Avantika Bawa: APEX and Coliseum

Avantika Bawa, APEX, installation view, 2019 [courtesy of artist and Portland Art Museum, Portland]

Share:

Avantika Bawa’s APEX and Coliseum examine a Portland, OR landmark that stirs halcyon memories among several generations of architecture and sports lovers in the Pacific Northwest. In these complementary exhibitions, which overlapped for two months last fall, Bawa united nostalgia with geometric rigor in a paean to the Veterans Memorial Coliseum, an arena that has twice narrowly escaped demolition during Portland’s recent building boom. Bawa’s exhibition at Portland Art Museum [August 18, 2018–February 10, 2019] is the latest installment of APEX, an ongoing series showcasing Northwest-based artists; the other—across the Willamette River about three miles from the coliseum itself, was part of Ampersand Gallery & Fine Books’ [September 27–November 25, 2018] engaging program of rotating shows. Although the coliseum comprised both exhibitions’ subject matter, the artist’s divergent approaches to composition, media, light, and color gave each show a unique character.

Opened to the public on November 1, 1960, the Veterans Memorial Coliseum was designed by Skidmore, Owings, & Merrill LLP, the still-prominent architecture firm behind renowned contemporary buildings such as the Burj Khalifa in Dubai and One World Trade Center in New York City. With its striking glass-curtain wall encasing a circular stadium, the coliseum is exemplary of the austerely elegant international style. In Bawa’s essay from Ampersand’s catalogue, APEX curator Grace Kook-Anderson describes the structure as “a bowl housed in a box, the box shell made light with glass and steel.” In the same publication, architecture critic Brian Libby likens it to “a skyscraper that has been laid on its side, with more than 80,000 square feet of glass” enveloping 341,300 square feet of floor space. Although many viewed the building as an incongruous addition to a city once nicknamed “Stumptown” in the heart of the woodsy Pacific Northwest, the coliseum’s design, according to Libby, did incorporate some strategic nods to the region’s timber industry, among them cozy, wood-paneled conference rooms and the broad wooden strip that crowns the façade. The arena acquired new popularity when, from 1970 to 1995, it became the official home of the Portland Trail Blazers basketball team.

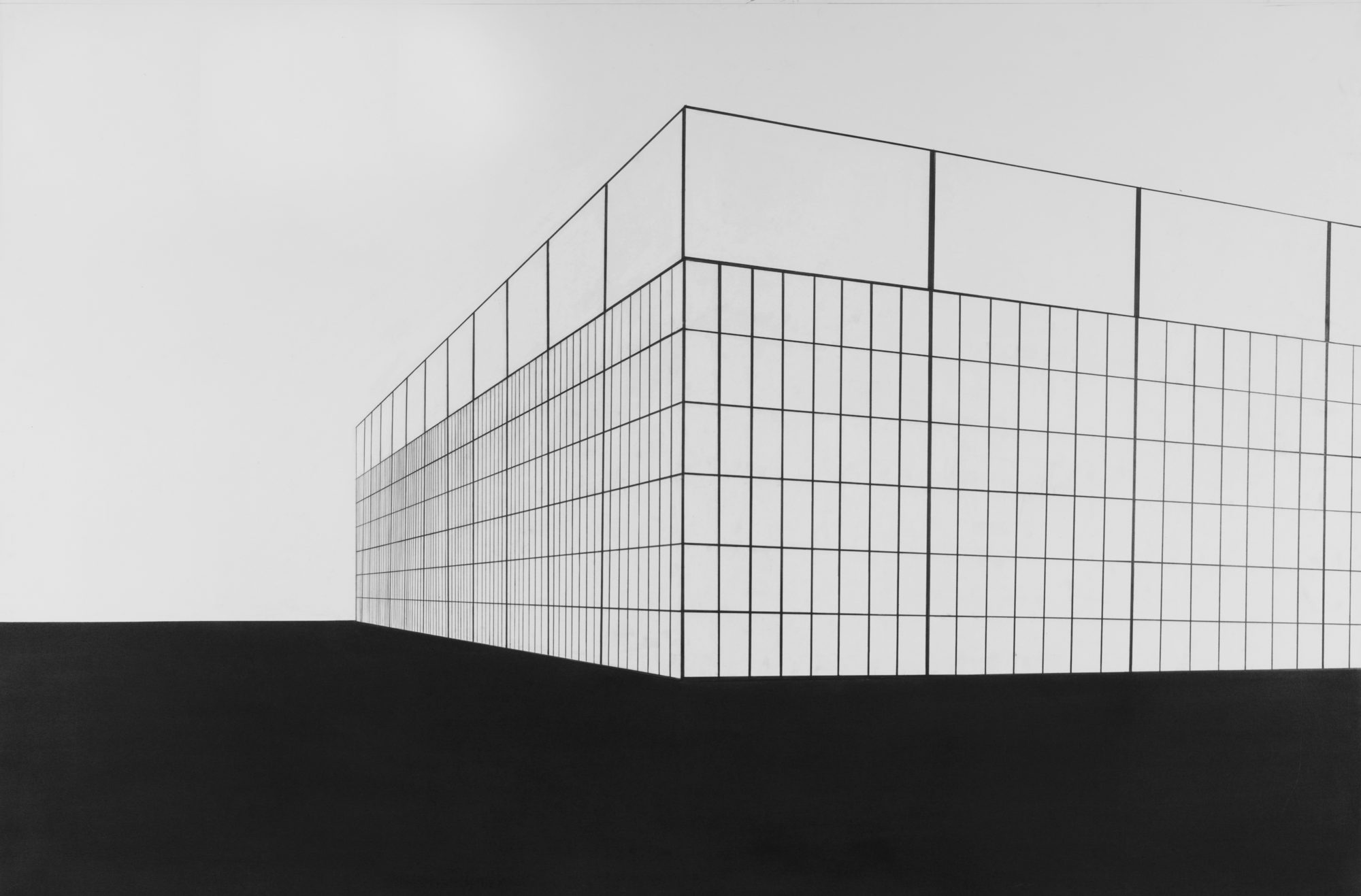

Avantika Bawa, Coliseum 17, 2017, graphite and pastel on paper, 40 x 64 inches [photo: Dale Strouse; courtesy of the artist and Ampersand Gallery, Portland]

Bawa’s inventive, confidently executed renderings—with their obsessive permutations of graphite, pastel, acrylic, charcoal, and oil pastel—are overlaid by a sense of poignancy and urgency, given that this now celebrated structure has twice narrowly escaped demolition, once in 2009 to make way for a minor-league baseball stadium, then again in 2014 for a residential project. For the time being the wrecking balls are at bay, but in the city’s metastatic development boom, one never knows when the next landmark will vanish. Into this charged context steps Bawa, an artist with a gift for activating architectural space in site-specific installations (perhaps most memorably in Mineral Spirits, her 2016 installation in the faded lobby of the John Jacob Astor Hotel in Astoria, OR). Although best known for installations, Bawa has a well-honed drawing practice, which she deploys in these two shows with keen observation and seemingly inexhaustible compositional virtuosity.

With a series of 19 works on paper at Portland Art Museum and 18 at Ampersand (all dating 2015–2018), Bawa’s overarching approach is not to portray the coliseum realistically, but to reduce its contours to their formal properties within the syntax of geometric abstraction. She has eliminated all background, landscaping, people, and almost all color, until all that remains are the façade’s implacable grids, the ground beneath them reduced to slabs of flat space. The works enfold a panoply of art-historical references, not only from the lineages of neoplasticism and hard edge painting, but also, as Kook-Anderson points out, the two-point perspective of Ed Ruscha’s Standard Station paintings, which share pictorial affinity with the diagonal side-view orientation of Bawa’s Coliseum 17. Additionally, Coliseum Red, Coliseum Cool 2b, and Coliseum Cool 2c bring to mind Peter Halley’s underground-conduit and cell imagery of the early 1980s. And though most of Bawa’s works hold forth quietly in grayscale, certain exceptions spill over with bracing color, as in Coliseum Blue, whose titular hue was inspired by 1960s-era architectural postcards from the City of Portland and University of Washington archives.

Avantika Bawa, Coliseum Blue, 2018, graphite and acrylic on panel, 80 x 120 inches [photo: Dale Strouse; courtesy of the artist and Portland Art Museum, Portland]

Avantika Bawa, Coliseum Red, 2018, photo lithograph, Printed at Crows Shadow Institute of the Arts, 29.5 x 18.5 inches [photo: Nika Blasser; courtesy of the artist and Ampersand Gallery, Portland]

Whereas most compositions at Portland Art Museum are frontal, rectilinear views, many at Ampersand incorporate curvilinear depictions of the stadium’s bowl structure visible through the exterior grid, as in Coliseum 21 and Coliseum 28. This seemingly minor difference in perspective gives the two exhibitions significantly different emotional tenors—the museum’s is exacting, imperious, Bauhaus-like, and expository; the gallery’s is softer, more user-friendly and permeable to nostalgia. Another variation between the drawings is their distinct evocations of place—not the coliseum’s literal site, but rather the places where Bawa actually made the works. The drawings completed during a Ucross residency in northeastern Wyoming, as well as lithographs created at Crow’s Shadow Institute of the Arts in northeastern Oregon, seem informed by the hard, high-desert light of the American West. By contrast, drawings completed during a residency in Skagaströnd, Iceland, are mistier, moodier in their atmospherics, exuding a sfumato that plays counterpoint to the coliseum’s obdurate Cartesian grids.

The mediums and techniques deployed across this body of work—the artist’s hand visible in exacting graphite application; the textural variations of paper pulp (three drawings at Ampersand were left unframed so surface imperfections could be more clearly seen); and the emotional associations implied by Bawa’s judicious, perhaps unexpectedly affecting use of color—come together in artworks with an emotional richness that belies the stalwart metal and glass of their subject’s materiality. The abject obsessional devotion the artist has lavished upon the coliseum via the drawings and lithographs now becomes a form of aesthetic preservation; and if the cranes and wrecking balls ever come to rip this astonishing building asunder, these exacting, yet loving, homages will stand among the objects that remind us what was lost.

This feature originally appeared in ART PAPERS “Energy Structures” Spring/Summer 2019.

Richard Speer is a West Coast-based art critic, curator, and author. His reviews and essays have appeared in ARTnews, Artpulse, Visual Art Source, The Los Angeles Times, The Chicago Tribune, The Oregonian, Salon, and Newsweek. He is the author of “Halley/Mendini” (Mary Boone Gallery, 2014), “Eric Wert: Still Life” (Pomegranate, 2018) and the forthcoming “The Space of Effusion: Sam Francis in Japan” (Scheidegger & Spiess, 2020). From 2002 to 2015 he was art critic at Willamette Week, the Pulitzer Prize-winning newsweekly in Portland, Oregon. He is curator of “Journey to the Third Dimension: Tom Cramer’s Drawings and Paintings 1974-2019,” opening August 15, 2019, at the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art, and co-curator of “Sam Francis and Japan: Emptiness Overflowing,” opening Summer 2020 at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.