The Octavia E. Butler Collection

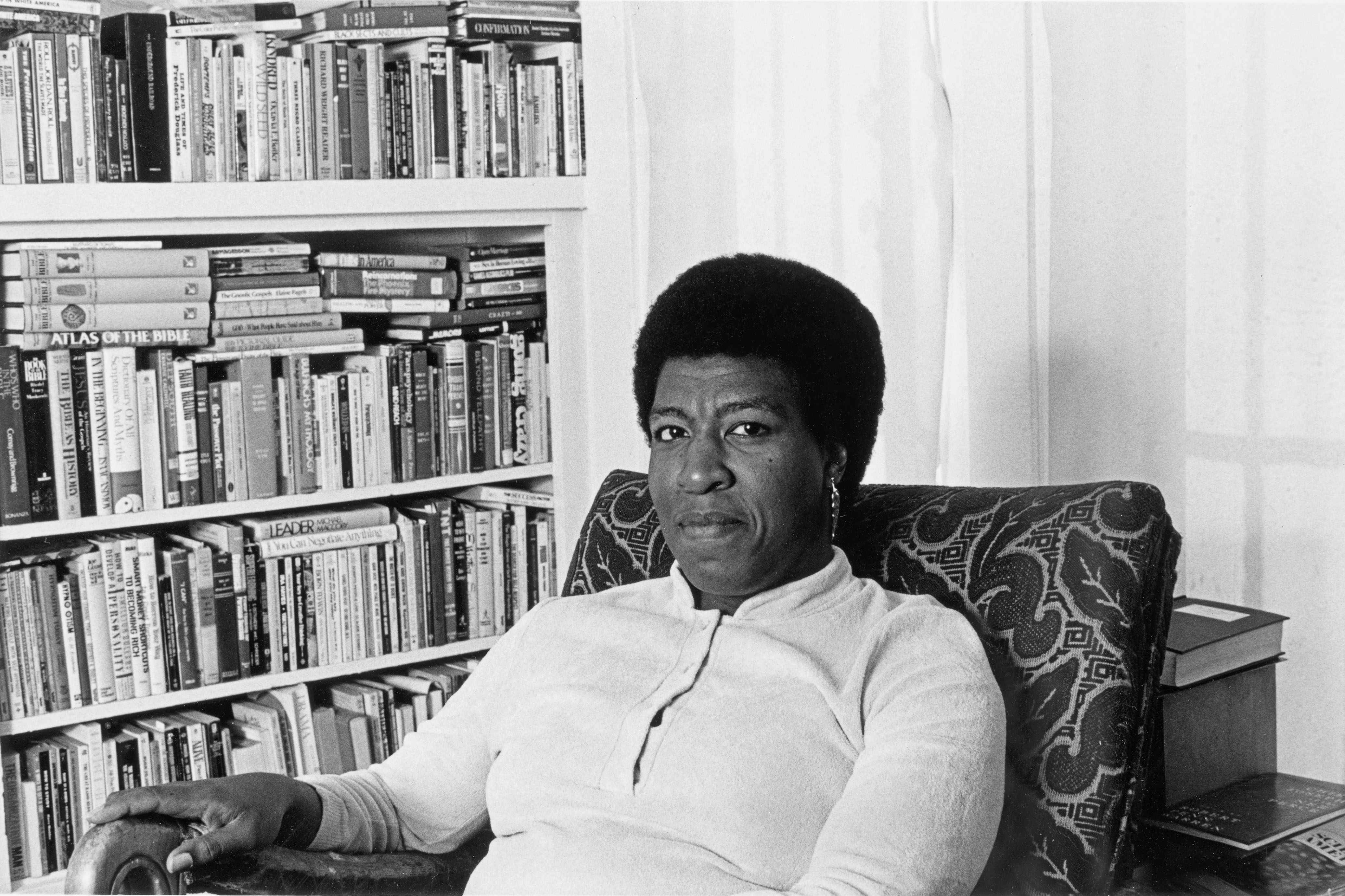

Patti Perret, photograph of Octavia E. Butler seated by her bookcase, 1986. [courtesy of The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens, © Patti Perret]

This is my life. I write bestselling novels. My novels go onto the best seller lists on or shortly after publication. My novels each travel up to the top of the bestseller lists and they reach the top and they stay on top for months (at least two). Each of my novels does this. So be it! See to it! I will find the way to do this. So be it! See to it!

Share:

So wrote Octavia E. Butler (1947-2006) inside the cover of a notebook in 1988—one of the manifestations the author jotted across her sketchpads and rough drafts, artifacts now housed in the collections of the Huntington Library in Pasadena, CA. Butler was the first science fiction writer to receive a prestigious MacArthur Fellowship. She was also the first African American woman to gain recognition in the genre, though one of her more famous statements on the topic of her contribution to that particular field, uttered during more than one interview, is “I write about people who do extraordinary things. It just turned out that it was called science fiction.” Butler herself did extraordinary things, and the story of her method of self-motivation and perseverance in the face of challenging odds, of her productivity, and of her excellence at creating worlds that reveal, and at times redress, truths about our own, is beautifully told through her archive. Here, Natalie Russell, assistant curator of literary collections at the Huntington Library in Pasadena and curator of Octavia E. Butler: Telling My Stories [April 8-August 7, 2017], a new exhibition of the pioneering author’s papers, reflects upon the meaning and urgency of these materials today.

Butler’s works, though they may have been written 20 or 30 years ago, are incredibly contemporary and relevant. She tackles issues like climate change and drought, the prevalence and testing of pharmaceuticals, the increasing gap between the rich and the poor, and sexual identity—all issues humanity still faces today—in thought-provoking ways. She is a storyteller, but she also recognized the power of science fiction to help us dream for the real world. Hers is a voice that sought a path toward a better, more peaceful, more cooperative world. She offers warnings of the malignant possibles and contemplates solutions to these dire visions.

Butler had no role model for what she was doing—a black, female, science fiction author—but was driven by her own ‘positive obsession.’ … This self-motivation can be understood from a number of angles. She believed that persistence and effort, rather than pure imagination or waiting for ‘the muse,’ were the key elements to success as a writer. She considered herself of average intelligence and not particularly talented. While I would disagree, her self-motivation may be understood as a response to her own self-doubt, [to which she applied] her interest in the mind, utilizing concepts of self-hypnosis to make things true or mantras to improve self-esteem. Her self-motivation may also be a response to the lack of widespread support. While her mother did support her writing to some extent, a career as a science fiction author was largely unfathomable to anyone in Butler’s immediate community. Butler reflects heavily in her personal writings on the challenges of writing and the lack of support systems. She wrote: ‘Should a woman who is black have to spend her writing life wondering whether the praise or criticism she is receiving comes because of her sex, or her color, or because her work is deserving of it?’ and ‘Why aren’t there more SF Black writers? There aren’t because there aren’t. What we don’t see, we assume can’t be. What a destructive assumption.’ Luckily these barriers didn’t keep Butler from pursing her passion. Her self-motivational notes can also be seen as the logical expressions of a writer with compelling personal drive. It is telling, perhaps, that it took such a woman to break into a traditionally white male genre and to become the role model for others to follow. What magnificent voices are today suppressed by the status quo?

An author’s archive provides a window into the creator behind the works—her inner struggles and processes. It can help us better understand the work, or the author’s perspective of the work, or give voice to the many things they have to say about the world that didn’t necessarily make it onto the page. Butler always wanted to tell good stories, and her archive does that. These are important stories, because they help us reflect on the past and dream of, and hopefully create, a better future.

It is often said that those who do not study history are doomed to repeat it. Butler put it this way: ‘To study history is to study humanity. And to try to foretell the future without studying history is like trying to learn to read without bothering to learn the alphabet.’ Preserving archives, and providing access to them, is a way to access history. They help us ask important questions, not just about how to be a successful writer, but about what defines success—not just, ‘How were racism or sexism experienced in the 1970s?’ but ‘What can we learn from those who rose above racism and sexism?’

One of the most amazing aspects of the Butler archive is the breadth and depth of the materials. Butler seems to have saved everything, giving glimpses of many aspects of her life, some of which are intensely personal. Her reflections on herself, her community, and her world are achingly insightful. The archive illustrates a portion of Butler’s eclectic and perhaps frenetic genius, and allows us to begin to piece together the various interests and influences that she synthesized in her writing. Butler struggled as well—with finances, with health, with writer’s block—but these human frailties informed her work, just as the world around Butler informed her work. They are some of the qualities that make Butler’s work so relatable, even [at its most] fantastic: the ordinary meeting the extraordinary. Butler became a godmother of Afrofuturism; she inspired underrepresented authors, artists, and dreamers interested in projecting a better future to have a voice in that visioning process. Her archive reveals her inspirations, her perspirations, her fears, and her private dreams … and invites us as human beings to strive for our best selves and [our best] vision the future together.