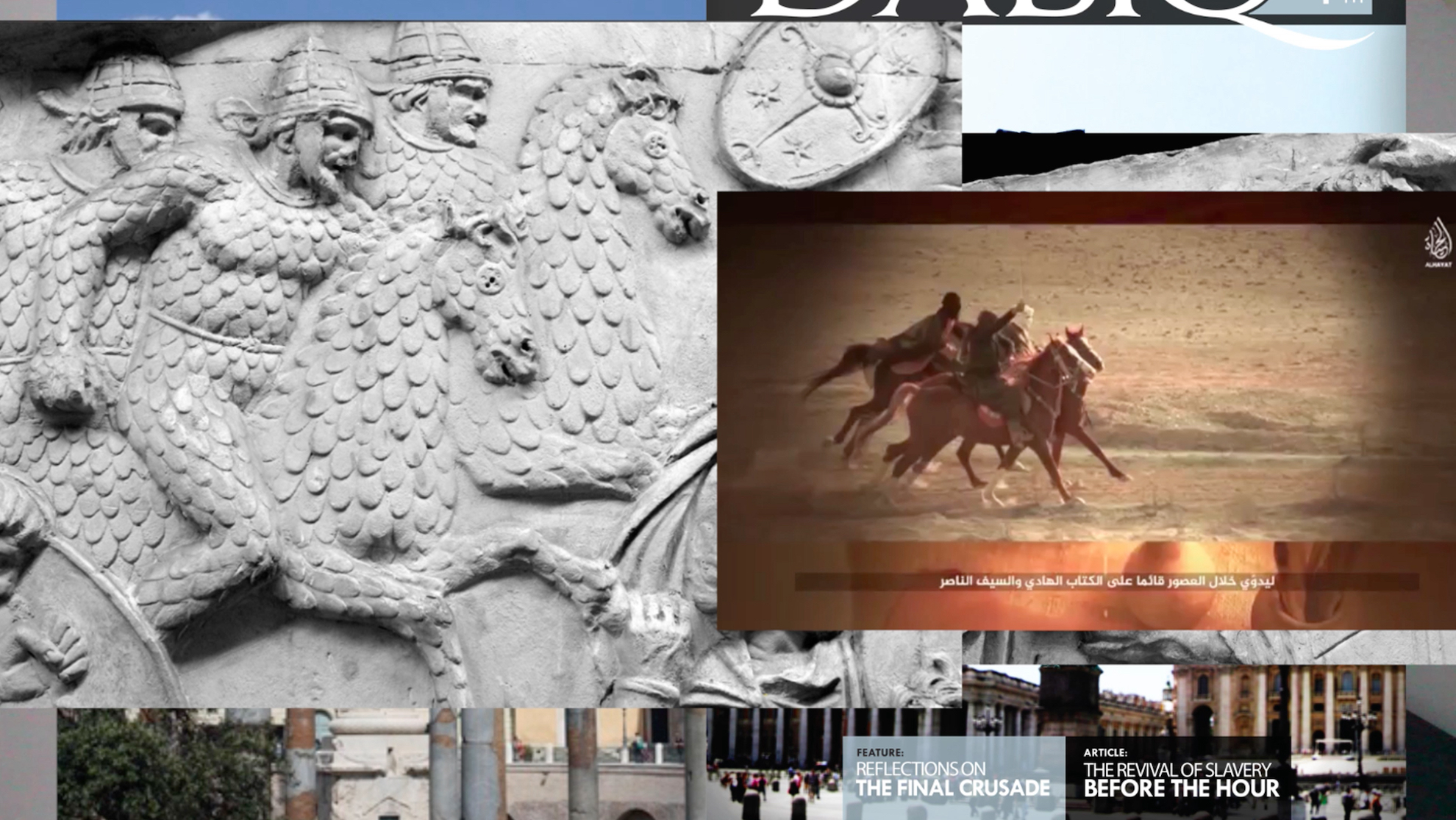

That sense of historical circularity, which pervades Still Present!, is amplified in Hasan Özgür Top’s The Fall of a Hero (2020), installed at the former Stasi Headquarters, now a museum. This incisive video features the artist performing the role of suspect in an interrogation room. He uses the Trajan typeface—inspired by the text inscribed onto the base of a column in Rome that was once topped with a statue of Emperor Trajan—to draw connections between the imperialist desires and actions of ISIS and the United States. As Top speaks, examples of Daesh propaganda using the Trajan font appear on screen, as well as instances in which that font is seen in American visual culture, from its political theater to Hollywood films and video games glorifying military combat. What emerges is a global competition—not so much a clash as an exhausting, ouroboric race—where patriarchies vie to crown a phallic symbol of global power with their own patriarchal effigy.

That dynamic—a seemingly endless Manichean clatter of forces in which everyone suffers—is what this exhibition unfolds, as it wrestles with everything all at once and asks its audience to do the same. The only issue is that, with its relentless shifts, insistent densities, and glaring missteps, which sometimes enact the violence this show supposedly stands against, it takes time and patience to meaningfully engage. Otherwise, you end up taking sides, and stories worth hearing get lost in the fray.

Stephanie Bailey is editor in chief of Ocula magazine, a contributing editor at LEAP, and a regular contributor to Artforum International, Yishu: Journal of Contemporary Chinese Art, and dɪ’van: A Journal of Accounts. Formerly the senior editor of Ibraaz, where she worked 2012–2017, Bailey is also a member of the Naked Punch editorial committee; a managing editor of Podium, the online journal for M+ in Hong Kong; and the current curator of Art Basel Conversations in Hong Kong.