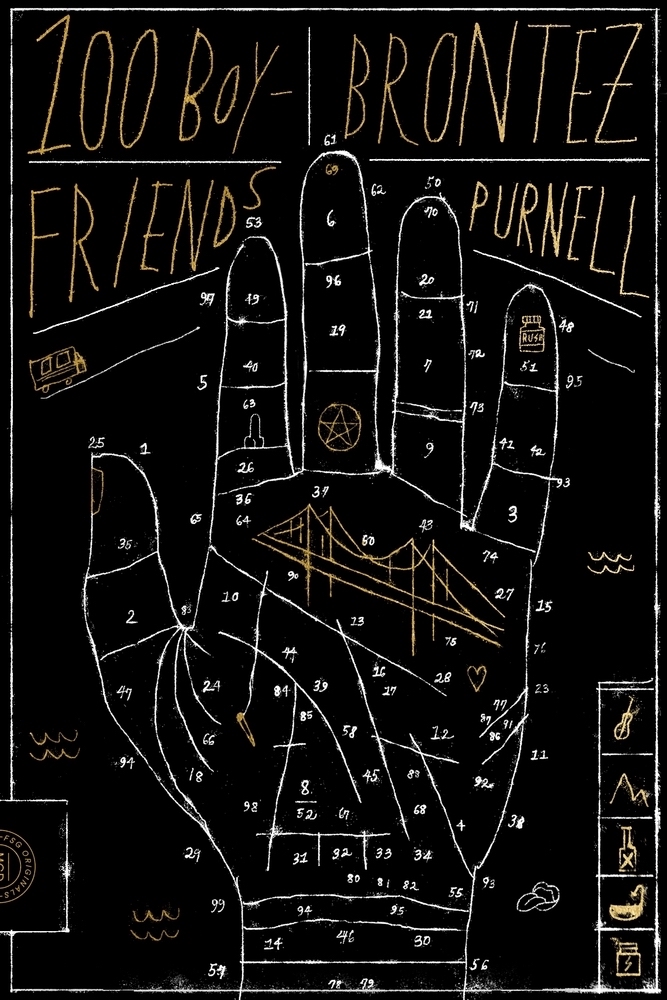

100 Boyfriends by Brontez Purnell

Share:

100 Boyfriends, Brontez Purnell’s latest book, is a beautifully acerbic and transgressively messy portrait of queer existence—and persistence—that celebrates implosion and transcendence while questioning the desire to delineate the two. In the lineage of new narrative writers such as Kevin Killian, Kathy Acker, and Cookie Mueller, Purnell has assembled a collection of stories wherein boyfriends are both the subject and the device through which to explore what it means to be situated at the margins of intersecting identities.

Brontez Purnell is an interdisciplinary writer, dancer, musician, and filmmaker whose work has employed a DIY/punk ethos to explore overlapping conceptions of queerness, Blackness, and masculinity. Purnell’s writing, most notably in his previous books Johnny Would You Love Me If My Dick Were Bigger and Since I Laid My Burden Down, is painfully personal and deeply funny. Both preceding books use diaristic and faux-memoir formats to address ways in which gay dysfunction, self-sabotage, and lived realities of HIV/AIDS intersect with and are complicated by race, class, and sexual identity. The themes, styles, and strategies that make Purnell’s writing so compelling are present throughout his practice; whether as the front man for his band The Younger Lovers or as the cofounder of his experimental dance group, the Brontez Purnell Dance Company, Purnell situates his work between lived and theorized experience to offer us a vernacular for disrupting and complicating dominant, reductive narratives. 100 Boyfriends is true to form and possibly Purnell’s most sophisticated and impactful work to date.

One of the most compelling and endearing qualities of 100 Boyfriends is its portrayal of the generative, even productive, aspects of dysfunction. The characters in Purnell’s writing are often in the midst of making what one might assume to be a wrong decision, but they are doing so with self-awareness and a sense of humor that celebrate their foibles rather than implicating them in a moralistic tale of self-destruction. There is triumph in their persistence. In this way, Purnell ascribes agency to his characters, which allows them to be messy, charismatic, self-sabotaging, sexy, and brilliant all at once. Purnell’s writing shifts effortlessly between tawdry bluntness and erotic profundity, and it is often impossible to tell the difference. 100 Boyfriends is filled with these moments of complication, each of which is a testament to Purnell’s expertise as a purveyor of sloppy-sexy prose. One such moment—from the chapter “Meandering (Part Two)”—is emblematic of the way Purnell’s characters are often caught in moments of self-observation, where sexuality is both physical and existential. The narrator is having sex in the unfinished apartment complex gym of a man whom he meets on his walk home from the reading of a friend’s play:

I fucked him doggy-style because it’s the easiest way for two strangers to cum. He was facedown pretending that I was someone else. I was watching him facedown pretending that he was someone else. He was facedown pretending that he was someone else. I was watching him facedown pretending I was someone else.

It was over soon.

Purnell’s generative dysfunction is also present in the formal qualities of the book itself. Most notably, the title 100 Boyfriends establishes a premise that is then playfully disregarded, echoing the themes of transgression, fluidity, and complication that define the subject matter of Purnell’s stories. The title creates an expectation that each story might correspond to a different individual whom the author considers a boyfriend. Instead, “boyfriend” is developed as an operative term to explore how it exists in multiplicity as an aspirational, descriptive, performative, and pejorative distinction. In the chapter “Mountain Boys,” boyfriend comes to represent desire in all its complexity: desire to love and to be loved, to be wanted, to be remembered, and to persist. Purnell’s character is lying in the bed of a lover, reflecting on their shared history and his feelings of rejection. He imagines the room to be populated by 100 ghosts of boyfriends-past, his baggage:

What are the mechanics of desire? In what feels like all of three seconds my mind spins into a hard flashback on past lives—men I loved, some of who I eventually hated; they are all still there somewhere, all hovering around. I called them “boyfriends,” though this was not always the case. But they were all like pieces of bubblegum you chew hours after the flavor leaves and that you accidentally swallow, and then (supposedly) sit in your guts for seven years.

Even here, 100 functions figuratively rather than quantitatively, as a gesture to “the many.” Purnell’s writing has an elegantly circular quality, using refrain and repetition to build a charismatic and messy voice all its own.

Christopher Robert Jones is an artist and writer based in Illinois. Their research revolves around the “failure” or “malfunctioning” of the body and how those experiences are situated at points of intersection between Queer and Crip discourses. Jones received BA degrees in art studio and technocultural studies from UC Davis and an MFA from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, where they are currently a specialized faculty in new media.